q&a

Adam Green Will Never Grow Up

In the early aughts, en route to an Albert Hammond Jr. show, Macaulay Culkin, Drew Barrymore, and Seth Green shared an elevator to the top floor of the Hard Rock Cafe in Hollywood. Alongside them stood a lanky man with shaggy brown hair and big, opossum-like eyes. The elevator stopped. Two teenage girls boarded.

“ADAM GREEN!” they screamed, snubbing the name-brand celebrities looming just inches away. The elevator collectively laughed. The shaggy-haired man smiled. He turned to Culkin: “I’m Adam Green from the Moldy Peaches.”

Green’s band, the Moldy Peaches, is his claim to fame. As champions of the East Village’s anti-folk movement in the 1980s, their charm didn’t quite translate to the masses. A review of their opening set on tour with the Strokes described the Peaches as “torturing us with the faux naïveté of Jonathan Richman imitating Beck, but without the wit of the former or the musical inspiration of the latter.” When “Anybody Else But You” made the soundtrack of Diablo Cody‘s Juno, fans on YouTube called it “bloody awful” and “cringey,” but also “perfect.”

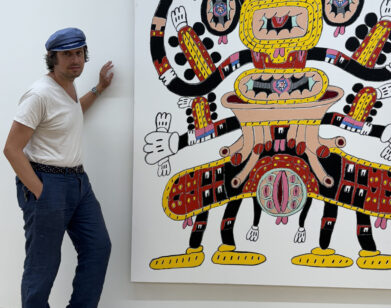

But the Peaches are only a small piece of Green’s overstuffed pie. The self-proclaimed Jewish James Dean, he is the creator of many things involving many people—two feature-length films, an art collective, an Alexander Jodorowsky-style graphic novel, an epic poem set in the Dark Ages, a series of poetry zines, an uncensored online diary, and two bounteous music careers.

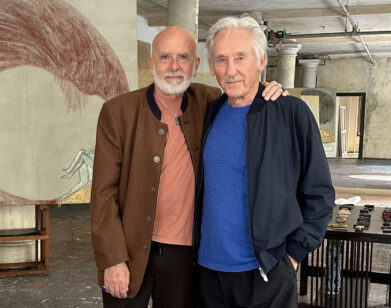

The epitome of the New York cool guy, his projects attract big name celebrities from Natasha Lyonne to Francesco Clemente, but Green maintains a modest level of fame himself. Much of his intrigue lies in that your parents wouldn’t understand his work, keeping him on the cusp of modernity.

———

MEGAN HULLANDER: You wore a Robin Hood costume on and off stage for most of your adulthood. Where’d that come from?

ADAM GREEN: In the early Moldy Peaches days, Kimya wanted to be a bunny rabbit.

In the mid 90s, a 13-year-old Green attended an open mic night in the suburbs of New York City. Aside from him, the participants were composed mostly of college-aged goths. It was here that he first crossed paths with Kimya Dawson, a poet with a raspy girlish voice, kinky curls, an assortment of lower lip piercings and a drinking problem (that has since been resolved). As a table wiper for the nearby Pizza Pizzaz, Green would eventually spend his lunch breaks visiting Dawson at the record store she worked at. They’d sit on emptied milk crates and write songs until they had enough material to record onto his four-track in his parents’ basement. This later became the Moldy Peaches.

There was a local costume shop that burned down, and she got the bunny costume from the sale after the fire. So, I was like, okay, I want to be Robin Hood. I remember playing Legend of Zelda when I was a kid, enjoying the fact that the character looked a little bit like Robin Hood. I kind of conflated the idea of Robin Hood and an elf. There was a Kevin Costner Robin Hood and the Disney one, where he’s a fox. I like that even in movies he’s wearing a costume like he’s in a play. And then I just went and sewed my own little hat and stuff. Over the years, a lot of people thought it was Peter Pan. But I knew it was Robin Hood.

“He’s a kid in a man’s body,” his dear friend and frequent bandmate, Ryder the Eagle says. Perhaps that’s why Green’s signature look is often confused for Peter Pan’s. Adam Green will never grow up.

HULLANDER: Has fashion always been big for you? Because you have the Robin Hood look, but you also costume your films in a very distinctive way.

GREEN: When I started to make movies, I imagined this world called Regular Town. The residents of Regular Town all wore high-waisted bell bottoms and frilly shirts. It’s very Renaissance. It was just sort of a way to separate that from the world that was happening every day. Of course, I was willing for the real world to become more like Regular Town.

Adam Green’s Aladdin is a materialist fairy tale built around the evils of technology, repressive government, and greed driven by a genie who functions as a 3D printer. Aladdin brings the classic Arabian Nights tale into a distorted vision of modernity, as perceived by Green, in Regular Town. The cast appears to be wearing clothing straight from Green’s closet; he used a tailor for his personal wardrobe, as the 70s-style pants he craved were out of vogue.

HULLANDER: I heard Aladdin went $200,000 over budget.

GREEN: It was a real money pit. And it just wasn’t going through a more traditional route, being sold or circulated at film festivals and stuff. It was considered to be too strange. People were too scared to play it anywhere. I just decided, I can kind of make my own traveling show and just show the movies. I just booked my own tour of it around Europe. I did 100 concerts, and I bought a projector and played the movie. And then I played a concert for them with my band after. We were dressed like the characters in the movie.

HULLANDER: Why’d you put it up for free?

GREEN: Netflix actually rejected it. They didn’t want to put it out. And then people said I could put it behind a paywall. Ultimately, I decided that I’d rather have 200,000 people watch it than 2,000 people watch it and pay three bucks for it. So, I just put it on YouTube because we could, we owned it. And now people can watch it whenever they want. And, actually, it’s been great. I mean, the losing money part is horrible. But people watch it all the time, and that’s awesome. It has its own life.

HULLANDER: Did you just take the financial loss yourself?

GREEN: It sort of ended my film career. Last time I was able to make one was with my film collective with Macaulay Culkin for Father John Misty.

The collective, initially christened Three Men and a Baby, consists of Green, Culkin and another longtime collaborator of Green’s, the multi-disciplinary artist Toby Goodshank, who was a member of the Moldy Peaches and the iPhone cameraman for Green’s ketamine screwball tragedy The Wrong Ferarri. Visual effects wiz Thomas Bayne was later added to the group, making it Four Gods and a Baby. They put together a video for Father John Misty that features Culkin as Kurt Cobain, nailed to a cardboard cross.

We set it in Regular World, but that was because it had a pre-approved budget. I can really only work now with the pre-approved budget. I wanted to make the movie War and Paradise, which was going to be more expensive than Aladdin. So I made it into a graphic novel.

HULLANDER: And now you have an epic poem. You’ve sort of become even more obscure in your form. Was that intentional or also budgetary?

GREEN: If you want to get somebody to stop talking to you, tell them that you’re working on an epic poem. I understand that, like, it’s a very unappealing notion for people. And that’s actually why I’ve been working on making it into an epic poem movie. It’ll be fun to hopefully someday screen in a movie theater. Is it masochistic? I don’t really know why it’s going more and more obscure, a lot of it is just budgetary. I find myself relegated to smaller and smaller spaces.

HULLANDER: What’s next in terms of form then? It’s hard to go more obscure than an epic poem. I know you’ve taken an interest in perfumes.

Years ago, a few comments about how good David Bowie was rumored to have smelled thrust Green into a hero’s quest to discover his revered scent. Bowie, it turns out, most likely wore a variety of scents; perhaps he just had the nose for the good ones, or maybe they thrived with his natural musk.

GREEN: I can’t really smell anything right now. I just got a cold. But it’s almost a dimension unto itself. I had to learn it from scratch. It was almost like learning a foreign language where I didn’t even understand the customs. For example, a barbershop smell. I didn’t understand what people think barbershops smell like. I’ve ended up seeing fragrances like snow globes that carry information as a landscape. I do believe there’s a lot of encoded information in them.

HULLANDER: What’s interesting about scents for you now?

GREEN: It’s almost that people aren’t even really willing to smell the way that they used to be willing to smell. The smells I smell now at Duty Free, the newer smells, almost smell like digital musks. They smell of copy machine toner. People smell like a file type. It’s just the way different people aspire to smell. I tried to write a script about it.