Faggots, Dykes, and Fairies: Welcome to the world of The Faggots & Their Friends Between Revolutions

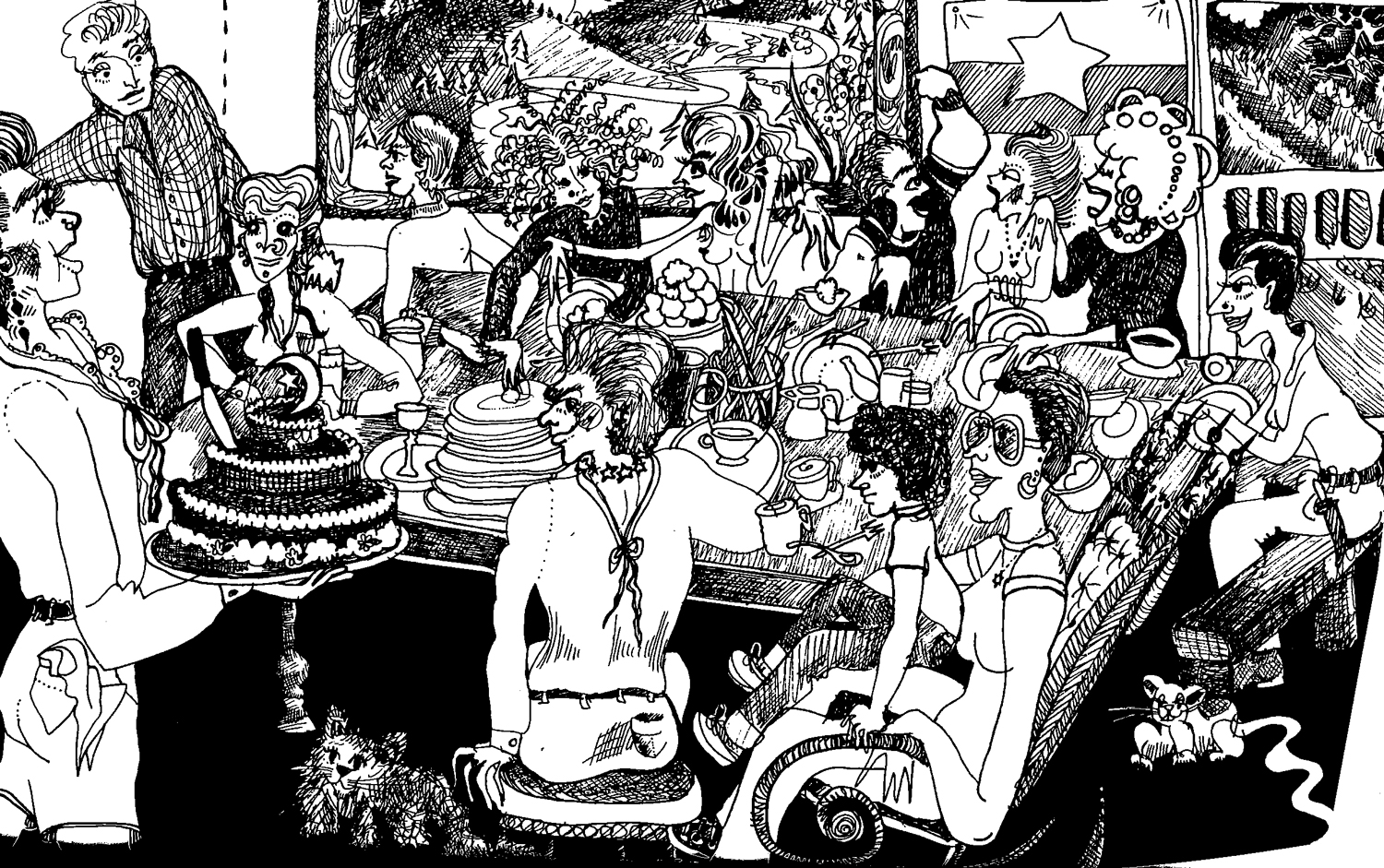

Oppression births art, hatred inspires love, and revolutions bring change. It would be easy to say that these are the main ideals Larry Mitchell had in mind when he created the astounding, dangerous, oppressive, and fantastical world of The Faggots & Their Friends Between Revolutions—but there is so much more to discover inside the book’s pages, including playful, erotic illustrations by Ned Asta. The book, originally published in 1977 through Mitchell’s small press Calamus Books, falls somewhere in between fable and “anarchist” manifesto, as Asta puts it—and it makes sense. The book was Mitchell’s response to the lack of gay literature being published at the time. The Faggots is loosely inspired by his experience living in the Lavender Hill commune in Ithaca, New York, which he helped form along with Asta. It tells the story of a brutal empire in decline, where faggots, fairies, women, and dykes aim to survive, dance, create art, and have sex under the tyrannical rule of men. 40 years later, the book has earned cult queer status, not only for its contents and valuable lessons, but for the mythology that it carries. It has been said that since it was first published in 1977, the book has been circulated and passed on from faggot to butch to fairy to dyke, in its many DIY iterations. With the 50th Anniversary of the Stonewall riots, The Faggots & Their Friends Between Revolutions is breathing new life thanks to Nightboat Books. The book includes essays from performance artist Morgan Bassichis, who adapted the book into a musical in 2017 at the New Museum, as well as a preface by activist filmmaker Tourmaline (Happy Birthday, Marsha!). In between revolutions, Bassichis, Tourmaline, and Asta (using her new iPhone) discussed the book’s mystical (and horny) nature, the resurgence of radical queer politics, and Asta’s Lavender Hill nickname, “Loose Tomato.”

———

ERNEST MACIAS: All three of you have had different interactions and experiences with the book, but let’s start with how you all met.

NED ASTA: I got a phone call from Morgan, about two years ago. They had the book and were very darling, even though they were a total stranger.

MORGAN BASSICHIS: I think you were planning some big party and making a bunch of bouquets of flowers. I remember you said to me, “I only have a few minutes. I’m making a lot of bouquets and you should know upfront, I’m a bisexual. If that’s a problem for you, tell me now.”

ASTA: Oh god! I had to get that out of the way. I didn’t want to dupe anybody.

BASSICHIS: I immediately knew I was going to love you.

MACIAS: Morgan, you reached out to Ned because you were working on a theatre adaptation of the book, correct?

BASSICHIS: At that point, I didn’t know about the history of the book and where it came from. I didn’t know we would find an amazing group of friends that the book is loosely based on called Lavender Hills. Ned was incredibly welcoming to me and to our collective, and it started this deep journey we’ve all been on of getting to know each other.

ASTA: I feel like it is a relationship.

BASSICHIS: Tourmaline and I have been friends for many years. We met in 2006.

TOURMALINE: We met through our activist anti-prison work that we both care deeply about. We have also been connected around this book. We would send passages that inspired us to each other.

MACIAS: How would you explain this book to someone who has never heard of it?

ASTA: Living with Larry and knowing Larry, he was always writing in composition books by long hand. Originally, it had all these funny names. He thought it was a kids’ book and then he showed me what you would call a script, I guess, of the book. I said, “Larry, this is not a kids’ book at all.” He said, “Yeah, I know, it’s my philosophy.” People used to call me “Loose Tomato” and they put Loose Tomato in the book.

BASSICHIS: Ned, will you say why people called you “Loose Tomato?”

ASTA: I was in my 20s and 30s. Sometimes I looked butch, but most of the time I looked femme. I would sometimes wear a loin cloth or a little tiny top or nothing. I always wore a tube top. Don’t ask why, but that name caught on. We were naked a lot. I think I’m a nudist, actually. I’m 72, and I’m still naked. I don’t know what to say about it. I live out in the country where nobody can see me. It’s very exciting. If you go on Vimeo and see Lavender Hill Love Stories, you can get an idea of what everybody looked like and what they didn’t wear.

MACIAS: Tourmaline, how do you describe the book?

TOURMALINE: I think that “72 and still naked” is a great way to describe the book.

ASTA: Oh God, really?

TOURMALINE: Speaking personally, a lot of my identity was as a movement builder, as a community organizer. Morgan and I would write each other these letters being like, “What if we were artists? Can we actually be artists?” Then we would send each other passages of the book that would help us figure out those questions. I would really describe the book as an invitation to get deeper with yourself and your truth and really shed the messages that can get so deep inside of us that keep ourselves small. To me, it’s a really profound invitation to be dependent and reliant on each other’s care, collective wisdom, and beautiful faggoty attire.

MACIAS: Morgan, how would you describe the book?

BASSICHIS: The words that I always use are part fable, part manifesto. I love how the book is about wanting everything, wanting all of our liberation in all of its dimensions, and all the pleasures in the here and now. It’s about demanding or inhabiting that freedom now in so many different iterations. It’s also about all these groups of people and different sets of chosen family inhabiting freedom in different ways. In some ways, Lavender Hill is part of that fable. It’s part of that folk tale. The book goes back and forth between these big statements almost like posters, things you’d read on a poster at a protest. I always say since my roommate Bobby gave [the book] to me when I was 20-years-old, 15 years ago, which is that it almost feels like new pages appear all the time. I’ve read it many times but it almost feels like I haven’t quite finished it.

ASTA: I still do that.

BASSICHIS: Sometimes I’ll describe it as a spell book. It’s about shedding certain genre definitions too.

ASTA: Everything you explained sounds like Larry’s philosophy, especially when you said “wanting it now, our time is now.” He always said, “Let’s not mess around. It’s now. We come out now, we do things now. It’s our time. We’re gay.”

MACIAS: What was the intent of the book back then, and does it serve a different purpose today?

ASTA: I was just thinking that way back then, when he was putting all the ideology, philosophies, and definitely anarchy into the book, even the colors being red and black, it had to be anarchistic. I’d been giving the old book out where I worked to 21 and 20 year olds. They’re so interested in it, whether they’re gay or not. It blows me away, because they’ll say, “Is this about Trump? Is this about what’s happening now?” And I think, “Oh my God, that was ’77 and we’re still fighting the same fight.” When Morgan brought it to my attention to reprint the book, I was kind of shocked. Now, it all makes sense and it’s coming full circle. The intent of the book was that we could live together, we could fight the establishment, we could make new things, and we could create a new world. I think people still want to do that.

TOURMALINE: I think that we’re in the midst of an uptick in violence against our communities. Every year, the National Coalition of Anti-Violence Projects reports that the increase in hate violence, particularly homicide and murder of trans people of color, is on the rise. We’re seeing that at the same time as really intense climate collapse. We can’t change policies, institutions, or politics without thinking and feeling differently; we can’t reorder our value systems without having a shift in what we value. Every time I read this book, I see something different. It’s about really allowing yourself to understand how you already are dependent on so many other people and in order to exist in the world—we’re all dependent. Some of us know it more deeply than others.

BASSICHIS: I’m just basking in what both of you just shared. I think it’s really important to say that this book has never stopped having a life. It’s not as if this book had a life in 1977 and then now it’s having a life again in 2019, but it has been circulated and passed between people every year since it was published by Larry in ’77, and it has been circulated by people giving each other their copies. In fact, that is the first mythology I heard about the book. You get your friends together, you get wine, and you pass around the book. People have Xeroxed copies, people have put copies online, people have DIY reprints. This book never went away. I think that signals a kind of hunger that so many of us have for a revolutionary queer politics. This tradition of revolutionary queer and trans politics has never gone away, and I think, right now, we’re in a really exciting moment—a kind of resurgence of this radical trans and queer politics that so many of us, young and old, are saying means the end of white supremacy. We are all looking for nourishment that is not fake optimism, but is nourishment to care for one another and to build the world that we all long for and deserve. I think this book is part of that nourishment.

MACIAS: It surprises me that something that was written so long ago still feels so, like you said, necessary. The book was published in an effort to have more queer art or queer writing. We live in a time now where people can create their own art and self-publish. But back then, it was a real effort, and now we have–I don’t want to say an abundance–but we have much more to consume.

BASSICHIS: The context of this book was radical print culture. This need to communicate with one another, find each other, and to create a liberationist language that includes both suffering and joy and includes both resistance and mourning. Larry talked in one of his interviews about how no one would publish queer work. Of course, we also want to remember how gender, class, and race played in, and who, even then, had more easy access to getting things printed and continues to now. But I think this sort of hunger, this hunger to print things and to create language is still important.

ASTA: When nobody would publish his work, we were in Ithaca and he was like, “I’m going to do it myself. Forget it.” I think that was a sign of the times. Whereas now, I think it would be easier and there’d be people who would publish it. I remember going to the Oscar Wilde bookstore in the West Village, he was thrilled and signing books, but that was the first book. But it was like a flirtation of what he said, “I’m not going to wait for anybody to do it”.

MACIAS: You said this book never stopped living, but it’s being reintroduced to a very intelligent and savvy generation of young, queer kids. What is the hope, that they get from this book?

ASTA: When we did this event at the Brooklyn Museum, I was signing books, and there were so many young people. It was one of the most exciting moments of my life. They were so young and just so enthusiastic about it. They said, “I love it. I love this. I love that about it. I love the philosophy.” They’re getting something, and they’re telling me that they’re getting something.

TOURMALINE: I think we’re living in a moment of deep repression and I think that people are hungry for something that speaks outside of that, and The Faggots & Their Friends Between Revolutions, from the title to the illustrations to the text in the book, it jumps out at you. In the moment of intensely policed normative culture, who isn’t going to want to read The Faggots and Their Friends Between Revolutions?

ASTA: It was fun, I was really aware of nose piercings and hoop earrings and dykes looking like dykes and fairies looking like fairies. I enjoyed it, but there’s a serious side too.

MACIAS: I’m curious, Tourmaline, as you’re flipping through it, what are you landing on?

TOURMALINE: It’s so hot. The sluttiness is so hot. I’m on page 57 and there’s this person naked on top of grapes. The gardens, the watermelon patches, and people masturbating—I’m just like, “Yes, please. More.”

BASCHIS: It comes back to what you said of “72 and nude.” The past is not over, and the future is here. Our struggles, our movements, our committees are intergenerational. So much of Tourmaline’s work has taught me this. We are our living histories and we are also ancestors for future generations now. I think what I hope people will get from this book, and what I think people are already getting, is a sense of limitless possibilities that didn’t begin with us and won’t end with us.

ASTA: Be here now, but there is a history.