IN CONVERSATION

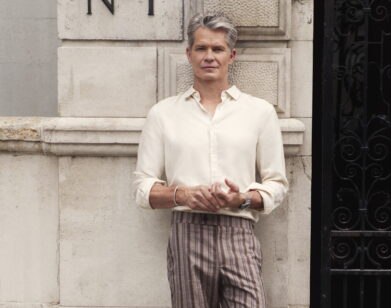

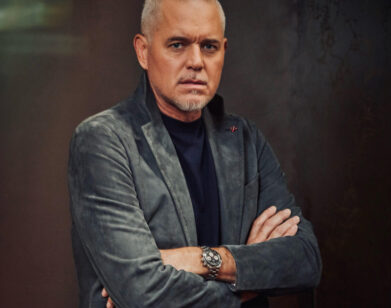

Boots Riley and Tze Chun on Hollywood Diplomacy and Writer’s Room Morale

When asked about the critical reception to his new series I’m a Virgo, Boots Riley responded, “There’s a few people hating it, so that feels good.” The 52-year-old musician, activist, and director has never been afraid to take risks that may jeopardize his commercial appeal. His directorial debut, Sorry to Bother You, was a surrealist, anti-capitalist comedy following a Black telemarketer in Oakland who begins faking a white person’s voice and is subsequently sucked into an outlandish corporate conspiracy. Like that film, I’m a Virgo uses magical realism to advance its thesis about race and poverty in America. Its protagonist is Cootie, a 13-foot-tall Black teenage living in Oakland who, when we meet him, is determined to break out of his sheltered existence. He lives with his adoptive parents, who’ve kept him in hiding, where he’s made to read for 10 hours a day. “People are always afraid, and you’re a 13-foot-tall Black man,” explains an acquaintance. But his efforts to transcend these confines and embrace the real world put him at odds with his former idol, a vigilante committed to upholding the status quo. Shortly after the show premiered, Riley hopped on a call with the writer-producer Tze Chun, the series’ co-showrunner, to chat about the importance of morale in a writer’s room, preserving your integrity in Hollywood, and how they fought, together, to retain Riley’s bold, allegorical vision for I’m a Virgo.

———

BOOTS RILEY: What’s up, Tze?

TZE CHUN: Hey, Boots.

CHUN: I’ve been traveling, so I haven’t talked to you. How are you feeling now that the show’s been out for a couple weeks?

RILEY: It’s weird because we’ve been working on this for years. I had the idea at the end of 2018, but I started writing the pilot at the beginning of 2019. And I’m used to stuff that’s a little more polarizing than this. I have this thing in my gut where if there’s not enough people hating it, I’m like, “Did I do something wrong?” And there’s a few people hating it, so that feels good.

CHUN: You worked on [I’m a Virgo] for four-and-a-half years before it came out. In terms of delayed gratification and feedback, that’s a long time.

RILEY: Yeah, that’s a long time. With music, you make a thing, put it out there, people like it or they don’t like it, and then you’re like, “Fuck, okay, let me make this other thing.” But with this cycle being so long, I was ready for the next thing.

CHUN: That was one of the things that I found so hard about indie film. If you’re lucky, you get to make a movie every four years. And then what if people don’t like it? What if you do a bad job? I did a movie that was well-received and then spent three or four years on a movie that wasn’t. So I wanted to get into network TV, because I was like, “Well at least I’ll be doing 22 episodes a year, working all the time, getting better at writing.”

RILEY: Do you get stuck reading people’s reactions on social media like I do?

CHUN: When I first started, I did. I remember getting a mixed review for my Sundance movie, Children of Invention. I was 29-years-old and it just destroyed my week. But nowadays I’m just proud of all the work that we did on I’m a Virgo and Gremlins [Chun’s children’s TV series]. And the nice thing is that the reviews have been extremely positive for both shows. What I love about I’m a Virgo is all this great comic book stuff that you brought to it, like the deconstructed hero stuff. You’re not leading with the comic book side of things, but that’s definitely a part of it.

RILEY: To me, a comic book story is not the same as a superhero story. What do you think is the difference?

CHUN: Well, comic books are a medium and a superhero story is a genre. First off, I still can’t believe that I live in a time where they [superhero comics] became cool. What I love about the medium is that it’s not just that one genre, even though superheroes are the predominant genre in terms of sales. There’s so much creative stuff happening, and it’s a different way of telling a story. And one of the things that I really love about I’m a Virgo is that we move from live action to animated sequences to things that are really surreal. And Mystery Meat [a media company that contributed animation for I’m a Virgo] did unbelievable work.

RILEY: Their studio is in the basement of a dentist’s office right here in Pearl Hill in Oakland. And in this little space, you get this giant universe. That’s one thing I like about animation: it feels closer to music. Those two guys can be like, “Oh, we had this idea, and here it is, we did it last night.” And you can do that with music, but not so much with film.

CHUN: I think because both of us come from indie film, we thought we could have more time to be creative if we could scale stuff down a little bit. And I feel like Mystery Meat was one of the only places where we succeeded in doing that. Everything they did was so handmade.

RILEY: I think in big budget films and in TV, there are people involved in setting the budgets that don’t actually make [films or series]. So it’s hard to convince people that you can do grandiose things with a certain budget. So we had to wage a fight.

CHUN: That was certainly a fight and a wake-up call. The pilot came in through my manager, and he was like, “Hey, do you like Boots Riley?” And I was like, “Yeah, I loved Sorry to Bother You.” And he’s like, “He has a show about a 19-year-old, 13-foot-tall Black man growing up in Oakland. Do you want to read the pilot?” And I was like, “Sure, I’ll read that.” It was my favorite pilot I’ve read in like, five, seven years. And in that first meeting what was so cool was that you showed me the way that you were going to shoot [the show], practically. And as surreal as the show is, having it out in the world feels even more surreal. And I think a lot of people have watched it that I wouldn’t have expected to.

RILEY: It came out a lot sweeter than I think we were predicting, and that had to do with the performances. It wasn’t until we had a rough edit that I was like, “Oh man, this is going to touch people on a different level.” That’s a difference between film and music. Sometimes with writing film, you know you’re putting emotion into something, but it’s still kind of cold and calculated. But you might write a song and be crying while you’re singing it and recording it, because you are feeling it in the moment. I haven’t heard about that happening so much while someone’s writing a scene and putting in dialogue descriptions.

CHUN: When I was writing my first feature, Children of Invention, I started to realize that I have to feel something very heavily while I’m writing it in order for the audience to feel even a fraction of what I want them to feel. The film is semi-autobiographical. It’s about me and my sister and being raised by a single mom. I thought I was writing a light comedy, and then watching it again it’s like the saddest movie I’ll ever make, hopefully. But because I had lived inside of it, I didn’t feel that until it all came together. People were watching [the film] and saying, “Oh, it’s really sad what’s happening to these kids.” Because I’d gone through it, I was just like, “Yeah wasn’t it funny that time that thing happened?”

RILEY: Yeah, if you’ve gone through it, you have your own experience, but you’re being vulnerable and letting the audience interpret it. We knew that folks were going to be sad about the loss of one of the characters—

CHUN: Yeah, especially ‘cause Scat doesn’t have a ton of scenes before he dies. But also, in terms of casting, the cast members didn’t really know each other before they came to set and they became good friends. I think you could really feel that. A lot of times, if you’re writing a TV show, you’re like, “Okay, we want to differentiate these characters. Who are each one of these characters?” But I really like that we did something different. You introduce them all together and then all of a sudden the audience is living in that friendship.

RILEY: With I’m a Virgo, some of the stuff that we wrote fell away, because the actors can be in a room together and just have a reaction that just says it all, right? And that was a hard thing to figure out. We had a lot of chemistry reads to figure out who could be who, and we changed the story a little bit, especially when Brett [Gray] came on. He changed the character just by being him. Some of it is just letting experimentation happen while the camera’s on.

CHUN: The production was intense, obviously. I didn’t really recover until seven or eight months after. And you directed every episode. Somebody asked me, “What was it like for Boots to direct every episode?” It was hard watching somebody get more tired every day for two years. But it was really important to me to preserve the things that were important to you, the things that you felt were against the grain. And there’s a typical process when you write a half-hour show. You break it into three acts. One of the things I’m glad we did is that we just looked at the episodes alone and didn’t break them into acts. We just broke up each episode according to the way that the story wanted to be told. And it’s tough, because you’re walking into a system that’s been around for 70 years. The DNA of a sitcom remains the same. But I was glad that we pulled some of that stuff out.

RILEY: When I was doing Sorry to Bother You, I was lucky that whoever I was working with didn’t think I knew how to do all that stuff. So we could do it however we wanted. I had obviously never been in a writer’s room. But you were very instrumental in making me be like, “Okay, well if Tze says we can do it this way, then it’s a real possibility. He’s been in writer’s rooms before, he knows how it goes.”

CHUN: I’ve been in writer’s rooms where you’re there for eight, nine hours a day. And you’re doing 22 episodes a year. I remember the second year I was doing network TV, I looked across the table and I was like “I’ve looked at this person’s face more than I’ve looked at anything in my entire life. I know every mole on his face.” And I just think that time spent and productivity are two different things. Sometimes something feels good in the room, but you need a little bit of time off to reexamine it. And I wanted you to have that time.

RILEY: Sometimes with a piece of art, you can spend so much time on it that you don’t like it anymore. That’s going to happen at some point with everything. You know what’s good about it intellectually, but you’re not excited about it anymore. You go through this period of being bored with it. But I think because of the way you structured the room, you achieved this great balance. There were times where we’d be like, “Okay, we’ve talked about this enough.” And then we had that time by ourselves to be inventive and make ourselves excited about [the show] again. I feel like when you were leading the room, you were more like a cool babysitter as opposed to an authoritative stepfather. Like, “Oh, we get to have macaroni and cheese and then we’re going to watch R-rated movies.” But with enough authority so that nobody’s killing themselves.

CHUN: When I first moved out to L.A., I sold a pilot and it didn’t go forward. And I remember thinking, “I’ve got to be patient and learn this process and see how this is done.” And then in five years, I’d done 100 episodes of TV. And the biggest lesson I learned from that time period was that the most precious resource in the writer’s room is morale. Everything else is secondary to that. Writing is too hard of a thing to do every day if you’re dreading it. And like you were saying, what was really nice was that sometimes we’d say “We’ve figured this out, the rest of it is going to come. We don’t have to beat a dead horse.” But we also made it so that you could go off and come back in with a cool, big idea. I remember the day you came in and you were like, “There is an animated show within the show, and it’s the best written show on television, and it should feel like F. Scott Fitzgerald wrote it.” When you came in with one of those big ideas it’d be like, “Let’s get into it. Let’s talk about it enough so that we can continue being excited about it. And if we want to take a break and talk about it tomorrow, we can do that.” Those days were really, really special.

RILEY: The room was the first audience for those ideas. It’s interesting because we cut about 60% of that out. But there are some really good things that have happened like that. In so many songs throughout history there’s something fucked up that happened with an amp that everybody loves. Or somebody didn’t show up, and David Bowie was down the hall so he came and sang the part. So I will say that cutting so much did lead to leaning on other things, and that has made the show what it is.

CHUN: It’s nice to hear you say that, just ’cause at the time it was so deeply traumatizing. We cut 80 [days of shooting] to 55 [days]. You know how I had that piece of paper where I was trading days and hours and half-days? It’s like that meme of Charlie Day pointing to the board with all the yarn and everything.

RILEY: I also think that’s part of the writing of a show. Which things do you cut? Which things do you save? Like, “Why are we saving this fart argument?”

CHUN: That was not from me. I was a proponent of the fart argument.

RILEY: Yeah. But like, “We’re cutting this battle scene so we can have this fart argument? What are you doing?” ut the point is that we fought for the creativity of the show. And like you said, you were a proponent of keeping the weird stuff.

CHUN: What I said to you in the last couple weeks of shooting is still true. I really admire your ability to be stubborn and fight for some of these things, because I probably would’ve folded after two or three battles. And on the flip side, there are things that I really care about, and I know I certainly have fought for things on the shows I’ve created. I’ve learned that if you believe in something, you just have to make it really fucking hard for somebody to convince you otherwise until they’re exhausted.” And a lot of times it really worked.

RILEY: I definitely had to have consultations with my agents and stuff like that. There was somebody that said to me, “You don’t want to seem unreasonable.” And then I realized that if I seemed too reasonable, then there could be a calculation of what I’d be down to do or not. And I’ve made a lot of bad decisions as a musician, too. The label would say, “You know, we really thought about it, and we think you should have choruses on this album.” And I’d be like, “Choruses? You think I’m a sellout? Hell no.” Looking back at it, these were bad decisions that I made in reaction to someone trying to have influence, even when it was good. And so I do try to mitigate that. But you were really helpful in that whole process. There were people freaking out, and you knew how to translate some things for them in a way that calmed them down a bit.

CHUN: This is just my perspective, but the industry has a way of changing you. And it’s never something that happens all at once, like a Faustian bargain. It’s a little foothold here and there, and then you start to change, little by little, and you’re starting to give up things that you once found important. You start to forget not just what you’re doing, but why you’re doing it. And something that I have made my goal is, “How do you become successful in a business while staying who you are?” And it’s a really hard thing sometimes. You have to pick your core principles. Like, because of the way that I grew up, I never want anybody to be afraid of me. There’s 1,000 ways to get what you want, but making somebody afraid of you is not something that I’m willing to do.

RILEY: I’ve definitely heard a lot of stories from other sets where people didn’t follow that.

CHUN: It’s something that I’ve grappled with a lot. You have to set rules so that you don’t abandon the things that made you start in the first place. Because if you abandon the things that made you start this in the first place, then by the time you’ve become successful you won’t want that career anymore because it’s not yours. Just to completely bring the vibe down…

RILEY: No, no. I think that the way things are structured is part of what leads people to taking that away, little by little. [But] I think the more writer or creator-driven things there are, things that aren’t coming from a producer or studio saying, “we need this,” you’ll have people fighting in those ways.