The Black Keys

We could do whatever we wanted. It wasn’t about trying to impress anybody, because there was nobody there to impress.DAN AUERBACH

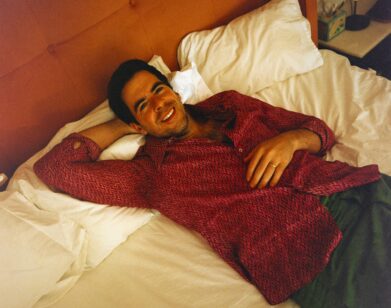

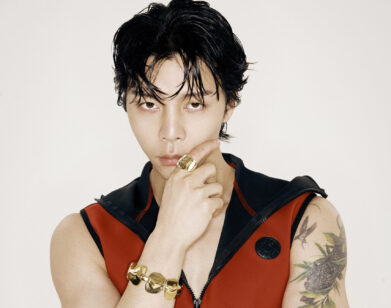

As people, The Black Keys are a study in contrasts: Guitarist-vocalist Dan Auerbach is gruff and guardedly wry, while drummer Patrick Carney is more voluble and outwardly enthusiastic. But together they make up one of the biggest, most universally beloved rock bands-and unlikely pop phenomena-in music today. Auerbach, 32, and Carney, 31, first joined forces in their hometown of Akron, Ohio, as a couple of indie rock-obsessed teenage basement punks hopped up on the primal blues of Junior Kimbrough and Howlin’ Wolf. On early records like 2002’s The Big Come Up and 2003’s Thickfreakness, the duo worked up a rootsy, distorted mayhem that was all raw power and soul; but as they matured, their music grew more assured. They also began an association with Brian Burton, better known as producer-sage Danger Mouse, who collaborated with the band on their fifth effort, Attack & Release (2008), as well as “Tighten Up,” the lead single off its follow-up, Brothers (2010), a supple, groove-filled album that would prove The Black Keys’ breakthrough. Brothers not only entered the Billboard album charts at No. 3, but went on to win three Grammy Awards, consummating the Keys’ full-fledged emergence from the indie-rock underground. Musically, the pair has remained adventurous, even wading into the gritty waters of early-’90s East Coast hip-hop with their ongoing Blakroc project, unveiled for the first time in 2009 on a record featuring collaborations with Q-Tip, Mos Def, and RZA and Raekwon of the Wu-Tang Clan, among others. (A follow-up is in the works.)

For their most recent offering, El Camino (Nonesuch), Auerbach and Carney reunited with Burton for an album that is as irreverent, idiosyncratic, and raw as it is catchy and refined-a glammed-up, full-bore descent into ass-moving rock ‘n’ roll that shakes and rattles with aplomb. The record, which was recorded in the duo’s adopted hometown of Nashville and released in December, has already made an even bigger commercial splash than Brothers, debuting at No. 2 on the charts and selling 206,000 copies in its first week. This year marks not only the 15th anniversary of the Keys’ formation, but 10 years since the release of their first album.

I recently caught up with the two at home in Nashville, where they reflected candidly on the long, strange trip that got them to where they are now-further along than they’d ever expected.

MATT DIEHL: You titled your latest album El Camino, which is one of the most badass cars of the ’70s-but then there’s a Plymouth Grand Voyager minivan on the cover. What’s up with that?

PATRICK CARNEY: We were basically trying to make the stupidest record cover of all time.

DAN AUERBACH: We’re idiots . . . Yeah, that pretty much sums it up. Next question.

DIEHL: Really?

AUERBACH: Well, we’re interesting, too—interesting morons. Anyways, el camino means “the road” or “the path.” That minivan was actually our first tour vehicle when we started out 10 years ago.

CARNEY: My dad bought it for me, thinking nothing would come of the band and I’d go back to college. When I sold it, it had 190,000 miles on it.

AUERBACH: We toured in it for two years. The air-conditioning was broken, and we’d drive it through West Texas in, like, 180-degree heat. Then we had a Buick Century where you couldn’t recline the seats at all—12-hour drives and no reclining. Crazy. But that’s been the path. In the beginning, there were two of us, and we basically drove all over the world. Now we’re on our seventh record, and just keep moving forward. It’s been a long road . . .

DIEHL: What are some of the things you’ve discovered along the way that have surprised you?

CARNEY: Everything we do is pretty much an accident.

AUERBACH: It’s just kind of wild. Our expectations were nil. We come from Akron, Ohio, where people don’t succeed at this kind of thing very often—only once every couple of decades or something.

CARNEY: We came from a town where you’re lucky if you get a job at Starbucks.

AUERBACH: We just liked doing music, and if we could make a little bit of money, it was okay. It was better to sit in that minivan, drive around the country, and get paid minimum wage than it was to work in a kitchen and get paid minimum wage. So we just kept doing that, and every year was a little better than the previous one.

Dan’s dad asked us if we ever thought we’d be nominated for a Grammy. I laughed at him for an hour and a half. Patrick carney

DIEHL: How do you think coming from Akron has affected your work? On the one hand, it’s not exactly an international cultural destination. But on the other, it’s the town that has spawned the likes of Devo and Chrissie Hynde . . .

CARNEY: The Midwest breeds funny, eccentric people, to varying degrees. You play shows not because you’re expecting to get a record deal, but to do something fun outside of mowing lawns. Everything else is just gravy . . . Or mustard.

AUERBACH: It’s nice being so isolated—we created our own universe. There was no scene. There wasn’t even a place to play. You don’t get caught up in the whole being-a-rock-star bullshit. That’s easy to do when you’re in big cities surrounded by press and all the other hip bands and whatever. Bands from Akron have a sense of humor and don’t tend to take themselves too seriously. We could do whatever we wanted. It wasn’t about trying to impress anybody, because there was nobody there to impress.

DIEHL: And now you’ve been doing it for 15 years . . .

AUERBACH: It’s absolutely insane. I just watched Michael Rapaport’s documentary on A Tribe Called Quest [Beats, Rhymes & Life: The Travels of A Tribe Called Quest, 2011]. We’ve already been a band longer than them, made more records, and they have a documentary about themselves! [laughs] Every year something crazy happens. I remember playing our first show, and then playing our first show in Europe, and playing Carnegie Hall with Ray Davies, and winning the Grammys . . .

CARNEY: We thought Brothers would do okay. But it exceeded our expectations so much. That said, it’s not like we wanted or expected to win Grammys. I remember driving back from a gig in Toledo in 2002, and Dan’s dad asked us if we ever thought we’d be nominated for a Grammy. I laughed at him for an hour and a half. It was cool, but it was also a major bummer to walk down the red carpet and realize that not a single person there wanted to talk to any musicians—they wanted to see Kim Kardashian. You experience how much the show isn’t about music. I’m still shocked that, like, Arcade Fire was even allowed to play. It doesn’t seem real to have a real band like Arcade Fire at a show where Justin Bieber is just lip-synching.

DIEHL: Your previous album was called Brothers, but I imagine after all that time together, your relationship is more like a marriage.

CARNEY: I think our relationship would be best described as a mixture between Patty and Selma Bouvier from The Simpsons and Erik Estrada and that other dude [Larry Wilcox] from CHiPs. We take turns playing each role.

AUERBACH: We don’t always get along, but who does? We’re around each other more than we are around our own families. We love each other and care for each other, but we’re not up each other’s asses all the time. That’s why we’ve lasted this long.

DIEHL: There’s a game played at bridal showers, where they ask the bride and groom personal questions about the other to gauge how well they really know each other-and I wanted to do that with you. So where did you first meet?

CARNEY: It would’ve been when I was probably 9 years old, just riding our bikes around in our neighborhood during the summertime.

AUERBACH: We’ve known each other since we were little kids. From the moment I started having memories, Pat’s been around.

DIEHL: You lived down the street from each other, right?

AUERBACH: Yeah, but we didn’t really hang out. In high school Pat was a bit of a character, always doing goofy shit and getting put in detention. Before he had his Twitter outlet, Pat was doing other shit to get attention—and it was usually self-deprecating.

DIEHL: It’s good to have a drummer that thinks he’s the front man.

AUERBACH: I guess so. It’s a trade-off . . . I’m certainly not your typical front-man material. Some people love being on stage and really open up, and I’m sort of the opposite of that. I don’t crave the spotlight. I’m still not comfortable even talking on stage.

DIEHL: What’s the last thing Pat does before he goes to bed?

AUERBACH: Uh, tweets something.

DIEHL: Pat, what’s the last thing Dan does before he goes to bed?

CARNEY: Puts on shorts. He always wears soccer shorts to bed.

DIEHL: Do the two of you have a special song that marks your relationship?

CARNEY: “Smokestack Lightning” by Howlin’ Wolf.

AUERBACH: Or something from Safe as Milk [1967] by Captain Beefheart.

DIEHL: Dan, what would you say is your favorite thing about Pat?

AUERBACH: He’s funny as hell.

DIEHL: What would you say is your favorite thing about Dan, Pat?

CARNEY: Dan’s funny, but he’s also a hard worker.

DIEHL: And what would Pat think is your most annoying habit?

AUERBACH: My spaciness.

CARNEY: Sometimes if Dan’s eating something that he really likes, he’ll suck on his fingers. I have a pet peeve about that. And I still don’t like his beard.

DIEHL: What is Dan’s favorite book?

CARNEY: Probably something by William Faulkner.

DIEHL: What is Pat’s favorite book?

AUERBACH: One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest.

DIEHL: What is Pat’s favorite movie?

AUERBACH: Die Hard 3 [Die Hard: With a Vengeance, 1995].

CARNEY: Dan’s favorite movie is Duck Soup [1933] with the Marx Brothers.

DIEHL: What is Dan’s favorite food?

CARNEY: When it comes down to it, Chinese.

DIEHL: What is Pat’s favorite food?

AUERBACH: Swensons cheeseburgers.

DIEHL: Pat, you talk constantly about your fast-food obsession on Twitter.

CARNEY: I’ve spent a lot of time on Wikipedia looking up, like, White Castle and Arby’s. The greatest invention of the latter half of the 20th century was the idea of eating as many small, piece-of-shit burgers as you possibly can. Fast food is the one thing everyone can relate to. It’s depressing, but also interesting, that people desire to eat the same sandwich in every single city in the world. But the biggest bummer is when you see a Subway in Berlin. Just devastating.

DIEHL: You’re so passionate on the topic, you could be the Guy Fieri of fast food.

CARNEY: Oh my god, I could only hope. I follow him closely. He’s one of the most irritating motherfuckers, but you can’t look away. I’m blown away that he has a career talking about how bitchin’ every burrito is, while getting food over his 1999 relief-pitcher goatee. Basically I’m excited to become a 70-year-old man with no taste buds left who only wants to eat mustard.

DIEHL: Coming off the massive success of Brothers, you both relocated from Akron to Nashville. What precipitated that move?

AUERBACH: I moved to Nashville first. Pat was living in New York City and then one day, out of the blue, he was like, “I’m moving to Nashville!” He literally moved right down the street from me. It was really bizarre, but I had a studio built here in town, so we cut El Camino here.

DIEHL: Brothers had more of a groove-oriented, hip-hop feel, but El Camino is more of a primal, manic rock ‘n’ roll rave-up.

AUERBACH: We were listening to stuff from the ’60s, ’70s, ’80s, and ’90s that was inspired by ’50s rock: The Cars, Sweet, The Cramps-stuff like that. Whether they’re more rocking or more glitter, all the songs are sort of dancey. We wanted it to be more up-tempo. We were shocked sometimes at how fast these songs are.

DIEHL: So will the next Black Keys album be incredibly slow?

AUERBACH: Yeah. All dirges.

DIEHL: What do you hope to achieve in the band’s next 15 years?

CARNEY: I’ve learned pretty much everything that I know being in this band. When we started, I was in college getting horrible grades, working at a coffee shop, and mowing lawns in the summer. I never thought I’d be able to play music for a living.

AUERBACH: We don’t have expectations or dreams, because those will always just bite you in the ass. We’re very content with where we are and the speed we’ve been going. The only way we got through was by keeping our expectations very low. We didn’t want to be rock stars. It’s not about success. Whatever happens, it doesn’t matter. I would like to not go bankrupt or get some incurable disease, but other than that, I’m just happy to keep going.