Raury’s Revolution

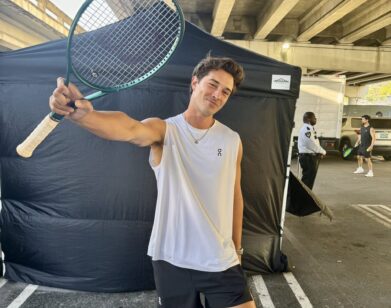

RAURY IN NEW YORK, OCTOBER 2015. PHOTOS: RAF STAHELIN/LALALAND ARTISTS. STYLING: MARINA MUNOZ/LALALAND ARTISTS. GROOMING: LISA-RAQUEL USING REN AT SEE MANAGEMENT.

Within one song, rapper, singer, songwriter, and producer Raury can seamlessly transition from a folk-tinged ballad, to spoken word, electronic sonic effects, and vocal distortions. On his debut album All We Need (Columbia Records), the transition comes full circle, with each of the 14 tracks displaying his wide-ranging talent. At only 19 years old, the Stone Mountain, Georgia native (about 20 miles outside of Atlanta) seems to know exactly who he is, where he stands, and where he is going.

All We Need features collaborations with the likes of RZA, Tom Morello of Rage Against the Machine, and Big K.R.I.T., among others. The songs have titles as visionary as “Revolution,” with lyrics like “Lord save this burning earth…Talkin’ ’bout a revolution…I got some news for you, man / Your so-called constitution / Will advocate the mass pollution / To keep us from the evolution / From the evolution, the revolution,” but also relate to everyday experiences. On “CPU,” for example, he sings about cheating and a relationship going sour: “Stop doin’ shit to get in my head / But I want you / So I don’t even get upset … You said I can’t love you right / But two wrongs don’t make it right.”

Raury blends the world of music with activism. Earlier this year, he made an appearance on The Late Show with Stephen Colbert, wearing an anti-Trump jersey following the host’s interview with the presidential candidate. When we meet him in Manhattan, he’s just returned from recording a segment for CNN in which he discusses politics, Black Lives Matter, and more. When performing a sold out show at Bowery Ballroom the following night, he is unafraid to speak his mind and commands the audience’s attention through sharing personal anecdotes, followed by requests for everyone to start jumping or shine lights in somber moments—all of which are obeyed without hesitation.

Raury’s eclectic mixture of music and poetry stems from his openness to life experiences as well as his range of influences, which includes everyone from Kanye West and Kid Cudi to Andre 3000, Bon Iver, Fleet Foxes, and Marvin Gaye. Prior to upcoming tours with A$AP Rocky in Australia and Macklemore in Europe, we caught up with Raury during his North American headlining tour, The Crystal Express.

EMILY MCDERMOTT: Thanks for taking the time to speak with us and do the shoot.

RAURY: It’s not a problem. I like press. It keeps me in the loop. With so much going on, if I didn’t do an interview, I’d probably forget about it because so much is happening. You’ll probably ask me about something I’ve forgotten about and I’ll be like, “Oh, that did happen.”

MCDERMOTT: That’s a nice way to think about it. Your album came out a few weeks ago, how does it feel to have it out?

RAURY: It’s completely changed my life. My life is at a completely different point, especially with all the things that came with preparing for this tour—the feature opportunities that come from new people because I’m on their radar, the newfound respect that a lot of people have for me. I can feel it. It lets me know that all that work that went into it was not in vain. I can only imagine what it will do when it’s been out for two or three months.

MCDERMOTT: What do you mean “newfound respect”? What has changed?

RAURY: When I dropped Indigo Child, I was seen as a force to know, like, “Watch this kid, this is something special,” but at the same time, people, especially some peers, were like, “This kid is a wildcard, let’s see what he’s really about.” Some people had a perception of what they think I’m about, who I’m going to become, or the path I’m going to take, but this album shows you clearly what direction I’m going in. The people waiting in the back to see what Raury truly is, now they know.

MCDERMOTT: That’s how I feel right now, you’ve been on my radar but I was like, “What’s coming come next?” Listening to the album, I was amazed at how cohesive it is with so many seemingly disparate sounds. How did you select your collaborators?

RAURY: Like I said about Indigo Child, a lot of people were waiting to see what happens, so it came down to who was truly passionate about me, who truly understood me, and who truly wanted to be a part of what I’m becoming. So Jack Knife, RZA, Tom Morello, Danger Mouse, Malay—these are all people that believed in me from the jump, people who just genuinely wanted to work with me and didn’t just want to work with me for a paycheck or because of some external reason. So that’s how I selected my collaborators: based on how strongly they felt about me. Malay already has his Grammy; these people have already done things, so it came down to their personal mission. Do they want to help me shake the world up? And Danger Mouse, he’s also from Stone Mountain, from the same hometown as me.

MCDERMOTT: So have you known each other from a long time?

RAURY: No, only since we started working [together], which has probably been a year now. It was that connection. When I wanted to get Tom Morello on “Friends,” I saw so much resemblance with what was going on with him in Rage Against the Machine in the ’90s—coming right off of the cusp of rock ‘n’ roll in the ’80s, it was rather dark, it was sex, drugs, and rock ‘n’ roll. Rage Against the Machine came about in the ’90s and they were like, “Forget all that, we’re about raging against the machines, we’re about revolution, we’re about this message.” I felt like that’s a similar thing to what’s going with me in hip-hop. History repeats itself. Also, Tommy got the solo back to me the next day. I’m not saying you need send back a feature tomorrow, but if someone’s not truly excited to work or be a part of it, I don’t want to be forcing them or paying them. A lot of features come from a genuine want to contribute.

MCDERMOTT: I know some artists, when they do collaborations it can take six months or more to put a song together. One day is such a quick turnaround. What is the writing process like for you? Were all of these songs written in the past year?

RAURY: “Friends” was written around the same time as “God’s Whisper.” I produced it and put it in my back pocket for the album. The whole song writing process starts with the inspiration. You’ve got to live life and experience things in order to have things to write about. You can’t just hole up in the studio and be there for six months. Most of these songs come from experiences that have happened to me, real life conversations or moments that snowball into songs.

It usually starts off with me and a guitar. I have the chords, then I go into the studio with Jack Knife and play him the chords, and then we record that and continue to build it out together. I go in with Jack Knife, or Malay, or Danger Mouse, and these people help me tap deeper into this well of creativity and get closer to mastering it. They act as sensei’s because I already produce, so why am I working with another producer? Because this producer knows so much more. I’ve learned so much from all of them.

MCDERMOTT: They open up other doors.

RAURY: Yeah, doors that I really would have never known existed if it wasn’t for them. I wouldn’t even say collaboration was my strong suit starting out. I was probably pissing people off in the studio. We won’t go there, but working with them has helped me see and actualize that it’s a necessity to collaborate. We’re here to give each other ideas and to learn from each other and to grow. That’s how we get the best things, through collaboration and working with other people.

MCDERMOTT: What is one of the biggest things you’ve learned from working with other producers?

RAURY: Less is more. It doesn’t even necessarily apply to songs [or] music, it just applies to life. Less is more. For example, if I stack a song out with music and everything sounds amazing, the listener might not get to experience the [lyrics of the] song. If I go out on stage and I’m flailing and dancing and yelling the whole time, it’s high energy and the audience feeds off of the song, but what about that aspect of less-ness or minimalism or composure? I learned that less was more when performing “Devil’s Whisper” on Colbert, with the Donald Trump host situation. I could have gone out there screaming, “Fuck Trump!” and “Forget this!” and “I hate people that think like this!” That’s a lot, but less is more—just go out there with a shirt that is your protest. That [shit] became even more notable and bigger. So less is more. It applies to music, it applies to talking to a girl you like, it applies to life, food, all kinds of things. Less is more.

MCDERMOTT: There are a lot religious allegories that resonate throughout your lyricism. Where does that come from?

RAURY: I was raised Baptist Christian. The whole southern genuineness and happiness about people and interacting with people, it’s always been instilled in me. I’ve always been a very happy person, very good, really friendly. The aspect of spirituality, I learned from the internet, from conversations with people, and from some of my favorite artists, from Lennon to Martin Luther King. For the most part, I feel like everybody is talking about the same thing.

Somewhere along the lines of history, the truth was lost between man’s hunger for power and man’s hunger to control people with religious dogmas. So I feel like there’s a common ground we can all find one day and we’re just scratching upon the surface of it. I believe that everybody is a spirit inside of a body with a purpose, and I believe that everybody is connected in a way beyond what they can see, connected beyond what they can truly understand. I believe when you go to sleep and have a dream, it’s not just a chemical reaction. I believe when something’s familiar to you, that means something. I don’t believe in coincidence; everything happens for a reason.

MCDERMOTT: Do you dream a lot?

RAURY: I’ve been having some dreams lately that I can’t wake up and explain to anybody because it’s crazy, or I just vaguely remember. But one thing I do remember is how real it was and how elaborate it was, to the point where I wake up and feel like I’m leaving behind a completely relevant life. This has been happening too consistently. Like, “Yo this can’t be just dreams!” I feel like there’s some important people on the other side.

MCDERMOTT: For only being 19, you seem to really understand who you are and where you stand in the world. How have you become so confident in what you believe? That’s an extremely hard thing for people at any age to do.

RAURY: I was a part of a program called C5 Youth Foundation, a leadership program where I went through a lot of outdoor camping experiences. The way they select people [is that] you get nominated by your school because they see some kind of potential in you. My particular situation is that I took up for a lot of kids that got bullied. If I got into a fight at school, it was because I told somebody to shut the fuck up because they were trying to get their laugh for the day off of somebody else. I was the only one in my county nominated for [the program]. I made it in and for a month every summer, overnight, I was gone in that program. Your counselors were probably the most opinionated, hardcore, activist-like college kids, so they were my mentors growing up. They showed me all kinds of views, deeper into more spiritual things, they showed me the effects of hyper-capitalism and all kinds of things that were going on in the world, and I formed an opinion.

Also, I realized leadership doesn’t come down to knowing the right answer or being right all the time; it comes down to being decisive. If I didn’t decide when I was 14 that music is what I’m going to do, I’m going to go on the internet, I’m going to read shit, I’m going to learn how to play guitar even better—if I didn’t make that decision, I wouldn’t be here at 19. I’d still be fumbling between music, or being a music teacher, being a masseuse, being a camp counselor, ’cause I liked camp. It all comes down to making a choice. That’s what the scary thing is. Now I’m completely missing out on going to college and studying politics.

MCDERMOTT: You say missing out, but you’re experiencing this kind of insane other—

RAURY: I don’t know, I could be missing out. I could be missing out on a really human experience that most people go through. I’m jealous of my friends and peers who have to experience some of the struggle because that’s when life is most real, when you’re most passionate and hungry for things. Once you get to a place of comfortability, you have to fight to feel that way. It’s an active process. My manager still holds on to a shitty car to remind him that this is still a grind. But as far as knowing who I am, it just came down to that decisiveness. I nurtured that decisiveness and it shows through in everything.

MCDERMOTT: Do you have any role models who helped you learn how to be that decisive, aside from camp counselors?

RAURY: I don’t know if I learned decisiveness specifically from looking at somebody. It’s from trial and error, from me realizing that the more I was decisive about something, the more likely it was to turn out well. It’s that law of attraction thing; it’s so real and it’s how I got here. When you truly believe in it, you know it’s going to work, and if it doesn’t, then just keep practicing. More often than not it’s going to work out when you’re decisive and in your mind you see yourself becoming successful. But you have to make the decision.

MCDERMOTT: Going back to childhood, I know you wrote your first song, “Oh, Little Fishy,” when you were three years old. How do you even remember something from that age?

RAURY: “Oh, Little Fishy” was a song I made when I was three and was at a very impressionable age. I don’t know how I remember it, but I do. I like to share that story but when I do, I think the reader thinks, “Oh, he was born to do this,” but I also had my head shaved all the time because I loved Michael Jordan. I was just born dreaming and looking at stuff, like any other kid. So “Oh, Little Fishy,” I think was because I knew of Michael Jackson and I was so impressionable; I tried to dance like him and I tried to sing songs like him.

MCDERMOTT: And you taught yourself guitar from YouTube, right?

RAURY: Mhmm. When I was 11, I finally got a guitar after two years of begging my mom, a little crappy $20 guitar from Wal-Mart. We didn’t have too much monetarily, so she looked out for that and I was so happy about it I never put it down. My whole first year, I was just strumming. It wasn’t tuned, I didn’t know anything about a guitar, I never pressed down on a fret; I was just plucking it string by string thinking I was playing a song.

MCDERMOTT: So when did you start teaching yourself and actually writing songs with it?

RAURY: I didn’t really get into songwriting until I was 14. I had raps and all that, but who didn’t write poems? Nobody took that seriously. When I was 14 I started writing songs about extremely dark and depressing shit because I was really depressed at that point. That’s what got me songwriting, being in that dark place and not knowing what else to do but write about it.

The first thing that I made that I was proud of was the first thing that I put up on SoundCloud: “Bloom.” I was 14, I didn’t like to sing, I didn’t think singing was cool, I was embarrassed about that, but I put that song out there and was like, “Maybe I should keep at this, maybe I should keep at being a vocalist along with a lyricist.” At first I was planning on just being a straight rapper of truth. I loved Lupe, Wiz, Cudi, Pac—I wanted to be like that, but there was more to me.

MCDERMOTT: You draw inspiration from so many different musicians and rappers. We don’t have to go into the full history, but who have you been listening to recently?

RAURY: Recently all I’ve been listening to is a lot of old T-Pain. A rapper-turned-singer, T-Pain is so responsible for everything. I realized that what a lot of kids who are eight years old right now are going through with Fetty Wap is what I went through with T-Pain, and it’s so beautiful. T-Pain was the best. I’ve been listening to T-Pain religiously.

MCDERMOTT: Why his earlier music?

RAURY: The honesty and relate-ability. It wasn’t cool to be in love with a stripper. That’s not something you would say and it would be cool, but he said it. What works with a song—especially when you say something that everybody is thinking and ashamed to say—is that they can live it out through that song. “Hotline Bling,” nobody wants to admit they’re jealous about a girl who has moved on and is doing different shit. No one wants to admit they’re in love with a stripper. [laughs] It all goes to say, I learned honesty. When I wrote “Devil’s Whisper,” I didn’t want to talk about how I have a side of my mind that thinks about making music for profit instead of for the people, but I do, and that’s the reality. So with T-Pain I’m learning a lot about transparency, and that’s from a lot of other artists, too. That’s what the best art is: transparent, soul-bearing, embarrassing to the artist. Just being open.

MCDERMOTT: Which you are through social media. You have such strong online presence.

RAURY: It has a great deal to do with my age. I’m one of those kids of the passback generation, the age of the internet.

MCDERMOTT: Per your Twitter handle, you must really love coconut oil.

RAURY: Oh yeah, coconut oil papi all day! I’m wearing it now. You can use it to brush your teeth, you can use it to help stomach aches, you can use it as lotion, you can use it in your hair, you can use it as a massage lotion type of thing—that’s where coconut oil papi comes in. [both laugh] You can use it as a nice little masseuse topic, so coconut oil papi.

MCDERMOTT: Looking back at the creation of this album, what is one moment that you always will remember?

RAURY: [pauses] I almost freaked out in the middle of making this album. I almost lost it and completely scraped it and started all over. In the process of making, sometimes I’m writing a song and think, “Who’s going to listen to this?” I compare it to other songs, apply it to certain situations, and think about where it will fit in. It got to a point where I wanted to make an album that would fit it because I never know what I’m going to make next.

Malay and Justice [from my management team] brought me back down like, “Yo what you have is exactly what needs to happen. What you’re making right here, it’s exactly what people need.” That’s advice I’ve given to someone and I’ve given myself. Something that you feel that way about is exactly what people need to hear—that’s that freshness, that newness that’s going to break boundaries.

I realize that I’m not doing this for the profit—I would love to, and at some point I believe that I will build up to a point where I can sell millions—but this is to plant seeds and to push culture into opening doors for artists that want to make music and have that same message that I have. There’s a lot of people out there right now who are losing the message and making things to fit in, making things for profit, which is fine, but people need to know that you can make music like this and find success. So that was a weird pivotal moment, and that was around the end of [making] the album.

MCDERMOTT: I hear your live performance, this tour your starting, is going to be quite the show. How do you adapt recorded music for the stage?

RAURY: Yeah, the Crystal Express, we’re on tour right now and we’re giving the best shows. It’s deeper than just going and hearing music. It’s a conversational show, where I open up and talk about personal things, what the song is about and what it’s for. We make sure that no matter who you are, if you come by yourself, if you come with a crew, you never leave feeling alone because you realize that you’re surrounded by people with the same mind state and the same views as you. It’s deeper than a bunch of people going there to get drunk. You can come there and get drunk, of course, but the live show is 50 times more amazing than the runs we’ve done on Indigo Child. We’re just now starting and it’s only going to get better.

ALL WE NEED IS OUT NOW VIA COLUMBIA RECORDS. FOR MORE ON RAURY, VISIT HIS FACEBOOK.