It’s Sufjan Stevens’ Way or the Highway

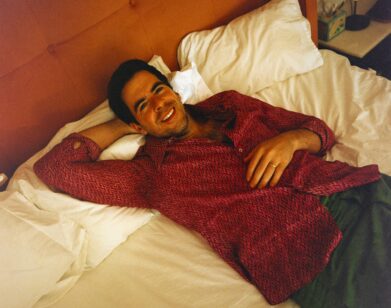

One of the things I like best about Sufjan Stevens is that it feels like he’s from another time or planet. The Brooklyn-based multi-instrumental singer/songwriter—and now comic book writer—comes off as being far removed from the everyday in a way that speaks to either an incredible discipline or admirable disregard. We met at the Diner on 9th Avenue to discuss the release of The BQE, a CD/DVD package documenting the “symphonic and cinematic exploration of New York City’s infamous Brooklyn-Queens Expressway” he debuted with projections, an orchestra, ornate wings, and hula-hoopers over three nights at BAM in 2007. The collection, out via Stevens’s label, Asthmatic Kitty, features the soundtrack, the film footage used in the projections, a 40-page booklet with liner notes and photographs, a “stereoscopic 3-D Viewmaster® reel,” and a BQE-themed Hooper Heroes comic book he worked on with his friend, the illustrator Stephen Halker. The comic follows three extra-terrestrial orphan Heroes, Botanica, Quantus, and Electress, who use hula-hoops “to combat the ‘the Messiah of Civic Projects,’ Captain Moses, and his totalitarian social architecture.”

BRANDON STOSUY: The BQE comes with an essay you wrote. The Asthmatic Kitty website includes explanatory notes. Is it important to you that people understand the background to this particular work?

SUFJAN STEVENS: I don’t want to impose too much information. At the same time this project is so far-reaching and deliberate that I feel a certain anxiety about its success, and its ability to communicate clearly on its own. It’s probably an indication of my insecurity that I’m over-explaining myself. It’s also probably a result of not using a song to express myself. You think it’s too much?

STOSUY: No, it’s generous. In a recent interview recently you talked about encountering too much information in the digital age—”the white noise of information.”

STEVENS: It’s traumatic to meditate on the availability of information through the Internet, or the way we perceive the world as a result. People don’t experience things totally or viscerally anymore. It’s all through representation, be it a record on YouTube or a post on a blog. It seems like The BQE project is different because it’s so physical and multi-disciplinary. It almost asks too much of its listener or viewer.

STOSUY: In an interview with [the musician] Shannon Stevens you said something about modern music being too self-absorbed to be part of daily life…

STEVENS: I don’t know if I can stand by that remark. It was meant provocatively and in the context of our conversation. Shannon’s been out of the music world for ten years, so I wanted her to talk about the selflessness of her life as a working mother … I was feeling privileged and self-conscious about my life as a musician, which feels self-absorbed. I can’t help it—I am a musician. This is what I do.

STOSUY: You mentioned “context.” I wrote you once and asked for a quote about a project you were doing. I posted the quote an hour later and you wrote me joking about how there’s no synthesis anymore — there’s just this quick block-quote turnaround. It must be a little bit nerve wracking to know if you say something publicly, it’ll end up in a place where someone is going to comment on what you just said, even if it’s out of context.

STEVENS: That’s the nature of gossip, really, and the Internet is just one big gossip chamber – that’s why it’s so fascinating and entertaining. It’s a fabulous platform for superficial communication. I feel like the Internet needs to be disarmed in some way. There needs to be a philosophical undermining of the Internet. We take it too seriously and too literally. For a reference we go to Wikipedia, which is full of inaccuracies and misinformation. It’s kind of beautiful—it’s all the product of imagination; it’s not reality at all.

Someone was telling me there was a video of Steve Gadd, or some benevolent drummer, playing on YouTube. It was the most inconsequential upload, but within two or three comments two men were arguing about who was the best drummer in the world and they were planning a place to meet and fight. And it was full of expletives. It seemed strange how quickly you get from this to this. That’s what the Internet cultivates. It’s manic. It’s very strange. I don’t think it’s healthy. They should outlaw posting comments! It’s a bummer to go somewhere to get information or buy tickets and you encounter profanity everywhere you go. I guess it’s like graffiti in a bathroom stall: You just want to take a piss and you’re stuck looking at profanity on the wall or crude explicit drawings.

STOSUY: While we’re being Luddites: I’ve never seen you play any Late Night TV shows. Everyone does those now. You just not want to do them?

STEVENS: I don’t understand why bands do that. It seems really tacky to me. I get asked all the time .Those shows are just promoting insipid comedies. Who watches those shows? And whoever does-I don’t think my music would speak to those people. I don’t even want those people to hear what I’m doing. I think musicians should stay off television generally.

STOSUY: I wanted to talk about the actual BQE, the road. You see it presented via the various super8 projections in the staged piece – the traffic, the landscape around it, the road itself. Have you ever thought about the highway as an information superhighway? To get metaphorical… The highway as this cobbled together imperfect thing?

STEVENS: The information superhighway? [LAUGHS] That term is so outdated! Nobody uses that term anymore.

STOSUY: My dad does.

STEVENS: Well, it’s definitely an artery of information. It’s human beings. It’s goods. My problem with the piece [The BQE] generally is that I could never quite fathom the BQE as an object outside of metaphor. It’s like wanting to see the face of God. I wanted to see it for what it is. The result was this revelation of horror that is nothing really. It’s the first time that I tried to write about something, and felt that the result was meaninglessness, there’s no meaning to it. All the analogies and the metaphors is imposed.

STOSUY: When you were envisioning the BQE was it important that the Hooper Heroes be three females?

STEVENS: Oh yeah, necessary. The BQE is the product of masculine ambition. It’s completely patriarchal—Robert Moses was the Type A alpha male civic engineer. Everything he did with force of will-not that ambition is not feminine. But the Hooper Heroes are a relief to the concrete linearity of the expressway and the scenes of urban renewal from the ‘50s. They’re beauty and transcendence and insular introspective thought. We always use women to represent these enlightened abstractions, like Justice and Lady Liberty. I don’t know what a feminist critic would say to that. Granted there are male Hoopers—Barnum and Bailey… We’re going to kill them off in the next issue [of the comic]. They’re not supernatural, Barnum and Bailey. The girls are supernatural—or they’re from outer space. We wanted there to be a community that’s mixed with celestial immigrant superheroes and human beings.

STOSUY: Will you keep doing issues until the story’s told?

STEVENS: I would love to do it forever. I would love for this to be my full-time job but nobody’s buying it. I went on tour and [the illustrator] Steve [Halker] came on to sell my merch. After a couple shows I was like “So, Steve, how’s it going? Are people buying the Hooper Heroes T-shirts and the comic books?” He was like, “No, they have no clue what it is. They think it’s the opening band, the Hooper Heroes.”

STOSUY: You couldn’t get distribution?

STEVENS: I don’t know how to break into that subculture. No one seemed interested because the comic book doesn’t fit into a specific genre. It’s kitschy and silly and retro and at times esoteric. I think it’s breaking a lot of rules and committing faux-pas, but whatever.

STOSUY: Did you use comics and the ViewMaster, and hula hoop because these things aren’t usually associated with high art, with BAM, with an Opera House?

STEVENS: That wasn’t intentional. But that’s interesting. The ‘50s [when the BQE was built] was the Golden Age of comic books and it was also the creation of the ViewMaster … and even [The BQE‘s] style of music to me feels very Gershwin, maybe a little earlier, the 30s or 40s. It’s very kitschy American and referential to romantic European music. All the styles and all the objects themselves are all very mid-century. To me the project is really dated.

STOSUY: The villain of the comic is Captain Moses, an evil developer. Have Robert Moses’ people contacted you?

STEVENS: I was a little worried when we were making the comic book, because we were depicting Robert Moses as a villain. But he’s a public figure-and worse things have been said. We also don’t see Captain Moses as being completely evil. I think he’s extremely well-meaning and ideological.

STOSUY: As the comic becomes an ongoing project do you think it allows you to make music that’s less conceptual?

STEVENS: The comic book definitely works a different part of my brain. It allows me to think more graphically and more in terms of plot. The comic book seems completely disassociated from music, and I really like that. I’d like to stop writing conceptual albums for a while.

STOSUY: Have you started anything new?

STEVENS: I wrote a lot of stuff that we workshopped on this tour. There’s no theme, nothing keeping them all together. But it’s hard for me to turn away from a broad vantage point. I’ve been looking at all these songs and thinking about they relate. And if they don’t relate I just let them sit on my hard drive; I can’t see them through onto an album.

STOSUY: You’ve been doing these multi-disciplinary projects. Do you see yourself moving into art in a gallery setting?

STEVENS: I feel open to everything right now, to any setting. There was a run of shows with the quartet playing the Enjoy Your Rabbit arrangements, and screenings of The BQE, and many of those shows were in galleries, museums and art spaces. I’ve never been too considerate about the distinction between a gallery and a club and an opera house. We bring misconceptions to these spaces, but those are grumpy, outdated grievances. There is no uptown/downtown conflict of aesthetics anymore. At least, none worth participating in. My only concern about art collaborations is that I never thought of myself as an Artist. My tax forms say Musician/Songwriter.

STOSUY: There is the visual aspect of The BQE.

STEVENS: The BQE is definitely an art piece … So much of The BQE‘s the result of working through the anxiety of playing in the Opera House. Like, how do I live up to the space? But I think most people would rather I just strum the guitar and sing and be myself. I’m terrified of just being myself because I think it’s boring. I know who I really am and I think it’s boring..

STOSUY: Do you think you’re going to do any more State records?

STEVENS: That was all publicity. It wasn’t really serious… I think there’s a risk of becoming a cliché of myself. I would probably do it again, but I don’t need to work on that right now. I’ve been working a lot on figuring out how to sing differently and better. I want to become a better singer. I want to sing out more. I want to me more extroverted, vocally. A lot of my previous records have a real closeness to them-an intimacy with the voice. I want to throw my voice more, I want to manipulate melody more.. I want to be less deliberate and mechanical… I want less melody. I was talking about Jimmy Scott that Jazz singer, Little Jimmy Scott, he’s got just such a beautiful rhythm and his placement of notes in a song and even in these well-known standards they are really deconstructed in a way and subversive.

STOSUY: Is that why these new songs are incorporating different instruments and genres? The ones I saw on YouTube had jazz breakdowns.

STEVENS: That was the result of inviting my friend CJ Camerieri on tour. He’s a trumpet player and he’s been playing around with effects pedals and different equipment… Things turned really jam-y really quickly. It was just like me doing my weird kind of bad guitar solo noise stuff and CJ doing his Bitches Brew stuff through effect pedals and then my bass player, who is this incredibly skilled guitarist, just playing all around us on the bass. He’s playing more notes than anyone else. The whole thing felt like it was from the 70’s, but it was a good exercise for me to deconstruct old forms of the songs.

STOSUY: I was thinking about the idea of silence. In that interview with Shannon you ask, “Does a song have any meaning even it’s not shared?” Silence is almost impossible now. People are so excited to be the first to hear something. If you play a show someone is guaranteed to video tape it.

STEVENS: There’s nothing personal anymore. To me, there is a real sacredness to privacy, especially because we live in an exhibitionist culture. There’s such a magnitude of record taking. It’s so exhaustive. Bandwidth and hard drive space are able to accommodate limitless capacities to take a record of anything and everything. Maybe I do really value the kind of personal-private creative endeavor that’s done in isolation. My Dad used to say that the balance of the world relied on all of the monks who were living outside of society in creative isolation. I don’t quite understand the ascetic life or the private life or the monastic private life. But I definitely understand privacy’s value.