DIRECTOR

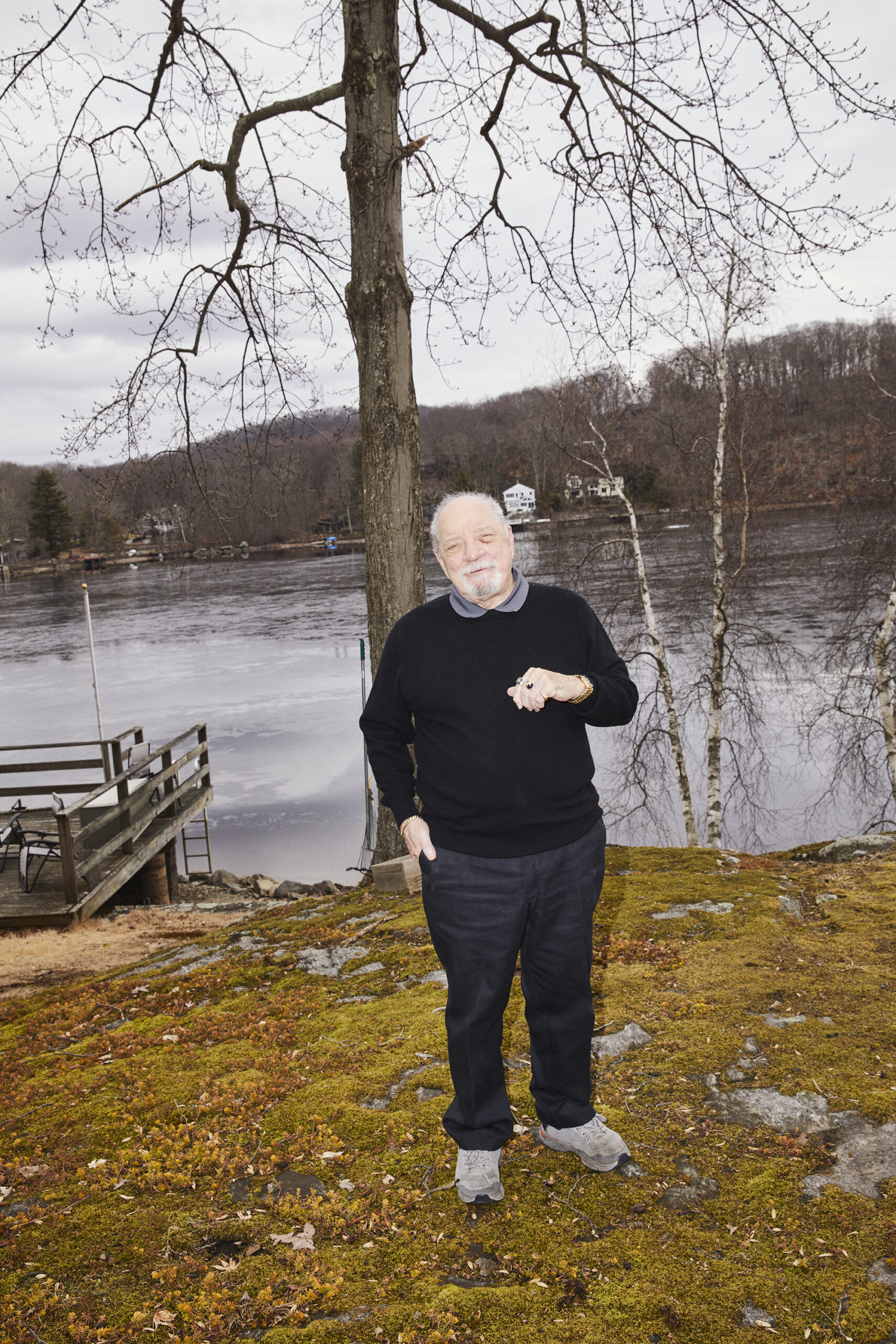

Paul Schrader Takes Oscar Isaac to Movie Heaven

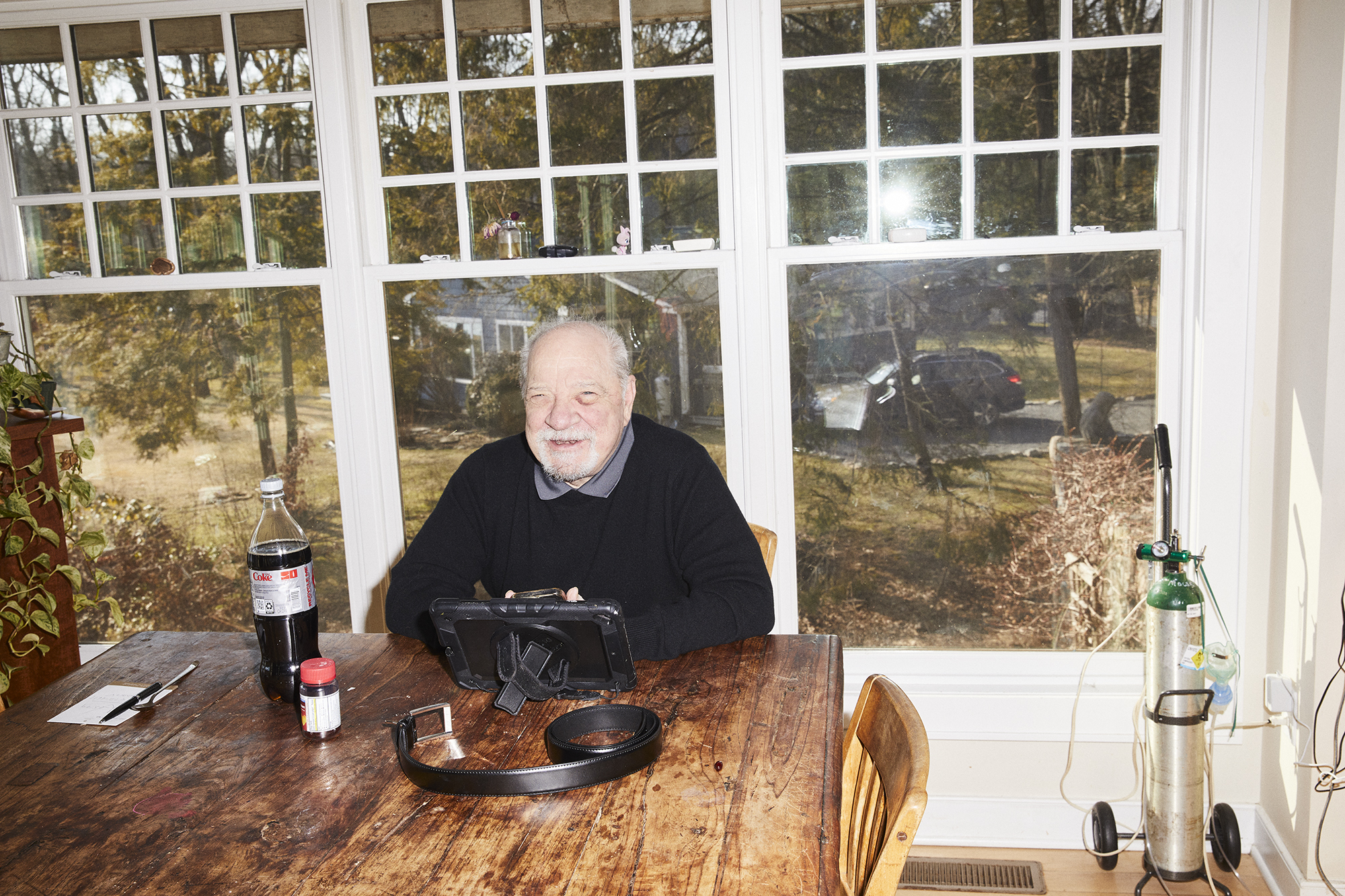

Paul Schrader was in his new apartment in Manhattan, having just left upstate New York to return to the borough he so hellishly rendered in Martin Scorsese’s 1985 classic Taxi Driver. Joining the writer and director of movies like American Gigolo and Cat People was Oscar Isaac, who starred in his 2021 revenge thriller The Card Counter. They were meant to talk about Master Gardener, Schrader’s latest rumination on tortured men, but Isaac had been so busy with his BAM run of The Sign in Sidney Brustein’s Window that he didn’t have time to watch it, so they talked about the past, present, and future of movies instead.

———

MONDAY 12:30 PM MARCH 13, 2023 NYC

OSCAR ISAAC: Hello, Paul.

PAUL SCHRADER: Hey there. How are you?

ISAAC: Good, man. Just running around.

SCHRADER: You look tired.

ISAAC: Yep, that’s me. My one day off a week.

SCHRADER: Thank you for doing this.

ISAAC: Of course. First question, what do you do when an actor is late to set?

SCHRADER: I’ve been very fortunate recently, because I work on tighter budgets, and everyone knows that one late person hurts everybody. And also, I believe actors are better behaved now than they were when budgets were bigger and schedules were longer. With the new technology, actors don’t get much trailer time. They used to get three or four hours a day of doing nothing. Now, some actors on my films are on set all day. It’s not a problem for me, and it’s less of a problem in general, unless they’re one of the companies that has so much money that no one cares.

ISAAC: Yeah. That was my experience on your set. I don’t think I was ever in the trailer. We’d do two, three takes max. Obviously, if there was a problem we’d go longer, but generally we were moving. I remember feeling it was such a wild combination of first-time filmmaker energy with a master knowing exactly where he wanted everything to be. Do you think if you had a bigger budget, you would allow yourself to do more takes?

SCHRADER: That’s an interesting question, because I’ve grown to not like doing so many takes. When I began, you would do five to six takes. Now, I’m down to three to four, sometimes two. Years ago, when I did a film with George C. Scott, I met with him beforehand, and he said, “I’ll give you two takes. The second one is going to be exactly like the first, but if you want a third take, you have to give me a reason for it.” And it was true.

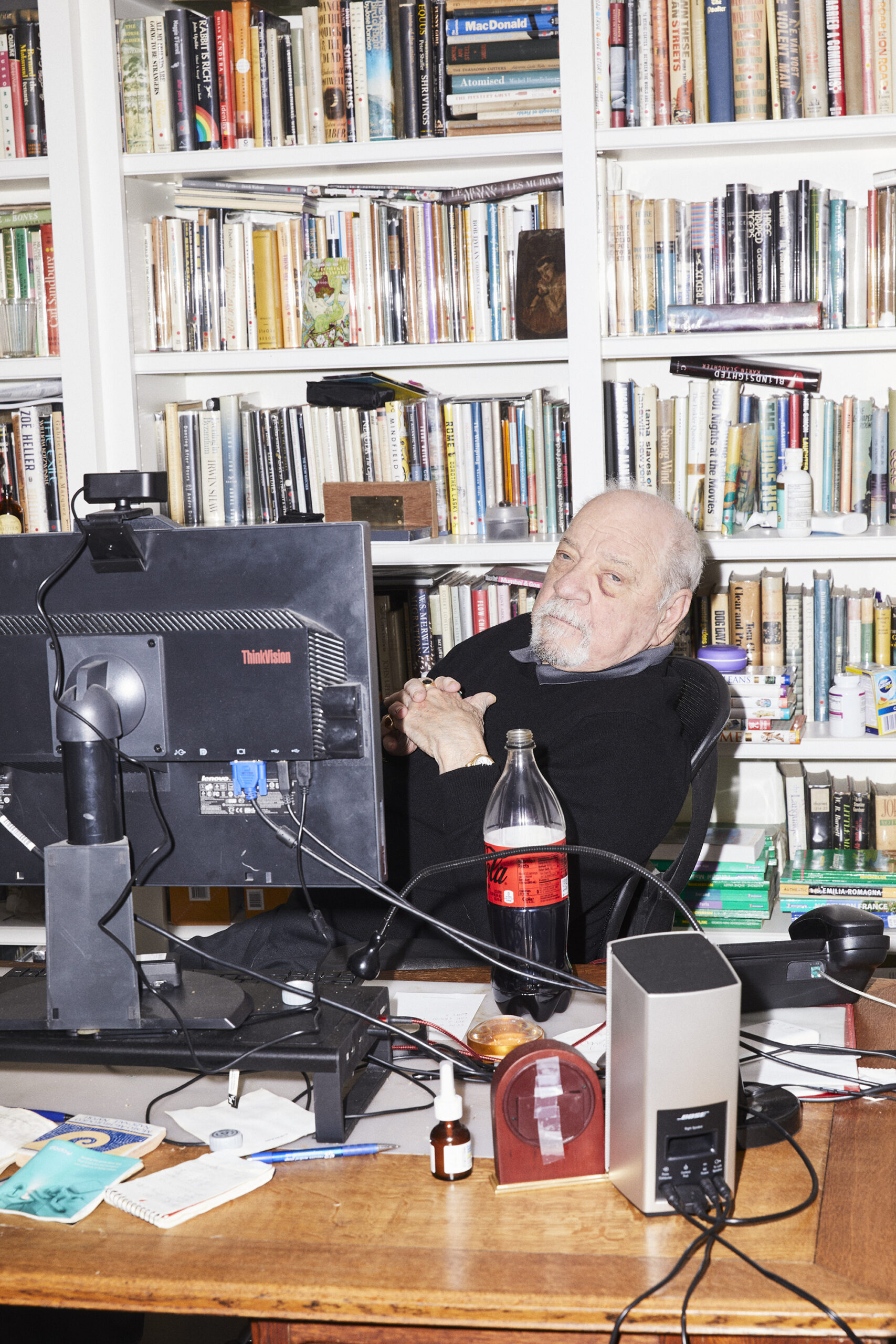

ISAAC: Interesting. Now, let me ask, do you have a very specific place you like to write?

SCHRADER: Well, there’s certain things you need. I’ve just moved back to Manhattan, and I like my space here. It takes a number of days to lock into a place. Usually, you spend a day just acclimating to a space before you can really start writing there. Different writers have different, what they call “the regimen of the room,” all these rules. Don’t ever go into the writing room, unless you are planning to write. Don’t go in there and do anything else. For some writers, it’s 500 words a day, no matter what. I’ve been in various writers’ rooms—Faulkner, Steinbeck, and Mishima. Mishima had an upstairs room, and he had a locked door. You unlock that door, and you go down another hallway, which was all dark, to another locked door. So he would lock both doors, and then he would be inside his room. The only thing he could do there was write. His nickname in gay circles was Cinderella, because no matter what he was doing, or what kind of sexual episode was going on, he’d check his watch, and he had to be home at midnight to write.

ISAAC: Do you feel that the script is its own piece of art, or is it really just a blueprint so that you can get the movie done?

SCHRADER: It’s a blueprint. Depending on whether you’re writing it for yourself or someone else, it’s a different type of blueprint. That’s why I ended up directing in the first place. I had been a nonfiction writer, and I thought, “You’re either going to be a writer or a filmmaker.” There’s this thing called a screenwriter that’s somewhere in between. They’re not putting your words up onscreen, they’re not publishing them. And once I started becoming a filmmaker, the idea of being a writer for others didn’t seem so diminishing as it did before. There’s been a whole history of Hollywood novel writers who have whored in the valley of commercial cinema, like John Gregory Dunne, or Gore Vidal, or F. Scott Fitzgerald. Anyway, they tend to say one is better than the other.

ISAAC: That’s interesting. My father was visiting and, as is his way, was undercutting what I do by talking about how he’s lost interest in fiction to a certain extent, because it feels like it’s an imitation of the real thing. It’s an interesting idea, because obviously storytelling is so integral to human nature, and I told him, “Christ spoke in parables.” Those were fictions, but he was trying to make a broader point.

SCHRADER: Part of the irony of this whole reality TV movement is that reality shows are more fictional than the fictional shows.

ISAAC: Right.

SCHRADER: So even if your father is looking at this reality show, he’s just being bamboozled.

ISAAC: Do you revisit your old work much?

SCHRADER: Not really. I think that’s a very slippery slope. Everything changes, and there’s nothing you can do about it. When people like George [Lucas] work with CGI, you’re not going to recast the movie, you’re not going to rewrite the movie. You could fool with the color. I think Terrence Malick fooling with the color was wrong, and I think when Francis [Ford Coppola] did his longer version of Apocalypse Now, it was worse than before. So I think it’s better to just let them be.

ISAAC: Mm-hmm. Whose opinion on your work matters to you, if any at all?

SCHRADER: That’s kind of rough, because if it works for me, I think it really works. I’m appreciative of others, but people say some of my films are better than I think they are. Hardcore is one that lately has been getting an increasing reputation. I’m happy to have people say it’s good, but I don’t necessarily agree with them. I did this film with Bret Easton Ellis called The Canyons, which was a cool little B movie, and it got attacked for all kinds of extracurricular reasons, mainly for starring Lindsay Lohan and James Deen. I never took those attacks seriously, because they weren’t right. Eric Kohn is one of the editors at Indiewire, and the first time I met him, I said, “Eric, you really fucked up your review of The Canyons.” And he said, “How’s that?” I said, “You did something that is a great temptation to reviewers. You reviewed the phenomenon. You didn’t review the film.” And he said, “Okay. I’d be willing to see it again with you.” I said, “No, I have a better idea. Let’s go to lunch.” And now we’re friends.

ISAAC: [Laughs] It’s the day after the Oscars. How do you feel about awards and their relevance?

SCHRADER: It’s hard not to feel good when people say nice things, even when you think they’re wrong. On the other hand, I remember saying to Scorsese years ago—because Marty had a very strong desire to win an Oscar, and should have won an Oscar for some of his films, but didn’t, and he was chafing—so I said to him, “Marty, if your priority is to win an Oscar, you’re going to need a new set of priorities.” And fortunately he did win his, but all you have to do is look back through the litany of films that have won to realize that it’s not company you really want to be in.

ISAAC: Is it something that you’re still going to be involved in?

SCHRADER: I haven’t watched it in 10 or 15 years. I still voted, although this time I think I abstained in 80 percent of the votes.

ISAAC: [Laughs] You are a Calvinist, right?

SCHRADER: [Laughs] If I looked at five names, and said, “I’m not really crazy about any of these,” abstain, abstain, abstain. Because it is so much a part of the economic, raw material of our business. Variety and The Hollywood Reporter would have been long gone were it not for the dollars of Oscar advertising. And the Academy got itself in a terrible mess by building that huge museum and giving themselves a mountain of debt, so now they have to keep figuring out how to get more and more people to watch the Academy Awards in more and more countries, so they can make more and more money, when in fact, it began years ago as a local thing.

ISAAC: Something I prize so much in you, and a reason why I see you as a kindred spirit, is the desire for a bit of subversion. At the core there’s a bit of disobedience that fuels some of our artistic desires. Can you talk a little bit about that?

SCHRADER: Being a bad boy often implies vandalism of a severe nature, or jail, or being hauled before a judge. I was raised in an environment where you could be a rebel by going to a movie. And so I still have a component in that anything worth doing is going to shake some people up, and if it’s not shaking anybody up, then maybe there’s something wrong.

ISAAC: What do you think needs to happen for theatrical to be saved, if it needs to be saved at all?

SCHRADER: Theatrical is dying. There’s only four real reasons left for it. One is the spectacle, which will only grow with larger, immersive environments; the merging of the amusement park ride with the cinema experience. That’s a reason to get out of the house. Another reason to get out of the house is a date movie, if you need to get an arm over, and so that’s why we have horror and certain kinds of comedies. And then, the third reason is that you have children, because parents just love to see their kids laughing with other kids. And so those movies are doing very, very well. The fourth thing is now what they call “club cinema,” which is what you get at [New York City] theaters like Angelika, Film Forum, and the Metrograph, where it’s essentially a club. You have membership and martinis are the new popcorn. And that’s a model that will survive. The people who say movies are in trouble are wrong. Movies aren’t in trouble. Theaters are in trouble.

ISAAC: So for you, it’s not such a big deal whether someone watches your film in a theater or on a phone?

SCHRADER: No, not so much. It is a big deal if the tastemakers watch it in a theater. It’s the whole point of setting the table for a three-week theatrical run, having film festivals, so that the spearheaders of public taste can see it in that context, and write about it in that context. Otherwise, it could disappear. So you take a film like we did, The Card Counter—now that had a short theatrical run, it had a nice festival run—and when that pops up on a streaming service, people don’t go, “Blah, blah, blah.” They go, “Oh, wait. I heard about that movie.” That’s all you need. Then they will stop and give it a shot. But you’ve been there where you see something that pops up and you never heard of it before, you have no idea what it’s about, and you just move on.

ISAAC: Yeah. Is it still tough for you to get your films made? Is it harder or easier now?

SCHRADER: It’s in fact easier, because when I began, the average shooting time was around 45 days. Now, for that same movie, it’s around 20. So that means half the expense, and more film. You’re actually getting more film in 20 days than you get in 46 because the camera’s never off. Then, you can come pretty close to guaranteeing you’re going to get your money back. That’s all I think I’m obligated to do. When I say, “You’re going to get your money back,” I mean it. I used to say this, and I didn’t mean it. I knew I was lying. Now, I think I can say it and mean it. You may not get rich, but you’re not going to lose it, and so that has allowed me to make films more easily as long as I make them within a certain context. But I have never been drawn to the big toys like George and Francis and Marty, and once you get hooked on the big toys, then the budgets go way sky-high. By big toys I mean crowd scenes, a period wardrobe, more explosions.

ISAAC: Yeah. The last thing you told me, which I thought was so great: We talked about doing a project again, and you’re like, “Just come to me with something, but I don’t do whimsy.” [Laughs] So you don’t do whimsy, Paul?

SCHRADER: No, I don’t. I never really cared much for that cutesy stuff. Jacques Tati did these films, and a lot of people love them. They are whimsy, so my definition of a room in hell would be where they only show Jacques Tati movies. And then go to the next room where they constantly play Prairie Home Companion.

ISAAC: What are they showing in heaven?

SCHRADER: I think they’re showing Michael Snow.

ISAAC: Michael Snow on an iPhone?

SCHRADER: [Laughs] Yeah. Before I wrap up, I can give you a quote. Now, you saw Master Gardener, right?

ISAAC: No, I haven’t. I’ve been doing a play, so I haven’t. Please don’t include that in the interview! [Laughs]

SCHRADER: It’s like The Card Counter or First Reformed except that it comes for the first time to a very warm ending, not a cold one. Maybe earned, maybe unearned, but it ends with a song written by S.G. Goodman, someone I’ve met who’s a songwriter from West Virginia. And we did a soul cover of her song “Space and Time,” with Devonté Hynes, and anyway, the main lyric of that song is, “I never want to leave this world without saying I love you.” And so when I was in Venice, somebody was asking me about that song, and I said, “Well, when I was a young lad, I’d say I never want to leave this world until I say fuck you. Now that I’m old, I never want to leave this world until I say I love you.”

ISAAC: [Laughs] I love you, Paul.