The Misshapes’ Next Step

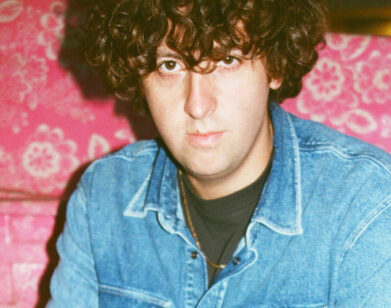

ABOVE: THE MISSHAPES (LEIGH LEZARK AND GEORDON NICOL). PHOTO COURTESY OF INEZ & VINOODH.

The world of sound design and production is nothing new to Geordon Nicol and Leigh Lezark, collectively known as The Misshapes. After meeting in 2003 as college students, the pair, along with Greg Krelenstein, founded one of New York’s most notable dance parties in the last two decades. As celebrities and downtown “It kids” clamored to get through the front door of 21 Seventh Avenue, however, Nicol and Lezark were already planning The Misshapes’ next steps, which included an eponymous stylebook with an introduction written by Vogue editor Sally Singer. They soon found themselves soundtracking runway shows and DJ’ing after parties for designers like Jeremy Scott, Karl Lagerfeld, and Zac Posen.

The most recent step for The Misshapes was creating a film’s score. Nicol and Lezark joined Academy Award-winning documentary filmmaker Charles Ferguson for his latest release, Time To Choose, a film focused on climate control. Just as they work with designers and stylists to create unique atmospheres, Nicol and Lezark collaborated with film editors and cinematographers to highlight emotions within the film as well as its stunning imagery. Last week, just before release of Time to Choose, we spoke with the pair about this endeavor, how sound design works, and why Ferguson’s film on climate control is different from the rest.

MATHIAS ROSENZWEIG: Before becoming involved with Time to Choose, did you know anyone working on the project?

GEORDON NICOL: Not really. We didn’t have any relation to the director, Charles Ferguson, prior to this. The way that we ended up working together is that he had come to fashion shows we were doing sound design for and he really liked the music we put together.

LEIGH LEZARK: And he didn’t want to use a Hollywood type of music supervisor.

ROSENZWEIG: Can you tell me the difference?

NICOL: There are sound designers and then there are music supervisors. Sometimes they’re different, but for this movie we were both. On his previous film, [Ferguson] used a composer and a music supervisor, and the music supervisor was sort of like a Hollywood supervisor. [Feguson] just didn’t like the process of working with him. He wanted someone who was more heavily involved from start to finish be a part of the process—from when they started editing the film through to the finish.

LEZARK: So we were working with him pretty much since the beginning.

NICOL: He wanted someone to bounce ideas off of, because, from the beginning, it was this abstract idea of what he wanted and he wasn’t sure what direction they wanted to take the music in. The film is shot all over the world and in multiple countries, so in the beginning I think he was approaching it as more of a nature documentary, where it was really region-specific music. We wanted to explore the instruments from those areas, whether it was Africa, South East Asia, or anywhere.

ROSENZWEIG: Was that a big learning experience for both of you?

LEZARK: Since we travel all over the place, yes, it was learning, but we already had such a wide library from visiting different places.

NICOL: When we were meeting with [Ferguson] about doing the project and coming on board, he spoke to us about his experiences traveling around the world and working the different fashion weeks that we’ve gone to, like in Jakarta, Indonesia, Beijing, and Buenos Aires—we’ve gotten to work with different designers in those places. It built in the idea that we have experience interpreting different designers’ visions or stories on the runway from different parts of the world. We had a breadth of knowledge around the different places that he had filmed in, so it kind of came naturally to us.

ROSENZWEIG: Do you think doing sound design for a documentary in particular is more challenging than, say, a screenplay?

NICOL: With this type of film, you have a difficult task because you’re not telling this film from start to finish, really. You’re telling really short stories in a very brief amount of time, and you might only have 10 seconds to convey something. So it’s very fast paced and it’s more about information than it is about an emotional experience. There are emotional experiences, like when the guy in the coal mine dies, or when the woman is telling the story about her brother dying of cancer. So there really is a balance between both of those things.

ROSENZWEIG: Can you describe the process of actually creating and orchestrating the music we hear in the film?

NICOL: We worked for the summer in L.A. in a studio and we brought in different musicians—pianists, guitarists, string musicians. We would bounce ideas around and figure out whether it was the right sound. We’d ask ourselves, “Can we source something that’s an organic sound and transform it into something that would be really interesting for the film? Maybe something will work with this Phillip Glass piece that we’ve licensed…”

ROSENZWEIG: The idea of blending organic sounds with arranged music and actual instruments—was this totally new to you?

LEZARK: When we’re doing the runway music, we get to do things like that a lot.

NICOL: We worked with a designer before who had this home video of her children at the beach. In the background of the video there was this sound that she said was the inspiration of a memory or something that evoked an emotion in her. She wanted us to draw inspiration from that, so we created a whole sound for her show based on the video. So we’ve dabbled in this already, but in a different medium.

ROSENZWEIG: Apart from that particular designer, what is the process usually like when coming up with audio concepts for a show?

NICOL: When we go into a meeting with a designer for a runway show, a lot of the time we start with their inspiration, so it’s a process with them. You go from the initial meeting, wherein you get their perspective on what the show’s about to seeing the collection being made, the mood boards, meeting with the stylist—all of those elements are taken into consideration to tell the story. Sometimes it’s really deep and emotional or conceptual and sometimes it’s straight up a party. It depends on the designer you’re working with, but either way, you’re telling a story that has some kind of narrative to it. In talking about that process, I think Charles found it appealing that we were very hands-on in trying to interpret whatever the designer’s vision was. That’s what ended up happening with him as well.

ROSENZWEIG: Moving back to the world of sound design for film, do you think this is something you’d like to explore further, perhaps with screenplays?

LEZARK: I think we definitely would be interested in doing scripted films. We want to be doing more film work. We had such a great time. This process was very educational, but it was fun.

ROSENZWEIG: Were you able to learn from anyone specific who scores films or does sound design?

NICOL: We really look up to Michel Gaubert. He’s the runway master. He’s iconic. He’s been around from the ’80s. We were really lucky to work with him on Jeremy Scott’s show. He’s taught us a lot. It was great seeing him go from runway sound design to doing all these Chanel films that [Leigh] was in, which was inspirational.

ROSENZWEIG: Could this become more of a focus than DJ’ing?

NICOL: We’ll continue DJ’ing. That’s our main job. We sort of know our year in terms of where we are. It’s like, New York Fashion week, London fashion week, Milan, and Paris, and then beyond is Moscow, São Paulo. In the off times it would be great to do a film. It was an amazing time spending the whole summer in L.A. and waking up to work with different musicians. From all of the experiences DJ’ing and partying, we’ve met so many different musicians that we’ve been able to work with. On this project, we reached out to different people that we’ve worked with over time, being like, “Hey, will you come do this classic guitar freestyle?” That kind of stuff was fun.

ROSENZWEIG: Did you learn about how to be more environmentally friendly from the film?

LEZARK: I think that living in New York, you inherently have a bit of a more open mind to all issues. We always had an idea of what we could do to help—recycling, I don’t eat meat—and afterward, it just grew.

NICOL: I can tell you that going into this project the appeal to me was more the creative side of it. But as we became more involved, it became more political and about social awareness for us. Honestly, before we started working on this, I was fine not recycling. And I can relate with people, especially in New York, it’s very hard to apply the things that we’re talking about in this film—solar and wind energy options and recycling. I’m never going to be a vegan, and I love meat, so that doesn’t apply to me. But seeing this film and having a better understanding of all aspects of how I can go greener and cleaner has helped me on an every day basis. You know, now I do recycle.

LEZARK: Turning off all the lights and unplugging things. It goes a long way. The littlest things help more than not doing anything at all.

NICOL: Going electronic on your bills is such an easy thing you can do. I totally get it—people get annoyed by hearing some preachy people talking about these issues—but there’s a lot of value in educating yourself and understanding better.

I think this election has brought that out, too. One part that got cut out of the film is when a congressman brings a snowball and says, “climate change is a myth,” and throws it. It’s scary to think that there’s a large contingency in this country that really doesn’t want to acknowledge scientific facts or understand how this could really affect people. I don’t think people realize the natural disasters that can happen, whether it’s Katrina or the droughts in California. If you’re not already being affected in an extreme way, you’re going to be.

LEZARK: People think that by the time the world is in dire need, they’re going to be dead. But their kids may not be and their grandkids may not be, so it’s very important. If we have the technology, we should use it now.

ROSENZWEIG: How hopeful are you that the average person will be willing to pitch in and help if, to your point, there are so many people refusing to acknowledge the imminent threats?

NICOL: I think people are moving in a better direction and understanding what they can do. A lot of people think this is someone else’s problem, or it doesn’t really register as something that you can affect in your day-to-day life. If nothing else, just voting for a candidate that supports policies that acknowledge climate change helps.

If anyone can have a takeaway from this film, it’s that you don’t have to do all of these things. You don’t have to be the greenest, cleanest person. Just do at least one thing, no mater how small it is. Educate yourself and be aware of how you’re interacting with the world around you and how you’re choosing to live.

ROSENZWEIG: This isn’t the first film about climate change. What makes it special?

NICOL: If you look at climate films, or films that relate to climate issues, like An Inconvenient Truth or Food Inc., they’re talking to you about the problems from a perspective that’s like, “These are all the negative things that are happening.” They don’t talk about the ways that you can fix the problem or the path to change. What’s great about this film is that there’s a campaign happening in conjunction with the release on TimeToChoose.com, where they offer the most comprehensive source outlining the path to change on any level. On solar, on recycling, on keeping organic—literally on any potential aspect that affects the climate challenge. I would say the film is a solutions-based climate change film and that’s what sets it apart.

LEZARK: It’s very inclusive and mobilizing everybody. It’s not just for one specific industry; it’s for all of the industries—oil, food, and so on. This film doesn’t turn you off. It really tells you that you can do this, this, and this to help.

NICOL: One of my favorite parts of the film was in Kenya and Nigeria where they’re showing how much of a difference a solar panel can make. Like a small family in Africa, putting a solar panel on their roof gives them heat, hot water, electricity, and light so they can study and can show their kids educational programs on TV.

TIME TO CHANGE IS OUT NOW. FOR MORE ON THE MISSHAPES, FOLLOW THEM ON TWITTER.