LIT

Wayne Koestenbaum on Poetry, Puberty, and Purgation

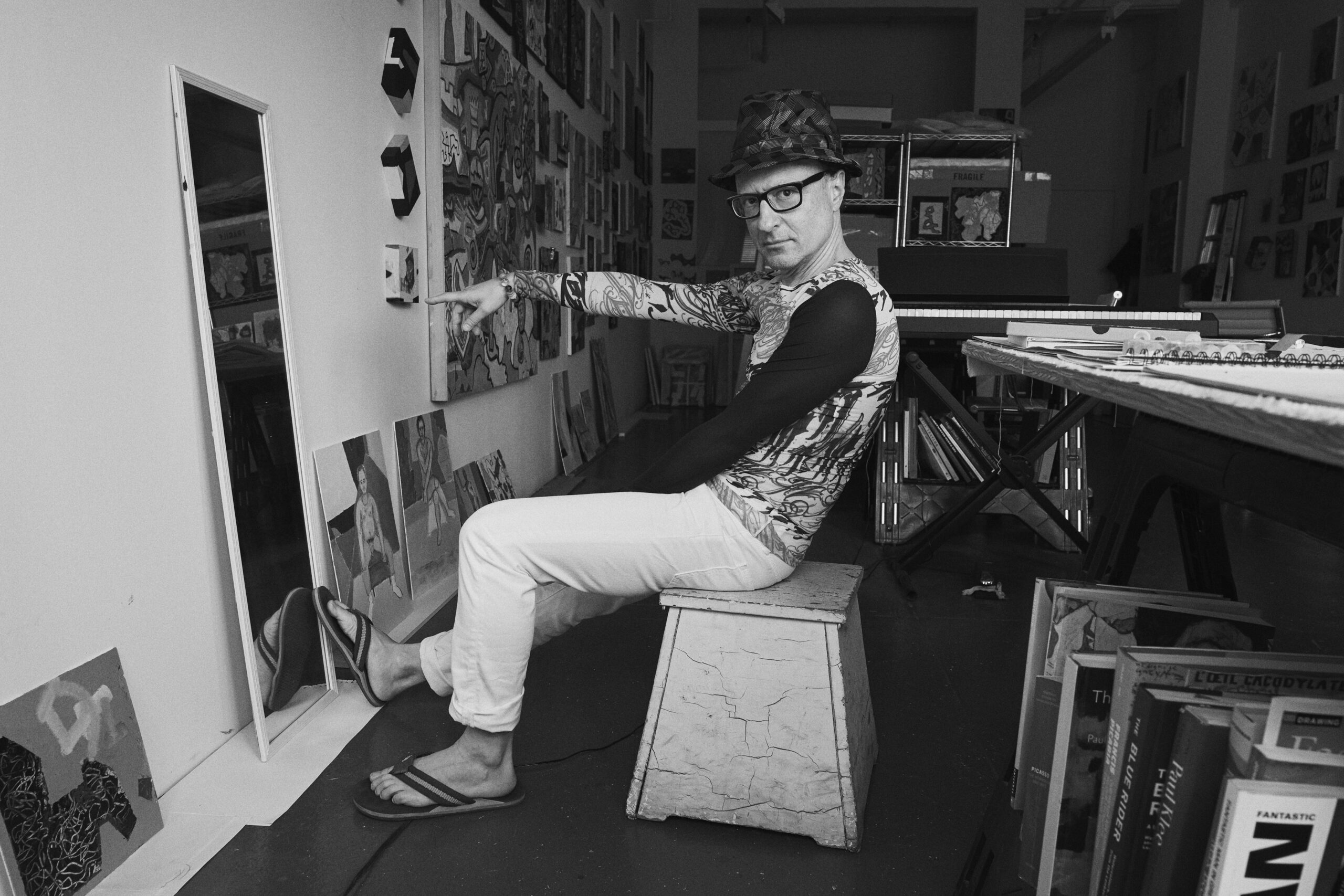

Wayne Koestenbaum is a pleasure seeker par excellence. The New York-based artist, performer, filmmaker, poet, cultural critic—and Distinguished Professor of English, French, and Comparative Literature at the City University of New York—delights in the intricacies of language, carousing across staid grammars for the most vivid and vivifying forms of engagement. A staggering repertoire of writing attests to Koestenbaum’s unbridled yen for high and low. He’s penned scholarly volumes on Andy Warhol, the erotics of male friendship, and the psychodynamics of humiliation; written lucid fiction, fables, and a libretto on Jackie O.; and authored books of poetry whose ribald titles (Best-Selling Jewish Porn Films, from 2006) only hint at the rhapsodic pleasures contained within. At the end of February, over Zoom from our respective writing desks, we spoke ahead of the publication of Koestenbaum’s latest collection of poetry, Stubble Archipelago, out from Semiotexte today. After reminiscing on our very first encounter (at the San Francisco Airport), we discussed puberty, autodidacticism, Barbara Stanwyck, and the author’s “self-scarifying diligence of procedure.”

———

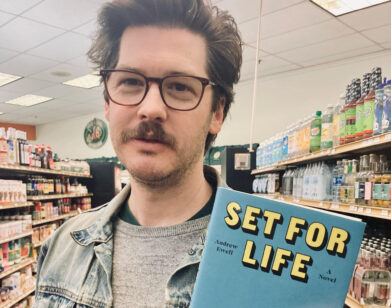

TAUSIF NOOR: I shaved before this call to discuss your new book Stubble Archipelago, partly because in your text, the process of shaving becomes an entry point to talk about so much more. I’ll divulge here that I had not just a little caterpillar mustache, but a mustache when I was about 12 years old. The hormones hit me quite early. In Stubble, for the poem that begins “O razor,” you also incorporate the phrase “Barbara Stanwyck is the Coit Tower on the hill/ of my discontent”—so there’s bit of the San Francisco Bay Area inside a book made from your flânerie around New York City. Do you remember the first time we met, a few years ago, at SFO? I came up to you and said, “You’re Wayne Koestenbaum!”

WAYNE KOESTENBAUM: At baggage claim!

NOOR: Yes, exactly—a baggage claim of many sorts. Let’s maybe start with the importance of place in your work.

KOESTENBAUM: I’m from the Bay Area, from San Jose, a fact which you know as my friend, but it also comes up in my work. Until I was a senior in high school, when I spent a summer in Aspen, I’d never been further east than Reno until I went to college, after which I essentially moved for the rest of my life to the East Coast. And because I grew up in San Jose, I had inscribed in me from the beginning a binary of the suburbs and the city, which was San Francisco. Now I can see it as a quaint, cute city and can understand its European charm, but as a kid, it was the quintessential metropolis and, because this was the ‘60s, the site of sin: gay lib, hippies, and a loosening of restrictions. San Francisco formed my horizon of desire and my developing lexicon of cultural references—it was my training as a fag, but also as a cultural critic. I always thought of myself as coming from New York City because as a kid, I had acquired my mother’s Brooklyn accent, and my Jewishness was conspicuous in a way that’s almost impossible for me to render real for other people when I talk about it. It’s loaded in the same way that the Berkeley Barb and City Lights Books became loaded signifiers. It’s been a shock to me since the beginning of my writing life to see both the faggotry and the Jewishness emerge as central—certainly before the ‘90s when gayness became capitalized in a certain way.

NOOR: There are certain queer lineages of writing and art that use place as a catalyst—the power and necessity, perhaps, of a fantasy that’s always over there, which mobilizes so much of what one notices and takes in. Reading Stubble Archipelago, I see how you’re metabolizing disparate elements, which could not have happened without all your years in New York and your attunement to environment.

KOESTENBAUM: The line from Stubble that occurs to me as I listen to your question is when, at the end of one of the sonnets, I name “Gregory Battcock washing / his ass in Riverside Park / between efficiently sandwiched tricks”—an art critic from the ‘60s, early ‘70s in New York and a minor figure reclaimed by the likes of you and me. I’m zooming in on him as a site of my future and as a site of aspiration from an elsewhere. He represents a future metropolis for me, but he was tragically murdered and dwells in the past. He symbolizes the site of arrival that I’m yearning toward. It’s a place, often in the past, that has been culturally marked and signposted and mausoleumed or epitaphed, but an inscription blurred by neglect and minorness. My task as a name dropper in these poems, and in all my work, has to do with restoring a private luster to these gravesites that I feel that only I and others similarly constituted have the power to do. My work is sometimes misread as merely erudite, perhaps because I’m an academic and that’s my job. My writing is misread as inaccessible, which implies a departure from emotions or from experience. Name dropping—and I get that practice from Frank O’Hara, among many others—is about passionate reclamation, making a loud claim, like a dog pissing to mark territory.

NOOR: It’s your Anna Moffo, your Barbara Stanwyck.

KOESTENBAUM: Exactly. My Gregory Battcock. Barbara Stanwyck doesn’t need my reclaiming, but there are always new acts of camping out under the circus tent of a new name.

NOOR: Let’s discuss the structure of Stubble Archipelago and how you arrived at it.

KOESTENBAUM: It started from a sense of fatigue and a need for mode change after finishing Ultramarine, the third book of my trance poem trilogy [alongside The Pink Trance Notebooks and Camp Marmalade]. Those were diaries written with the kind of fluency of automatic writing, but also a kind of séance, a writing receptive to buried lexicons—what Lucie Brock-Broido referred to as the “word hoard.” I was claiming my collective-unconscious word hoard through a process of unleashed writing and then carving three books out of these spelunking missions. The experience was deeply fatiguing, continually accreting a pile of more words to be shaped later. The method created a sort of vertigo and nausea. I longed for a container. I had started dictating some essays with the voice memo function on my phone as a response to a fatigue from my own verbal glut. I walked around New York while dictating and when I got home, I’d transcribe my dictations. I decided that these recitations should assemble into something sonnet-like without being sonnets. I created a form based on the first poem in the book, depositing the day’s leavings without demanding segue or homogenization between different elements. Each poem does not represent just a day. Sometimes two weeks can happen within a cabinet of 14 lines; these poems, gathered together, form a consecutive diary. Each line can spill over, and it can have indented little tributaries. It struck me when I started writing these poems that I didn’t sound like me any longer. That’s what I wanted. Halfway through, the book’s voice starts to sound like me again, but at the beginning it doesn’t sound like me, and that’s an incredible liberation.

NOOR: You mentioned your poems having little tributaries, and we might think of poetry—now this is Bernadette Mayer quoting John Ashbery—as a stream that you can always dip into. And John Stuart Mill once wrote that eloquence is heard, but poetry is overhead; you’re always listening from the other room. This name dropping I just did, as you mentioned, becomes quite personal, so reading Stubble, I’ve been thinking about a personal historicism. You’ve written, for instance, about the thrills of fandom, and what emerges from the perspective of the fan: that too, is always aspirational and lodged in fantasy. The peripatetic quality of Stubble really adds to this sense of finding your own fantasy.

KOESTENBAUM: The working title for the volume was “Peripatetic Sonnets,” and then for quite a long time, it was called “How Men Eat.” But rather than the slaughterhouse sublime, I wanted something lighter, so then it was called “Pansies, Please,” which I liked because it reminded me of Eileen Myles’s Sorry, Tree. I like the notion that I, too, am a nature poet. Then, the book was called “The Language Glove,” which I liked because it alluded to fisting, and because there’s a line in the book where I say, “Everything can fit in the language glove,” which is the carapace of the sonnet where anything could go. Language is the glove into which I stick my hand, which permits me contact with the world. The book ultimately became Stubble Archipelago. I don’t know why I’m telling you the different titles, but it’s fun to do. Stubble Archipelago returned me to stubble, which seemed as permanent and locating as anything I could claim in my whole writing life. But with regard to a personal historicism, one example I can think of is in the fifth sonnet, where I mentioned Jo Van Fleet.

NOOR: Yes, let’s do a close reading of that section of the poem:

Sticky juice, my habitat pudding, sti-

chomythia tinkling also—

Lady Anne + hunchback,

discontented winter’d him tramezzini, like sandwich-

ableism Jo Van Fleet

Abel-Mom kissing Cain.

KOESTENBAUM: There are a lot of puns, and it’s really compressed, but believe it or not, I know every step of logic and it’s actually legible: tongue juice, semen, sticky juice, moving into habitat, which is location and the way we make a habitat out of zero. Moving orally as mélange through stichomythia, a Greek poetic device about doubling, going to stichomythia in Shakespeare’s Richard III, but with tinkling and urination, which gets us back to all the things that matter in this book. Lady Anne and the hunchback: hunchback is Richard III and so then we get disability, and discontent—“winter of my discontent” is the first line of Richard III. Tramezzini is a kind of sandwich with the crust cut off, which has to do with the middle, sandwiched between ableism and Jo Van Fleet—like Fleet enema. Jo Van Fleet plays the mother in the East of Eden film adaptation with James Dean. Then there’s the historicism in the dialogic form of Greek comedy or tragedy, stichomythia, through the disabled outsiderness of Richard III, and all the traits of the other that Shakespeare is summoning by creating the myth of Richard III being a hunchback—in fact he merely had a curvature of the spine. In my work, I’m often talking about my own method, so the book is self-referential, but it’s also an avenue for the reader to understand how to find nooks for making a habitat from daily detritus and cultural refuse. But that avenue goes through the Fleet enema of Jo Van Fleet. That too is a personal historicism—my Jo Van Fleet comes from the Frank O’Hara seat of James Dean idolatry. But I’m not Frank O’Hara, and I’m not in the ‘50s, so James Dean isn’t quite right. I’m impersonating an upward glance toward James Dean that, for me, is actually a retro glance.

NOOR: Which is to say that the interpretation of your poetry can always be routed through ventriloquization and adulation. You know, all of us are always writing in the shadow of death. Lyn Hejinian passed away the other night, and I was re-reading her powerful essay on the closure of form. She writes that form is “not a fixture but an activity.” How do you relate to that, as someone who works across poetry, essays, painting, performance and music, and now film?

KOESTENBAUM: I often call it self-sickness, disgust toward the self I see. There’s no self-pathologizing in this stance in the least. I’m not a special case and I’m not minoritizing my shame by saying that I have an excess of self-disgust. I look to the writers I care about, like Elfriede Jelinek or Dodie Bellamy, and in their works I locate a flowing production of text that is constant, masturbatory, purgative, and occasionally induces displeasure in the maker. It’s both the surplus of the making and its scatological or erotic nature that produces disgust, and that disgust produces a wish to flee. For me, that flight takes place through other genres and media. I often phrase this detour into other media and genres as coming from a sense of claustrophobia. It’s only now talking to you that I realize it’s a deeper affect than claustrophobia within, say, the critical essay, that makes me fly to fiction. My haptic sight sees my own productions with a palpitating sense of their grotesqueness. To escape from that shame, I need to move to another form, and the other form always represents a return. I’m fleeing into these containments, but I’m going back. The first poetry manuscript I ever put together was a book of sonnets, which never got published. And my flight into filmmaking puts myself right back in San Francisco with my Super 8 camera in the 1960s. I’m finishing a movie right now, which is basically, like many of my films, a portrait of a beautiful man.

NOOR: Once you return, you’re also always changed, like Odysseus. You’re not the same self, and the reason I value eclecticism is because it’s inherently an education that leads to the discovery of other selves, or perhaps layers of the self. I want to ask you, as I always ask writers I admire, about your relationship to your education.

KOESTENBAUM: I’m remembering the first English paper I wrote in college, for a course on modernism. One of the possible topics was to do a close reading of Yeats’s poem “Byzantium.” I didn’t know how to start, so I wrote out the poem, and I left a lot of space around it, and I made a map, mostly of all the sound relations of the poem. I chose the path of painstaking autodidacticism. Although I was in a class to give me the cultural authority of somebody who knows about modernism, I was taking a devious, and in a way clueless, route—refusing the bigger picture, refusing to make connections between different bodies of work, refusing history—all to dive into the surface and sounds of one poem. In effect, I was putting myself through a lot more work than if I had chosen a topic that involved a little research rather than this haptic clawing in the dark.

NOOR: You took the performative route! Tell me about the performance you did recently at Francis Kite Club.

KOESTENBAUM: I’d spent the last month in my own conservatory training camp putting myself through an ordeal of preparation. When I decided to do this piano performance, I was initially going just to improvise. Instead, I returned to Bach, who was my favorite composer when I was growing up. I Xeroxed the score of a movement from one of his English suites, and I took a poem of mine called “Passé Ass,” and fit each word to each of Bach’s notes so I would intone the poem during the performance. I’m desiring the passé, desiring to penetrate and sodomitically claim the past. Or it’s my own ass that’s passé. My practice of slowing down time to pile poem and music together in a way that they don’t belong, putting myself through an inner conservatoire to embody a union of words and music that’s actually impossible, is quixotically self-punishing. It’s a chosen masochism which involves rigorous procedures that might not pay off, but that offer a necessary purgation, a microscopic zooming in on detail, and a refusal of context. It’s a self-scarifying diligence of procedure, which is for me, the only method I know. The way I write is not by thinking, but by moving word by word. I’ve never been able to write by thinking. I work through the words I use and tunnel into them. I have a rage to establish a procedure that I can follow.

NOOR: In many ways, what you’ve been talking about is a rigidity that breaks open new forms of understanding. As James Joyce said of Beckett’s work: it is not about something, it is that something. On the one hand, the reader is engaged in an associative decoding, as we did earlier, and on other hand, it’s the pleasure of the movement itself, musicality and the flow of sibilance and assonance. When you were talking about the masturbatory earlier, a phrase from the book came back to me: “onanism con ragù.” I could try to figure out what it means, or I could revel in the flow of onanism con ragù. So flow keeps coming back to us, from dictation to text to reading to live performance.

KOESTENBAUM: That’s why I—that’s why we—love writers and artists. It’s not that we we totally succumb to the genius myth; we succumb a little bit. I, and we, love exemplary lives, lives crammed with flow and with product and with that cream of making. When we began talking, you said that you’d had a mustache when you were 12. I envy that because I had a somewhat late puberty. I’ve said many times in my work I thought that puberty would literally never happen. I’m not sure it ever did, in a funny way. As a dream vision, in a sense, for me, puberty remains in the future. I gaze with a future I: I’m not looking back at puberty as a writer-thinker-maker, I’m looking forward to it. I lay claim to this position of standing puzzled at the gate. And I remain, stubbornly and rigorously poised there, because I find it educating. It’s a handy, ornate, staunch, maladroit, and secretly stimulating position from which to inquire.