Wild Belle’s Dream

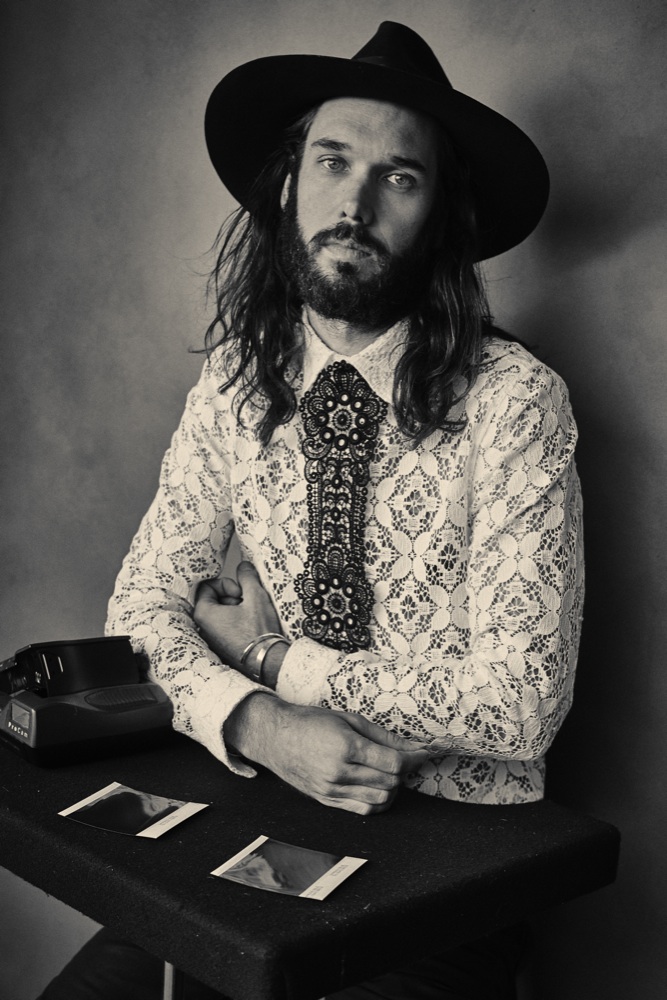

WILD BELLE (ELLIOT AND NATALIE BERGMAN) IN NEW YORK, APRIL 2016. PHOTOS: CHRISTIAN ANWANDER/HONEY ARTISTS. STYLIST: BRITT MCCAMEY/HONEY ARTISTS. HAIR: WILLIAM SCHAEDLER FOR LIVING PROOF. MAKEUP: DEANNA MELLUSO USING MAC COSMETICS AT THE WALL GROUP. PHOTO ASSISTANTS: MATTHEW HAWKES AND LENNY KOHLMAYER. STYLIST ASSISTANT: RENEE HUFFMAN. SPECIAL THANKS: ATTIC STUDIOS, LONG ISLAND CITY, N.Y.

Brother/sister duo Wild Belle released its much anticipated sophomore effort Dreamland on Friday, the first since the band’s 2013 album Isles. While Natalie and Elliot Bergman’s debut explored Jamaican sounds and world music textures, the follow-up finds a harder rock edge. On a track like “Throw Down Your Guns,” listeners hear Elliot’s experimentation with the kalimba and saxophone as well as more traditional underlying bass and drums, with Natalie’s beautifully raspy vocals proclaiming “Nobody move, nobody get hurt / Throw down your guns, throwdown your guns / In the name of love, I put my hands up.” When it comes to writing, Elliot often leads the production of tracks with Natalie spearheading the lyrics, however, as Natalie notes, “There is no formula.”

During the last three years, Natalie found herself in a heated emotional state following the end of a long-term relationship, so she packed up and left Chicago (the siblings’ hometown) for Los Angeles, hoping to start fresh and leave her baggage behind. The resulting album reflects her overcoming pain and sorrow, yet it also connotes omnipresent dilemmas found within today’s social and political worlds. Through Dreamland, the pair addresses not only what it means to be a community and how to remain truthful in a world saturated with lies, but also how love can act as a powerful antidote.

Tonight, Wild Belle will perform in Los Angeles at The Standard, Hollywood and next week they will play at Brooklyn’s Music Hall of Williamsburg. Just before the release of Dreamland, Elliot and Natalie spoke with their friends and mentors, Tina Weymouth and Chris Frantz, the husband/wife duo now known as Tom Tom Club and also as former members of Talking Heads.

CHRIS FRANTZ: We’re all here, so let’s jump right in. We loved the first record, as you know, but I think this one is even deeper, wider, and groovier. Did you use the same musicians?

ELLIOT BERGMAN: We made the first record in a very insular place, in a studio in Michigan. This one opened up the brotherhood and we had a lot more musicians involved, but still the same core of people. We started experimenting with more electronic production and worked with a few really great producers. I spent a lot of time with Doc McKinney and I learned a lot from him. He works a lot in Ableton and I was working with this thing called Maschine, so those factored into the developing of a more hybrid sound.

TINA WEYMOUTH: It’s been three years since the last release. Is that a factor from touring so much?

ELLIOT BERGMAN: We toured so much after the first record, but we spent the last few years recording every day so we have a new catalog of songs, sounds, and ideas. You go back and start honing it and say, “What flows together, what’s a compelling story, and what are we trying to talk about with this record?” The music business has changed, and our country is going through a lot of changes right now. So on Dreamland, as artists, we have to be the ones waving the freak flag and saying, “What is the dream here, what is a brotherhood, and what is a family? What are we trying to do here collectively, what should we be thinking about, and what should we be talking about?” On this record there are a lot of themes of losing love, but you realize that love has to be at the center of everything you’re doing, whether it’s artistically, personally, or politically.

TINA WEYMOUTH: Yeah, there is a very mature approach in Dreamland, where Natalie sings, “there’s no use crying.” I thought, “Wow, if only our Middle Eastern brethren knew that,” that the wailing and the smashing of teeth is not the way to go, but rather dreaming, and out of dreams comes a much better reality.

I like that you deal with these universal themes of love, and I thought about the two of you, brother and sister. You’re a very close-knit family. All of us in this conversation have lost a parent, so there is a sadness woven into all of this love. But you’re very strong, you don’t give up, even though one song is called “Giving Up On You.”

NATALIE BERGMAN: I was visiting someone I really admired and the other morning I had a feeling that he was going to break my heart. I told him, “You’ll never see me cry.” There is this shield that I put up because I want to guard my heart and I don’t want people to see me broken down. I think that has to do with the mentality of the record. There’s an apocalyptic vibe on the record; there’s end of the world lyrics, there’s fighting lyrics. So I have shields, but the shields aren’t because I’m afraid but because I want to move forward as a strong warrior. I don’t want to be broken down by the label, by a man, or by anybody trying to fuck up my life. I want this to be a positive and powerful, forward-moving record.

TINA WEYMOUTH: That leads to the next question: When you are writing do you talk about lyrics together? I once asked Annie Lennox, who did the writing for The Tourists, how it worked out. She said it was never 50/50, that it was always 25/75, and it would flip around from one to the other.

NATALIE BERGMAN: Absolutely. [laughs]

ELLIOT BERGMAN: I think Natalie gives more of the lyrical stuff and I come in as an editor. Sometimes I’ll have an idea for a chorus or for the last verse, but she does most of the heavy lifting. Everything on this record came from a different place; it’s finding unusual things that set something off in you and get you inspired and moving. Once you have a few pillars set up, you can start filling in the space and creating a sonic world where you’re happy to live for a while.

NATALIE BERGMAN: When we start building a song from scratch, I often don’t begin the lyrical process until we find sounds that are exciting, sexy, and dazzling. Sometimes the dazzling sounds that we fall in love with are coming from goat hooves or a busted steel pan drum or an out of tune harp. It can be janky, it can be beautiful, but whatever it is, that’s what gets me going, what starts the lyrical process. I need to have a universe of sound before I can figure out what the song is about.

TINA WEYMOUTH: Your sounds are full of imagery and emotion as well. You don’t deal with a lot of irony. You’re very sincere. You’re dealing with things in a very strong, powerful way, but at the same time it’s kind, you’re not introducing more suffering. When we were growing up, the days of Velvet Underground, there was a turn against the hippies and a bitterness, a rage, an anger that led directly into depression and nihilism. You guys seemed to have floated past that. You’re above the clouds where the sun is shining. But I know you guys suffered just as much as anybody…

ELLIOT BERGMAN: We have to keep all that stuff on the inside. We’re from Scandinavian descent, so we have to keep a tight upper lip.

NATALIE BERGMAN: I feel like you just went into my heart and gave it a name, which is beautiful because most people aren’t able to describe that emotional process. There’s a deep darkness that resides in all of us. People have this misperception of me as this laid back, easygoing gal, but I get anxious and scary and sometimes neurotic. I just think the depth of our music comes from a spot in my heart that is honest and loving, no matter what turmoil is going on in my head.

CHRIS FRANTZ: I don’t have a question, but I have a statement. You’re the only band I know who uses the kalimba in a way that is unpredictable and I love that.

ELLIOT BERGMAN: There are many variations of this traditional African mbira or kalimba, but I make a lot of electrified, slightly mutant variations on them. Sometimes they sound like a fuzzed guitar or church bells, a gamelan, or a lap steel guitar. “Rock ‘n’ Roll Angel,” the last song on the record, is this dusty country ballad through our weird Wild Belle filter. Natalie is playing the central riff on this big bass kalimba and I’m actually playing an electric kalimba. Taking something and reimagining it in a new context, dressing it up in a different way, is the sort of thing that is fun for us—just trying to imagine new possibilities for how you thought about sound or what you thought an instrument could do.

CHRIS FRANTZ: I know what I want to say: There was a thing on YouTube that you did, Natalie, called “I’m a Ghost Inside,” which I loved.

NATALIE BERGMAN: How did you find that? I feel like you’re one of 20 viewers. [laughs and sings] I’m a ghost inside, I’m a ghost inside, I’m a ghost inside. Baby, why’d you let me die?

CHRIS FRANTZ: That’s the one. Have you recorded a version of that? If not, I hope you will.

NATALIE BERGMAN: I wanted to be like Johnny Cash, so I made that video in my old apartment in Chicago. I just faced the camera towards me and recorded. But thank you, maybe that will be in the next record.

TINA WEYMOUTH: I think this is a record that will stand the test of time. You guys manage to straddle that really difficult place between electronic music, modern music, and old analog delivery. Elliot, I will always love your saxophone. Do you ever do stuff, like put so much effect on your sax, that I don’t even know it’s a sax?

ELLIOT BERGMAN: Only in private. [laughs] Working with Bill Skivvy on the first record, we developed this signature sound for the saxophone in Wild Belle. It’s this elephant-esque exploding sound. It’s exciting to play the saxophone when it’s amped up so much. That’s how we tried to treat it in Wild Belle. You don’t need to encourage me too much because I’m pretty sure the next Wild Belle record is going to be all saxophone, kalimba, and a little bit of Natalie singing.

TINA WEYMOUTH: I think about Chet Baker. Do you ever listen to him?

ELLIOT BERGMAN: He’s very cool. Seymour Stein came to Detroit and saw my old band. After the concert, he came up to me and said, “I want you to get a shorter haircut, shave the beard, and act in a movie about Chet Baker, where you play the trumpet.” [laughs] I thought that was a funny piece of advice: Get a haircut, shave your beard, and act in a movie. I think there is a Chet Baker movie coming out soon, but I missed the boat.

CHRIS FRANTZ: Tina missed the boat on the Nina Simone movie. [laughs]

NATALIE BERGMAN: I thought the documentary was really moving and powerful. I thought they did a really beautiful job.

ELLIOT BERGMAN: There’s a line where Nina Simone is basically saying that all artists are trying to be free.

TINA WEYMOUTH: That’s a real blues concept isn’t it? The poetic soul is free while the body is enslaved to this dimension.

ELLIOT BERGMAN: It’s a gospel concept too, but it’s a human concept really. One of the ways that we’re able to be free is through the things that we create. It’s hard to protect that and there are lots of forces that can lock you up.

NATALIE BERGMAN: The song “Coyote” on the record actually has to do with that. I believe that I’ve found my voice, but sometimes I feel a bit like a prisoner with the label. There are moments where I feel like my hands are tied behind my back.

TINA WEYMOUTH: Freedom is something that is very difficult. People have this illusion that it’s really easy and never realize that you’re always walking on a tightrope when you’re in the creative moment of making something. But you guys are really trying so hard to avoid that. You’re very smart and make it look incredibly easy.

ELLIOT BERGMAN: Tina, I don’t know if you remember this, but one time we were at your place and you had prepared this beautiful lunch. We were talking and you said something that really impacted us: “You need to figure out a way to be able to love the way you sound every night.”

TINA WEYMOUTH: Yeah. [laughs] That’s true.

ELLIOT BERGMAN: It sounds simple but it’s such a profound thing. If you can love the way that you sound every night, that’s amazing. We ended up getting this sound system made by our friend at Bag End and we travel with it. It looks easy, but it’s these massive 100-pound speaker cabinets that the band drives around and loads into the small clubs that we play every night.

NATALIE BERGMAN: Elliot and I joke how we think how it’s one of the greatest accomplishments of our lives. [laughs]

ELLIOT BERGMAN: Figuring out what’s coming across to the audience is so hard because you are in a different space every night, trying to connect with an audience and bring people together. When you’re in a new space and there are new people, there are nights when you feel like, “What is happening in my head is translating to this audience and they’re understanding us”—there’s sympathy, there’s empathy, there’s a communal experience happening—and then there are other nights where what’s happening on stage seems completely disconnected to what’s happening in the audience, or the audience is talking.

One night I ended up yelling at the most distractive, loud, disinterested audience. I was embarrassed about it afterwards, but they really responded. I asked everyone to come close to the stage and to stop talking, and then we had this pump of energy. Natalie kicked the monitor off the stage and broke this lady’s foot. [laughs]

NATALIE BERGMAN: The sweetheart was right in the front row and I literally broke her foot. For the rest of the night, I was pretty much trying to find her so she wouldn’t sue me. Sometimes I have such a murderous temper, but I would never want to hurt a fan and I did. I really am sorry about that.

TINA WEYMOUTH: But that goes both ways, Natalie. Sometimes audiences break people. The great [Frederick] Toots Hibbert of Toots and the Maytals doesn’t tour anymore because of a jerk who threw a bottle at him and put him in the hospital. Once a murderous fan snapped a microphone back and broke my front teeth. It works both ways.

ELLIOT BERGMAN: That’s something that should be spoken of more often because I think everyone has become very passive consumers of culture. Sometimes when they go to a concert they forget that they’re not sitting in front of a screen, or they are actually sitting in front of a screen because they’re filming the whole thing on their cell phone. They don’t realize that impacts you on stage. It’s a dialogue. We’re not just programs spewing information forth; we’re trying to create something together with the audience.

Music is unique in the fact that it’s happening in real time. There are incredible depths of meaning the ways we’re communicating. It’s visual, it’s sonic, and when people lose touch with that they can easily check out. Then you’re just a thing on a stage, you’re not a real person, and when people lose sight of those connections it gets to be dangerous.

TINA WEYMOUTH: You’re right. It’s a dangerous world we’re living in, in terms of artificial intelligence and computers and the way people are taking the performance for granted. So long as they have the right drugs and like the beat, they’re going to dance in front of a DJ. What do you think about The New York Times not covering festivals like Lollapalooza and Bonnaroo because they think they’ve lost meaning?

ELLIOT BERGMAN: I can understand the sentiment. It can be harder and harder to connect. How can you feel a connection when you’re in a sea of hundreds of people? Maybe there’s something very powerful in that, but there needs to be a space for more intimate moments of connection and things that are a little more delicate and less manufactured.

It is hard to know what to do because if people don’t want to buy or pay for music, then you’re forced to end up on the Bud Light stage of every festival or have a Pepsi backdrop. You want to keep creating, making music, and making art, but it’s a very compromised landscape right now. There’s something corporate at every turn, and there’s an increasingly lax attitude towards it. It’s sort of like, “Well, that’s the way it is. If you can’t sell a record, you have to sell, not even a t-shirt, but toothpaste or a car or sneakers.” You just think, “Why do they get to own that too? Why do they get to own the way that we look and the way that we think about this?”

NATALIE BERGMAN: Or why does Spotify get three exclusive tracks that they’re not paying for? Why do they get to use us, for their brand, for free?

TINA WEYMOUTH: Right, it’s not a two-way street with them. This is what the trickle down of the new conservative oligarchs has bequeathed us. That’s why this election is going to be the most important of all for our future.

ELLIOT BERGMAN: It’s true. There’s a lot of work to do right now, and it’s all a part of Dreamland and the questions that we hope it asks—what is our dream and what is our dreamland? One time we were talking about Tom Tom Club and you said, “It’s not just me and Chris, it’s supposed to be a club, it’s supposed to be fun and inclusive.” When we started making this record that was something we thought about. There’s so much focus on in Wild Belle—”You are brother and sister, tell us what that’s like, do you guys fight,” very inane almost tabloid-style questions—but look, we’re not celebrities. We are brother and sister, but we are two artists trying to do something together. So what does that really mean—who is your brother and who is you sister? How do you love somebody as if they were your brother? We have some power to love people through art. You can love your audience and you can love the art that you make, but trying to make love be in the center of what you’re doing is important right now. It’s important to do it in your art and in the political landscape, and maybe love is the most radical and political thing you can do.

DREAMLAND IS OUT NOW. FOR MORE ON WILD BELLE, VISIT THE DUO’S WEBSITE.