Germaine Richier’s Forest

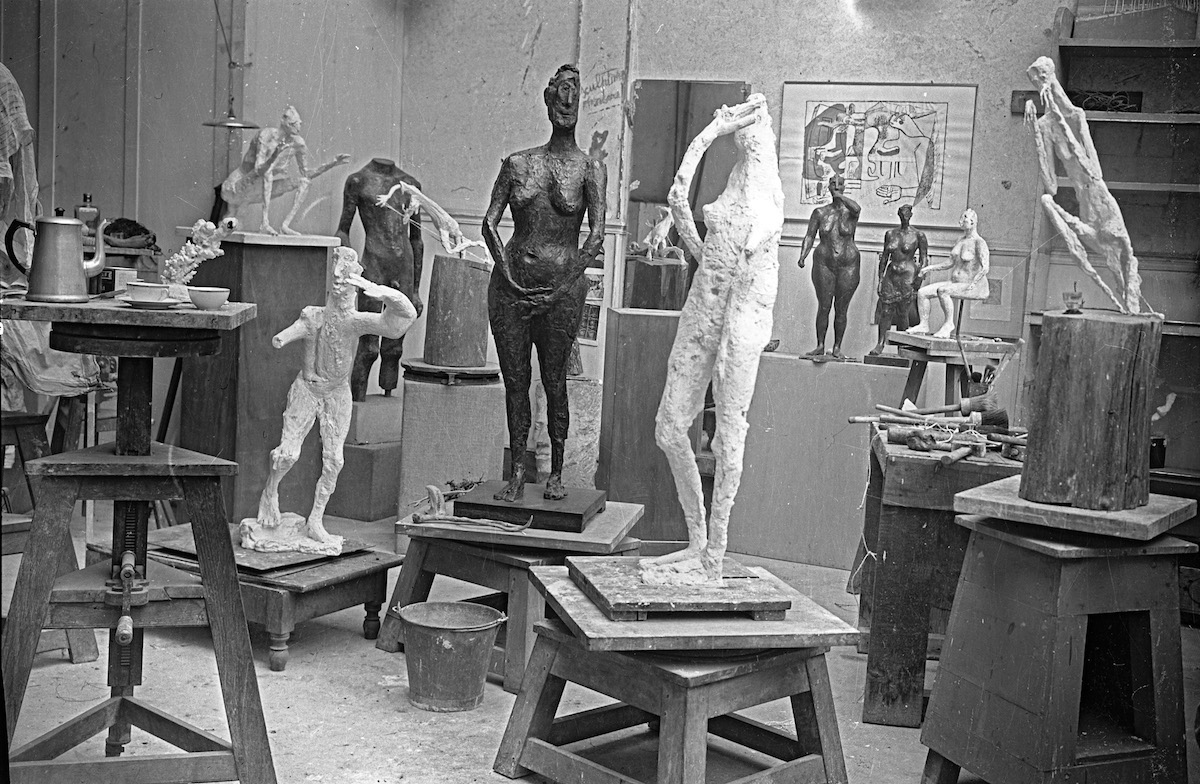

To walk into a room filled with the sculptures of Germaine Richier is to enter a mythic, uncanny forest. Creatures, some humanlike, others animalistic, stretch twiggy limbs into space; bronze skin, like bark, crackles with texture. A photograph of Richier in her studio, surrounded by a thick crop of her creations, shows her gazing at them like in a lucid dream. It looks as if they could at once snap to life.

Currently holding the artist’s works, floors of Dominique Lévy Gallery and Galerie Perrotin at 909 Madison emulate the image—though the backdrop is clean and well-lit, intended for an art audience accustomed to starker curating choices. “The installation could be surprising to many of you, because it is so dense,” said Levy, addressing the crowd at yesterday’s preview. The pieces, she explains, are meant to “echo and bounce” off one another. “If you look at the photographs of her in the studio, she was working in relation to her own work,” added the gallerist. “We tried to recreate that atmosphere.”

Within Richier’s universe lies a major, often overlooked contribution to postwar sculpture. Rising to prominence in 1930s and ’40s France, she followed the enduring legacy of August Rodin’s monumental bronzes, pioneering a surreal aesthetic that was like nothing else. She took abstraction a measure further, so while her figures ache with a human quality, they might give a classical Greek sculptor nausea. In Don Quichotte (1950-1951), for instance, arms and legs of a male statue holding a spear manifest as metal wisps stemming from an emaciated torso.

Classically trained and a contemporary of Alberto Giacometti, her status as a woman in a profession viewed as rigidly masculine saw her marginalized. This was in spite of, or maybe partially due to the fact Richier was adamently unfeminine: “She wore men’s clothes and had a manly voice,” explains Levy. “[But] I think she fought for womanhood in her sculptures, and she fought for nature.”

At the heart of her works is an organic underpinning, said to be roused by the Provence region of France, where she grew up. “She would always use some sort of natural model as her inspiration, and see where she can take it from there,” says curator and art historian Anna Swinbourne. “In every single one of the works there is something that you recognize, something that you know, something that you feel, and then, from that, we get the true essence of her vision, and her creativity.” A 1935 visit to Pompeii was also influential–a “fundamental shock,” according to art historian Sarah Wilson–that arose in her an intense existential anxiety, on top of postwar hopelessness.

“She was able to produce these extraordinary sculptures which remain about the human,” says Levy. “It illustrates to me deep loneliness, deep fear, but deep love.”

“GERMAINE RICHIER” WILL BE ON VIEW AT DOMINIQUE LEVY GALLERY AND GALERIE PERROTIN THROUGH APRIL 12.