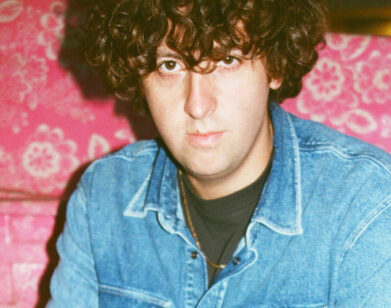

Unknown Mortal Orchestra

Ruban Nielson may be anonymous in his adopted hometown of Portland, Oregon, but the 31-year-old singer and guitarist is already a rock star in his native New Zealand, where he and his older brother, Kody, fronted a grimy, reverb-riddled pop-punk outfit called The Mint Chicks. It was a band that embraced Dionysian stage antics more familiar to the hair-metal set: think smashed guitars, people swinging from light fixtures, and, on one occasion, wielding chain saws on stage. But after tensions between the Nielson brothers began to mount, The Mint Chicks quietly broke up a little more than a year ago. “I kind of had this idea I was just gonna give up music and be a productive member of society,” says Nielson, who moved back to Portland last April to be with his wife and infant son. Music, however, continued to beckon. “I had this idea for a record that I’d always wanted to make but never could,” he explains. “When I was by myself, I got really into psychedelic rock and stuff from the ’60s—stuff with junk-shop tape machines, stuff I always thought was a waste of time or indulgence,” says Nielson. “I hadn’t really told anyone I was making a record—not even my friends or family—but I put one song on Bandcamp and within the next month, four labels called.” Now Nielson is preparing to unveil his new project under the name Unknown Mortal Orchestra with the release of a self-titled debut LP (Fat Possum) in June.

The album, recorded mainly in friends’ basements with bassist Jacob Portrait and drummer Julien Ehrlich, is a heady, ’70s-influenced psych-rock dream—fuzzy and experimental (the opening track “Ffunny Ffrends” is a sprawling Captain Beefheart–influenced jam), but also deeply funkbased (“How Can You Luv Me” and “Jello and Juggernauts” ooze Sly Stone soul). But while Nielson’s new group has afforded him a chance to start out on a new musical path, some old habits seem to die hard. “We did some psychedelic augmentation before a show in L.A., and afterward we smashed a guitar, smashed some bottles,” says Nielson. “It just seemed like the right thing to do.”