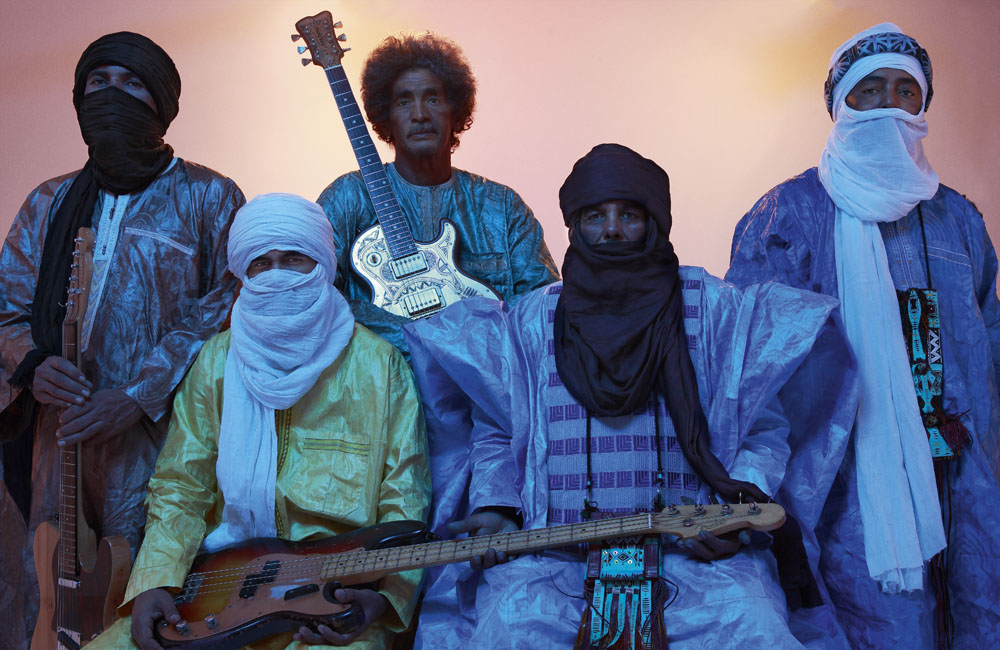

Tinariwen

FROM LEFT: ELAGA AG HAMID, EYADOU AG LECHE, IBRAHIM AG ALHABIB, HASSAN AG TOUHAMI, AND SAID AG AYAD IN PARIS, NOVEMBER 2016. GROOMING: CORINNE FOUET/AIRPORT AGENCY. SPECIAL THANKS: PIN UP STUDIO.

“There is seemingly nothing in the desert, just miles of desolated land and unbreakable silence, yet the eyes of the world are always upon it, fighting to control its hidden resources,” says Eyadou Ag Leche, bassist of the band Tinariwen and firsthand witness to the conflicts for oil, gas, and other primal goods that have taken place on the fringes of the Sahara since, well, forever. For the members of Tinariwen (which translates as “deserts” in the Tuareg dialect Tamasheq, as in “the boys from the deserts,” as they were first known), the Sahara has a different meaning: it’s freedom, it’s home, it’s la maman, as they say in French. It is from the desert that the traditionally nomadic Tuareg musicians, even when far from their homeland in the mountain range between northeastern Mali and southern Algeria, which has lain in an extended state of emergency since last July, feel their sense of belonging. “They can close the frontiers and massacre our people,” says Ag Leche, “but they can’t kill the music, they can’t take the music away.”

On the contrary, Tinariwen’s bluesy, incantatory, and politically charged music has, since the band’s formation in 1979, helped to bring global attention to Mali’s sociopolitical issues and the rights of the Tuareg community—despite being sung only in Tamasheq. As Ag Leche says, music, like the desert, cannot be stopped or contained, crossing boundaries and languages, appealing directly to the soul of people. “We sing about love, our people, and nostalgia,” he says. “We call nostalgia assouf, and that’s what defines our sound.”

In their present elective exile, following a failed attempt in Mali to create an independent state for the Tuareg community and the subsequent backlash by the government there making it inhospitable, the band recorded their new album, Elwan (Anti-), in two different deserts—part in California’s Joshua Tree and part in M’Hamid El Ghizlane, an oasis in southern Morocco near the Algerian frontier. And beyond its dusty, percussive, hypnotic ode to Tuareg spirituality, Elwan, with its global inflections and appearances by Matt Sweeney, Kurt Vile, Alain Johannes, and Mark Lanegan, is intended as something bigger, as anthem and solace for everyone forced to live far from their home: “Because,” as Ag Leche says, “contemporary societies are made of expats. And our commitment is to campaign for peace and rights, through art—as should be the aim of all creative people; that is the role of the artist in our global society.”