Wooden Wand Settles Back In

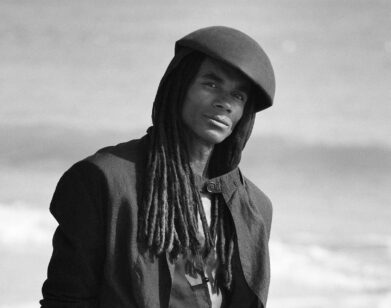

JAMES JACKSON TOTH. PHOTO COURTESY OF LEAH TOTH.

Whether or not he’s a household name, James Jackson Toth is unquestionably one of the essential names in experimental-Americana-psychedelic-folk-country of the past decade. Yes, the crazily prolific Toth really does deserve a five-layered hyphenate, and then some. For most of his career, he’s recorded as Wooden Wand, and he’s never been one to linger too long in one place—neither GPS-wise (he’s lived in Staten Island, Purchase, NY, Brooklyn, and now Tennessee) nor musically. In the early aughts, he was notable for his work with the psych-folk outfit The Vanishing Voice, as part of the then-inescapable “freak folk” scene; but he moved just as quickly to a more straightforward, lyric-driven form of Americana. In 2007, he even jettisoned the Wooden Wand alias, the better to move on sonically.

And yet “moving on,” the following year, came in the form of Waiting in Vain, a record released under Toth’s own name. Despite its musical merits, Waiting in Vain was in James’s words a “catastrophe”—both in terms of the way it was handled by the Rykodisc label, and for its ensuing tour, which resulted in Toth splitting with both his band and his wife.

But that was then, and having put that annus horribilis behind him, things are looking up. The Wooden Wand moniker is back, and with it a fine, nuanced and darkly wry new album called Death Seat, released on Young God Records—the label run by Swans’ Michael Gira, who produced the record and has become an outspoken, if prickly champion of Toth. And, maybe best of all? James is about to remarry. So it was an upbeat Wooden Wand that I spoke to this week from Murfreesboro, TN, days before the release of Death Seat.

JOHN NORRIS: James, this new album is your first release in more than two years, which is quite a wait for you. In the past you were so prolific that there were times when you would have several records out per year. Do you think there’s more anticipation with a longer wait?

JAMES JACKSON TOTH: It could be. I could definitely be accused of spreading myself too thin before. And a lot of that is Michael Gira’s role, which extended beyond just a producer role, he’s kind of taken on a mentor [role], as far as that stuff is concerned. The shelf life of stuff is so short right now, the way people experience music is so different as compared to when I was growing up. Release dates are sort of this ethereal thing, I mean, what’s a release date anymore? But you know, I still get excited for Tuesdays.

NORRIS: Exactly, it’s a hard habit to break. You mentioned Michael, he has said that you guys had dozens more songs could have made the record. So I guess in terms of writing and recording, you’re still pretty prolific.

TOTH: Yeah, I’m prolific to a fault. Actually, I think the final tally was we had 157 songs, which is obscene.

NORRIS: Oh, my God.

TOTH: Yeah, it’s crazy, I’ve never experienced such a thing as writer’s block. But then again, I don’t want to be the Ryan Adams of psychedelic folk, either. I’ve got to rein it in a little bit and kind of separate the wheat from the chaff. But I’m a notoriously poor judge of my own work. I never know what’s good. My favorite songs are the ones people kind of turn their nose up at.

NORRIS: Had all 157 songs been written fairly recently?

TOTH: No, we plumbed the archives a little bit. You know, there were even more than that-there were songs I wouldn’t even play for Michael. I wouldn’t dare, ’cause he’s kind of a harsh critic, in the sense of being a true old-school producer. He pores over the minutiae of these songs, and he’ll challenge me on things like “Well, what does this lyric mean, James? What are you trying to say here?”

NORRIS: Well, he definitely has championed you, with this much-read press release letter, calling you a “great American songwriter” and likening your spirit to that of Waylon, Willie and Hank. That’s some high praise.

TOTH: Between you and me, I was a little embarrassed—I am really happy that he feels that way and he is enthusiastic, but it’s shamelessly hyperbolic and I have to give that promo CD to friends to play it and I almost want to take the back cover off! His support and those words mean the world to me. If I could go back in time and read those words to sixteen-year-old James, I would be psyched.

NORRIS: So I know that the song “Death Seat” goes back a few years. But what about titling the album Death Seat?

TOTH: Well I actually come from two generations of New York City cops, and I actually didn’t know that people knew what that meant. But he would always refer to the passenger seat as the “death seat,” and the chorus is a not-very-funny joke about the “God is my co-pilot” thing. But I wrote it in ’97, so be kind. That was the idea. Michael actually wanted to call it Death Seat. I wanted to call it Servant to Blues, but he didn’t like that.

NORRIS: So that title doesn’t necessarily indicate a theme throughout the record, of mortality or loss?

TOTH: Well I’m obsessed with those things, they’re perennial themes for a reason… I was raised Catholic, and the duality of light and dark, good and evil, in everything from gospel music to Nick Cave. It’s just interesting to me when people work in those parameters. But I also think of it very loosely as a blues record. It’s the one thing that ties it all together, it feels like the Wooden Wand blues album.

NORRIS: Speaking of faith, the album has references to Cain, to Jesus Christ, to heaven, to “flying to God.” Is that just something that comes naturally to you?

TOTH: Yeah, I’m probably less spiritual than one might glean from the lyrics. It’s one of the indelible marks of being raised Catholic leaves. I milk it for all it’s worth, but that imagery is really strong. It’s part of the culture. My family didn’t even necessarily go to church, but my mother’s Italian and there was the specter of God all the time. But when I did go, there’s a lot of kind of morbid imagery that really sticks with you as a kid, and I come from kind of a metal family too. My cousin was in Type O Negative, so there was kind of metal in my family too. Those two things combined, and I was listening to Slayer as I was, like, receiving confirmation. You can’t escape that, it’s something that leaves a mark on you.

NORRIS: We’re here on the verge of CMJ here, and all the madness that involves. You grew up in Staten Island, you did your Brooklyn time, and I know you are in touch with people here—including the guys in Woods, who you used to play with. Do you miss New York, or are you quite happy being away from all of it?

TOTH: I’m pretty happy. I get back there, my family still lives there. And I miss the food, I mean I’ve given up trying to buy pizza or Chinese food here. But still, even when I was twelve, I was dreaming about tumbleweeds and I just couldn’t wait to live somewhere rural-and I’m still not there yet, but I’m getting closer. I don’t know, some people are wired for the city and some people aren’t. I just don’t know how artists can create in a place like Brooklyn. You walk outside and it’s just like competition it’s like you’re on a catwalk. The sounds, the sights, it’s like you’re oppressed by ambiance you know? Whereas here there’s wide open spaces and quiet and all your neighbors are firefighters or they own gas stations and you just feel more like a real person. You feel like an individual, ’cause you’re the songwriter! Rather than like, everyone saying, “What band are you in?”

DEATH SEAT WILL BE AVAILABLE OCTOBER 26 ON YOUNG GOD RECORDS.