BACKSTAGE

Inside the New and Ambitious Revival of Oscar Hammerstein’s Show Boat

Oscar Hammerstein II and Jerome Kern’s Show Boat made its Broadway debut in 1927, making it one of the earliest American musicals still performed today. It introduced standards like “Ol’ Man River” and “Can’t Help Lovin’ Dat Man,” and its depiction of Black life in America has generated debate for almost a century. Now, Show Boat is receiving its first New York production since it entered the public domain.

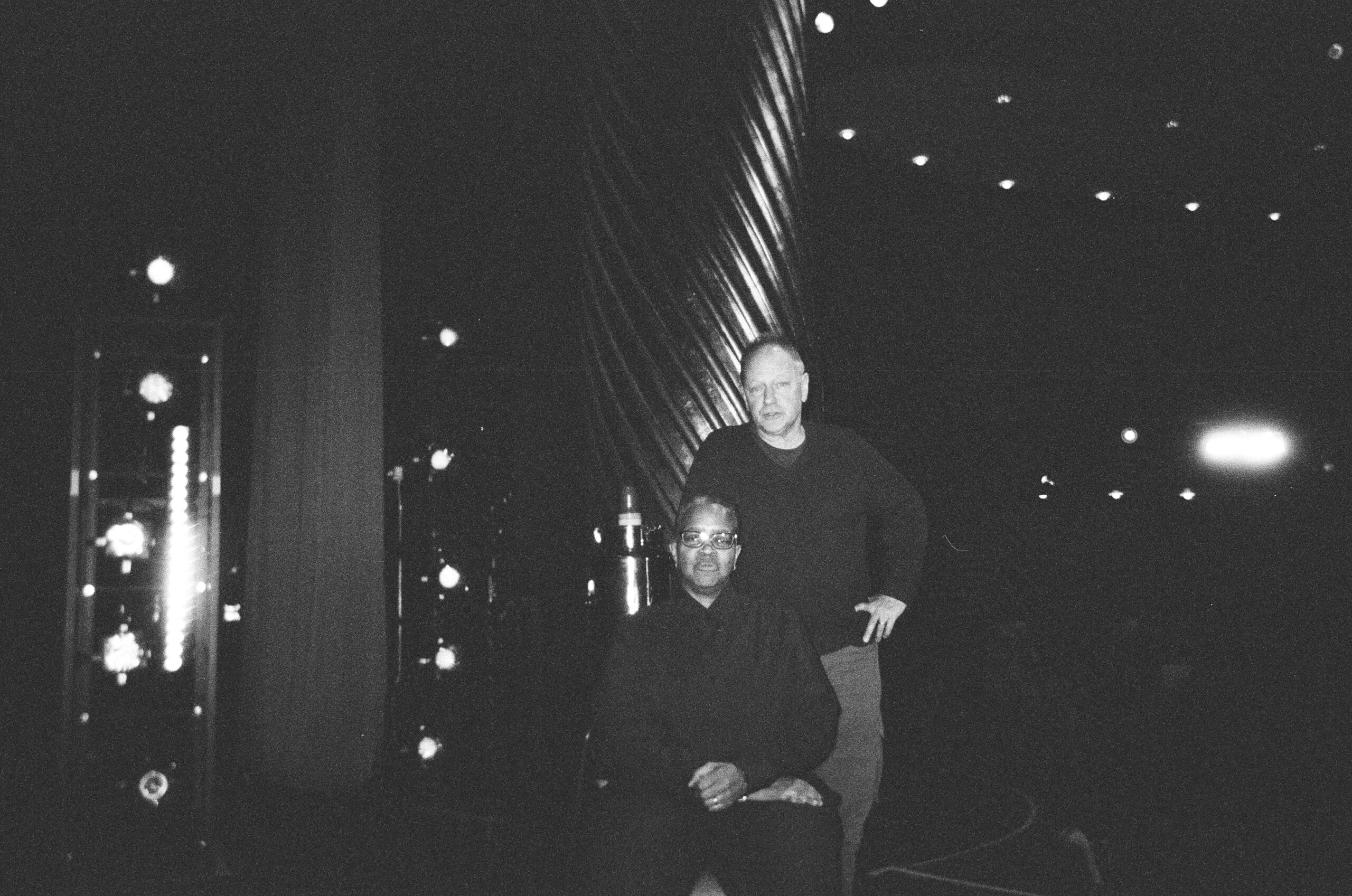

Target Margin Theater’s Show/Boat: A River opens at NYU Skirball on January 15. During a dinner break in rehearsal, director David Herskovits and co-music director Dionne McClain-Freeney told me their production is more than just a revival—it’s a chance to reckon with the show’s history and inject new urgency into a musical that’s always had something important to say. We sat down to discuss copyright law, the show’s history of blackface, the controversial number “In Dahomey,” and how they kept the show’s identity while adding new music.

———

DOUGLAS CORZINE: First of all, it’s great to be here during rehearsal.

DAVID HERSKOVITS: Thanks for visiting. I’m glad.

CORZINE: Absolutely. I’d love to just ask to start how you both first encountered Show Boat, if you remember.

DIONNE MCCLAIN-FREENEY: Gosh. I think my first encounter with Show Boat was probably more with the music than it was with the actual piece, probably because the songs are part of the great American songbook, so of course “Can’t Help Lovin’ Dat Man of Mine” or “Ol’ Man River.” And then over the summer, David and I started talking and it encouraged me to take a deeper dive. I think I’ve watched two or three different versions of Show Boat and had a partial read of the Edna Ferber novel for a little background, and I went from there.

CORZINE: What about you, David?

HERSKOVITS: Well, most people I encounter know Show Boat the way I first knew Show Boat, which is that I didn’t know Show Boat at all. I just knew a couple of songs from it for the reason Dionne was saying, because they’re in the culture in a different way from the show itself. At Target Margin Theater, we read and think about and talk about source material all the time. We actually read the original book and lyrics for this material about 12 or 14 years ago around the table in the office. We read it because it connects to a number of different interests that we have been pursuing for a long time in different ways. Some of them are just the musical content, but also the content of the show as an American document and as a cultural document that contains all of the obvious problematic material in the show. So we looked at it for that reason and immediately felt like, “Oh, this is something we could work on.” But then, you know how it is, you’ve got a whole bunch of different stuff bubbling around in your head at different times. So it just stayed there, but then we read it again over the pandemic and did a little more research, and by then, we were really saying, “Okay, let’s do a musical.” Then Jay Wegman, who runs the Skirball Center and has been a supporter of my work for a long time, was excited about doing a musical with us. So that really pushed the conversation forward over the last couple of years.

CORZINE: Where did Show Boat entering public domain intersect with your journey there?

HERSKOVITS: Exactly at that point. I was talking to Jay about different materials. He had different ideas about musicals that might be interesting, but then two summers ago it entered the public domain and then it was like, “Well, now we can really do whatever we want with this.” Because it’s not easy to get the rights to work on this material. The people who control it are very protective of it for various reasons and I think artistically, that’s a shame because the works can stand up to all kinds of treatment. But the way the theater business works, it’s a property that you have to protect, and the value of the property comes from preserving it. My own personal view is the opposite, which is that productions may succeed or fail, approaches may succeed or fail, but the work is strengthened by that.

MCCLAIN-FREENEY: I think works in the public domain really are like colors on a palette, where now you have a chance to paint the kind of painting that you see, which encourages artists to keep making art because then they’re not constrained by what a thing is and only being able to do that. I think it creates a sense of adventurousness, and I think the best art comes out of being adventurous. If we operate out of excessive caution, then everything looks the same. We wind up with beige. Beige everything.

HERSKOVITS: I second that so strongly.

CORZINE: What does that do for you, Dionne, as music directors on this as a project? Today I saw the “In Dahomey” number, which is not always included in modern productions of Show Boat.

MCCLAIN-FREENEY: The way that we arrived at “In Dahomey” was that it was one of the pieces that had been cut, but we included it and it sits in a larger context. It comes at the end of a visit to the World’s Fair, and while the framing of that is lovely and quite palatable, the idea that onlookers come to watch people on display is a human zoo. If you can imagine, for example, Saartje Baartman, a South African woman whose dignity was totally stripped from her because she had a large backside that was seen as an oddity, which oddly enough inspired the bustle as a fashion piece. But this poor woman was often either scantily clad or completely naked and put on display, and she was poked and prodded and pawed and all the kinds of things that you can imagine would’ve happened. We’ve seen human zoos in parts of Europe that had colonized parts of Africa and then chose to put people on display for white onlookers. And for me, this moment was no different. So I was familiar with a Zulu folk song called “Dumisa” and I thought this would be the right pairing with “Dahomey.” The way that the songs are tied together is, you have this group of Black people who are singing “What is a Song of Praise,” which is a joyful moment for these Black folks who have just labored and labored and labored, and then “Dahomey” continues with this nonsense language that the white onlookers sing. And for them, it’s gibberish. But then the song concludes with, “Where is home?” Because ultimately, how you are with your people, your family, your community, your friends—one of the hallmarks of home is how you communicate with each other.

HERSKOVITS: To me, it was a question of, “Well, we don’t have to do Dahomey Village. The only reason to do it is if we can use it in ways that are going to be meaningful to us now and add something.” And what I love about the way the Dahomey Village thing ends is that the white people go away. They’re afraid. They see the Black singers and they say, “That’s scary. Let’s get away from these people.” And then the Black people say, “Well, thank god they’re gone. We’re glad to see them go.” That’s all original in the text, so in a certain way, even though what we’re doing is reinventing it quite radically, it’s also an account of the original material.

CORZINE: The show as it stood originally was already full of interpolation. “Bill” is not original to this show. And I don’t know if you all are doing “After the Ball”–

HERSKOVITS: No, we’re not. Exactly. Thank you for saying that. I’ve embraced that and found the people who also feel that way. You’ve got to find the right people, because it’s a different way of writing, of composing the work.It’s like, sure, they took [“Bill”] from P.G. Wodehouse, but we don’t need to do that. I think I’m the only person in our group who knew “After the Ball,” and I’m not quite sure why I did.

CORZINE: I knew “After the Ball” because of Taylor Mac.

HERSKOVITS: Right – I knew it from some other lifetime: it’s like an old English music hall song. But why do we have to do that? The question to me in adapting it is, “What’s happening here dramatically? What’s happening in the story and what is the way to make that happen now?” And that’s exciting to me.

CORZINE: And so if “After the Ball,” to Hammerstein and Kern, was this famous song that the audience would immediately respond to, what’s that answer for you musically now?

HERSKOVITS: Well, I said, “What do you think we should use here?”

MCCLAIN-FREENEY: And I said, “Well, let me think about that,” and I wound up writing a song.

HERSKOVITS: So it’s really new.

MCCLAIN-FREENEY: It is extremely new and written for this production, keeping in mind who is singing it and what story would they tell.

HERSKOVITS: That’s what we worked on. In a certain way, we didn’t pick a song that anbody would know. But we can turn it into a sing-along on stage and use it in a dramaturgical way, in a narrative way, in a characterological way, the way that music can function so beautifully.

CORZINE: Yeah.

MCCLAIN-FREENEY: I’m going to be the bugaboo here about the definition of a play with music versus a musical. From what I understand about a musical is that the songs all have functions. They are character songs, they move a plot forward, they’re functional, where not a lot of the music in Show Boat does that. There’s no quest song in that musical theater way. So every now and then, I would put in some things that would veer closer to that definition of musical theater. I think I did that in our “New Year’s Eve” song.

CORZINE: Yeah, absolutely. You were talking earlier about people who are presented as Black characters in a certain moment, and how Show Boat has a complicated history with that. In the original production, Queenie was played by Tess Gardella in blackface. How are you all engaging that legacy or responding to it?

HERSKOVITS: Well, let’s face it, for many, or maybe most people, Show Boat is radioactive. It’s amazing material, it’s wonderful. The songs are beautiful but you wouldn’t want to do it. I’m doing Show/Boat: A River not to try to solve those problems, or to try and flatten them out or cover them over, but to try to reframe them in a way that is meaningful to us today. Because I believe, as an account of American history, this document is meaningful to us, and it’s relevant today. But the basic theatrical commitment that I make here is that I’m going to assemble a group of people who are diverse in every way. Diverse, diversely talented, they bring different strengths, they bring different identities, they bring different physical presences. I’m talking about the cast, but I’m also talking about the people developing the music, the people who have worked on the movement with me, the designers. And let me be clear—that’s not some piety. That’s because I think the work is better for that. Stephanie [Weeks], who was there at the very first reading that we did years ago of this material,is an artist I’ve worked with many times over the years and I admire a lot. I made a determination that Stephanie was going to play the role of Julie. Now Stephanie, as you have observed, is a dark-skinned Black woman. So If you picture somebody who’s passing in the early 20th century in the United States, it doesn’t look like Stephanie. So I’m now creating a challenge for myself, but also I believe in opportunity for the work and for the audience, which is to say, “Right. I need to make it clear to the audience who’s white. who’s decided to be white, who gets called white,” and we’re going to make that super clear, which is pretty easily done with markers as long as they’re very clear and consistent. And the challenge for the audience is to say, “Okay, the person on stage is not going to disappear.” But I don’t think the person on stage ever disappears. And you know what the best example of this is? Movie stars. “I want to go see that movie because so-and-so’s in it.” Every second, it’s the thrill of like, “Oh, look at what Willem Dafoe’s doing now,” or whoever the person is. Right?

MCCLAIN-FREENEY: Like Denzel Washington playing a bad guy in Training Day.

HERSKOVITS: Yeah. It’s like, “Whoa, Denzel Washington. I love that.” But I’m still with the story and if the movie’s good, I’m really with the story. People in the theater sometimes have a harder time with that, but I think we easily are capable of that.

MCCLAIN-FREENEY: Well, it’s interesting that you say that with how much pushback on social media there was with the casting of Cynthia Erivo as a Black Elphaba in Wicked. And the idea that you can only have this person or that person play a particular role. The story is the story and, just as you said, I think it’s hard for people to turn off who is the person that I see versus who is the character that I see. But I think it speaks to the question that we’re really as a society having a terrible time trying to answer which is, “Who is white? And who gets to be white?”

HERSKOVITS: And this allows me to put that question right in front of you like, “Wait, I understand if you’re wearing that thing over your shoulder that’s white, then you’re the white person.” But why is that person white now and then they’re not white. Isn’t that the point of a miscegenation story? What the hell are we talking about actually? That’s the level of reflection that I hope for. I don’t want to make it sound like that’s the only thing, but that is front and center and it’s certainly what people are going to respond to.

CORZINE: I want to tie together two things that you both said. Laurie Winer wrote a biography of Oscar Hammerstein that came out a year ago and something she says that I think is really relevant was that Hammerstein was concerned with who we are and with community, and that musical theater has become much more concerned with who I am and individual identity. I wonder what you think about this show and where it’s placed on that spectrum.

MCCLAIN-FREENEY: I definitely have thoughts about that. I come from a choral background. I’m a Black church girl. I grew up singing in choirs. I was a choir director for many years. I still approach much of what I do as an arranger and a music director from a choral perspective because choral singing is community singing. And there’s so many beautiful choral moments in Show Boat. And I always come back to the American story. Once upon a time, Americans were community-oriented—your town, your city, how you were with the people in your neighborhood. There are just so many parallels with how America has moved from a communal or a community-minded society to one that is hugely individualistic. I think musically that has happened also, but we’re going to try to bring some of that back in Show/Boat: A River.

CORZINE: Last thing before I turn off the tape, what have you had the most fun doing in the process of this show?

MCCLAIN-FREENEY: Wow.

HERSKOVITS: It’s hard to choose.

MCCLAIN-FREENEY: It really is.

HERSKOVITS: One thing I’ll say is the conversation. I always knew if we’re going to do this, we’ve got to talk about it. Part of the work that we’re doing is to make the show and change the culture and the world that we live in, and that starts the day we gather. That has really been a joy and an excitement.

MCCLAIN-FREENEY: Some of my favorite moments are when the whole company is singing, when you hear the chord and there’s that moment where you look into the faces of the people who are singing and they also have that moment of pleasure.