Yusuf Islam

For anyone who grew up in the ’60s or ’70s, the voice of Cat Stevens was a permanent and very beautiful part of the cultural landscape. A self-taught musician, born and raised in London, he’s written many pop standards—“The First Cut is the Deepest,” “Peace Train,” and “Miles from Nowhere,” to name a few—and from 1966, when he released his debut album, Matthew & Son, until 1979, he was one of the biggest pop stars in the world.

In December of 1977, Stevens converted to the Islamic faith, and shortly thereafter took the name Yusuf Islam. Two years later he turned his back on music entirely, and spent the next 28 years devoting himself to spiritual studies, raising his children, and philanthropic work. He’s received numerous awards for his efforts to promote world peace, and has given away quite a lot of money. Yusuf and his family now split their time between homes in London and Dubai.

In 2006, Yusuf returned to the public stage with an album of new songs, An Other Cup. The follow-up, Roadsinger (UMe), is out this month and includes a guest vocal by Alison Krauss, as well as two songs written for his forthcoming stage musical, Moonshadow, which debuts in London in July.

In conversation, Yusuf is sincere, modest, and witty, and he seems content with the life he has made for himself. It has been generally assumed that something about him changed when he converted to the Islamic faith, but, in fact, the music he’s making today addresses exactly the same themes that were central to the first chapter of his career: peace, the many wonders of the world we live in, and love.KRISTINE MCKENNA: What was the first record that you ever bought?

YUSUF ISLAM: “Baby Face” by Little Richard. I was fascinated by the way he did these curly things with his voice.

MCKENNA: I read somewhere that you were deeply affected by the film West Side Story [1961] when you saw it as a teenager. Is this true?

ISLAM: That’s true. I was interested in the lifestyle it showed because it was the archetypal life on the street, which has to do with one gang dominating another. I was spending most of my time on the street then, so that’s probably why it interested me.

MCKENNA: You were at the peak of your career during a period when rock stars were elevated to an extraordinarily exalted position in the culture. The music industry that fostered that phenomenon has dissolved and been replaced by the Internet, which has changed the relationship between musicians and their audience. Has the public perception of musicians changed?

ISLAM: It’s true that the Internet is an equalizer, and everybody can be a star now. Musicians are more touchable these days, and that’s a good thing. It’s certainly the way I like to live my life, and it’s why I don’t do concerts in big arenas—I prefer to be in touch with my audience.

MCKENNA: When you were at the height of your success, did you enjoy it?

ISLAM: Yeah. Nobody could not enjoy being the center of attention and having such adoration. But I felt that it was a responsibility, too, and I often changed my track so people couldn’t predict where I was going next. I didn’t quite know myself, but I was trying to be sincere whichever direction I went.

MCKENNA: What’s the most dangerous thing about fame?

ISLAM: Vanity.

MCKENNA: Can you recall the first time you experienced a sense of divine presence?

ISLAM: It was when I was a kid, praying at school—prayer was always with me. I attended a Catholic school, but I was officially Greek Orthodox, so I couldn’t take part in many Catholic rituals. That led me to be a kind of observer within the Christian faith, and allowed me to maintain my belief in God without being tied to any particular denomination.

MCKENNA: During the mid-’70s, you devoted most of your time to searching for some kind of spiritual anchor. What prompted that?

ISLAM: Being larger than life, or being projected as such in the music business, leads you to question yourself. Some people try to forget about it by taking drugs or too much drink, but I was never like that. I was aware that there were very serious, big questions, and I was petrified about what might be in store for me.

MCKENNA: What did you find in the Islamic faith that was lacking for you in other spiritual paths?

ISLAM: It was the most direct and encompassing message I’d ever encountered. I was confused by many of the spiritual books because they used metaphysical and theological terminology I didn’t understand. But the Koran was very clear, especially about the fact that every soul eventually must meet its Maker and then be questioned. That, to me, was a wake-up call.

MCKENNA: What’s the most widely held misconception about Islam?

ISLAM: That there’s no link between Islam and Christianity and Judaism. There wouldn’t be Islam if there wasn’t Christianity or Judaism, because it’s all one long line of revelation. Seeing it from that point of view it makes you ask yourself why Muslims sometimes separate themselves from that large family that leads to Abraham and, even before that, to Adam. The only answer is that we’re conditioned to do it by thinking, Hey, I do things better than he does.

MCKENNA: Did you miss music during those 28 years you were away from it?

ISLAM: No, because I made my life my art. I’d been singing and composing songs for years, and you can lose touch with life if you don’t start living it. That was very important for me because I’m a realist as well as a surrealist. I love to touch life, and that’s what had to happen. I got married and had kids, and there’s nothing more astounding than having your kids look you in the eye, wanting to know what it’s all about.MCKENNA: Much of your music of the early ’70s explored romantic love as understood in conventional Western terms. In 1979, you entered into an arranged marriage, which suggests that your views might have changed. Did they?

ISLAM: Love has many levels, and love of God is very profound. It’s certainly more lasting.

MCKENNA: Why are spirituality and sexuality so often at odds with each other? It seems that most spiritual belief systems have a difficult time integrating those two energies.

ISLAM: The sexual act—separating that from love itself—is centered solely in the body, whereas spirituality is connected to the whole self. Whether it’s a female, a taste, or a sound, all these beautiful things affect our self. We are the perceivers of beauty, and that’s why sex doesn’t quite go far enough. You can go much further with the spiritual.

MCKENNA: Have you done the hajj [an arduous pilgrimage to Mecca, which all Muslims are obliged to perform at some point in their lives]?

ISLAM: Yes. It wasn’t difficult because once you’ve decided to do something, you’re able to overcome any obstacles that appear. You can deal with it because you know what you’re doing it for.

MCKENNA: What’s your definition of sin?

ISLAM: God has decided the rules of life, whereby you don’t trespass on anybody else’s rights, and sin is something that upsets the balance of things. There are three types of sin: sin against yourself; sin against other people; and sin against God. People often sin against themselves and others and misbehave with God, too.

MCKENNA: What’s the difference between knowledge and wisdom?

ISLAM: Knowledge is a thing you can carry around with you, but you may not apply it. Some knowledge is indiscriminate, and it can be damaging. I recently found a wonderful definition of wisdom: It is that thing which results in the maximum good and the least harm.

MCKENNA: What’s the greatest privilege of youth?

ISLAM: Naïveté. That’s a great thing because it makes a fresh outlook possible. We need kids to remind us of how incredible this world is. People are increasingly losing their childhoods too soon, and that’s a danger. There’s a prophesy somewhere that at a certain point in history, children will be gray. It’s weird to think about, but it’s possible.

MCKENNA: When did you become an adult?

ISLAM: I don’t think any of us really do that, if we own up to it. I’m still about 17.

MCKENNA: What aspect of the future, as you envision it, is the most disturbing to you?

ISLAM: There’s a common threat facing all of us—Christians, Jews, and Muslims—and that is the Antichrist. It’s a very deep subject, and it’s a horrendous thing to contemplate. Someone will appear who is, in fact, the opposite of what he appears to be. Some people will believe in him, and that’s really frightening. In Islam, there’s a belief that Jesus will return to destroy the Antichrist, which is something many people don’t know about the Islamic faith.

MCKENNA: When you returned to music in 2006, did you have any doubts that it was the right thing to do?

ISLAM: No, because it was leading me toward a bridge, and bridges are good. We need them to cross over some of these torrential waters.

MCKENNA: You’re currently working on a musical, titled Moonshadow, that’s slated to open in London later this year. What’s the story there?

ISLAM: I’ve been working on it for six years, and it’s not finished yet, but it will actually see the light of day this year. It’s a story about a world of darkness where only the moon shines, so

people have to survive in a sunless world. The central character is a young boy who has a vision of another world where the sun shines every day and people are at peace. He shares his dream with his school friend and promises that he’ll take her to this world one day. Things go wrong for him as he grows, then he meets his moonshadow, who gives him the courage to seek that world of the lost sun. It’s an epic, everyman story, and it’s autobiographical, too. I met Paulo Coelho yesterday, and I told him how much the play was inspired by The Alchemist.MCKENNA: Where did you run into Paulo Coelho?

ISLAM: At this thing called the Fortune Forum in London where Ted Turner was giving a talk. Turner has given away a billion dollars, and I like people like that. Fortune Forum is a philanthropic organization that concentrates on one charity or objective every year. Joss Stone was singing.

MCKENNA: What are you currently listening to?

ISLAM: I’ve been listening to George Harrison. Klaus Voorman recently made a record for his 70th birthday and asked various musicians to select a song he’d played on and do a duet with him. Klaus played on most of George’s records, so I chose “All Things Must Pass” and “The Day the World Gets Round.” I love listening to George’s music again—his spirit is fantastic.

MCKENNA: Your son is a musician. How did you feel about him going into the music business?

ISLAM: I had some trepidation about that, but he has his own views about what he wants to do, and I have to accommodate that. My son advises me a lot these days. He introduced me to the Red Hot Chili Peppers because he wanted me to hear the production on their records. It was quite impressive, I must say. He also likes Eddie Vedder, who I met recently. I happened to be having breakfast at Shutters [the Los Angeles hotel] one day, and Sean Penn was across the room. We kind of clocked each other, then made arrangements to meet the next day, and Sean brought Eddie along to breakfast. He’s got a great aura about him.

MCKENNA: Are there musicians who you would like to work with?

ISLAM: I’d like to work with Bob Dylan someday. His son Jesse did a lovely film for a new song that didn’t find a home on this album. It’s kind of a joke song about the incident in 2004 when I was on my way to the States to make a record and was denied entry into the country. [Ed. note: Available only as a single, Yusuf’s song about the incident, “Boots & Sand,” features Paul McCartney and Dolly Parton.]

MCKENNA: How do you feel about America?

ISLAM: America was my home for a very long time, and it’s a fascinating, pioneering country that many people look to. In the recent past it hasn’t been doing very well, but there’s a great new hope now with the election of Obama. America took a very big leap there and proved that it still has the edge as far as being able to do things many other countries may find difficult.

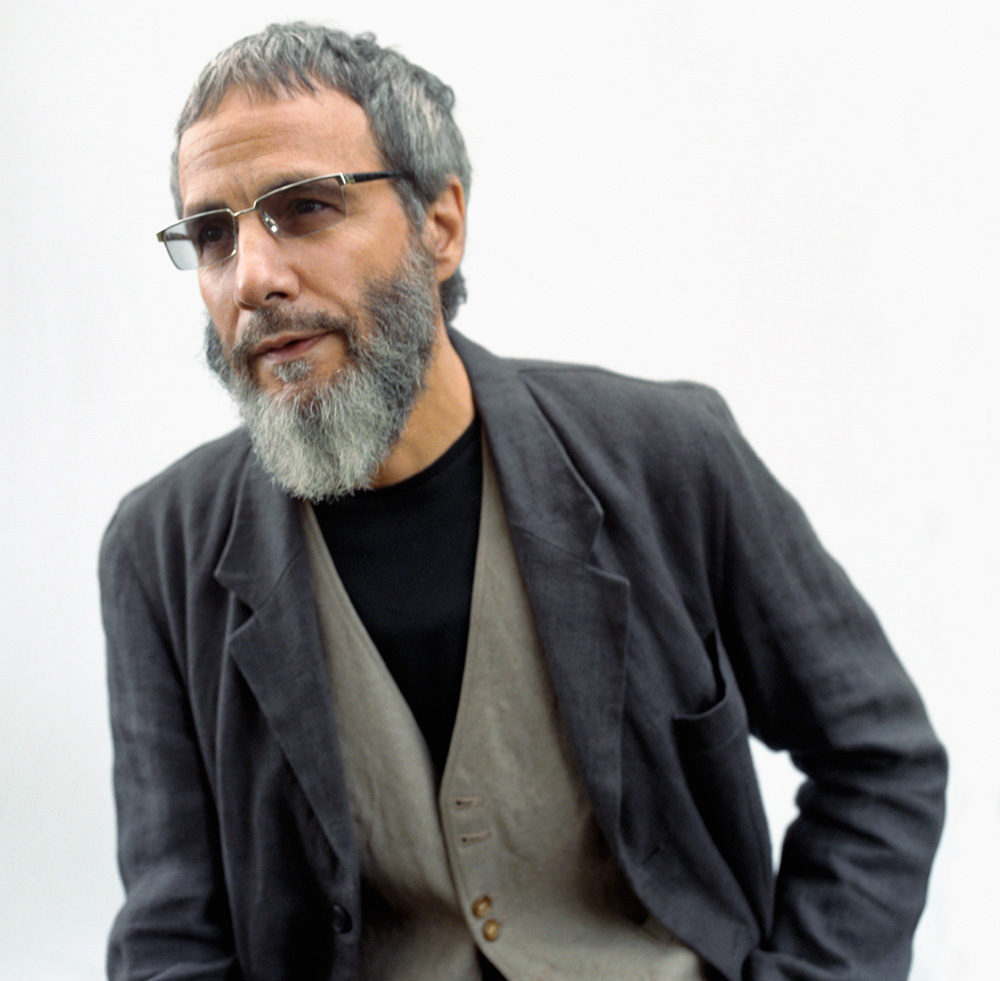

Photo: Yusuf Islam, May 2007. Photo: © Greer Studios/Corbis Outline.

Kristine McKenna is a Los Angeles–based curator and writer.