BLACK BOX

How Max Pitegoff and Calla Henkel Brought DIY Theater Back to Hollywood

———

GRACIE HADLAND: What is New Theater Hollywood?

MAX PITEGOFF: New Theater Hollywood is a delusion.

CALLA HENKEL: It started as a joke.

PITEGOFF: We had been living in Berlin. A couple of years ago, we started coming to L.A. And we always had this ongoing joke about New Theater Hollywood. After we’d run this space, New Theater Berlin years ago–

HENKEL: 10 years ago.

PITEGOFF: –we thought it would be funny to open it in Hollywood. It was this joke that we kept on repeating. We started talking to people about it without really thinking it would become this actual black box theater.

HENKEL: New Theater, which we ran 10 years ago in Berlin, was a theater that we opened after running a bar. It was called Times, and it was like an artists dive bar. We made this rule not to take photos in the bar, and instead we wrote down everyone who came and went. It sort of became these scripts and we had this feeling that we were running a theater. And artists were professionalizing at that moment in Berlin, so it went from a DIY-punk scene to a sort of neocon-post-internet art scene.

PITEGOFF: We were interested in bringing all of these people and their work together and having them perform in this space and having this imperfect display in a world of high gloss, post-internet imagery.

HENKEL: At Times Bar, we would show one piece of work above the bar at a time, and it always got damaged because we would have it installed where the bar was open. And so at New Theater, we had this idea that we would ask all the artists that we were working with to give us work that would function as props or as background or set. And then the scripts we wrote became these texts that bound all the work together. So it started as this idea to bring really disparate types of work together in a way that’s live and fast and not completely rationalized.

PITEGOFF: Yeah, theater is this very easy–well, I shouldn’t say easy. Theater is a really hard but structured form of collaboration, and that’s kind of what we became interested in.

HENKEL: The hierarchy is really clear, which is so relieving. And we became obsessed with German theater and the Volksbühne and this tradition of extremely political theater that came out of that town.

PITEGOFF: We came at it from such a punk perspective in the beginning, and then after three years we ended up in the Volksbühne, actually working in theater.

HENKEL: Turns out we were theater kids.

HADLAND: It’s funny thinking about theater in L.A., where it’s the lesser performing art to film and television and acting, but it does have a history here.

PITEGOFF: Yes. Underground theater in L.A. has such an incredible history that’s also not very visible.

HENKEL: No, because theater is for losers. It’s what you do when you’re not doing what you want to do. It’s on your way to doing something else, a TV show or a film. It’s very bottom of the barrel, which is fabulous for us coming from Berlin where it is an extremely high art, and being like, “How do we bring in really good art, but allow it to exist in a kind of not fully formed state?”

PITEGOFF: In L.A. there are so many poetry readings, so much stand-up, these things that revolve around an idea of theater.

HADLAND: But by having this space you’re bringing in people from a lot of different

backgrounds: artists, writers, comedians, fashion people. It’s not like you’re starting a gallery, where so many already exist.

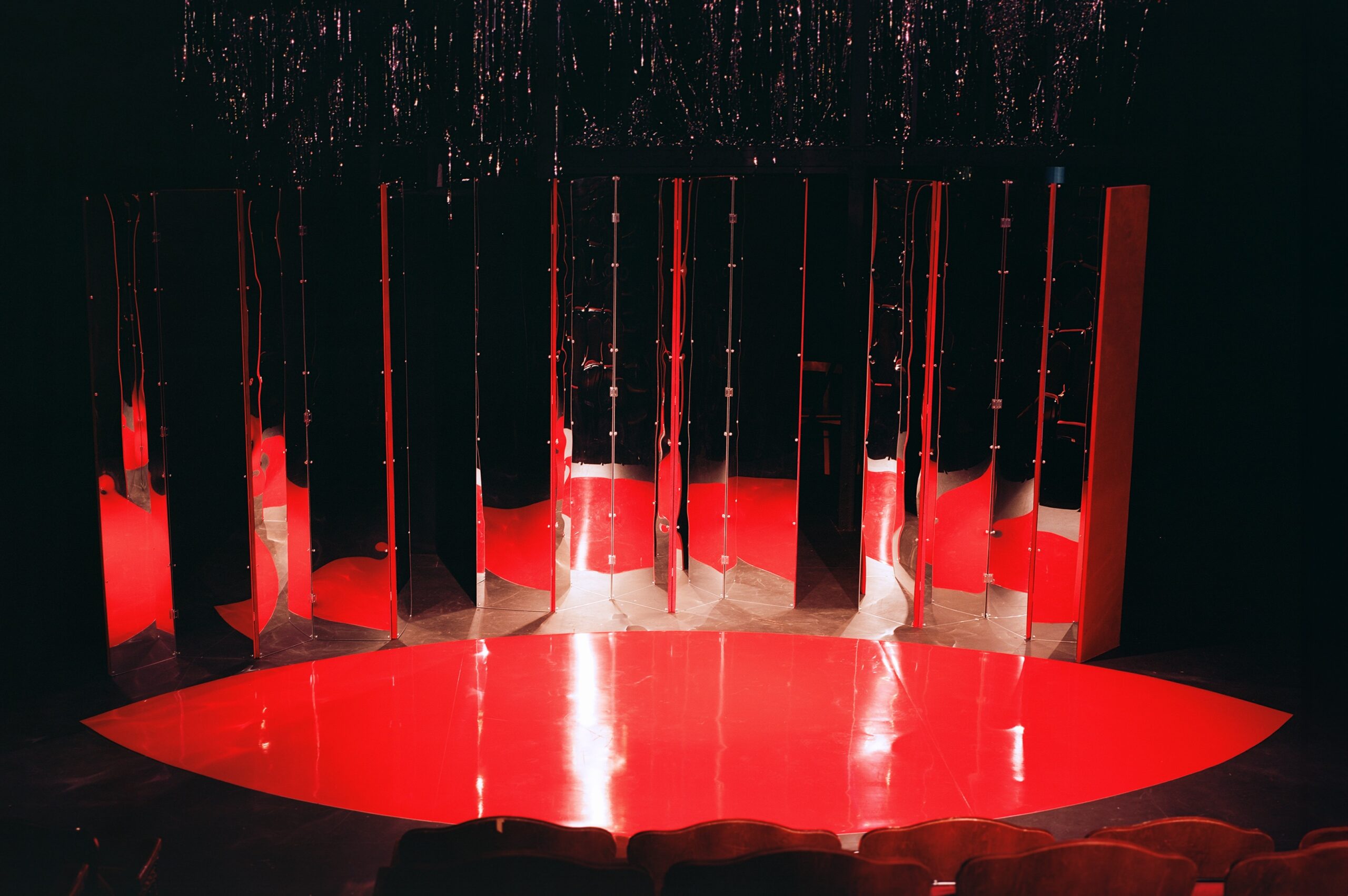

HENKEL: Part of the reason we also wanted to open a theater in Berlin was because when you perform in a gallery, it feels terrible. No one knows how to behave. Theater has this hierarchy where you walk in and sit down in a red seat and you know exactly what that transaction is. There’s something really relieving about that. In a lot of ways, New Theater Hollywood functions as a magnet because all of this work exists, but doesn’t have a place. And also, galleries have to sell work. That’s exhausting, so they make really weird, boring decisions. We don’t have to do that.

PITEGOFF: We deal with the democracy of ticket sales.

HENKEL: Yeah. It’s this completely other economy. And there’s so many people who feel like they need a place like this. So many people are already working in performance in these different, very siloed fields, whether it be TV or acting or this sort of performative poetry world, and all these things never touch each other. But in theater, they can.

HADLAND: It seems like a lot of your projects start with this big idea or fantasy, but then it becomes really logistics-based. You’re like turning lights on, hiring an electrician, cleaning up the bar.

PITEGOFF: Yeah. We have to learn so much every time we do this. When we ran TV Bar in Berlin a few years ago, I became a complete German business tax freak.

HENKEL: Max knows everything about German business tax.

PITEGOFF: I’m really happy to be in L.A. and have the sun bleach that out of my brain.

HENKEL: But we love a commitment to form. The bar was a form, and we committed to it to such an extreme degree that we had 14 employees and these intense schedules. I don’t mean to belittle it in any way, but I think the humor allows us to go as far as we can. It’s like we’re not running an institution. In a certain way, it’s like we’re performing an institution. That’s also why we can’t run these spaces forever, because they take all of our energy and our presence. And we want to give all of what we have to the people that we work with.

PITEGOFF: I also think it’s time for theater again.

HENKEL: Plus, media is really boring right now. I feel like everyone in Hollywood, post-strike, is so aware of how bad everything is that’s getting made. So it does really feel like it’s a moment for theater and recalibration and being like, “How do we get back to the part that is meaningful?”

HADLAND: Also, you were talking about these plays coming out of the bar. There always seems to be other material or projects that come from running the space.

PITEGOFF: In some ways, each space holds a narrative. It really came forward when we were running TV Bar and made this film, Paradise, over the three years of running that space. We had this kind of parallel fiction that was unfolding as the bar was running.

HENKEL: Paradise was a film that we shot on 16-millimeter when the bar was closed, so it became a sort of TV studio and a set that we used. And similarly with New Theater Hollywood, we’re working on a film that links together all of the plays loosely. As artists running these spaces, the question of documentation becomes a huge one. Our filmmaking practice is now about building in documentation and calling a false narrative into the space itself, so the space kind of functions in two ways. One is as a set and one is as this very public space, and you don’t need to know about the other to buy a ticket and come. But also we keep the processes separate.

PITEGOFF: Yeah. It’s also important to us that people who visit these spaces aren’t overly confronted with our work.

HENKEL: With TV Bar, we never showed the full film we made until the bar was closed, but now, that’s the only thing that’s left over.

PITEGOFF: And in this case, we started by making a film about someone opening a theater in LA, which we were planning before we even saw this space or realized that we wanted to open so soon.

HENKEL: Maybe when we say it starts as a joke, it’s more like it starts as fiction. It starts as a story that we’re telling each other. And it really started as this story that we had made about this character who got hit by a bus and got a bunch of money and decided to open a theater in Hollywood. We were out filming that and then we saw a sign that was like, “Theater for rent.” We decided to call, and then we saw it, and were like, “Oh, so we actually have to do this.” So there really is this thing about it starting in fiction.

PITEGOFF: And ending in fiction.

HENKEL: Yeah. And then in the middle, you and I have to learn 1,000 jobs.

HADLAND: It’s amazing. Can you talk about your funding models a little bit?

HENKEL: It was interesting. In Germany, theater is really serious.

HADLAND: It’s state-funded.

HENKEL: I call it a state-funded disco, because it was absurd how much tax money went into it.

PITEGOFF: With New Theater in Berlin, we didn’t get any of that – we were fully self-funded.

HENKEL: Every time we sold a work or had an exhibition fee, it went straight into the theater. The space came with a separate storage facility, but it had a bathroom and a kitchen in it, so we renovated it and turned it into an Airbnb. But then I had a huge mental breakdown because I was running that side of it more. I had to be like, “Hi, yeah, the neighborhood has really cute cafes….lots of bars…” And I was like, “All this language is fake. This is another script I have to write.” The funding is never sane. .

PITEGOFF: TV Bar was sustainable because it was actually a functional business, whereas theater is a hole for money. –

HENKEL: We sold a few pieces of work and put our own money into opening it, and now we’re getting by on selling tickets and t-shirts, and donations. We are applying to be a non-profit right now.

HADLAND: Oh, really?

HENKEL: And friends have donated work, which is one major way we have been able to stay open. It’s really beautiful in this way that collective projects get to stay collective.

PITEGOFF: I also think gala culture is really interesting in America.

HENKEL: Oh, yeah. We have not cracked that yet.

PITEGOFF: But our first event was The Night of Speeches, and we wanted it to have this feeling of a deconstructed, fucked-up gala.

HENKEL: Where no money got made. So yeah, fundraising in America is a new beast for us.

PITEGOFF: We’re also in this part of Santa Monica Boulevard called Theater Row.

HENKEL: Historic Theater Row.

PITEGOFF: Which is a ghost town for theaters. There are only two other functioning theaters. There used to be 20. A lot of people who come in here are like, “Oh, I performed in this theater,” or the one across the street, or whatever. But it’s always this haunted memory of what used to be here.

HENKEL: It’s haunted, but in a really positive way.

HADLAND: Could you talk about the move from Berlin to L.A.? It seems like a lot of your work relies on investigating the culture of a city. Why L.A., and what was it like to leave Berlin?

HENKEL: I think no one does storytelling like America or like Hollywood. And there’s something in my mind about making theater here that’s so perverted and exciting that I couldn’t imagine opening a theater anywhere else in the world. So for me, that’s why L.A. But we grew up in Berlin. I got there when I was 19. It’s strange to be back.

PITEGOFF: I used to love the gray winters and dark bars.

HENKEL: I love the seriousness of German culture in a way where all you wanted to do was destroy it. Because German culture shouldn’t exist for so many reasons, but it’s so well-funded. It was such a fun place to try and rebel against. And then the idea of coming here and trying to earnestly build culture is such a good whiplash in a way.

PITEGOFF: It’s such an inverse.