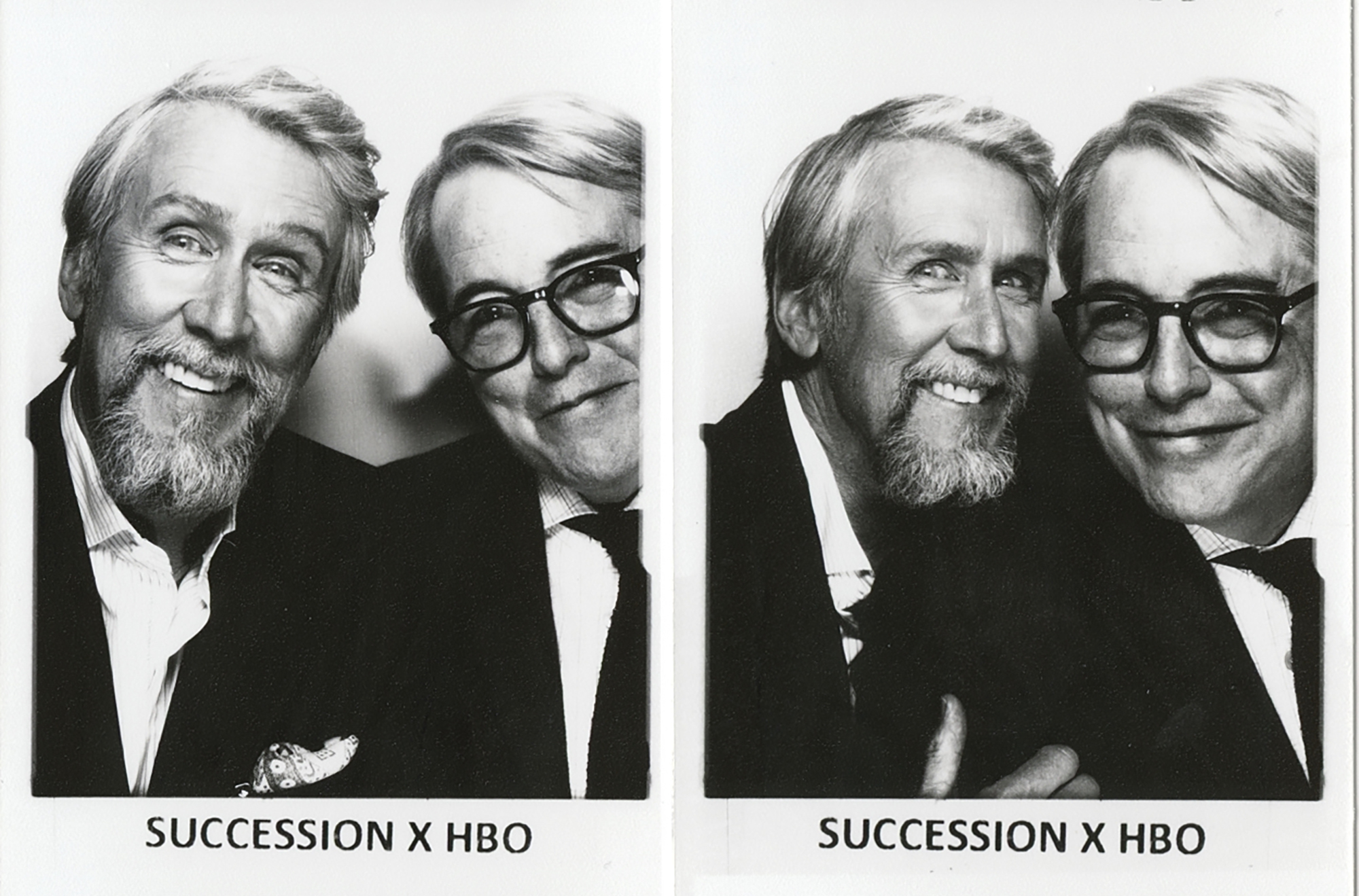

IN CONVERSATION

Alan Ruck and Matthew Broderick on Succession, Show Biz, and Ferris Bueller

Alan Ruck logs onto Zoom wearing a bowler hat and a 17th-century Venetian plague doctor mask with a beak so large it could puncture the computer screen. It’s the sort of bizarro collectible his character on Succession might own; Connor, the oldest of the Roy siblings, did after all once try to buy Napoleon’s severed penis. Ruck and his longtime friend and Ferris Bueller costar Matthew Broderick had agreed to adorn themselves in goofy headwear for their interview, though the costumes bely the absolute seriousness with which they take their craft. Both have been working steadily in film, television, and theater for nearly 40 years, and Ruck’s alternately brilliant and piteous turn in Succession as the neglected eldest son of the media tycoon Logan Roy has provided him something of a late-career surge. On Zoom, he and Broderick, who’s soon set to appear a different hit TV show, Only Murders in the Building, talked about their enduring friendship and career highlights before conceiving of a part for Broderick in Succession as a handsome and spectacularly well-endowed political fixer.

———

MATTHEW BRODERICK: Oh my god. Hello? Where’d you get that freaking thing?

ALAN RUCK: In Venice!

BRODERICK: Of course. That makes perfect sense.

RUCK: I think I should get a nose job and get a bigger nose. I think I should have a nose extension.

BRODERICK: Why don’t you wear that for a while to get used to it before you do anything so dramatic as surgery?

RUCK: I don’t know. I’m running out of time, Matt. I’m well into my 60s now. I’m looking at 70. It’s coming around.

BRODERICK: Okay. All right, so just get the nose job.

RUCK: All right, Matthew. I was obviously really pleasantly surprised to see you at the premiere the other day, and I’m assuming that J. Smith-Cameron just called you up and said, “Do you want to go to this thing?”

BRODERICK: Yes, I think that’s what happened. I’ve known J. forever because of Kenny [Lonergan]. We’ve been friends for about 45, 46 years. And I’ve known you for… how long have we known each other?

RUCK: I met you in the fall of 1980. No, in the summer of 1984.

BRODERICK: I can’t do that math, but…

RUCK: That’s almost 40.

BRODERICK: Yeah, because it’s about to be 2024.

RUCK: You know what? I’m not blowing smoke up your ass, but I owe you a lot.

BRODERICK: Why do you owe me anything?

RUCK: Because if there was no Matthew Broderick, there probably wouldn’t have been a Biloxi Blues, and that was a major springboard for me. If it wasn’t for Biloxi Blues, Ferris Bueller wouldn’t have happened for me. I’ve told you this before, but I think in a previous life you saved me from some horrible death.

BRODERICK: That’s interesting. Well, you’re welcome. But you bagged Biloxi Blues purely on your own, as I didn’t know you at all. I remember the first rehearsals, I was like, “Who’s that guy? He’s so good.”

RUCK: And then what happened? You wised up.

BRODERICK: Well, you gradually get used to somebody’s tricks, and it becomes less interesting.

RUCK: Before it got stale. When I write my memoir, that’ll be the title: “Before It Got Stale.”

BRODERICK: But we have to be careful, because we make these jokes on video and then they get typed and it looks like you’re not kidding. I thought you were really, really special from the first read-through of that show. And if I had any influence on Ferris Bueller, it was only because I thought you were so good and so right for the part. I just thought you were a very special actor, and I still do.

RUCK: Thank you. I appreciate it. So you’ve got a play, a movie, and a television series, all happening at the same time, right?

BRODERICK: Well, it sounds like that, but the TV thing that’s coming out in August, I shot a while ago. But everything seems to be suddenly happening at the same time. I did Only Murders in the Building recently, so I haven’t done much professionally since the summer, truthfully.

RUCK: But then you’re getting back on stage.

BRODERICK: I’m about to, yeah. I’ve got a bunch of stuff coming up, so I guess I’m not retired. I thought I was retired, but I’m not.

RUCK: Do you want to retire?

BRODERICK: No. I might say that once in a while, or even feel it, but I really like working. I still absolutely love it. Don’t you?

RUCK: Yeah. Absolutely. I like to be on a film set. I go to visit my wife on her sets and everybody’s nice to me, but I feel out of place. It’s like I’m not supposed to be here, but if I’m a part of the puzzle, I think it’s thrilling, and I like the doing of it. I don’t like to watch myself. Do you?

BRODERICK: No. I don’t like that. I think it hurts people’s feelings when they say, “Did you watch? We just sent you the episode. You’re incredible. Watch it.” I say, “Oh, I didn’t watch it.” It can hurt a director’s feelings, but I think it’s vanity. I don’t really care for seeing what I actually look like.

RUCK: I was horrified the first time I saw myself in a movie. They were shooting over my shoulder and I was like, “Holy shit, this is what I look like from behind?”

BRODERICK: Now, in all serious. I have some questions. You say that about watching yourself, but at the Succession premiere you were sitting there in the audience.

RUCK: Yeah. With this show, just because this show is so good and all the other actors are so wonderful, I do watch this show.

BRODERICK: Yeah. It’s so good.

RUCK: It’s wonderful, and the writing inspired everybody, the score by Nick Britell, the production design, everything is beautiful and also strangely repellent.

BRODERICK: It’s not really a happy story, but my god, it’s good. The cast is so strong and the writing for them. Like, I don’t know if it’s the chicken or the egg. I could assume it’s both.

RUCK: I think it’s both. Early on, the writers picked up on Nick Braun’s rhythms as cousin Greg and they found his speech patterns. He has a particular sort of—

BRODERICK: It’s amazing. All of you. Everybody’s their own thing, and they all have enough. It’s really quite something to watch.

RUCK: Kieran Culkin said about me, “I don’t think they knew who Connor was until you showed up, and now I think it’s just Ruck.” I’m not sure how I feel about that. I think I’m always just Alan in different clothes.

BRODERICK: I think everybody is, though. I know Kieran’s not really like that, but he is like that. Everybody, when they’re good, is showing themselves in some way. But I also wanted to tell you, when we were watching Succession, particularly your scenes, everybody’s scenes, how well they played to the audience has to have felt good to you. You got every laugh. It was all timed perfectly. And I thought, “That must be a nice feeling.” Everything you found funny about it, they understood and found funny, too. Do you know what I mean?

RUCK: I do, and I think that’s all because of the writing, Jesse Armstrong and the whole gang. His whole writer’s room is populated with award-winning playwrights and people who have created their own series. It’s just like a dream team, and I think it’s the way they write it and the way it’s edited. Mark Mylod, for instance, he’s our producing director, and he directs the lion’s share. He knows exactly what he wants to shoot and how he’s going to put it together. Matthew MacFayden said, “The writing’s so good, sometimes I feel like I just have to put on the clothes and show up on set.” I don’t think I’ve ever had an experience exactly like this. For years on end, just having something wonderful. And during the hiatus, just knowing that in six months, you’re going to go back to that amazing job.

BRODERICK: Now I’m just getting jealous. Now you’re pissing me off.

RUCK: I think you need to have your own Only Murders in the Building. Natasha Lyonne is doing that Poker Face right now. I mean, I could see you doing something like that, where you’re like Mr. Monk or Colombo. Let’s pitch it. Or we’ll do a show, you and me together, just two old fuckers, I think.

BRODERICK: Yeah. That’s a nice idea.

RUCK: Yeah. It’s a good title. And you have to write it. You wrote that thing about Richard Feynman with your mom, didn’t you? [The 1996 film Infinity]

BRODERICK: Yeah, but I didn’t really write it. She wrote it. I wrote a little. I mean, if I’m with somebody, I can help sometimes, but I’ve never been able to really sit there and write something. Like Kenny [Lonergan], Kenny sits in front of a computer or a typewriter and pulls it out of thin air. I worked with Warren Beatty and he said, “Why don’t you generate your own stuff?” I said, “I can’t. I don’t have any ideas.” And he said, “Bullshit.” So that traumatized me.

RUCK: No, wait. What did you do with Beatty?

BRODERICK: Oh. I did a movie called Rules Don’t Apply. It was about Howard Hughes.

RUCK: Oh, yes.

BRODERICK: This is the old man show that we should do, where we don’t remember our own history.

RUCK: Who are some of the other giants that you’ve worked with?

BRODERICK: I’ve worked with a lot of giants. The first movie I did had Jason Robards, Donald Sutherland. Marsha Mason, Dody Goodman [Max Dugan Returns].

RUCK: You just jumped in the middle of the lake and started swimming. You were born to do it, no doubt.

BRODERICK: It’s so great to work with people who you’ve admired since you were a kid. I’m sure you’ve done a lot of that, too.

RUCK: I got to work with Tommy Lee Jones about a year ago. He was a lot of fun. Jamie Foxx called him an “Old Lion,” and I think that’s a pretty good description of him. He’s really a sweetheart.

BRODERICK: I read that you preferred to watch this show every week like the fans do, instead of watching screeners in advance. Why is that?

RUCK: Part of it is the security protocols are so dense to actually get to the screener, you have to have two devices, and you have to download something onto one, and then they have to check your identity on the other.

BRODERICK: Oh. Jesus Christ.

RUCK: I’m lazy and it’s a pain in the ass, so I don’t do it.

BRODERICK: That’s a great answer. It seems like just yesterday we were on Broadway together in Biloxi Blues. And we both did The Producers. Do you have a desire to work on the stage again?

RUCK: I would do a play in New York with you, but the eight-show-a-week thing, I don’t know how you do it. Nathan Lane is remarkable to me because he’s my age and he just loves the stage more than anything. The last time I did a play was 17 years ago, when I met my wife. And the play was not entirely successful, but I did meet Mireille [Enos], and other people in the play were very good. They wanted me to look younger so they dyed my hair, but I looked like I had shoe polish on my hair.

BRODERICK: I remember that. We ran into each other in the street.

RUCK: Yeah, you were working across the street doing The Odd Couple.

BRODERICK: Yeah. When a play isn’t going great and you have to keep doing it eight times, that is a bit of a grind. But if it’s going well, you have your day free, and then you’ve pleased everybody at night. It’s a pretty nice life, I think.

RUCK: I would love to be in a funny play with you. Are you in rehearsals for Love Letters? That’s the play you’re going to do.

BRODERICK: Yeah, but Love Letters, you just sit at a table and read. I did it 30 years ago or something like that with Helen Hunt.

RUCK: Oh, of course. I just saw her the other day.

BRODERICK: Oh, you did?

RUCK: Yeah.

BRODERICK: How was she doing?

RUCK: She’s fine.

BRODERICK: Did she mention me?

RUCK: Actually, she did.

BRODERICK: Oh, good. You just recently shot The Burial with Jamie Foxx, right? What can you tell me about that?

RUCK: It’s interesting. It’s based on a true story. There’s this guy in Biloxi, Mississippi, of all places.

BRODERICK: Wow.

RUCK: How about that? He owned funeral parlors. He had a half a dozen funeral parlors, and he was like, a war hero and a good guy, and everybody loved him. He ran into trouble. Because I never knew about it, but burial insurance, that’s a thing that you can buy, so you pay every month and then when you die, everything is taken care of. But since it’s basically banking, you have to keep $1 million cash available. And he dipped into that money, and he was being hounded by regulators and everything.

BRODERICK: Wow. I have another question for you. When people recognize you now, is it for Succession? They don’t say, “Is this your day off?” I assume.

RUCK: Sometimes they want me to talk like Mr. Peterson. They want me to do the phone call. But people do clock me on the street for Succession.

BRODERICK: And what do they say?

RUCK: They just say they love the show. “Are you going to be president?”

BRODERICK: And what do you say? “I can’t tell you.”

RUCK: Yeah. I say, “HBO has assassins everywhere, and they’ll never find my body, so I can’t tell you anything.”

BRODERICK: And when you do this show in New York, where do you live? Do you have a place here?

RUCK: No, I don’t have a place of my own, but I stay at this hotel called The Wythe in Williamsburg. I started staying there because the production company had a deal with them, so we got a bit better rates on the room, and I wound up really liking that neighborhood.

BRODERICK: Yeah, great neighborhood.

RUCK: There’s little restaurants, bars that you can walk to if you want to meet somebody after work. But I can’t ask you any of that, because then people will know where you live.

BRODERICK: Oh, they know where I live.

RUCK: How long have you been in this place?

BRODERICK: Only about two years or less. We moved a couple of blocks. But it’s bigger, so everybody has their own room now. We have teenagers now, so they didn’t really want to share their room. But on the other hand, it was kind of nice to hear their little screaming, fighting voices in the evening.

RUCK: And what is James studying over there at the university?

BRODERICK: He majors in Classics. I’m not even sure I understand what that is, but he takes Latin. He has a philosophy class, a poetry class. I guess English is what he likes, and music. He has a composition class. He’s the smart Matthew. Actually, you know what? I’m sick of putting myself down. I’m just smart in a different way.

RUCK: Well, all my kids are smarter than me.

BRODERICK: They’re supposed to be, right?

RUCK: I hope so, because I’ve been fooling people for years.

BRODERICK: Let’s see if there’s anything interesting for me to ask you.

INTERVIEW: Alan, who would Matthew play on Succession?

RUCK: Oh, that’s good. Well, they love politics, Jesse and the gang, so it’d have to be something where you could be a campaign manager, a fixer guy who’s sweeping up everybody’s shit, trying to keep things together and with limited success.

BRODERICK: I love it. I’ll do it. You came up with that so fast.

RUCK: That would be good for you, someone who has to take care of idiots.

BRODERICK: That’s a nice idea. And I guess he would be super handsome, right?

RUCK: He’d be very good-looking with an enormous penis. I mean, a penis so big that he could be like a bumper jack. You could hoist a Buick with it. That should be in the character description.

BRODERICK: Yeah. This sounds really good.

RUCK: We’d say that you’re like, 52.

BRODERICK: Wow. There’s no way I can turn this down at this point. I’m in. Are you going to miss Connor Roy?

BRODERICK: By the time the show ends in eight weeks or whatever, I think we will have mined every little nugget that we could have out of this particular story. I’ll miss the people, terribly, and not just the actors, but the directors. I’ll miss the beautiful writing. Everybody was just a pleasure to work with, and everybody had that quality of “Yes, and,” so anybody would be given their particular task and they would say, “Yes, I can do that, and what if I do this and add this extra little…” and it was always inspired. Everybody, props, wardrobe, everybody. I saw cameramen do it 100 times. It’s like, “Can you give me a shot of Sarah on this?” “Yes, and then after that, I move over here, then I can get all this.” Everybody was just dialed in, so I’ll miss that, but hopefully that exists in other places.

BRODERICK: I wouldn’t be surprised, and don’t you think there might be sort of spinoff stories from this?

RUCK: I really think the only one that could really work would be Tom and Greg, Matthew MacFadyen and Nick Braun, because they call themselves the “disgusting brothers.”

BRODERICK: That’s a good show.

RUCK: It would be a different show. But yeah, I’ll miss it.

BRODERICK: I bet you will.

RUCK: But also, I think, in a way, I’m relieved, just because it’s a sad place to go. I mean, they’re a miserable group of people who will never be happy.

BRODERICK: Yeah, I know what you mean. And it’s nice to go out when you’re still at the very top of your game, I suppose.

RUCK: What about you? Was there a thing you did that, when it was over, you had a little period of grief?

BRODERICK: I think when I was starting out a little bit, when I did Brighton Beach Memoirs.

RUCK: Oh, yeah.

BRODERICK: It was my first lead, and it was a big success, and I left a little early. I actually left before my contract was done because I got a movie and I was like, “Well, fuck that, I’m going to do this movie.” That’s when Gene [Saks, director of the play] said, “If you don’t stay one year, you don’t really own the plot.” But I said, “No, I’ve got to go.” And I was pretty sure of that decision, but when I was on the plane leaving and I had seen the other actor in my outfit, I might have even seen a little of the show with him, I was like, “Wow, I don’t know if I was right to leave.” It was an intellectual decision, but I remember actually crying a bit, because I was 20 years old.

RUCK: You were 20?

BRODERICK: Yeah. It had been a very dramatic year and there was something about that part being gone and somebody else being in my little outfit, I did feel a pain come on.

RUCK: What did you leave to do?

BRODERICK: It was Ladyhawke, actually, which was very exciting. I was going to Rome and all that.

RUCK: I remember you told me a story about your dad that I always loved, that your dad was ill. He may have been in the hospital, but you got to go in and tell him that you got two things booked at the same time, a play and a movie, and he was so happy and proud of you.

BRODERICK: Yeah, that’s right. I got Brighton Beach, and then Max Dugan Returns. I’d never done a movie. On that day, they cast me in both of them and I was stunned. But then I called my dad. He was still home, but he was very ill and scratchy-voiced. He had cancer in his throat. I told him and he was so genuinely happy and excited by it. That was the first time I thought, “Oh, this is pretty good.” You know what I mean? I remember the generosity of his reaction, which I guess is what parents do, but he was an actor, and there was no ounce of competitiveness. He was just absolutely, purely delighted for me. For some reason, I hadn’t really expected to hear that in his voice, and it was a big moment.

RUCK: Yeah. You have that for the rest of your life.

BRODERICK: Yeah, yeah. Well, that’s not really about you, but there we are.

RUCK: No, it’s about us.

BRODERICK: It should be about you.

RUCK: Well, it’s not over.

BRODERICK: The race between us has only just begun. Don’t be a stranger, Alan.

RUCK: I love you, pal. Bye-bye.

BRODERICK: Love you too.