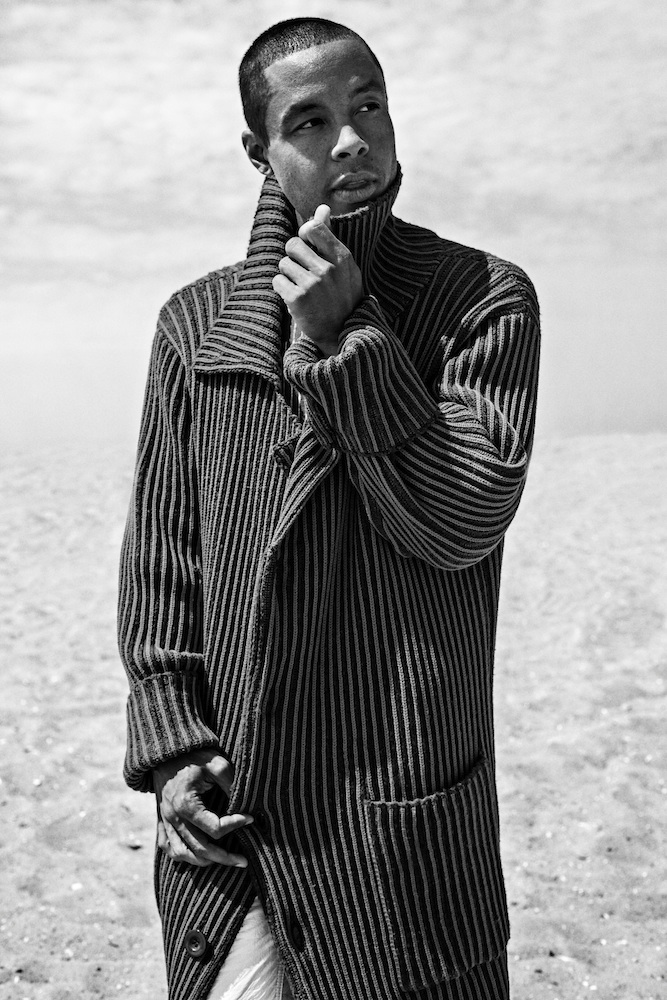

Wills’ Way

WILL JOHNSON IN QUEENS, NEW YORK, JUNE 2016.PHOTOS: VICTORIA STEVENS. STYLING: SHEYNA IMM. GROOMING: NATE ROSENKRANZ/HONEY ARTISTS USING ALTERNA HAIR CARE.

Will Johnson’s latest project, WILLS, began with a demo recorded for The Weeknd. With producer Chris Zane, the native New Yorker reworked “First Time,” a song he had previously released on a mixtape called Bad Études under the moniker Gordon Voidwell. Then The Weeknd started working with songwriter and producer Max Martin and became an international star. “He was really into ‘First Time,'” says Johnson, “But I think that maybe it sounded a bit too much like old Weeknd or something.” Johnson and Zane were left with their demo: “It was the first time I’d heard my voice properly recorded in a studio and heard drums mixed by someone that wasn’t myself, and it made a huge difference,” Johnson explains. “I was like, ‘I still love this; I still love that we did a studio version.”

Next month, Johnson will release his first self-titled EP as WILLS. Consisting of four songs, the EP is mature and polished, and fits in with the R&B and electro-pop musical landscape of the moment. It is an accumulation of a complicated musical history: the son of musicians, Johnson has been making music throughout his life with and without others. Between 2010 and 2014, he operated as the aforementioned Gordon Voidwell and amassed quite a following. A DIY blend of funk, pop, R&B, and general whimsy, Bad Études, for example, was praised by music blogs like Noisey, Complex, and Pigeons and Planes. But, from the very beginning, the mission statement of Johnson’s alter-ego was misinterpreted. Created at the suggestion of Guillermo E. Brown, one of Johnson’s professors at NYU’s Clive Davis Institute of Recorded music, Voidwell was a deconstruction of the myopic hipster music scene. As Johnson tell us over the phone, he was “making a commentary about race, masculinity, gender performance, and who’s allowed to perform what in that space.”

Among the first songs Johnson released as Voidwell was the tongue-in-cheek “Ivy League Circus,” in which he lists the assets of a love interest: “I envied you for your smiles/Your family tree, it’s rank and file/The summer house and first class miles/Your silver knife and sharp denial.”

“‘Ivy League Circus,’ was a straight-up commentary about being educated, having that consciousness, having many, many, many realities about your identity, and then being smacked in the middle of this surreal Brooklyn world that seems absurd,” he says. “It was about the absurdism that exists in those worlds, and trying to have a conversation and use humor about it, but also realizing that there’s something really dark about that.”

Much to Johnson’s discomfort, the song worked too well, and he found himself embraced by and profiting from the very scene he was critiquing. He retreated from New York to St. Paul, Minnesota, gave up his cell phone, and started working alone in a local, internet-free studio. Though still working under the Voidwell name, by the time he released Bad Études he was already moving on in aesthetic and attitude.

EMMA BROWN: When did you start making music—in college?

WILL JOHNSON: I was, as a child, in a touring choir. That’s a huge part of my musical training. It was a youth choir that did classical music, jazz music, and gospel music called the Boys Choir of Harlem. It was a three-year commitment of my life; pretty much I was on tour for three years as a child. It was a lot of kids from the inner city, whatever that means in New York, that would come to this school and we’d get world-class vocal training and learn music theory and different styles of singing and styles of composing. We all took instrument classes as well and learned music theory. I think the point of that was not so much for people to become professional musicians, but just to give kids a tool to focus. A lot of the kids ended up doing really well, even though very few are actually still in music. [We toured] mostly throughout the U.S.—in those three years we went to probably every state at least once. We would hit the major cities and play performing arts centers and venues that would have a built-in subscription audience. We also played places like Carnegie Hall and Avery Fisher [Hall, at Lincoln Center].

BROWN: Was it social? Were you friends with the other boys in the choir?

JOHNSON: Yeah, definitely. It’s such a unique thing; the kids who I grew up with in that choir, we all had such a specific experience. It’s so focused on this duality of growing up in the hood and then also having access to learning about Bach and Brahms and Mozart. And also then bringing that back to whatever neighborhood you’re from and being like, “Oh my god, no one in this neighborhood knows that I’m experiencing on a day-to-day basis.” [laughs] So the bonds were pretty tight at that age. I think a lot of the kids that were friends during that period are still pretty close to each other.

BROWN: Did you leave by choice or is your time up after three years?

JOHNSON: My sister was going to this really amazing private school on the Upper West Side, and every time I’d visit that school, I would long for an education and space like that. That’s one of the downfalls of living in New York City, you really get to see the disparity of resources; as a kid you get to see, “Wow, some kids are living with so much and some kids are living with so little.” Or I got to see that. I don’t know if everyone gets to see that, but visiting those private schools you see how and what education can look like. It made me really want that for myself. So my mom got me a tutor to catch me up to speed and we started applying for New York city private schools, which was a crazy process. Then I went to a pretty crazy private school called Fieldston, which is up in Riverdale in the Bronx.

BROWN: And you grew up in the Bronx?

JOHNSON: I lived in the Bronx up until college, and I went to school in Ohio for one year then I transferred and went to NYU. By the time I transferred to NYU, I moved to Brooklyn with the rest of everyone. I lived in Brooklyn and Hell’s Kitchen for a while after college and then I moved to Minnesota.

BROWN: Did you go to Oberlin or one of those colleges?

JOHNSON: Yeah, exactly. I went to Oberlin for a year. I was playing with my high school band at the time, and we were, especially second semester, on the East Coast a lot. I missed a lot of school and I ended up getting a no-entry at Oberlin, which is equivalent to “I can’t grade this student because they weren’t in this class.” [laughs] So after that I transferred.

BROWN: What was your high school band like?

JOHNSON: Oh man. We thought that we were The Roots and Radiohead combined, but we were just overeducated kids making rap music that we thought was awesome. No one was checking us, like, “You guys are speaking a really specific language that no one else understands.” [laughs] But it was cool; it gave me a sense of how to work collaboratively with other artists and musicians. I learned a lot about self-producing and sound design, and how to use samplers and synthesizers.

BROWN: Did you just play house parties or did you have proper gigs?

JOHNSON: We would play New York City venues. We could actually get huge crowds to come from our schools—they just would support us because they were friends. Then it was this magical thing that happens with 18-year-old bands, where if you have friends who go to colleges, they all start disseminating your music around the college and you get this amazing following. It’s kind of embarrassing to say, but we ended up playing like the Ivy League rounds. We would play all those spring concerts—one year we played with Wilco and the Nappy Roots, which was so wacky. [laughs]

BROWN: What was your band name?

JOHNSON: I can’t say it. [laughs] I can’t put that out there. You’ll probably be able to find it.

BROWN: I know your parents were musicians. What did your parents think of your band?

JOHNSON: My parents have always been supportive because they’re artists. They’re free thinkers and they’ve instilled this value of just create, don’t worry about the genre, don’t worry about the specifics of technique even. As long as you’re creating, you’re being true to yourself. My mom doesn’t even play music anymore really, but she just has such an artists’ heart and an artists’ soul; everything she touches is done in the guise of knowing yourself and learning yourself.

BROWN: So they’re not purists?

JOHNSON: No. But my dad was a pretty notorious, strict jazz guy. He had a student who was in that band Living Colour, this guy Vernon Reid. I met Vernon unrelated to my dad through music world, and he was telling me that at the time that he met my dad, my dad was like, “Everything that’s not jazz is bullshit.” By the time that I knew my dad and got to have a creative relationship with him, he was not on that. [laughs] I think he had changed based on his own life and had his own relationship to the jazz world—what worked about it for him and what didn’t work. By the time he was being a father, that didn’t apply, but he did have his own sort of struggle with being a purist in some form.

BROWN: When you were in college, were you actively thinking, “When I graduate, I’m going to become a musician?”

JOHNSON: No, not really. Honestly, especially with how the world is now, there’s part of me that still feels a responsibility to go to law school—just watching the news, seeing what’s happening in Minnesota, in New York, in Dallas, in Louisiana. Being a musician is awesome and I’m always going to be a musician no matter what I’m doing—there’s nothing that will ever stop me from making music because it’s just a practice. But I’ve been brushing up on logical reasoning and things that apply to taking the LSAT just because I feel like there are other ways of thinking that could be strategic in terms of actually impacting social change. I don’t think of myself necessarily as being a musician so much as that practice has enabled me to speak to other people and voice greater concerns to other people.

BROWN: The first song I could find of you as Gordon Voidwell was “Ivy League Circus.”

JOHNSON: Man, that was so long ago. It’s funny because that project transformed into then playing with a lot of the people from those bands. At that point, I had to be aware and be mindful of the fact that the people from those bands are actually people, and it’s my responsibility to still be compassionate towards them because a lot of those people ended up being great people. [I also had to be aware that], “The shadow of this is I’m actually profiting from this thing that I was once critiquing.” All of us—no matter if you’re black, white, man, woman, non-gender identifying, whatever—all of us have complicated realities and I think that the world, for whatever reason, has up to this point kind of been like, “Everyone express your most simple reality,” as opposed to, “Express everything you can possibly express and try to find a way to make that all be synthesized.”

BROWN: Do you feel like you’ve synthesized your many realities?

JOHNSON: That’s the quest of life. I don’t want to say that I have because for me, if there’s one reason to live it’s to recognize the fact that one, I myself have so many realities and am experiencing so many different things all at once, but also that there’s a way to be in touch with everything at once.

BROWN: Did you ever feel comfortable profiting from the Gordon Voidwell persona?

JOHNSON: That’s always been so tricky for me because that project is so DIY, and it’s so punk. The whole point of it has been, “I don’t really care what people are telling me I’m supposed to do, I’m going to do what I feel is right for me.” When that becomes profitable, it’s tricky, because you’re capitalizing on something that’s supposed to be anti-capitalist and anti-free market. There have been various points during the Gordon Voidwell project where there was an opportunity to capitalize on a larger scale, and it didn’t make sense to do that. If I was just being in the present moment, I always had everything I needed. It didn’t demand having millions and millions of dollars, I found ways to get grants, to work with art foundations to have funding. I just was really focused on keeping control of that project, whereas the new stuff that I’m doing, I’m open to the fact that other people have good ideas, and valuable ideas. I think part of that is just learning myself and that I don’t have to feel attacked or threatened by the fact that other people are operating with varying degrees of brilliance and intelligence.

WILLS COMES OUT SEPTEMBER 9, 2016, VIA IAMSOUND. FOR MORE INFORMATION, VISIT WILLS’ FACEBOOK OR TWITTER PAGES.