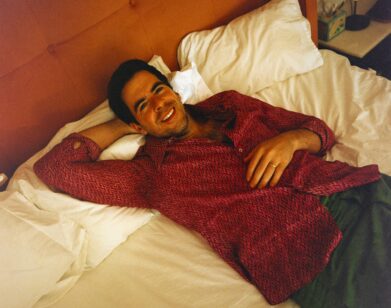

25 Years After Paid in Full, Rakim is Still Reaping Dividends

RAKIM

The prevailing ideas about Rakim frame him as the classic street-smart MC, a man whose tricksy wordplay and artistic ideals are too potent for the mainstream. This does the musician a disservice: he’s more versatile than that. Remind yourself, for example, of Rakim’s comfortable cameo in the video for Truth Hurts’s R&B chart success, “Addictive.” There he is, quoting his own work over a few bars, with liquor poured for him on cue, looking every inch the genre-crossing early-noughties rap star. As Nas details in his homage to Rakim, “U.B.R. (Unauthorized Biography of Rakim),” his subject’s initial solo project, The 18th Letter, was the first million-dollar deal in rap. The size of the paycheck was a consequence of public desperation to hear Ra return to the mic, after years of legal wrangling with his former music partner Eric B. Rakim wanted to go solo, Eric B. tried to stop him: the DJ refused to sign their label’s release contract, stalling Rakim’s creative freedom in the process.

Paid in Full not only proved a commercial success; it pioneered a new form of hip-hop. Rakim dissolved the prevailing rules of hip-hop rhyme structure. Gone were the bouncy, neatly-metric bars that characterized the flows of MCs like Kurtis Blow, replaced with something more in the line of poetic free verse—the casual, speech-driven hip-hop that predominates today.

In advance of a SummerStage performance this Sunday celebrating Paid in Full‘s 25th anniversary, Rakim caught up with Interview to discuss success, the qualities that make a great MC, and his and Eric B’s iconic debut album.

NICHOLAS MALTBY: What’s on your mind at the moment? What’s inspiring you and interesting you musically?

RAKIM: I think just hip-hop in general, with all the crazy flak that hip-hop is getting. I still try to find the part of it that inspires me to keep doin’ what I’m doin.” I love listening to old records to keep that nostalgic feeling; it allows me to not lose the love for this hip-hop.

MALTBY: What records? Are you talking specifically hip-hop, or broader than that?

RAKIM: Broader than that. The classic R&B records of the ’70s and ’60s. I got a lot of vinyl, a lot of music in general in the house. I go downstairs, heap the turntables up, play something that will get me in the mood; if I don’t sample it, it’ll just take me where I need to be.

MALTBY: I want to talk about SummerStage and Paid in Full. Is it something you’re tired of answering questions about?

RAKIM: You know, Paid in Full is a classic album, man. It kind of got me to where I am now, so I can never get tired of Paid in Full.

MALTBY: How do you see the balance between you and Eric B on that album?

RAKIM: Eric was more the businessman of the group. Back then I was young: all I cared was about was writing rhymes. And he kind of gave it that look at it where, he was like, “Yo, this is gonna be big—let’s make sure that we shoot for the stars.”

MALTBY: You grew up in Wyandanch in Long Island, outside of the traditional New York hip-hop environment. Is that something that made you more of an original MC?

RAKIM: I think growing up where I came up gave me an advantage and a disadvantage. The disadvantage was I wasn’t living in the five boroughs—I was on the outside looking in. But in a good way. I kind of came up with a little more imagination towards the game. Hip-hop was just this big movement that I wanted to be in, but I had to reach a certain level. So it kind of of gave me the extra push to want to be down.

MALTBY: You’ve criticized your delivery in Paid in Full for being too passive—you were reading the lyrics during the recording. Do you not like your flow as much on that album as on your later material?

RAKIM: Well, I think it was being new—not being in the studio enough to know what the best way to lay down my material was. I used to sit down and Eric would come up with a beat, and I would write right there in the studio, and as soon as I was done I would go in and read it. My thing was I would rather know it by heart: I wish I can go back, because I feel when I know my work by heart then I lay it down it better.

MALTBY: People say when you’re studying poetry you should learn it.

RAKIM: Right, ’cause you can feel it and you can you can make the listener believe it more. But for whatever reason, that album was one of the best hip-hop albums ever made—so if it wasn’t broke, why try to fix it?

MALTBY: You’ve talked of your use of persona. It’s something you’ve kind of developed over time. Is that a conscious development—using narratives from different perspectives?

RAKIM: No doubt. I always wanted to kind of make the listener feel like it was them that I was talking about, or to the point that I could say the rhyme, and feel like it’s them saying it.

MALTBY: Nowadays, hip-hop is so much about branding and lifestyle, and perhaps that’s why people are talking much more in the first person and not as concerned about the listener.

RAKIM: You’re definitely right on that. I mean now, everyone is kind of telling their story. Back in the day, music imitated life. Now it’s the opposite way around: life is imitating music. It’s like whatever the rappers say, people think that that’s how we’re supposed to be; but back then, we kind of looked at the streets, and we made music for that.

MALTBY: “What’s On Your Mind” is a song that you wouldn’t really find MCs making now, because it begins on the subway.

RAKIM: Too many rappers don’t want to say that they take the subway no more, or a cab! But we don’t get a lot of that natural or regular lifestyle no more, which the listeners go through every day.

MALTBY: Could you talk about 4th & B’Way Records—how that was? And how were Rush Artist Management and Russell Simmons?

RAKIM: We started off with Zakia Records, which was a small independent label. Once the album started doing good, what Robert Hill tried to do was give us a little more push, and he did the deal with 4th & B’Way—a major label. They did as much for us as I felt a major should. Def Jam was my management. It’s funny, because my brother Ronnie Griffin used to go on tour with Kurtis Blow, and Rush was the manager. It was one of them things where my brother knew Russell and he took me to see Russell. Of course Russell made me see the bigger picture. His idea of a successful hip-hop artist really gave me a lot of incentives and put me on track to realize what I had to do to be successful. I just learned how to take the best from all my situations and use it as fuel.

MALTBY: What do you want and expect from a DJ?

RAKIM: He’s got to have that complete package. If it’s just a DJ who plays music for the public, I think he has to know not only how to mix good and how to DJ good, he has to know the history, so he will know what to play and know the significance of what he’s playing. I notice the difference right away when a DJ knows how to command a crowd.

MALTBY: On that note, are you looking forward to Funkmaster Flex at Summerstage?

RAKIM: Oh, no doubt. Flex is one of the DJs that understands the movement. I’m looking forward to see Flex put it down.

MALTBY: Do you feel that there is a noticeable difference between the reactions you get in New York and abroad?

RAKIM: I think in New York, on the streets, I get that godfather love. In New York, they kind of rode with me from day one: they understand who I am. When I go abroad, it’s the same thing, but it’s a little different. In New York, it’s like that lyricist: the cat that stayed true. When I go abroad, it’s more of a hip-hop god thing: they appreciate what I brought, and they feel that I started a lot of trends that are going on today. But performing, I get the same response just about everywhere. The crowd sings my whole show, or damn near word for word.

MALTBY: What do you think makes a lasting MC?

RAKIM: I think a rapper who’s universal, a rapper who uses a lot of reality. The truth never wears out. It’s about the listener. When it’s something that a listener can relate to, it will never play out. You know, of course, this is our livelihood, and if you in this, of course you gotta make money. But if you’re looking at it like, “I want to sell 4 million records,” it’s all right when music is fun; but when things get real you don’t want to hear certain songs, you want to hear something more suitable to the moods you in. A lot of times when people listen to music it’s because they feel down, and that’s when serious hip-hop comes into play. When times is hard, people can hear a rapper that inspires them to do what they supposed to do.

RAKIM WILL PLAY CENTRAL PARK SUMMERSTAGE WITH EMPD AND FUNKMASTER FLEX ON SUNDAY AT 3 PM. FOR MORE ON THE ARTIST, VISIT HIS MYSPACE.