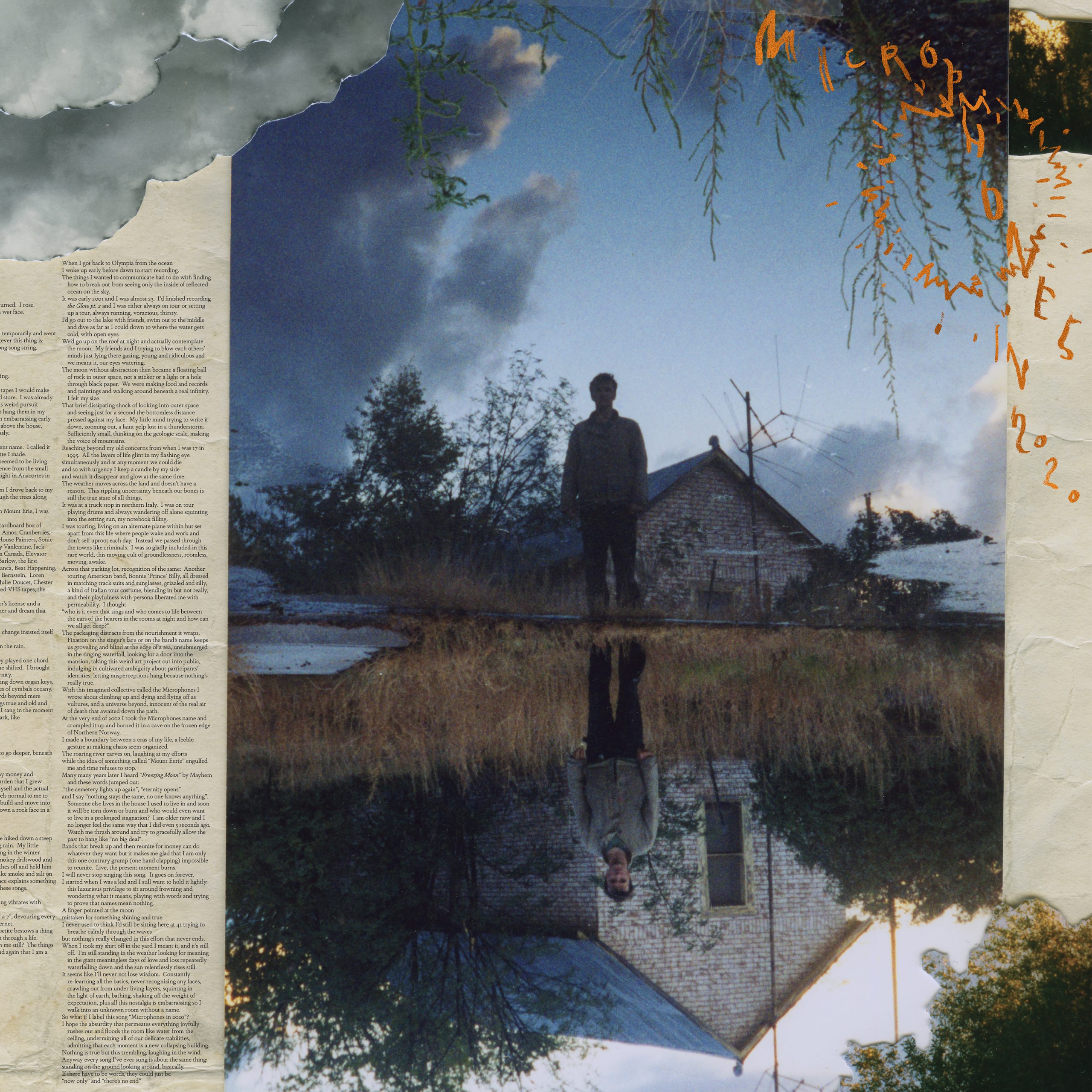

Phil Elverum in 2020

The Microphones in 2020.

If the name Phil Elverum doesn’t ring a bell to you, perhaps you know the singer-songwriter as The Microphones, the indie folk-noise band he formed in his mid-twenties. The 2001 Microphones album The Glow Pt. 2 has endured through the decades, finding its place in the indie canon alongside albums like Neutral Milk Hotel’s In the Aeroplane Over the Sea. You may also know Elverum by another name, Mount Eerie, a continuation of his music career that brought him renewed acclaim after the release of his 2017 album A Crow Looked at Me, a breathtaking and devastating account of losing his wife, the songwriter and cartoonist Geneviève Castrée, to cancer.

After 17 years, Elverum has returned to The Microphones with a new piece, simply titled The Microphones in 2020. Simultaneously a song, an album, and a supplemental lyric film that spans 45 minutes, it is an attempt by Elverum to map the genesis of his music career, and to shed these previous names that brought him recognition. The musician hopped on the phone with me in his most natural state: building a house in the middle of the woods in his home state of Washington. He spoke about the ongoing pandemic, being a single father, the beauty of Twin Peaks, and the dangers of singing about breakfast food. This is Phil Elverum in 2020.

_ _ _

CONOR WILLIAMS: Hi, Phil. Where are you? Are you back in Washington?

PHIL ELVERUM: I’m not in my house right now, but I’m near home. I’m working on a house-building project. I’m out in the woods at the moment.

WILLIAMS: In your element.

ELVERUM: [Laughs] Yeah.

WILLIAMS: Do you remember the last place that you were before you had to quarantine?

ELVERUM: I live on this island, and so it’s pretty distinct—you have to take a ferry to go off-island and it’s a big deal. Or now it feels like a big deal. So I remember the last big off-island trip. I went to a hardware store to look at some windows. It was during that phase where we were like, bumping elbows, and nobody was really wearing masks. It felt dangerous to go to a hardware store. I’m kind of an introvert; I’m fine not pursuing social interaction. I can go for a really long time. So it’s interesting at this moment to see the mobs of people who just can’t take it anymore, who just so desperately need to go out and cheers their beers with each other, and hug and swap germs. Even now in this moment, where they know this will lead to thousands and thousands of deaths. And billions of dollars of loss. “But I need this hug. It’s worth it!”

WILLIAMS: Have you found your own upside in all this?

ELVERUM: I’m so lucky and privileged to be positioned where I am. It’s a spacious, healthy place where, for the most part, people are on board with public health—the people who live here, not so much the tourists. The hardest part is the total lack of childcare. There’s no school and no childcare and I’m a single parent, so that’s pretty hardcore.

WILLIAMS: Is this a useful time for you as a dad, or is it difficult to explain this world that isn’t the world that we’re used to?

ELVERUM: That part isn’t so hard. She’s on board with it. I’m not great at any kind of homeschooling. I’ve made zero effort about that. That’s a little bit of a concern. Maybe she should know how to read by now, and we’re not really working on that.

Elverum and his daughter. Photo by Rin-San Jeff Miller.

WILLIAMS: She’ll pick it up. In college, I was dealing with a lot of intense grief, and there were two albums that came out around that time, Sufjan Stevens’s Carrie and Lowell, and your album A Crow Looked at Me. They met me perfectly. I ended up making a film about my grief and your album was really all I listened to while I was making it.

ELVERUM: Wow.

WILLIAMS: I know the circumstances of our grief are different, but I appreciate that we’re both fluent in the same language. In this new piece, there’s a phrase you use: “The beast of uninvited change.” It feels like such a specific and yet broad way to name death.

ELVERUM: There’s a universality to it. I’m glad that it was useful and that the timing matched.

WILLIAMS: When you had finished A Crow Looked at Me, did it feel like any sort of closure at the time?

ELVERUM: I remember ending that album with the two songs, “Soria Moria” and “Crow,” and those do kinda have a closure vibe. Because they’re about me and my daughter moving on with our life, and also being watched over by this crow. Not so much closure, but survival.

WILLIAMS: Did you think that you would continue to explore this? Or did you think, “Oh, I’ve made this album and now I’ll go and do something else.”

ELVERUM: No, I knew I wasn’t finished exploring it. Now Only, the songs for that album, they just kept coming out. Even after that, I thought I would have more to say on it. But my life went in a different direction.

WILLIAMS: You’ve talked about how real-life suffering was a sobering clarification for you. It seems like there was a realization made that you couldn’t speak about these things in a poetic way anymore.

ELVERUM: At first, I thought I was done with music. When Geneviève was sick, and especially after she died, it seemed like, “What use is music?” So I was surprised that these songs were coming into my head. I started recording them without any intention of releasing them. I was just doing what I usually do. Which was to distill all the mass of words in my head into something a little more poetic and musical. I was doing it out of habit, mostly. I think I realized as it was happening that it was really helpful for me, personally. That was enough of a reason to keep doing it, and that’s probably why I’ve kept doing it. I’ve kept looking at my own experience and my own existence in that way of trying to sort through it and make something useful. Find some meaning in it. I haven’t actually thought that much about the connection between A Crow Looked at Me and this new Microphones thing. I’m trying to remember what A Crow Looked at Me is like. [Laughs]

WILLIAMS: Well, you’re speaking in such a personal way, whereas all the Mount Eerie stuff is still about you, but it’s cloaked in mysterious soundscape vaguery.

ELVERUM: Right, yeah. It’s more exploring big ideas. And using the language of big ideas, rather than like, “I went to the grocery store.” I still want to talk about big ideas, I just want to use a vocabulary of the everyday. But with all of those, I’m still trying to get at some kind of meaning of life. Not the meaning of life, but you know, something deeper than the circumstances. Something that underlies the exterior circumstances.

WILLIAMS: On Now Only, you talked about watching a documentary about the Beat poets and how Jack Kerouac’s daughter sort of upended her father’s legend. It seems like with this new piece, The Microphones in 2020, you’re providing a context to work that you’ve made that has taken on a status larger than yourself.

ELVERUM: Like I’m trying to do what she did?

WILLIAMS: Yes. But to yourself.

ELVERUM: It is sort of a project of demystification. And maybe it always is. I used to play this song all the time, “Let’s Get Out of the Romance.” That’s the idea. Let’s see things clearly. I truly just wanted to look back at those years that were The Microphones accurately and honestly, and evoke what it meant or what made those times up. What made me who I was then.

WILLIAMS: The Microphones in 2020 as a piece of music feels like an answer to this motif of questions that you have in your work.

ELVERUM: I really wanted to not ask questions in it. I wanted to say “Here’s how it is. The true state of all things is a waterfall.”

WILLIAMS: You mention the band Red House Painters in the song. As a 24 year-old who is also spending most of his time listening to Mark Kozelek, I was reminded of Mark’s Sun Kil Moon album Benji. You’re both traveling back to your childhoods and talking about albums and movies that left an impression on you.

ELVERUM: I remember hearing Benji later than everyone else did, but before writing A Crow Looked at Me. That sort of realization that songwriting could take this other form informed that shift for me. Although, listening to his subsequent albums, I’ve also taken those as lessons of like, “Warning! Danger ahead!”

WILLIAMS: He’s gotten increasingly autobiographical, but his albums have become spoken word pieces about hotel breakfasts.

ELVERUM: Right.

WILLIAMS: I mean, no disrespect. You also sing about breakfast sometimes. There’s nothing wrong with that. But Benji had a poignancy to it that I think you’ve been able to retain throughout your work.

ELVERUM: Well, that’s the goal. I feel like Benji straddles that pretty well. It has that everyday hotel breakfast language, but after you listen to the whole thing, even at the end of each song, you’re left with an insight. But the subsequent albums don’t have the insight. They’re merely just the hotel breakfast. That’s what it seems to me.

WILLIAMS: Yeah. I’m not trying to start beef, but …

ELVERUM: No! I don’t want any beef.

WILLIAMS: What are you listening to these days?

ELVERUM: The past couple days I’ve been listening to black metal. Again! I always return to black metal. My daughter has been in a day camp these past few days, so when I drive around, I can listen to really loud black metal, finally. It’s so nice driving on these rural mountain roads with the windows down blasting Mayhem and stuff.

WILLIAMS: The last album that you put out, Lost Wisdom Pt. 2, is your second collaboration with Julie Doiron. What was it like working with Julie again?

ELVERUM: It’s the best. She’s so good. I don’t think of myself as a particularly great singer, but when we’re singing together, there’s something in our voices … the textures work really well together. And she’s so good at harmonizing intuitively, following along with the irregularities of my voice, that it makes me feel like a great singer. To get to write these songs that have two voices that interlock and do different things is a really fun way to get to write.

WILLIAMS: How involved is she in the writing?

ELVERUM: Not. I mean, she wrote her own melodies a lot of the time, but the words are all mine. And mostly the melodies are mine, too. There was a lot of working things out on the spot, but the songs were pretty much fully formed when she got there.

Elverum and Doiron recording “Lost Wisdom Pt. 2” Photo by Rin-San Jeff Miller.

WILLIAMS: What was the conversation like leading up to that album?

ELVERUM: We had been talking about it for years. The one we made before was in 2008 and it was just so fun. That one was also unplanned. It was an interesting discovery that our voices sounded good together. And then we toured together. I realized last year that I had this batch of songs that this would be the perfect thing for. Actually, I didn’t even have a batch of songs. I knew that I wanted to make another record with Julie. And I booked a plane ticket for her to come out here and record it.

WILLIAMS: So you just made it happen.

ELVERUM: And then I was like, “Oh fuck, she’s coming. I have to write some songs.”

WILLIAMS: That’s a way to do it.

ELVERUM: It really worked.

WILLIAMS: I know you planned to tour for this new album. That probably won’t happen.

ELVERUM: No. There’s no touring happening. But maybe someday. I do like the idea of playing a show that’s just one long song.

WILLIAMS: How does it feel to have made this thing and then not be able to immediately share it with an audience?

ELVERUM: Oh, that’s fine. [Laughs] I mean, it sucks. But, eh. It’s not that devastating for me. Most of my touring isn’t linked specifically to albums. But I hope to get back to touring someday. I love it, and I miss it. But there’s lots of other work for me to do.

WILLIAMS: Like building a house.

ELVERUM: Also, being a single parent means that touring is more complicated. It’s not as free and easy as it used to be, where I’d just go jump in a car and go sleep under a scrap of carpet in a disgusting basement. I miss that, but I can’t do that with my five-year-old.

WILLIAMS: I would hope that your accommodations have improved over the years.

ELVERUM: They have, but I have this perverse nostalgia for the suffering of how it used to be, that kind of intimacy of engagement with the people who are listening to it. Sleeping on the stage in the corner of the warehouse space.

WILLIAMS: The big headline about this new piece is that it’s the first new Microphones album in seventeen years. Which is very exciting for the music publications and for fans, but I imagine it’s not a big deal for you.

ELVERUM: I thought that maybe the headline would be that it’s one 45-minute long song. And also, in the song, I sort of undermine the significance of it being a Microphones album. I try and get at what that even means. I don’t know if that message will come across.

WILLIAMS: One of your old Microphones songs is called “Phil Elverum’s Will.” You’ve always been pretty seriously thinking about these things.

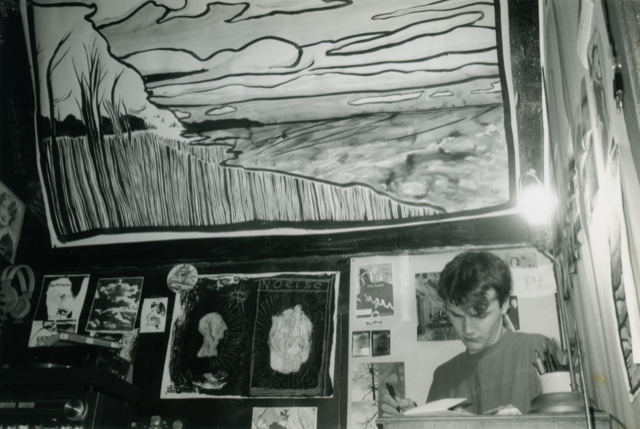

ELVERUM: The difference is that I used to explore playfully what mortality was like. I used to throw it around in poetic terms, which I think has great value. I think that’s what art is for, exploring big ideas without having to live through them. But then, when I lived through it, it just felt like, well, this is a whole different thing than writing a pretend will in the form of a song, or pretending in a concept album that I die and get eaten by vultures. That’s fine, I’m not disowning that, but it’s a different idea of what death is. I think that maybe I wanted to apply that same sort of perspective shift to my own experience beyond the death thing. And that’s maybe how I tried to look at this Microphones phase of my life. “What does this band name mean? Who was I between the ages of 17 and 23? What made that person up? What was the world like at that time? What were my values? How does that carry forward into now? Is there a difference?” At the risk of getting too heady or theoretical, how do we all, at all times, carry these multiple layers of identity through our lives as we age and transform? I think I’ve always been The Microphones, and I always will be. These superficial names get more focus than they deserve.

Elverum in 1999. Photo by Jimi Sharp.

WILLIAMS: Do you think there’s another name for yourself outside of The Microphones and Mount Eerie? Or is that just Phil?

ELVERUM: Well, I always liked this quote, “The song, not the singer.” I remember seeing it in a pull quote in a Rolling Stone interview in like, 1994 with Will Oldham. I was like, “Who’s this guy?” But those words stuck with me and have guided a lot of my thinking about music the whole time I’ve been doing it. Always trying to steer it away from the identity of the person who’s doing the thing, and shift the attention continually back to what the song is actually doing and saying, rather than who’s saying it. I think that it’s just human nature. We’re social animals who want to know the identities and the stories of who’s around us. But in my music, I’ve tried to discourage that. [Laughs] Don’t put my face on the cover of stuff.

WILLIAMS: Have you always had an interest in exploring duration like this?

ELVERUM: I’ve wanted to make a long thing for a long time. I started playing these two chords back and forth and I realized I could listen to it for an hour and not get tired of it.

WILLIAMS: There’s a lyric film that goes with it, and I was watching it again last night, thinking of it as an essay film.

ELVERUM: That’s nice of you. That’s generous to think of it that way, because it’s just a slideshow, kinda.

WILLIAMS: You’re documenting hundreds of photos that you’ve taken over the years.

ELVERUM: Yeah, I think there’s over 800. And I did actually sync them all up. I worked on it for a long time, syncing the photos up with specific lyrics.

WILLIAMS: That’s no slideshow!

ELVERUM: Thank you.

WILLIAMS: I’ll give you more credit than that. It reminded me of the Hollis Frampton film Nostalgia. He’s got a bunch of photographs and he’s burning them on a stove. And he’s describing each photograph that comes after. So the description is out of sync with the image.

ELVERUM: That sounds great.

WILLIAMS: In your photos, you appear as a ghost a lot.

ELVERUM: I had an old film camera, and it was my only way of taking self-portraits—to open the shutter, run out there, and stand there while the picture was being taken. I loved that technique.

WILLIAMS: So that was born out of an accident?

ELVERUM: Accident and necessity. I liked the ghostliness of it. I think I’ve always had a strong visual in my mind when I’ve made all this music. I know what image goes with it. I just haven’t gotten around to making the film that goes with the music. But there’s a visual component for me, definitely. And a lot of those exact photos, I’ve lived with them. They’ve been taped to the wall in all the bedrooms I’ve had. It’s been part of my life.

WILLIAMS: Were you seeking these compositions out, or were they just happenstance?

ELVERUM: Both. I remember touring, traveling always with my film camera in my backpack. There’s something about the scarcity of the material. You have to be more selective. Your visual mind is in a different place compared to a digital camera. You see things differently. I liked going through the world with that kind of eye, and being more discerning. Actually, after making that video that we’re talking about, I decided I’m going back to the film camera. I got my old camera out and there was a roll of film in there from 2007 that I finished off and sent back to the lab.

WILLIAMS: Do you think you’ll explore filmmaking more?

ELVERUM: Definitely. When I was a teenager, that was my plan for life. That was my preferred art form. For over twenty years now, I’ve been like, “When’s this music thing gonna wrap up so I can start making movies?” But it just keeps going.

WILLIAMS: What were the films or filmmakers that gave you that interest?

ELVERUM: I loved Twin Peaks. When I was in high school, I was even starting to write a script. I was going to get all my friends together, and I had chosen a small town in Oregon. .. Canyonville. We were going to go there and make this film that was very much a rip-off of Twin Peaks. I loved David Lynch when I was younger. I remember being a teenager and also watching the Colors Trilogy by Krzysztof Kieślowski. Not that I would ever know how to make anything like that, but I loved the way those three movies interlocked. The tone of them…and the clues…

WILLIAMS: Did you see the new Twin Peaks?

ELVERUM: Yes, I did. I loved it. That was special. I remember when it was first on TV, I was twelve, and I watched it with my dad. I remember the buzz about it. I was overhearing adults talking about it. Nobody at my school was talking about it. I miss that about pre-internet times.

WILLIAMS: We mentioned Kerouac, and I was reading some of his haikus last night. I’ve never been able to get into his poetry much, but I thought of you while I was reading these.

“Listen to the birds sing!

All the little birds

Will die!”

ELVERUM: Is that it?

WILLIAMS: [Laughs] That’s it.

ELVERUM: That’s so good!

WILLIAMS: Let’s see.

“I went in the woods

To meditate—

It was too cold.”

ELVERUM: [Laughs] That’s good. I love how funny they are. They’re like tweets! Little zingers!

WILLIAMS: I figured I’d leave you with that.

ELVERUM: Thank you.