Remembering Chris Cornell

Last night, after performing in Detroit with his reunited band Soundgarden, singer, songwriter, and guitarist Chris Cornell passed away at the age of 52.

Alongside Nirvana and Pearl Jam, Soundgarden, which was founded in 1984 and fronted by Cornell, was an integral part of the Seattle grunge music scene in the early ’90s. Though the band broke up in 1997 after five studio albums (three of which went platinum) and two Grammys, they reunited in 2010. In the intervening years, Cornell released several solo albums and joined Audioslave alongside former Rage Against the Machine members Tom Morello, Tim Commerford, and Brad Wilk.

In memory of Cornell, here, we revisit our March 1994 profile on Soundgarden.

Soundgarden

By Steven Blush

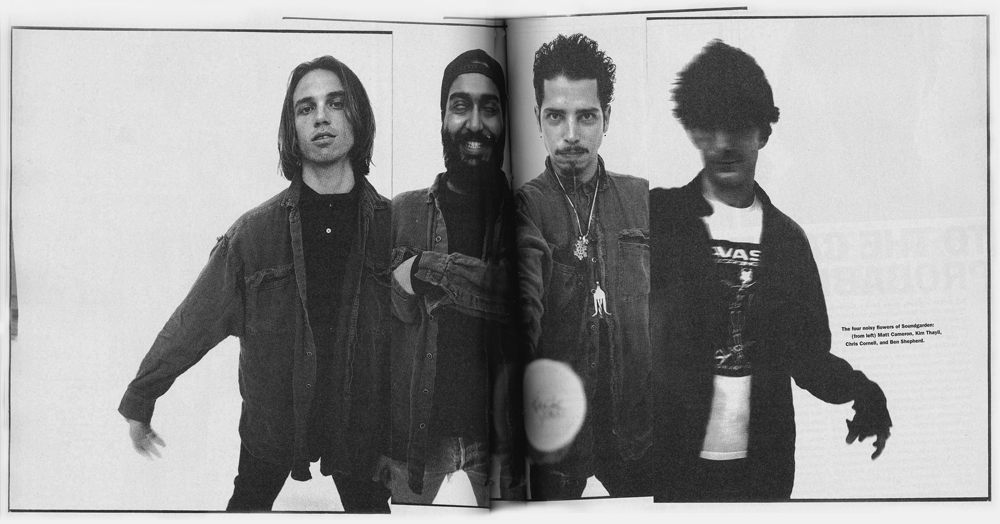

To the casual pop aficionado Soundgarden are probably just another overhyped settle grunge band. But to the initiated, these Pacific Northwest nomads are the founding fathers of a trendy regional style: a Black Flag/Black Sabbath punk-metal fusion, which has set the aural standard for juggernauts like Nirvana, Pearl Jam, and Alice in Chains. The first flannelled Emerald City outfit to ink with a major label, Soundgarden—vocalist Chris Cornell, lead guitarist Kim Thayil, drummer Matt Cameron, and bassist Ben Shepherd—could have easily cashed in on Cornell’s rock-jock good looks for an orgasmic 15-minute joyride. But despite Cornell’s wildly popular Temple of the Dog side project, his bit part in Cameron Crowe’s film Singles, the band’s ’92 Grammy nomination, and the inclusion of a (butchered) version of their political-incorrectness anthem “Big Dumb Sex” on Guns N’ Roses’ recent punk-tribute album The Spaghetti Incident?, Soundgarden seem doughtily disconnected from the traditions of show biz. Some may call them holier-than-thou gnarly-dude prima donnas, but Soundgarden are genuinely gawky, overly sensitive, punk-weaned professionals. And while this antistar attitude hasn’t always served them well commercially, Soundgarden are perhaps Seattle’s most-respected rock outfit.

This month Soundgarden will unleash their fourth album, Superunknown (A&M). It is easily their finest studio effort to date: loud, proud, and pleasantly devoid of pomp or circumstance. Propelled by Thayil’s brooding but powerful guitar mantras, and the machine-hard rhythm section of Cameron and Shepherd, Soundgarden prove their place as leaders of the new school. Meanwhile, Cornell has cut his fabled flowing locks and chucked his trademark flannel, but never fear, because the song remains the same.

I spent a few hours with Cornell and Thayil at A&M’s posh, overstocked conference room, where we burned incense and hurricane lamps and discussed what it takes to be serious musicians on a sometimes-frivolous musical frontier.

STEVEN BLUSH: You were probably the first band for which the term grunge was coined. What do you think that term represents now?

CHRIS CORNELL: I think it’s come to mean alternative, in a way. I saw a grunge compilation album with a picture of a flannel shirt on the cover, and only half of the bands were from Seattle. Now it seems like that word embraces almost anything that’s popular. You can watch a Tony! Toni! Tone! video and most of the people in there are wearing their version of grunge fashion. They look like they’re from Seattle, yet it’s an R&B song. So grunge has become an easy marketing reference, a handle for people who aren’t particularly interested in listening to music or in what it is that the bands do.

BLUSH: How have you tried to distance yourself from that cliché?

KIM THAYIL: It’s hard. But now we avoid wearing flannels; that’s the only way. The other thing is to not have dreads.

BLUSH: Unlike many other Seattle bands, you’ve never played the rock industry game and haven’t achieved the multiplatinum successes that many of your peers have enjoyed. Do you ever regret that decision?

THAYIL: We’re happy with what we’ve achieved. Every record we’ve made has furthered the growth of our line of success. It’s never disappeared or gone backward: each record sells more, each tour is bigger.

CORNELL: If you sold a million records, the only way you could be disappointed is if the guy down the street sold seven million. But you’ve got to start dodging bullets once you’ve sold that many records, because everybody wants to kill you. We’re not in that position. We can still be very successful and not have to worry about wearing bulletproof vests. When we were starting out, we were the biggest draw and the first band to get major-label attention, which was unheard-of at the time. Later, people would come up and say: “There’s this new band and we think they’re pretty good. They might be cooler than you.”

THAYIL: It’s like the challengers to the throne. I’m not afraid to say that there definitely is a Soundgarden Lite that has been presented and has had success. But a Soundgarden cover band doesn’t reflect poorly on us. People wouldn’t let their kids listen to black music, but they were totally happy when Elvis came out.

BLUSH: How have things in Seattle changed since grunge went international?

THAYIL: The benefits aren’t as obvious as the detriments. In the last year, being home, I’ve been more paranoid when dealing with public situations.

BLUSH: Despite your use of soaring, high-register vocals and hard, nasty guitar, you’re not what most people would consider a typical heavy-metal band. What’s your relationship to metal?

THAYIL: None of us had much respect for it or listened to it prior to the time we got together; that’s the truth. A lot of people began to think of us as a metal band, and maybe we’re really a good metal band because we never used the metal scene as a source of inspiration. It wasn’t until after we had been a band for a few years that we started referring to stuff other than punk rock and art.

BLUSH: You’ve toured with many big arena bands like Metallica and Guns N’ Roses. Have any of those experiences taught you what you don’t want to be?

CORNELL: We learned that it isn’t necessary to be what those situations create. It isn’t necessary to be an untouchable rock-icon guy surrounded by bodyguards and be ushered in and out and have everyone do everything for you. It isn’t necessary to change the way you present your band to the public just because you’re successful. That happened a lot in the ’80s: there was a school of thought that said people would like you more if you acted like you were the unattainable star. Right now it’s turned around the other way. It’s like, “I like him because he’s the type of person I can sit and talk to,” as opposed to being attracted to a band because they’re better looking than you and have more women around them and really nice cars and motorcycles.

BLUSH: What do you see as the next wave of rock fashion?

THAYIL: There’s a neobeatnik trend going on. Short hair, thick-rim glasses. Coffee-shop intellectuals. People are going to start collecting Boys’ Life magazines and stuff—the “I smoke filter-less cigarettes and drink too much coffee” trip. The people I see adopting that trip are people who separate themselves from grunge culture in Seattle. People on Sub Pop are much too sophisticated to look like animals. If there was any point to grunge, it was functional clothing. You wear shoes that you can do work in.

BLUSH: You’ve played on many benefit records. Why did you choose these particular causes? Do you ever feel they divert you from making your own albums?

THAYIL: The fact of the matter is that we get asked all the time. But there’re these causes where people are like, “What can you do for us? You guys have success and stature; you can make money for us and at the same time present yourselves to the public as altruistic and civic-minded.” So it’s an exchange. I don’t mind looking altruistic and civic-minded if we’re actually being that way.

BLUSH: Chris, how does it work being married to your manager [Susan Silver]? Is it ever like Spinal Tap?

CORNELL: Not really. It’s more of a push-and-pull thing. Sometimes she’ll do something the band doesn’t agree with, and I’ll get defensive of her; and then the band will do something she doesn’t like, and I’ll get defensive of the band. It’s not just my problem; everybody has to try to be sensitive to the fact that that’s the situation. It’s got to be hard for everyone at some point or another. I’m proud that it works as well as it does. Her being engrossed in the music business as her job and my trying to avoid it are the biggest obstacles to having a normal relationship.

BLUSH: Did you cut your hair because you were worried about becoming a parody of yourself?

CORNELL: I don’t care what people think of me or for what reason they think of me. I don’t feel like I don’t know who I am to the degree that I have to change my hair to create a new me. But to answer your question, I still think I’ll get a lot of chicks, but they will be divorcees, as opposed to riot grrrl chicks.

BLUSH: What do you do when you’re not being rock stars?

THAYIL: Being a rock star is really a 24-hour-a-day job, and you really can’t escape it.

BLUSH: How would you like to be remembered?

THAYIL: In 20 years I’d like to see young musicians discovering our records and being influenced by them, just like people were yelling about the Stooges five years ago. I just wouldn’t want to be a blurb.

THIS INTERVIEW ORIGINALLY APPEARED IN THE MARCH 1994 ISSUE OF INTERVIEW.

For more from our archives, click here.