TOSS UP

Got Election Anxiety? Nate Silver Can’t Save You.

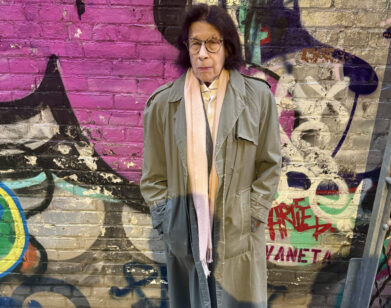

You might think it’s a fairly stressful time to be Nate Silver. With the presidential election less than a week away, one imagines the writer, statistician, and founder of the polling website FiveThirtyEight seated at his computer, crunching numbers and running election simulations as pangs of 2016-induced trauma come back in waves. Silver, you’ll recall, gave Donald Trump a 28.6% chance of beating Hillary Clinton—considerably higher than the consensus among pollsters, but low enough that he nevertheless incurred what seems in hindsight to be a disproportionate amount of rancor from beleaguered democrats who were ill-prepared for the possibility of Trump’s victory.

But when I spoke to Silver earlier this week, he’d reached a kind of peace with his status as the country’s foremost polling expert and de facto fall guy. Silver—a former poker player who now sports a gray-ish beard and a Detroit Tigers baseball cap—speaks the language of probability, not predictions. “People will be equally mad at me either way,” he explained, “so I’m less stressed than usual about that.” In 2023, Silver stepped down from FiveThirtyEight and began publishing more regularly on Silver Bulletin, his Substack blog. There, he runs his own election forecasting model, which will tell you what he more or less delineated in a guest editorial for The New York Times opinion page last week: the election is a toss up, with seven swing states all polling within one or two percentage points. And while Silver’s gut says Trump, he doesn’t put too much stock in intuition. The day after Trump and his supporters descended on Madison Square Garden in an inflammatory spectacle of grievance that Silver could overhear from his apartment a few blocks south, he talked to me about Americans’ fraught relationship to polling and Silicon Valley’s embrace of the 45th president.

———

JAKE NEVINS: Hey there, Nate. How are you doing?

NATE SILVER: I’m good. How are you?

NEVINS: I’m good. Thanks for taking the time to talk. I know you’re a busy guy and this is a busy week.

SILVER: Well, it kind of slows down the week before the election and people stop scheduling as much and just get nervous.

NEVINS: Are you nervous? How do you handle pre-election anxiety?

SILVER: I have a couple beers at night. I don’t know. In some ways, because the forecast is so close to 50/50, it’s kind of like no one’s really saying anything. People will be equally mad at me either way, so I’m less stressed than usual about that. Also, you get more life experience and you’re kind of like, “Ah, fuck it.” What happens will happen. So I’m okay.

NEVINS: You’ve weathered this storm before.

SILVER: I’ve been through a couple, for sure.

NEVINS: Well, let’s get into it. What compelled you to write that Times op-ed earlier this week?

SILVER: Well, my editor reached out and he’s like, “Do you have something for us?” I’m like, “I could write something on the different ways that polling could go wrong.” I’m revealing more of my process than I should, but I think he’ll be fine with it. Anyway, I filed a piece and he’s like, “This is pretty good, but we need some more interesting wrinkles. What if you say what your gut feeling is about the race?” I’m like, “My whole thing is, I’m me. I don’t really think that my gut’s very valuable in this context.” In fact, it’s the one place where you should probably just ignore your gut, but we can kind of make that the framing of the story: “why you shouldn’t trust your gut.” And to make it more interesting, I’ll reveal what my gut is and say why I don’t think it means anything, right? Of course, half the news outlets pick this up. I’m like, “My gut would pick Trump, but the reasons for that are primarily because of the information environment and how the news cycle has gotten very Trumpy. And emotionally, people remember 2016, so they’re hedging a little bit.” But instead, people took that as a prediction that Trump’s going to win. But it’s a forecast, not a prediction. It’s 54% Trump. It’s basically a coin flip. But people overrate their gut so much that even in a piece where you say in the headline, “Don’t trust your gut,” that was the takeaway. I was very aware that this would probably cause confusion. But I was like, “Fuck it, it’s an interesting story.” It’s a little bit daring for someone to say, “Here’s my instinct, but you shouldn’t believe it.” It requires some higher level thinking that might be absent 12 days before an election. But yeah, that’s the origin of it.

NEVINS: Well, you took the words out of my mouth. I found it kind of amusing and I guess discouraging that in a piece where you demonstrate all the ways in which the election is truly a toss-up, most news outlets picked it up as, “Silver says Trump.” I imagine you’re just used that kind of thing by now, right?

SILVER: At this point I just kind of say, “Fuck it.” I mean, I have a newsletter that’s popular and people who know me know me. There are a lot of people who A, act in bad faith, and B, are emotionally addled by an election campaign, or C, really get the math and probabilities. I’ve just decided I’m going to do the best writing that I can and run the best model that I can. I’m in a pretty good position to deal with people’s anger.

NEVINS: That brings me to your new book, On the Edge. In the introduction you write, “Forecasts are a sign of humility, not hubris.” But people seemed to get quite the opposite impression in the wake of the 2016 election. I wonder what you make of Americans’ relationship to the whole enterprise of polling writ large.

SILVER: Look, I don’t know why these probabilistic forecasts are so insanely popular. I mean, I had a background in poker and forecasting and gambling and things like that, and that’s how you talk about probabilities if you’re an adult in the gambling world. You put a probability on it instead of this fuzzy language, and that allows you to be more precise. The fact that we had Trump at 29%, or 30% if you want to round up, and the consensus was 15% or lower than that, then in my way of thinking from the gambling world, that means you have a good bet to make on Trump. If your odds are twice what the consensus is, then that’s a high expected value wager. I’ve never fit into the politics world. I don’t talk to political operatives. I don’t even talk to pollsters. I’m providing a pure outside view. I think that serves as an antidote to the obsession with insider information, which is useful for many, many, many things but doesn’t really tell you anything about who’s going to win.

NEVINS: Right. I don’t necessarily want to ask you to draw major conclusions about the American populace based on the reporting you did for this book, since it concerns a pretty narrow group of people inclined to think much like yourself, but I was intrigued by this notion that the American appetite for risk tolerance is greater post-COVID. Do you see that playing out in this election cycle?

SILVER: It is interesting. I guess that in 2016 people were like, “Ah, we’re bored. Fuck it. Let’s elect Trump.” And then in 2020, people were much more worried about the pandemic and the various economic crises that it triggered and adopted more of a risk-averse mentality. There might be something there. I mean, Trump is clearly a riskier choice. I’m not trying to be euphemistic about that. Even if you don’t think it will be our last election, there are tail risks that things could get pretty bad. I don’t know that I want to go about quantifying them, but it’s probably a material factor. There’s a little bit of YOLO, I think, to Trump, and you see that more explicitly with the fact that he has much more vocal support in the communities of Silicon Valley and Wall Street and crypto people, and he’s kind of reciprocating to some degree. It kind of makes sense to me. When I wrote the book, I hypothesized that what I call the “river” and the “village” are kind of natural rivals; the village is more blue and the river is traditionally more purple, or even purple-blue, but obviously you have this vanguard that’s very, very Trumpy. But I didn’t expect the explicit clashes that you’re seeing. I mean, until there was the Bill Ackman versus the Harvard president thing, it was more theoretical. Now, you really see the 1% is at war with the other 1%.

NEVINS: Quite a few titans of Silicon Valley appeared at the Madison Square Garden rally yesterday, including Elon Musk. You noted in your blog post yesterday how some comedian I’d never heard of, Tony Hinchcliffe—Google searches for his name are exceeding those of Taylor Swift after the pretty inflammatory remarks he made about Puerto Rico. Do you think that sort of MAGA on steroids spectacle was a miscalculation for the Trump campaign so close to election day?

SILVER: Maybe. I mean, first of all, every time the liberal media says this is going to end Trump, it doesn’t. But when I was looking at the Google search data I was like, “Oh, there might actually be something here. This is starting to get pretty big numbers.” The crassness of the remarks, there’s no sympathetic interpretation of it, and I think that was the only thing that really resonated and catered to certain negative stereotypes about who Trump is and who his supporters are. Again, I’m literally proximate to it. I mean, I can see it from my house, so maybe I’m overweighting it a little bit, but it seems like at least this gives Harris something to close on, which she’d been kind of lacking. Trump had a good couple of weeks in the polls, but maybe there’s time for one more swing in momentum. But I don’t know.

NEVINS: I think there’s this idea, and it’s perhaps more ambient than it is empirical, that there’s less of a stigma now than in 2016 or 2020 to being outspoken in your support of Trump. To my mind, this doesn’t necessarily imply that there’s this new contingent of Trump voters; these people might have voted for him in both of those elections and simply not been vocal about it. But I am curious what you make of this notion.

SILVER: I think there’s a weird bias here. According to the polls, Trump is set to gain a lot of ground in New York City specifically. Because so much media is in New York, if you go from 20% to 30% of New Yorkers voting for Trump, then that’s pretty apparent, right? So you actually will notice more people who are vocal about it. And certainly in 2020, Twitter was kind of in peak progressive mode where conservatives felt hounded off. So now, the fact that this stuff is so much more in your face in different ways makes the experience different. I think people are not used to that, and maybe it’s partly why the momentum’s been favorable for Trump. But it’s certainly a different feeling. It’s no longer like, “Oh, there’s this hidden group of Trump supporters that we can’t capture.” It’s more a feeling of like, “Man, there are more of these people than I thought,” so people are more prepared for the verdict. At the same time, we also see more support for Trump among young Black men and young Latino men, which might not make it into the mainstream media conversation as much.

NEVINS: You talk about this in your Times op-ed. You wrote, “Polls are increasingly like mini models with pollsters facing many decision points about how to translate non-representative world data.” The idea being that the shockwaves from 2016 might be causing some kind of overcorrection amongst pollsters this time around. Am I understanding that correctly?

SILVER: Yeah. Look, I think pollsters don’t trust their raw data very much and are terrified. I mean, just the number of polls that are Trump plus-one, Trump plus-one, Harris plus-one, tie, tie, Harris plus-two—that’s not a natural statistical phenomenon. These margins of error are actually pretty wide. With the exception of maybe The New York Times, who have actually published some bolder results, it’s really just a matter of the polling industry. They’re just kind of sitting out the election in some ways and saying, “We give up on this one, it’s 50/50, we’ll see who wins.”

NEVINS: In your state-by-state model this morning, you identified seven swing states and noted that you’re running 40,000 simulations a day. What does that even look like? I think people might be curious to know what actually constitutes a day in the life of Nate Silver, sitting at his computer with his baseball cap on.

SILVER: The simulation itself does not really take that much time. I have Eli McCown-Dawson, my assistant co-worker, make sure that we have all the polls, and then I basically just press a go button and come back in 15 minutes and the model is done. It could probably be five or 10 minutes if I were a better programmer.

NEVINS: 40,000 simulations run in those 15 minutes?

SILVER: Yeah. I guess this gets kind of very technical, but we’re trying to figure out all the different ways that the polls could go wrong. In some simulations, Trump really beats his polls among Hispanic voters, and in others there might be big swings in the Jewish vote or the Arab-American vote or things like that that have logical electoral reasons for potentially happening. Then it kind of runs through all those, but it doesn’t take that long. I mean, with a faster computer and better coding, you could probably do it in five minutes.

NEVINS: Did you read this op-ed in The Nation the other day that sort of makes a strong case against publishing polls late in election season?

SILVER: I have not read it, no.

NEVINS: I’m going to read you a portion of it, ‘cause I’m curious what you make of it. But this is the logline: “With the alleged scientific and impartial effort to track public opinion and prospective voting behavior honeycombed with these kinds of perverse incentives, it’s long past time to ask what polling is really for. As a set of empirical assumptions about past patterns of voting behavior, it isn’t much use as a forecasting tool, as the last several election cycles have shown—-and that’s especially the case in a moment like ours, when many of the basic assumptions and ideological precepts that have long governed politics are up for grabs. Finally, as a guide to voting behavior, polling imparts very little useful information. Surveys of undecided voters are little more than glorified guesswork, as are the efforts to plot out the actions of “likely voters”—a category of diminishing utility as younger, low-propensity, and first-time voters exert greater influence than the mythic figure of the purse-lipped undecided voter. Polling has served some useful purposes in highlighting changing voter concerns, but largely in ex post facto focus groups. Again, as a form of prophecy or divination—which is what polling becomes in standard horse-race coverage—it seems not much better than a coin toss.” I’ll stop there.

SILVER: Well, let’s remember that the reason news organizations have spent a lot on polling to begin with—I mean, the poll The New York Times is doing where they’re surveying 2,500 respondents in a national poll when response rates are 5% or whatever, it’s not cheap—is that you actually do not want elites like me or the people at The Nation to infer based on their narrow worldview what people think. You want to actually give people a say. Now, obviously pollsters go through this dance where they say, “Our results are just a snapshot, they’re not meant to be predictive,” when clearly they’re happy to take credit when they have a good election. So I think the critique’s a little bit precious. I mean, I think that misunderstands the nature of news and it misunderstands human nature, too. People want to know what’s going to happen next. In this election, the polls don’t really inform you of that because it’s 50/50, more or less. Sometimes that can inform decisions. I have a friend in the UK who is not a Trump fan and is deciding whether or not to extend her visa. And if it’s 50/50, she might feel differently than if Harris were at 90%. Anyway, I think that making well-grounded predictions and forecasts is one of the oldest human activities and I think people shouldn’t be shamed for doing it or for being curious about it.

NEVINS: Right. It’s a supply-and-demand issue, no? There’s a real hunger for it. I’m a big football fan, for instance, and every week I have this truly feral urge to take in predictions about how the Ravens are going to do on Sunday even though I’ve long ago disabused myself of the notion that these people have any kind of insider knowledge. But as long as there’s an appetite for it, someone will be there to tell me if a given receiver is going to get more than 70 yards, or whatever.

SILVER: Look at the newsletter; about half the traffic is from the forecast model and the other half is from the articles that we write. There is a lot of context that people are interested in, and it’s a way to explore a lot of topics. I remember the party I went to in Brooklyn when [the election] was called for Biden. I’m like, “Okay, we’ve turned a page and we’re kind of emerging from the pandemic and whatever else.” Then lo and behold, four years later, he’s back, unless the polls are way off and Harris wins in a landslide, which is just not very likely. Understanding why that is is pretty important. If you’re not looking at the fact that he’s gaining ground among Black voters, among younger voters—those are questions that I think are worth asking. If you go back and read The New York Times or Washington Post coverage from the 1984 or 1996 elections, it’s very “boys on the bus.” It’s laden with stereotypes. So I think political coverage has gotten better as it’s gotten more numerate. And now, when The Times conducts a poll, they won’t treat it as though it’s the only poll in the universe, right? They’ll say, “This poll is a little weird, here’s what we think of that.” Maybe it’s an outlier. Maybe we’re doing something different and better or different and worse, but I think that literacy has made news coverage better on balance. Again, as far as I’m concerned, we don’t need as many polls as we have. But there’s definitely a demand for it that’s kind of absurd in some ways.

NEVINS: Right. Well, thanks for taking the time to talk to me. What are your plans for election night, by the way?

SILVER: We’ll have the newsletter going, probably have a model so that when one state gets called [we can note] how that affects the overall probability. I’ll also be doing some media, some consulting stuff. Election nights are always a kind of busy nightmare. I can never fully devote myself. They go fast, right? Like, “It’s 4:00 AM now, how long have I been up?”

NEVINS: It’ll be just like those long nights you used to spend at the poker table.

SILVER: Absolutely.