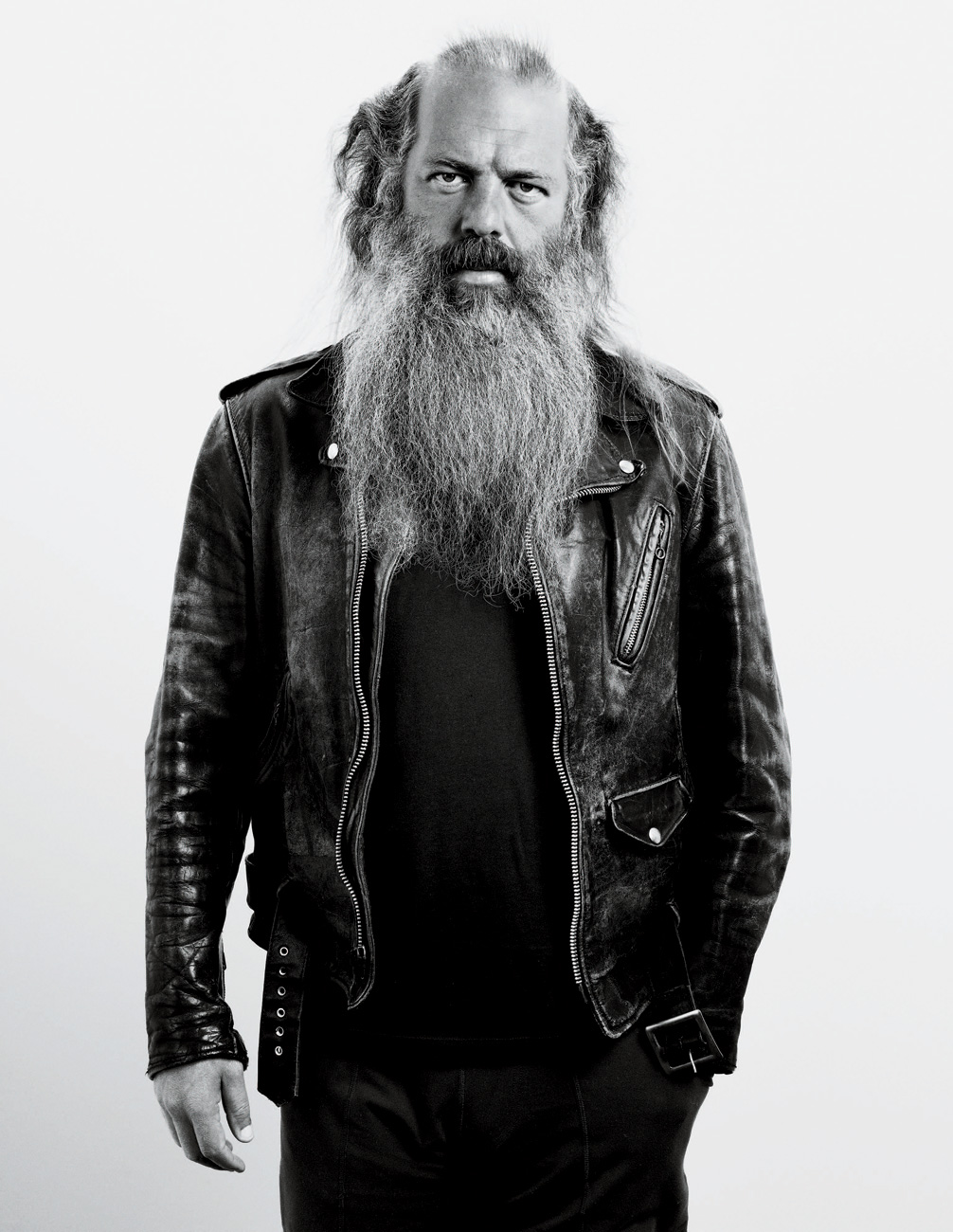

Rick Rubin

The first thing one tends to notice about Rick Rubin is his beard, which is long, full, unruly, and impressive, and more gray now than its original brown. Rubin has had the beard since he was a college kid from Lido Beach, Long Island, playing in an art-rock band called Hose—which is to say, for the better part of the last three decades. And aside from his own spiritual leanings—of which there are many, some of them musical, some of them Buddhist, some of them vaguely New Age-y—it lends him a certain reassuringly mystical quality, so that even if he doesn’t have all of the answers, he at least looks like he might. It all goes a very small way toward explaining why, as a producer of music and maker of records, Rubin has very often been referred to as a guru, an artist whisperer who likes to meditate and play with prayer beads and ask unanswerable questions, when, in actuality, he approaches his work and his purpose more like a searcher than a sage. Rubin’s isn’t a beard of torment, like John Lennon’s, or a beard of excess, like Jim Morrison’s, but rather the beard of a man on a journey—which, if you’re an artist lost in the creative wilderness, is precisely the kind of wizened stranger you want asking you what you’re looking for and offering suggestions as to where you might go to find it.

The story of how Rubin started Def Jam Records with Russell Simmons in 1984, operating the venture out of his New York University dorm room, has gone from legend to lore. Since then he has become one of the most influential producers in the history of pop music, producing seminal hip-hop albums like LL Cool J’s Radio (1985), Run-DMC’s Raising Hell (1986), and Beastie Boys’ License to Ill (1986), and overseeing stripped-down hard-rock reinventions such as Slayer’s Reign in Blood (1986), the Cult’s Electric (1987), and former Misfits front man Glenn Danzig’s semisolo debut, Danzig (1988), changing the face of music forever.

Nevertheless, the list of artists Rubin has worked with since leaving Def Jam in 1988 might be even more impressive, among them the Red Hot Chili Peppers (on four albums, beginning with 1991’s Blood Sugar Sex Magik), Jay-Z (on The Black Album, 2003, which features “99 Problems”), and Justin Timberlake (on FutureSex/LoveSounds, 2006), as well as records by The Black Crowes, Rage Against the Machine, Tom Petty, Mick Jagger, Sheryl Crow, Linkin Park, Metallica, Weezer, and The Dixie Chicks—and, more recently, Josh Groban and Kid Rock. Rubin also famously oversaw the late-career renaissance of Johnny Cash, with the trifecta of American Recordings (1994), Unchained (1996), and American III: Solitary Man (2000); worked on Joe Strummer’s final—and probably finest—post- Clash album, Streetcore (2003); and conjured Neil Diamond’s most critically acclaimed work since the 1970s, with 12 Songs (2005). And for the last three years he has served as co-chairman of Columbia Records, where he has continued to nurture an eclectic group of less-established artists such as the Portland, Oregon, proto-punk outfit Gossip, and the British singer Adele, whose sophomore album is due out this month.

Rubin’s productions tend to be pared-down, potent, and powerful. He goes about making music in the way a perfumer might create a scent—bit by bit and somewhat instinctively, but with a phenomenal amount of know-how. For the artists themselves, Rubin’s production techniques can often verge on self-actualization exercises, pushing them to find the inner them, the more them them—and to look outside of themselves, too, at what they might be or didn’t know they could be—and letting it all flow out from there.

Recently, though, the 47-year-old Rubin has been focused on some of his own self-actualizing. For a long time Rubin’s physique was, for lack of a better term, Rubenesque, but over the last year and a half he has undertaken a rigorous diet-and-workout regimen heavy on fish, protein shakes, and surfing that has helped him shed more than 100 pounds. He recently took a break from working with the Red Hot Chili Peppers on the band’s forthcoming record—their first since the 2006 double album Stadium Arcadium—to sit down with the group’s singer, Anthony Kiedis, to discuss the connection between mind, body, and music.

ANTHONY KIEDIS: I was bouncing on my trampoline yesterdayfor about 25 minutes straight— which I’ve never done in my life. But I started thinking about topics to discuss with you as I was bouncing. One of the things I thought of was a message that Yehuda [Berg, a Kabbalah teacher] had sent me last week on the topic of transformation. He asked, “Why are we here? What the hell are we all doing, running around?” And he said that the reason we’re here is to transform. Then I started thinking of some of the miraculous transformations that I’ve witnessed from my circle of friends. And I thought that your recent transformation is right up there. You are in the midst of one of the great transformations of a lifetime. Do you want to talk about that?

RICK RUBIN: I’m happy to talk about it.

KIEDIS: Because it wasn’t two years ago that you weren’t feeling great physically or emotionally. We talked about it, and I know that you were thinking of ways to approach change. But, I mean, you just got on a rocket and haven’t gotten off. What’s that been like? What happened?

RUBIN: I didn’t have any expectations about what would happen other than just basically giving up control of my life and doing what I was told. That was really the key to the whole thing. In the past, I always thought I knew what was best for me—as it relates to eating, because I really thought I ate healthy. You know, I was vegan for a long time, and I felt like I knew my toleration for exercise, which was not great. But it really was giving up that control to other experts, and doing what they said—even when it sounded crazy and scary—that allowed change to happen.

KIEDIS: I know that you work hard daily, without fail, but what’s your routine like?

RUBIN: Monday, Wednesday, and Friday we do gym training with weights. But it’s different than any weight training I’ve seen before, in that you’re never standing still or sitting on a bench lifting weights. You’re always either in an awkward position or having to balance or having many things going on at the same time. So, if you’re doing an arm exercise, you might be doing a balancing leg exercise at the same time. So you’re very engaged, and I think that’s the thing that has attracted me to this kind of training. It feels like it’s as much mental work as it is physical work. You really have to concentrate. It’s not like being on a treadmill and watching TV and tuning out and just letting the time pass. It really is active, engaged activity. And I want to say it’s difficult, but it’s not always difficult. Maybe challenging would be the word. But in a fun way—like, you feel your body changing, or your ability to do things change. It feels good to try something for the first time and not be able to do it at all, and then to be able to do it a little bit, and then eventually to be able to just do it. It’s a great feeling. It feels like every time one of these new activities comes in, new pathways in the brain are activated, where your brain is able to coordinate the parts of your body. It feels like there’s a lot going on in the body to do this. It’s a complicated set of instructions going on in the body that’s interesting to feel as you gain balance and things like that. I feel like it could lead to some really nice things like surfing and things that I haven’t been able to do before.

I ALWAYS THOUGHT I KNEW WHAT WAS BEST FOR ME . . . BUT IT REALLY WAS GIVING UP THAT CONTROL TO OTHER EXPERTS AND DOING WHAT THEY SAID—EVEN WHEN IT SOUNDED CRAZY AND SCARY—THAT ALLOWED CHANGE TO HAPPEN.Rick Rubin

KIEDIS: But you are in the water on a surfboard?

RUBIN: I’m standing up and paddling on a regular basis. Monday, Wednesday, and Friday are gym days, and then Tuesday, Thursday, and Saturday are days where we do a lot of pool activities—not involving swimming, but all involving weights and holding your breath underwater and jumping and unusual things.

KIEDIS: So basically you’re doing the training of a top-level athlete? I mean, because the guys you’re working with are extremely gifted athletes—the best in the world.

RUBIN: Yeah. I’m doing it on a lesser scale, but following in their footsteps. [laughs] I’ve been very lucky in that Laird Hamilton [the big-wave surfer] invited me to start training with him, and he’s very, very committed to his training—both as a way of life and also to keep himself alive because he regularly puts himself at risk in his job. He wants the most edge against these odds as possible. So it’s really serious training, and I do it at whatever levels I can. It’s just inspiring being around people who are excited about what they’re doing. It’s like he doesn’t exercise with the idea, Oh, I have to get this done. He exercises with the idea of how interesting this is, and how much fun it is and how lucky we are to get to be able to do this with our lives. So it’s a really uplifting practice that I’m really enjoying.

KIEDIS: Have you noticed a change in your outlook toward creativity since you have become highly physical?

RUBIN: I’d say probably the biggest change is that I have more energy, and that probably is a good thing. And maybe I’ll think about things from different angles. But I feel like my commitment to creativity has been the one thread in my life, really. All I’ve had is an interest in watching things unfold creatively, I guess. That’s the best way to say it. And I don’t really know how that has changed through this process. [pauses] Hard to say.

KIEDIS: Okay, I’m going to give you some ages, and I would like you to tell me what music you were listening to at that point in your life. Okay. Five years old. What were you listening to when you were 5?

RUBIN: Probably The Beatles and The Monkees. I would say maybe even other British Invasion music as well, like Herman’s Hermits, the Dave Clark Five—all the British Invasion music. I remember having singles and really liking that music especially.

KIEDIS: Okay. Ten years old?

RUBIN: At 10 I think I stopped listening to music and was listening more to comedy albums by then.

KIEDIS: Anybody you liked in particular?

RUBIN: I liked George Carlin, Richard Pryor, Cheech and Chong, Bob Newhart, Bill Cosby, David Steinberg. There was a guy named Chris Rush. Those are the ones I can think of.

KIEDIS: Cheech and Chong. I don’t know if they’re considered in the tier of the comedy supergreats, like Richard Pryor. Are they?

RUBIN: I don’t know.

KIEDIS: But I will say that I think about them a lot, and they continue to make me very happy—just the whole entity. They were great pioneers. If you look at all of comedy that has come since then to do with sort of dropout, weed-smoking culture, it’s all very based off of Cheech and Chong.

RUBIN: It is. And they really continued that tradition of comedy teams.

KIEDIS: I mentioned Cheech and Chong to my nanny the other day, just to see if they were still out there in the air. She had no idea who they were. She certainly knows about Dazed and Confused [1993] and Pineapple Express [2008] and all of that stuff, but she doesn’t really know where a lot of that came from.

RUBIN: There was also Monty Python, who weighed heavy on me in that time. I still really love Monty Python. And I love Steve Martin.

KIEDIS: All right. Fifteen?

RUBIN: At 15 I started listening to hard rock and heavy metal, but I would say it was more hard rock because I liked Kiss, Aerosmith, Ted Nugent, and eventually AC/DC. That was sort of the music that brought me back into music after comedy. That was the next thing that spoke to me.

KIEDIS: Twenty?

RUBIN: At 20, I was more punk rock—or probably the end of punk rock for me then. So it was The Ramones, The Clash, Ian MacKaye’s group [Minor Threat], Black Flag. In between 15 and 20—probably at around 17—my interests switched from hard rock to punk rock. And then by 20 they were circling out of punk rock back into Black Sabbath, Led Zeppelin, the stuff that I didn’t get to when I was younger. When I was in college, I started listening to those bands.

KIEDIS: I had a similar experience with Led Zeppelin. I didn’t really get to Led Zeppelin until I was in my 20s.

RUBIN: Until after punk.

KIEDIS: Yeah. Because everyone that was into Led Zeppelin when I was in junior high school . . . they weren’t my people.

RUBIN: Same.

KIEDIS: And so I just kind of had to ignore the whole thing. I saw the Led Zeppelin T-shirts and I was like, “You’re not my people. I can’t go there.” But, boy, was I mistaken, because I really discovered a treasure trove. It happened with a lot of things like that for me, where I was just too arrogant and pigheaded when I was younger to listen to what was good, just because I didn’t jibe with the people who were into it. So what were you into at 25?

RUBIN: At 25 it was probably the tail end of my hip-hop period. I went from listening to Led Zeppelin and Black Sabbath and that music into hip-hop really deeply. That was the real focus of my musical interests at that time. Although, while I was listening to hip-hop, I was still listening to Black Sabbath and I was still listening to James Brown and I was still listening to things outside of hip-hop. But the dominant thing I was listening to at that time was hip-hop.

KIEDIS: What was the first hip-hop record that you ever heard?

RUBIN: The first thing I ever heard was “Rapper’s Delight” [The Sugarhill Gang, 1979]. I’d heard that while I was still in high school.

KIEDIS: What was the hip-hop record that you heard that made you say, “I have to make a record”? What was the one that compelled you to jump out of the bleachers and onto the playing field and actually make a recording?

RUBIN: I don’t know that it was a record that did that. It was more what I saw that drove me to take that step. I used to go to this place called McGill’s, which was a reggae club, and on Tuesday nights they had hip-hop night. They’d have DJs from the Bronx come, and rappers would perform, and I would go every Tuesday night. The club got kind of an eclectic punk-rock audience, and I would hear that . . . I just remember the energy at that club. And then, in those days, you could buy every hip-hop record that came out. Maybe three 12-inches came out a week, tops. And I heard that there was a difference between the records that were coming out and what it was really like in the hip-hop clubs. So it was more my experience of the hip-hop clubs that made me want to make records that were really more documentary style, as a fan. I wanted to make records that sounded like the music at the hip-hop clubs, which was different than the records sounded, because the records sounded more produced, almost like R&B records or disco records, but with guys rapping on them. In the clubs it was all much more raw.

KIEDIS: At 30 years old?

RUBIN: I’m going to guess I was back in The Beatles by 30. It had come full circle. The Beatles and then maybe The Doors. I went through a heavy Doors phase again at one point in time. And then around that time N.W.A came along. I really liked N.W.A. I had kind of left hip-hop behind at that point, and N.W.A was the first thing in hip-hop after maybe three or four years that got me excited about it again. I just felt like, “Wow, this is something I haven’t really heard before.”

KIEDIS: I remember the day that record came out.

RUBIN: Straight Outta Compton [1988].

KIEDIS: Yes. I was on tour in Florida—oddly enough, with Murphy’s Law, a New York band— and [John] Frusciante and I ran from wherever we were to the local record store, got it, and listened to it every day for a very long time. Let’s skip forward to now. What’s the music that’s in your life now that’s turning you on?

RUBIN: It’s pretty eclectic. I would say more than anything I listen to a combination of old psychedelic music, classical music, and jazz, and then, as far as current music being made, I really like some of the dance music. I really like LCD Soundsystem, Crystal Castles, things like that.

KIEDIS: I hear you on both counts. I popped in an old LCD Soundsystem record for my last bike ride. I’ve acclimated to the music-while-exercising thing. It’s probably one of my favorite things to do—to pedal down the PCH [Pacific Coast Highway] looking at the waves coming in—and I just felt such a kinship with that strange man from that strange land just in his house making songs. I just connected with him. And, as you know, Crystal Castles stole my heart a couple years ago. I haven’t really been as romantically inspired by a record since.

RUBIN: I don’t know if I’ve been, either.

IF ALL I EVER DID WAS MAKE HIP-HOP RECORDS, IT WOULD GET OLD. I THINK THAT BOTH MY ABILITY TO DO IT AND THE INSPIRATION THAT I BRING TO IT WOULD WEAR OUT.”Rick Rubin

KIEDIS: I know you work on a lot of records at a time. You take on a lot of projects. When you decide to work with an artist, is it because you love that artist? Or do you sometimes work with artists who you do not love, because you feel like there’s something that can be developed?

RUBIN: It usually is more about how I feel about the people personally—like, if they seem like they’re people I’d like to spend time with and be around. That probably counts for more than their hard work. I really like the challenge of working with different kinds of music. I feel like my role is really like a coach, so I feel like I can do my job for different kinds of music that may not necessarily be what I listen to. But it really depends on the project. Like, when The Dixie Chicks asked me to make a record with them, it was fun because I’d never worked with female, harmonizing, country artists before. It was really different than anything I’d done. So it was a fun challenge. I hadn’t really listened to their music before we worked together, but it was a great experience and I enjoyed getting to work with them, and I got to learn new things about music. Same thing when I worked with Josh Groban. Working with different artists makes for interesting experiences. I feel like they help me at my craft by helping me push the boundaries of what I’ve done. If all I ever did was make hip-hop records, it would get old. I think that both my ability to do it and the inspiration that I bring to it would wear out. But continuing to edge into different genres and experiment in different kinds of music is really a kind of training. It forces me to think about things and approach things in new ways, and then I can apply the things that I learned in one genre to another. It all just makes me more versatile in the craft. And I like the stimulation of coming into a project where I really don’t know anything about anything and having to learn about it and understand it.

KIEDIS: You also run a record company.

RUBIN: Yes. I’m involved in the record business as well. [laughs]

KIEDIS: You’re involved. I don’t even know what words to use to talk about the music industry anymore. But the business has changed a lot— the methods of releasing music.

RUBIN: But it hasn’t changed as much as it needs to, because the world is different from the way record companies are set up.

KIEDIS: Personally, I am stuck with one foot in the past and one foot in the present. I still have CDs that I listen to on my motorcycle when I go to rehearsal and I feel very connected to them. I still play vinyl. My son and I will sit there and listen to Devo records and dance around. And it all sounds so wonderful to me because there is something physical about it—it’s wax and vinyl and needles and vibrations, and it all sounds really good to me. But then I also have iPods and Sonos and all of these other new ways of accessing anything I want to listen to any time of the day or night. So I can’t really figure out what to do. I feel like I’m trapped in all of these many different limbos. Like, I want a record, but there’s no record store to go to, so how do I get my music? Do I download it? What do I put it through? Is it going to sound without balls because it’s all digital? So, Rick, as somebody who is involved in this other side of things—this putting out and releasing of music—where the hell is this whole thing going? How are you going to help us out, here?

RUBIN: It’s funny, because there are all these different, opposing forces at work. The old record company system is very rooted in the way things used to be and is resistant to changing. So the way we listen to music—and the music industry itself—could have already been transformed, but they’ve been holding on tooth and nail to the way it used to be. And unfortunately for them, they’re losing the battle. It’s also unfortunate for music, because everything could be so much better sonically and easier to hear. The technology is getting better. There will be a day when you’ll be able to hear any music you want, anywhere you are, on demand, in a quality that is as good as when it was made. Things are moving in that direction. They’re not completely there yet in terms of quality and availability and wireless broadband capacity, but things are heading in that direction.

KIEDIS: Is there anyone who you’re really hungry to work with someday, who you haven’t?

RUBIN: I guess Paul McCartney would be high up on the list, just because he has made so much music that has moved me for so long, and he’s maybe the greatest songwriter alive today. It would be great to be able to talk about music with him.

KIEDIS: Of the people that you have made records with, is there anyone, either on a musical level or on a personal level, who you would describe as the epic peak of your experience?

RUBIN: It would be hard to do that. I get to work with really cool people.

KIEDIS: Well, when I think about you and your career, from my perspective . . .

RUBIN: From your close perspective. [laughs]

KIEDIS: I think a lot about Johnny Cash.

RUBIN: Incredible.

KIEDIS: I really think about Johnny Cash because he’s on that weird level of artistry that goes back to when the beginning of all the music that we know and listen to was being invented in America, and he had such an interesting trajectory as a human being and as an artist. And then for you guys to cross paths when you did, and accomplish as much as you did together . . . It was a resurrection. Not that you resurrected Johnny, but together you experienced a resurrection that would re-gift the world at large with endless joy.

RUBIN: Amazing when that happened. It was amazing. I was just lucky to have had that guy in my life. I mean, we spent time together and he was humble and smart and spiritual. Incredible guy. Incredible. We’re all really lucky to have had time with that guy.

KIEDIS: So just to put this into a little bit of perspective, just as far as you and I are concerned and our relationship, would you be willing to recount the first time that we ever met?

RUBIN: The first time we ever met was at a rehearsal studio that was part of Capitol Records. It wasn’t in the Capitol building. It was EMI on Sunset. I think it was the original lineup of Chili Peppers because I know that Hillel [Slovak, the group’s original guitarist] was there. [Slovak died from a heroin overdose in 1988.]

KIEDIS: Hillel was there. I think Cliff [Martinez, the group’s one-time drummer] may have still been in the band. It was right on the cusp of our drummer quitting and our original drummer, Jack Irons, coming back. But Hillel was there, for sure.

RUBIN: I remember it being strange for me. I remember a dark feeling when I was there. It was something I didn’t understand. I didn’t understand what was going on in that room—and it had nothing to do with the music. It had to do with an energy of mistrust or something between everybody in the room. And it seemed scary, like, “Something is going on here that’s bad, and I don’t know what it is, but I don’t want to be around this. . . .”

KIEDIS: Yeah, that first meeting would have been around 1985 or 1986. I think that you literally walked in on one of our lowest, darkest, most drug-addled points. To me, it was odd—and remarkable—that we were still showing up and practicing, because both Hillel and I were very involved in pursuing self-destruction and copious consumption of narcotics to the point where you didn’t know what was going on when you walked in that room. Were you with Adam?

RUBIN: I was with Adam Horovitz [of Beastie Boys].

KIEDIS: We were really out of it. I think about that day when we met, when we were both in real different places, and then we kind of realigned years later and just started working together. And now we live a block away from each other and we get to go surfing together.

RUBIN: Amazing how life has unfolded.

KIEDIS: Shocking.

RUBIN: I remember being really excited when we did get to work together, because I was new to L.A. at the time. I was living in New York and I had just moved to L.A., and I remember being excited because our relationship felt like part of my introduction to the city. Even though I’d been to L.A. before that, I’d always felt very much like an outsider, and spending time with your band allowed me to see more of an insider view of L.A., and I really enjoyed it. I really enjoyed that experience of getting to feel what it’s like to be local.

KIEDIS: Now you’re very local.

RUBIN: I’m local.

KIEDIS: Part of the fabric.

RUBIN: Yes.

KIEDIS: All right, I am going to take my son to visit his grandpa.

RUBIN: And I’m going to go to the gym.

Anthony Kiedis is a founding member and the lead vocalist of the Red Hot Chili Peppers.