Closer Than You Think

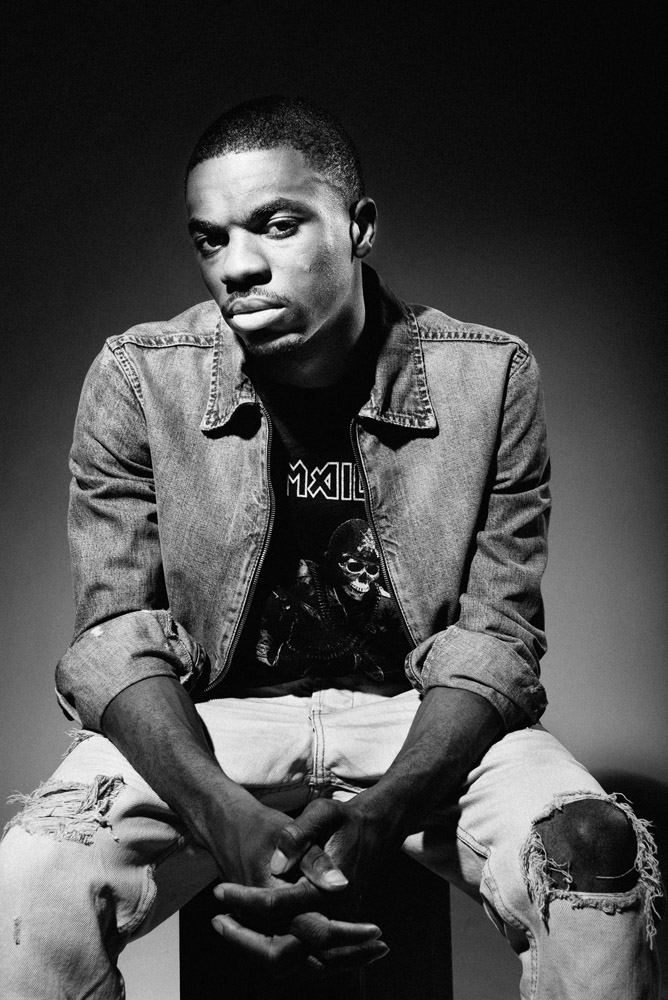

VINCE STAPLES IN LOS ANGELES, JUNE 2015. PHOTOS: CARA ROBBINS. STYLING: LISA MADONNA. GROOMING: MARISSA MACHADO AT ART DEPARTMENT FOR BAXTER OF CA.

Thirty seconds into the music video for “Señorita,” 22-year-old rapper Vince Staples emerges from a southern California stucco house like the Roman poet Virgil, ready to guide listeners through life in a modern day inferno. Based in Long Beach, California, a neighborhood deemed “deadly” by internet polls and crime statistics, Staples delves deep into the matters of life and death with a nonchalance and conversational ease that’s altogether enrapturing and unsettling. Although he’s made many guest appearances on albums from various members of Odd Future and self-released his debut EP Stolen Youth in 2013 with production by Mac Miller, tomorrow marks the release of his debut LP, Summertime ’06, via Def Jam.

In his music, traces of cliché hip-hop bravado are deeply rooted moral justifications; meekly statured depictions of violence become intimate and chilling opposed to callous; and, as his close friend Earl Sweatshirt has said, his ceaseless flow should require gills.

When Staples enters the restaurant where we’re meeting for lunch, he sports tan Nike combat boots and a black hoodie with LBC embroidered on the front. He orders a ginger beer and a kale salad (per the waiter’s recommendation), but also tries the pancakes (he isn’t impressed). His phone buzzes throughout the conversation and meal—it’s either A&R, his girl, or Jhené Aiko—but it never occupies more than a sliver of his attention. Staples’ focus, much like his vision, is razor sharp.

JAKE BLAIR: How do you feel about Summertime ’06 now that it’s finished?

VINCE STAPLES: I’m kind of nervous to see what happens, but in a good way. I’m trying to get the Lana Del Rey effect, like, “What the fuck is this bullshit?” The best thing about music is when you don’t know if it’s good or not. Like, if I sit down and listen to Metallica, I can’t really tell if it’s good. James Brown? How could anyone listen to James Brown and think, “Yeah, this is good”?

BLAIR: But you can like how it makes you feel, right?

STAPLES: Yeah, but it’s about a moment—this is a very specific moment, a very specific experience. I think there’s a shift that hasn’t happened [to me] yet. At some point in time people decided you needed to be the best at some shit—but what’s that even mean? What does it mean to be the best? To “make it,” what are you making?

BLAIR: Both the EP and “Señorita” are noticeably distinct from your older music; they really bang. I feel like an idiot saying something like that, but really.

STAPLES: You have to captivate and entertain if you want your message to get across. If people don’t die in The Godfather, then what is it? It’s boring as fuck.

BLAIR: Do you have a favorite character in The Godfather?

STAPLES: I hate that movie. I fuck with the dudes he shot in the hospital, though, because they took initiative. This is my thing—I hate fake crazy; if you’re gonna be crazy, then just be crazy.

One of my younger homies, he just went to jail, and some people came to me and were like, “Bail him out,” and I said no. Why would I bail him out? He’s going to prison. Let him sit and get some time served. You want to be crazy, but you don’t want to go to jail. You want to shoot people, but you don’t want to kill people. That’s such a misleading thing. That’s why we have this complex in hip-hop. Even the man Mr. Don Corleone himself, he was willing to sin, but he wasn’t willing to do the work himself.

BLAIR: But maybe that’s because he knew who he was?

STAPLES: Yeah, he knew who he was, but he was using mother fuckers. I fuck with Joe Pesci. I fuck with Goodfellas more than Godfather; it’s more realistic. Look, I was a little kid, we was little kids, we fucked with the wrong person, we got stuck, and bam—somebody dies, somebody tells, and somebody goes to jail. That’s life. That’s life for everybody in that situation. It’s always, “We’re young, he’s older, he can use us to do some shit. We make the wrong dude mad, somebody dies, somebody tells, somebody goes to jail.” It’s a cycle. It’s been like that since I was in sixth grade. That’s how it went with my mom and dad’s people and it’s always gonna be like that. So when I watch that movie I think, ” I’ve seen this before.” I’ve never seen kissing hands or any shit like that, at least where I came from. I understand that it’s real in a sense, but not where I come from, not in terms of being relatable.

BLAIR: But relatability is subjective, isn’t it? You don’t have any control over whether something resonates with someone else…

STAPLES: Yes you do. Certain aspects of life—loss, gain, happiness, sadness—everything ties in to that. Jimmy and Henry are making a lot of money; they’re happy. Then Jimmy goes to jail; his wife is sad. Henry’s angry; he stabs a dude in the back. I’ve been that before. Henry falls in love with his wife; that’s happened to me before. You get what I’m saying? Basic emotions can be conveyed through anything. As long as you show people that you’re human, they’ll relate to it.

BLAIR: There are a lot of artists who have been in the game a lot longer than you who don’t have that awareness.

STAPLES: So many people that make music don’t care about the people that listen to it; they want their check. I’ll make no money off music and then go get an endorsement deal before I squander my influence, because when I was growing up, we didn’t have anybody. No one cared about people my age when we were growing up. When I was in third grade, 50 Cent came out, and that was a fucked up path to be on—Get Rich or Die Tryin‘. In his music, he killed this nigga, that nigga, robbed this nigga. So we felt like, “Okay, we can do whatever we want, and then we’ll end up rich or dead. He got rich. He didn’t die.”

And where I come from, there’s no common enemy, there’s no “why.” There’s no, “I hate white people,” in North Long Beach between South and Artesia. Like, Chris lives right there and he’s white as fuck; Richie’s Asian; they’re Mexican. So that is out of the equation. The people on the urban side say, “We’re oppressed. We don’t have shit,” and on the other side it’s like, “Man, they’re committing all these crimes and bringing the community down.” Either way, you’re looking at someone else like, “You’re the ones that are fuckin’ up,” because they aren’t around you, so it’s easy from either side of the spectrum. But when everyone is together, what’s the excuse now? That’s all gone now, in a sense.

BLAIR: The “Señorita video” feels like it could be a sort of thesis statement. Do you feel like it represents what your larger message might be?

STAPLES: I don’t have a message. You already have all these people telling you how to live, who to be, what to wear, what to drive, what drugs to do—I just want people to see what I see. Take that for what it is.

BLAIR: As you get more recognizable, do you think it’s going to be hard to stay in Long Beach?

STAPLES: I’d move to Orange County before I’d live down here [in downtown Los Angeles]. I was in my room thinking for an hour about whether I wanted to move to L.A.—it seems closer to work, but that’s not my work; my work is not recording the songs. The work is the understanding of the people that you’re speaking for. The further you get away from that, the further you are from the work.

BLAIR: Who do you imagine your audience being?

STAPLES: Put it like this: we all come from a place and we all know that album sales are bullshit. How many times is Snoop Dogg gonna play? Once, twice, if that? Who’s going platinum? We neglect that. But there’s over a million people in Long Beach, there’s millions of people in Los Angeles. At the end of the day, if it matters out here, then it doesn’t need to anywhere else—I might be wrong, but if I’m wrong, I am wrong, and I am fine with that.

If it’s about more than you being successful, if you’re a voice for a community, then you’re a voice for something more than yourself. I want to have an impact, because I don’t want anybody to have to go through what I went through. That shit sucks. I will never be able to be a better person, in a certain sense, because of shit I had to do, that I wish I never did but I don’t regret. It has always been “fuck them;” you might love everybody else, but it’s still, “Fuck everyone that lives over there.” We all grew up together, we all loved each other at one point in time, and then all of a sudden that stopped—fast. So that’s what I care about, but no one else really cares.

BLAIR: Don’t you think it’s possible to make people care?

STAPLES: You can make people have pity. Care and pity are two different things. Like, “Man, this is so sad,” but if you really care, go give someone money for a funeral, go buy a plane ticket—Jet Blue, $80. Instead, you’ll spend that money on weed and still say you care. We all pretend we care, but no one really gives a fuck. Who is thinking about those kids from Sandy Hook right now? Who cares about all those people that were killed in the theater in Colorado? Their families. Other people felt sad, felt bad for them. It was a pity situation, and that’s needed, don’t get me wrong, but that doesn’t effect change.

What effects change is a change in scenery. Scenery is determined by perspective, and you can change that perspective. When my manager first came to Long Beach, he was like, “Y’all don’t go to the beach?” and we were like “No, we don’t go to the fuckin’ beach.” We say, “It’s far.” It’s not, but that’s what we say; I lived on 7th street, I can walk there in five minutes, and as long as I lived there I did not go to the beach. I was rockin’ outside in the neighborhood, angry about how my life was, trying to fuck somebody else’s shit up. The fact that that’s the majority is the problem. The beach is right there.

SUMMERTIME ’06 IS OUT TOMORROW, JUNE 30. FOR MORE ON VINCE STAPLES, VISIT HIS FACEBOOK.