MUSE

Molly Ringwald and Gus Van Sant Are Still Searching for the Real Capote

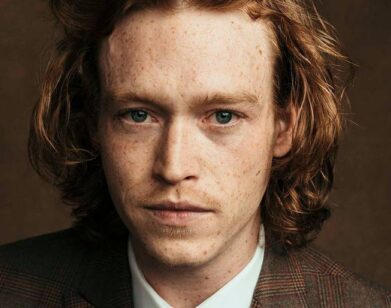

Molly Ringwald, photographed by Shervin Lainez.

Feud: Capote vs. The Swans, the new FX series produced by Ryan Murphy and directed by the esteemed Gus Van Sant, looks back at Truman Capote’s infamous and dramatic fall from grace. The writer once sat at the center of New York City’s elite, surrounding himself with a group of wealthy and powerful women who he dubbed his “Swans.” But when Capote aired their dirty laundry in a gossipy Esquire profile, he betrayed his inner circle and fell into chaotic downward spiral. Molly Ringwald, who plays Joanne Carson, the ex-wife of The Tonight Show host Johnny Carson, is still trying to figure out why he did it. “There’s a part of me that thinks that there was some anger there,” she told Van Sant on a Zoom call last week as the actor (and 1983 Interview cover girl) and director wondered about Capote’s complicated psychology. In conversation, they talked about working with Tom Hollander, Marlon Brando’s distaste for Capote, and their memories of River Phoenix.

———

MOLLY RINGWALD: It seems like everyone’s really loving it [Feud: Capote vs. The Swans]. Did you know that people were going to respond to it the way that they have?

GUS VAN SANT: No. Whenever I do something, I think it’s going to be the best thing ever. That’s what I’m aiming for. I also know that after it’s done, it’s got its own life.

RINGWALD: I’m really happy to be able to talk to you because I feel like we didn’t get to talk that much when I was working with you. And I’ve been reading this book [Gus Van Sant: The Art of Making Movies].

VAN SANT: Oh, wow.

RINGWALD: I got this before I knew we were going to do this, and I’ve been carrying it with me everywhere. I’m halfway through and I’m really loving it.

VAN SANT: I’ve read parts of it, but I was unable to read because it was about me.

RINGWALD: I find with picture books very often, the text is not that great, but this is really well-written, and I find it really inspiring to read about your creative journey and how hard it was. Then also, how you get to a certain point and think, “Now I’ve arrived,” and then you still have to fight.

VAN SANT: Is that in there? Did I say something?

RINGWALD: Yeah.

VAN SANT: Oh, okay. Yes, you still wake up to strive now, today.

RINGWALD: Do you find that it keeps you creatively seeking?

VAN SANT: Yes, because no matter what you’re making, the next thing isn’t necessarily all set. You have to make decisions on what you’re doing, who you are, where you are. It’s always about discovering something new. That’s the way I kept going. The process of learning it becomes the project.

RINGWALD: I find that really courageous. A lot of people would just say, “Okay, this is successful. People like when I do this, so I’m just going to keep doing that.” I like that you have done so many different things. I haven’t seen everything that you’ve done, but from what I have seen, there’s a through line, but it’s different. You’re breaking new ground.

VAN SANT: Trying to. Some filmmakers are able to have a thing that they keep working on through their career, and then sometimes it’s varied. There is a connection to all of them, I guess, where in almost every single thing, including Capote, there’s characters that are finding new families that aren’t their blood families, and it’s about the action and development and trials of that.

RINGWALD: Do you feel like Truman saw them as family?

VAN SANT: For sure. Babe [Paley] was like his sister, maybe even closer than family. Babe would talk about that. There was sort of not that much information for us that was direct from Babe, like quotes or anything like that. But Ryan and Robbie had made it into a thing where there was a family, especially between the two of them, and then the rest of the group.

RINGWALD: And so I guess that begs the question, why did he do that?

VAN SANT: Well, my family moved a lot when I was growing up, starting at six. My mother said, “Okay, we’re going to move to Chicago from Denver, Colorado.” I didn’t understand it. Moving to a different city, as a 6-year-old, was kind of unbelievable. She would say, “Open new doors, open new windows.” I was like, “Okay, open new doors and windows,” but then it was terrifying.

RINGWALD: That must’ve been stressful.

VAN SANT: Very stressful. You get to the new location, and then you form a new group of friends. A couple of years after that, we moved to the San Francisco area. And there was, again, a pattern of finding new friends. Then a year after that, we moved to Darien, Connecticut, and again, finding new friends. Some of their families moved from San Francisco to Connecticut as well, so there were some people in my class that I had in the same grade school in California.

RINGWALD: Wow.

VAN SANT: Or in the grade school in Connecticut, which is very strange.

RINGWALD: Does that mean that Capote just didn’t really know how to be a friend? It’s something that I think about a lot, and I’ve been asked why he did it.

VAN SANT: Right.

RINGWALD: There’s a part of me that thinks that there was some anger there.

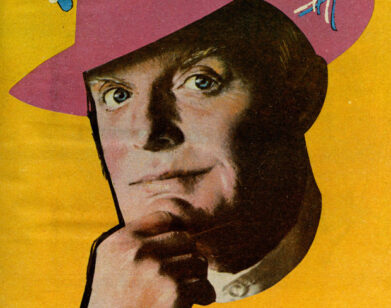

VAN SANT: There probably was. I wonder if he was conscious of it, or whether it was a below the surface anger so he did it without meaning to, but psychologically to satisfy something deep inside of himself. I bought this book, which is really cool [The Duke in His Domain]. It’s about [Marlon] Brando. He is in Kyoto, doing a movie called Sayonara. Capote was sent to Kyoto to report about Marlon acting in this big film. And it wasn’t going so well because the book that the film was based on wasn’t showing Japan in a good light, so they were turning against production and weren’t allowing them to use any of the real Kabuki actors. It worked against the film, and Brando’s complaining and giving up and saying, “I’m doing it for the money anyway.” He’s abandoning the project while he is doing it. And Capote’s there explaining that, and also really doing a character analysis of Brando, making him look really odd. Capote had kind of assassinated his character in a way. To me, it reads like a regular story, but you could see how, if you were Marlon, you probably would be really angry.

RINGWALD: Did Marlon ever comment on it?

VAN SANT: You can see in talk shows sometimes they would bring up. I remember seeing one of Truman and Marlon talking about each other, and they would say bad things about each other, but I don’t think they got into a feud or anything.

RINGWALD: I just translated a memoir about Maria Schneider, who had famously done Last Tango in Paris with Brando. It seemed like Brando had no problem talking about anyone. He didn’t talk to [Bernardo] Bertolucci for 15 years after they made Last Tango.

VAN SANT: Yeah. He was mad.

RINGWALD: He was mad for a different reason than Maria was. Maria was angry because of that scene that she felt like was sprung on her. There was a lot of sex and grittiness, and she knew that it was daring and audacious, but that specific scene was filmed without consent. Maria didn’t hold it against Brando at all, but she really hated Bertolucci. And Brando was angry because he felt psychologically misused.

VAN SANT: I’ve heard that. A friend of mine, Mike Pitt, did a Bertolucci movie, The Dreamers. He was trying to explain that there was this thing that Bertolucci would do, which would be showing them their inner selves. Mike was saying it was uncomfortable, and it was a famous thing that happened to Brando.

RINGWALD: How do you feel as a director about that?

VAN SANT: I’m really afraid to go to lots of places. I’m timid about going too far or being too intense. I try to let the actors lead it if it’s a hard scene.

RINGWALD: Yeah. I work well with that style. If somebody is letting me discover it, we’re discovering it together. I feel more free than if somebody is manipulating me.

VAN SANT: Right. For me, that seems to work. But then you hear about famous situations where the director needs to have the actor be in complete turmoil. They’ll turn on the actor and make them feel horrible so they can get that moment.

RINGWALD: Yeah, I don’t really like that. I’ve worked with a lot of American actors who generally do some version of the method, whether it’s Strasberg or Adler or Meisner or whatever. A lot of times, if you’re playing a character that’s as challenging as Truman, [in order] to get everything right, they would just stay in that character. It was so interesting working with Tom [Hollander]. The way he would go from being Tom to Truman was really amazing. It was like watching a magic trick.

VAN SANT: He said that he didn’t stay in character when I first talked to him, but he was so intense in character.

RINGWALD: I loved it. In a lot of ways, it made my job easier because Tom is so charming and gracious. I immediately fell in love with him, and then it was easier for me to sort of carry into Joanne [Carson]. Joanne was the only person who kind of loved him unconditionally.

VAN SANT: That’s great, the relationship you guys had.

RINGWALD: What was the experience like for you?

VAN SANT: It was really hard because I’d never worked quite that fast with an intention to have it look a certain way. So, I didn’t get a lot of sleep.

RINGWALD: Had you done television before?

VAN SANT: I’ve done a couple of first episodes for a couple of different series.

RINGWALD: Yeah, I started out with film. But I’ve been doing a TV show for the past seven years and it just ended, so I got used to working that fast. Feud seemed really not fast to me compared to other stuff. It seemed almost like I was doing a film again, which felt luxurious.

VAN SANT: That’s good. I try to make it like that when we’re shooting, as if there’s tons of time.

RINGWALD: Another thing I’ve been reading about in this book is that you say that at a certain point you realized that film couldn’t be your only artistic medium. That really spoke to me because as an actor. I realized at a certain point that I was going to go crazy if that was my only artistic medium, because you have to depend on somebody to give you a job. So I started to take writing seriously. I sing, I translate, I do all these other things. They all feed each other, and I find it a lot more emotionally satisfying. Has that been your experience?

VAN SANT: As a director, there’s so many disciplines, writing being one of them. You can write and you can be the photographer or cinematographer. You can be the set designer. That quote likely comes from when I was starting out, when I really was painting and not making films.

RINGWALD: Do you remember that we met a long time ago?

VAN SANT: For To Die For? Yes, and I took a picture. I still have it.

RINGWALD: I wanted that part so bad. I remember we talked a little bit and you asked to take my picture and I was so surprised. I’ve always wondered if it was a good picture or not.

VAN SANT: It’s a great picture.

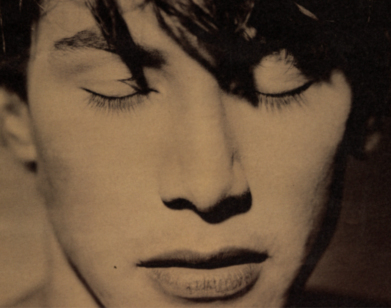

RINGWALD: And we have a couple of other things in common. One is that River [Phoenix] and I worked together.

VAN SANT: When was that?

RINGWALD: We did a TV movie called Surviving. I was 16 and he was 14, and he was so good. It was about teen suicide, and Ellen Burstyn plays his mother. It was a really good movie, but River’s performance was outstanding.

VAN SANT: He was incredible. On My Own Private Idaho, he would write all these notes in his script so that if we were shooting out of order, and his character’s walking through a doorway and you’re going to pick it up on another location or another day, he would do something when he walked through the doorway, like sneeze or walk backwards so when you picked up the other side of it, he would sneeze to make it match. I thought it was a strange detail but useful for the editors.

RINGWALD: That’s so smart. Did you ask him if he made that up or if somebody told him?

VAN SANT: He just thought it was a cool trick.

RINGWALD: Do you think that, had River lived, he would’ve ended up directing or making his own movies?

VAN SANT: Probably, because he loved the idea of writing. What he really wanted to do was play music. He was making a record and had a band.

RINGWALD: Yeah. So what are you doing now? What’s your next thing?

VAN SANT: I’m playing around with different ideas, and just taking a break from Capote.

RINGWALD: Yeah.

VAN SANT: Were there any things related to Capote that you were working on before you did the role?

RINGWALD: The first thing I ever did when I was three years old was a play based on a story of Truman Capote’s called The Grass Harp.

VAN SANT: Oh, wow.

RINGWALD: I didn’t have any lines. I play one of Baby Love’s illegitimate children. So I’ve known about Truman Capote since I was three. Then of course, in the ’70s, Truman was still alive and melting down on national television. So I can remember watching him on Johnny Carson and Dick Cavett, whatever my mom was watching. Then, as I got older, I read his stuff. In the ’80s I was approached by the Truman Capote estate to do a remake of Breakfast at Tiffany’s, because apparently Truman never felt like Audrey Hepburn was the way that he had written the character.

VAN SANT: Right.

RINGWALD: Physically she was supposed to have been more like Carol Matthau or Marilyn Monroe, more voluptuous and not so chic. I would’ve loved to have done it but I thought I would’ve been crucified, because Audrey Hepburn as Holly Golightly is more well-known than the actual novella it was based on.

VAN SANT: Was that made?

RINGWALD: Not as far as I know. I try not to have regrets, but there’s a part of me that regrets that I didn’t do it. When I’ve been reading your book, the fact that you remade Psycho frame-by-frame is so courageous. I love that you did it as an art experiment, you know?

VAN SANT: Yeah. That was a confluence of ideas that came together, partly taking something and making it in your work. Usually it’s an object. You’ll take a ready-made Marcel Duchamp bicycle wheel and you’ll make that the art, or a urinal in his case. In this case, the object was a movie.

RINGWALD: Were you surprised by the reaction or were you anticipating it?

VAN SANT: I was told by Danny Elfman, who did the score, “They’ll kill you if you remake Psycho.” I said, “I know, but will you still work on it?” He said, “Yes.” I thought to myself, the critics will kill me. And then they did. Then I realized it doesn’t really feel good.

RINGWALD: Did it bother you?

VAN SANT: It bothered me when it was happening, but I’m not sure why there was a problem, because Anthony Perkins was remaking Psycho again and again. But the idea of not changing it was somehow a challenge for the film teachers and writers of the world. They felt that was challenging the master.

RINGWALD: I feel like it’s actually respectful.

VAN SANT: Yeah. I was trying to respect the director’s work.

RINGWALD: Has anybody ever remade any of your films?

VAN SANT: Yeah. James Franco has been remaking My Own Private Idaho, re-editing it and re-shooting parts of it.

RINGWALD: Did you feel like it was interesting, or did it feel like somebody was sneaking in and taking clothes from your closet?

VAN SANT: A little bit. I was curious and a little paranoid but I thought, as a concept, it was interesting.

RINGWALD: People have asked me how I would feel if The Breakfast Club was remade, but I think John Hughes put in his contract that they can’t do it without permission from his estate. I also feel like it’s so much of a certain time that it would be weird, in a way, to remake them.

VAN SANT: That’s true.

RINGWALD: It’s been really nice talking to you. I hope that we can continue this conversation.

GUS VAN SANT: You too. We should definitely hang out.