IN CONVERSATION

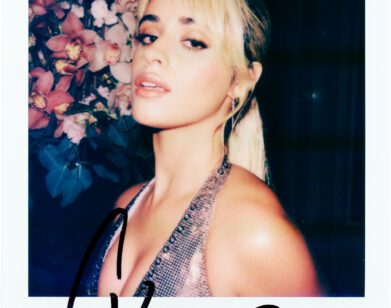

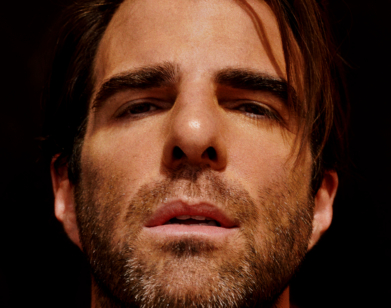

Ebon Moss-Bachrach Brings Sarah Paulson Into the Kitchen of The Bear

“I was early to the Ebon Moss-Bachrach celebration,” says Sarah Paulson. “I didn’t need The Bear to know what was great about you because I’d been a fan from the New York theater days.” On Zoom earlier this month, before the highly-anticipated drop of the show’s second season, Paulson extolled Moss-Bachrach’s self-effacing devotion to his characters, a quality on full display in the seventh episode “Forks,” a Moss-Bachrach showcase in which Carmy (Jeremy Allen White) sends his cousin Richie on a one-week residency at one of Chicago’s premiere fine dining establishments. Though Paulson got the chance to observe Moss-Bachrach’s gifts firsthand on The Bear set—she is one of a slew of high-profile guest stars in the new season, including Bob Odenkirk, Olivia Colman, and Jamie Lee Curtis—the pair worked together even more intimately on the forthcoming psychological horror film Dust, directed by Karrie Crouse and Will Joines. After cleaning up her dog’s puke (she had given him scraps of cauliflower pizza the night before), Paulson logged on to talk to Moss-Bachrach about how he chooses roles, being a cat dad, and why great art doesn’t actually require suffering.

———

EBON MOSS-BACHRACH: Hi, Sarah.

SARAH PAULSON: Hi. I just wanted you to know, Ebon, that I was just cleaning up dog vomit, and that was the delay. You should understand that, I know you have two children.

MOSS-BACHRACH: Yeah, I have two children. I haven’t cleaned up vomit for a while, though. Not their’s, anyway. Maybe a friend’s.

PAULSON: And the cat.

MOSS-BACHRACH: No, my cat’s perfect. He doesn’t puke. I don’t even think he shits. He’s just descended from heaven. Do your dogs throw up a lot, or did they eat something bad?

PAULSON: The truth is that on Sunday nights I tend to have a great meal that I get excited about and it often involves some sort of really shitty pizza. I know, great meal and shitty pizza sound a little incongruous. But it’s actually really thrilling for me, and I’m unable to not give my dogs bits of it when they beg. So I gave her some cauliflower crust pizza, Ebon, and I think perhaps it didn’t agree with her.

MOSS-BACHRACH: Cauliflower can make you pretty gassy.

PAULSON: I guess it can, but I would think she would be used to it by now.

MOSS-BACHRACH: I’m such a new cat dad and I’m still scared of alliums. They’re toxic for cats.

PAULSON: What the hell is an allium?

MOSS-BACHRACH: Anything in the garlic, onion, chives, scallion family. So I clean up after myself a lot more than I used to. When I’m cooking, I got a little hand vac.

PAULSON: Wait, did you have the hand vac pre-cat?

MOSS-BACHRACH: No. Historically, I’m not a hand vac kind of person.

PAULSON: That’s why I was intrigued.

MOSS-BACHRACH: But I understand wanting to spoil her. I gave my cat a little glass of goat milk today.

PAULSON: You’re like, “Here, come to the land of human living and enjoy a little goat milk from your cat dad. Love, Ebon.”

MOSS-BACHRACH: But honestly, I wanted to talk to you because the last time I saw you, you were handing out your phone number to everybody on set, but I’d known you longer than any of those people and I still don’t have it.

PAULSON: I don’t think I do have your phone number. I’ll just say this, I was early to the Ebon Moss-Bachrach celebration. I didn’t need The Bear to know what was great about you because I’d been a fan from the New York theater days. I was so desperate to work with you that—and I’d like credit for this—I suggested you for the movie that we ended up doing together last summer [Dust]. Everyone talks like it’s a foregone conclusion that you’ve always been the greatest, which it is, but I was there in the beginning.

MOSS-BACHRACH: I’m glad to hear it. It would’ve been nice to have known during some of those walks through the desert.

PAULSON: My question to you, given this undeniable shift in your work in the last couple of years, was there ever a hunger or upset about not getting to do exactly what you fantasized about doing? Or were you satisfied before this forward shift?

MOSS-BACHRACH: First of all, for so long, I was shy and didn’t want to be in the public sphere as much. I approached acting from the other side.

PAULSON: I think that’s why you were so compelling, was that there wasn’t a lot of, “Look at me.” It was more, “Pay attention to the person I’m inhabiting in this story.”

MOSS-BACHRACH: It just seemed like a lot. But you start to do more work and want better parts.

PAULSON: Right. It’s less about being celebrated and more about having the opportunity to sink your teeth into something that’s meaningful to you.

MOSS-BACHRACH: Exactly. And I got tired of not getting the part that I wanted. At a certain point, frustration is a good motivator. When I was younger, I was kind of blissful and oblivious and stoned, doing plays and playing around a little bit on movies and TV. It was very carefree, which I liked, but when I had kids and a family, that lack of responsibility started to feel irresponsible. It was infantilizing, and it was time to grow up and be responsible.

PAULSON: Once you came into taking responsibility to care for your family, did you ever find yourself having to say yes to something you didn’t want to do?

MOSS-BACHRACH: Oh my god, are you kidding me? It also meant preparing more and considering what might be a smart career move rather than just what I felt like doing at the time. When did you start feeling you needed to get a little bit more love for what you were doing?

PAULSON: Some conversation between me and a therapist would be necessary to pick it apart in a real way. But as an actor, I wanted to be paid attention to. In my home life, I didn’t have a ton of focus on myself, so there was an innocent impulse to want to be seen and taken seriously. I had a nagging thought that I could do something harder than what was being asked of me. But I was still working and making a living. I would get salads at Urth Cafe and be like, “Look, we bought this salad with acting.” I’m so interested in the part of you that doesn’t feel drawn in by being in the public sphere because I definitely wanted that.

MOSS-BACHRACH: That could’ve also been a fear of failure.

PAULSON: I was terrified to fail, too, but I still wanted it. Granted, this was pre-social media. I wasn’t pursuing what fame looks like now, but I wanted to be on the cover of American Theatre Magazine with all those cool folks. You know what I mean? If I didn’t have that anointed feeling, I felt like what I was doing wasn’t real, in some weird way.

MOSS-BACHRACH: I was always really good at not working, too. I don’t think I’m a competitive person.

PAULSON: From afar, it always seemed like you were in it for a pure reason.

MOSS-BACHRACH: Definitely. I’m from New England, from Massachusetts. The self-loathing and feeling like I’m nobody special is baked into me good. So to even celebrate myself in this conversation is making me sweat a bit.

PAULSON: But now that I’ve gotten to work with you twice, I find you to be incredibly bold. I’ll never mark through something full-out in a rehearsal. I’m too afraid. I have to wait for the proverbial curtain to come up, call action, turn the camera on me, and I’m no longer thinking about who’s watching me. I’m struck by your not giving a shit how you’re perceived. It was really a profound thing for me to witness.

MOSS-BACHRACH: Okay, is there a question in there?

PAULSON: No, there isn’t.

MOSS-BACHRACH: You’re just trying to make me feel uncomfortable. Man, I was so struck by the physical environment of this movie in the Dust Bowl in Oklahoma with all the wind. It was so much about light and dirt and darkness to me that I was genuinely trying to just do whatever our DP, Zoë [White], thought would look good. And that’s something I never do. I’m always like, “I’m going to tell the fucking truth. You guys figure out how to shoot it the best.” But I was completely in service of the visual storytelling there.

PAULSON: So it’s not how you always work.

MOSS-BACHRACH: No, but I found out later that you were working with Julia [Crockett] on movement stuff, so I was like, “Okay, I’m not the only one trying to figure some stuff out here.”

PAULSON: It’s true that sometimes the environment of a set can do most of the work for you if you allow it to. Even when I came into the world of The Bear, it was a little hard because I’m such a fan. I was still kind of disappointed I couldn’t be at the actual restaurant, at The Beef. Everyone came to say hi and it was so cool, but I know that I would’ve felt something different had I been in the restaurant.

MOSS-BACHRACH: I’ll tell you, you would’ve felt dirty if you were in the restaurant.

PAULSON: I would’ve loved it. I wanted to be just a dirty Bear person. Did you get offered that role?

MOSS-BACHRACH: I made a tape. This was all during Covid, and I was in England working on something. A couple weeks later I did a Zoom chemistry read with Jeremy [Allen White], and then I didn’t hear anything for a month and mourned it. And then after I had lived out the sadness, they called.

PAULSON: You mourned it because you knew.

MOSS-BACHRACH: I really, really wanted to do it. The writing was so good, the characters were so vivid, and oftentimes so much of the work is to fill in the blanks. I love that work. But this time, there’s fuel here and I can just start playing.

PAULSON: That’s a testament to the value of the writer. It’s an interesting thing when the writing is so good that it just carries you. When you get a script and it’s just neither here nor there, and there’s nothing clear-cut about the character at all, it’s up to you to bring something to it. I agree with you, sometimes I like that work. Other times I feel like I could do 30 different things and I would like to know what would serve the story best. Once you have a little taste of how good it can be when the words levitate you from point A to point B, it makes it hard.

MOSS-BACHRACH: It makes it harder to agree to something that maybe could be good if everything comes together. The first thing I did after The Bear was Dust, but that had an openness to the character. I listened to music and looked at all kinds of photographs and went to all these different places I wouldn’t normally go for inspiration. That’s so fulfilling. That’s a job of writing that I’m happy to do. But the writing in The Bear was inspiring in a much different way.

PAULSON: Did you have any idea that people were going to respond to it this way?

MOSS-BACHRACH: I loved the process of making it, and then when I watched it and thought it was really good, I was like, “Oh, it’s not going to do well.” I thought my taste was so weird that I’m out of sync with what people like. That’s why I don’t like to watch stuff because most of the time it’s a bummer. It just takes away from enjoying my experience on set, and sometimes I just want to leave it there. But this one I watched because I did feel so passionate about it, and the response to it was shocking. I was out of the country last summer on vacation. I just started getting text messages from the cast, like, “This is crazy. What’s going on?”

PAULSON: Oh my god.

MOSS-BACHRACH: It was so cool and exciting. I’ve never been part of something like that before. But now I feel stressed because we have expectations. There are a lot of eyes on it. It kind of dovetails with what I was saying earlier about a fear of failure. If there’s no one looking at you, then there’s no one to say, “Oof, you could’ve done a better job.”

PAULSON: Right. What do you think is the fundamental difference between seasons one and two, besides plot-wise. Was there any energetic difference on set? Did you guys talk about this expectation?

MOSS-BACHRACH: We didn’t talk about the expectation, but we did very much talk about the differences between the seasons, how season one was like the dying wail and this one is more forming this restaurant. But it’s much more introspective. Speaking for just the journey that Richie is on, he’s lost that fight of wanting to keep a neighborhood institution. It’s very unclear what his role is in this new place. It’s unclear what his role was in the old place, let alone in this new version. So he’s really spun out and looking for purpose. He’s also, like, 45. That’s an age, you know?

PAULSON: That’s definitely an age. Have you seen the second season in full?

MOSS-BACHRACH: They sent it to us last week, and I was watching the episode that you’re in. I’m halfway through that episode. You’re great.

PAULSON: Shut up, oh my god. Just kidding. I also can’t believe how fast you guys shoot. Can you corroborate this for me? That wasn’t unique to that episode, right? I was in the makeup trailer, and Gillian [Jacobs] was like, “Just know they go really fast,” And you think, “Oh, sure, okay.” But I come from a world where we’re talking 18 and 19-hour days sometimes.

MOSS-BACHRACH: Wow.

PAULSON: So this was otherworldly to me in how efficient everything was. And Bob Odenkirk, when we were all done, was like, “This is one of the greatest sets I’ve ever been on.” So you can be on a set where people move quickly and there’s still camaraderie and a sense of family. It was really palpable, I was like, “Boy, I’d like to live here.”

MOSS-BACHRACH: But those go hand in hand. We shoot fast and we do 10-hour days, I’d say. A lot of that camaraderie is because everyone’s going home and seeing their family and no one’s driving home at 2:00 in the morning, day after day after day.

PAULSON: And falling asleep.

MOSS-BACHRACH: Falling asleep and not feeling taken care of. There is a mode of working that I certainly had nothing to do with. They’re just like, “We’re going to respect people and treat them well,” and everyone is really happy to be there. It shouldn’t be a shock, but—

PAULSON: No, it shouldn’t be a shock. We’ve all just gotten indoctrinated into the belief that you have to suffer in order to make it good.

MOSS-BACHRACH: Totally.

PAULSON: I have let go of a lot of that. But some of that maybe comes with hitting that 45 age. I’ve been so used to working in a particular way that this was so other to me, knowing what I know about what the end product is. It was a wake-up call that we can still make good things that are meaningful and about family and friendship.” It’s amazing how little it happens.

MOSS-BACHRACH: To be fair, you’re in the hair and makeup chair, a lot, right? You’re putting on crazy disguises and wigs.

PAULSON: Once you hit that age, it’s a lot of spackle and paint, Ebon.

MOSS-BACHRACH: Oh, yeah. You’re doing 90 minutes with the black tea bags.

PAULSON: So true.

MOSS-BACHRACH: It’s a 25-minute-long show, so you can’t do that for everything. But it’s something to shoot for. Who’s ready to work when they’re totally exhausted all the time? It’s terrible.

PAULSON: Correct. This is an opportunity to reflect human experiences back to other human beings, and that is what the work is to me. So it’s like, all the Sturm und Drang trying to get everybody to turn themselves into a pretzel and work to the brink of their capacity is unnecessary. We are incredibly lucky to be able to do something that we’re passionate about that actually should be fun to a degree and doesn’t have to be really arduous.

MOSS-BACHRACH: Yeah. When I was younger I was putting insane amounts of pressure on myself to connect to some sort of, I don’t know, godly truth. And then realizing, I’m going to fail. I’m going to fall on my face. I recently read something Willem Dafoe said where he tries to fail. Let’s try one way, let me see how wrong I can be. Allowing yourself to not be the best creates relaxation. You can’t make art from a white-knuckled, coiled place.

PAULSON: That’s right.

MOSS-BACHRACH: Once you relax a bit, then you can surprise yourself. That’s so valuable for me. I mean, athletes can’t play tight. Or musicians. It probably also came from getting older and world-weary.

PAULSON: Did that awareness come along with the success that you were starting to experience in new ways?

MOSS-BACHRACH: Yeah. All of a sudden my experience of making things is so much better, and I think my work improved.

PAULSON: Because you weren’t holding onto it so tightly.

MOSS-BACHRACH: I wasn’t trying to win a fucking award. Which was never even a possibility anyway. Or I stopped trying to be Marlon Brando.

PAULSON: Well, the possibility is happening now. All the statues for you, my friend. I’d like you to have a whole passel of them, personally. You deserve them.

MOSS-BACHRACH: Thanks.

PAULSON: I know they don’t matter, but you can use them as a doorstop. You could use it for all kinds of things. Cat toys could be attached to it. You could improve your cat-dadness.

MOSS-BACHRACH: I could lean a hand vac against it. No disrespect.

PAULSON: No disrespect to it. It’s just you can do a lot with them, I think.

MOSS-BACHRACH: I feel like we’ve never really gotten to talk like this.

PAULSON: Because I’m always feeling like I’m just hanging on for dear life. Julia Crockett, who you mentioned earlier—sometimes she’d be watching the monitor and she’s like, “I don’t think you took a single breath during that entire take.” Sometimes I need to be reminded that I’m playing a living, breathing person and I can breathe every once in a while.

MOSS-BACHRACH: It’s not easy.

PAULSON: It’s not easy. Why haven’t you given me your phone number?

MOSS-BACHRACH: I was waiting for you to ask.

PAULSON: You’re waiting for the official invitation? I’m going to send you my business card. DM my publicist, and then I’ll DM your publicist back, and then give you my phone number that way.

MOSS-BACHRACH: Oh, god. I’m going to take a nap.

PAULSON: Well, I really adore you and I think you’re the fucking greatest in all respects.

MOSS-BACHRACH: Thank you, Sarah. Right back at you. You’re the best. I’ll talk to you later.

PAULSON: All right, my friend. Talk to you later.