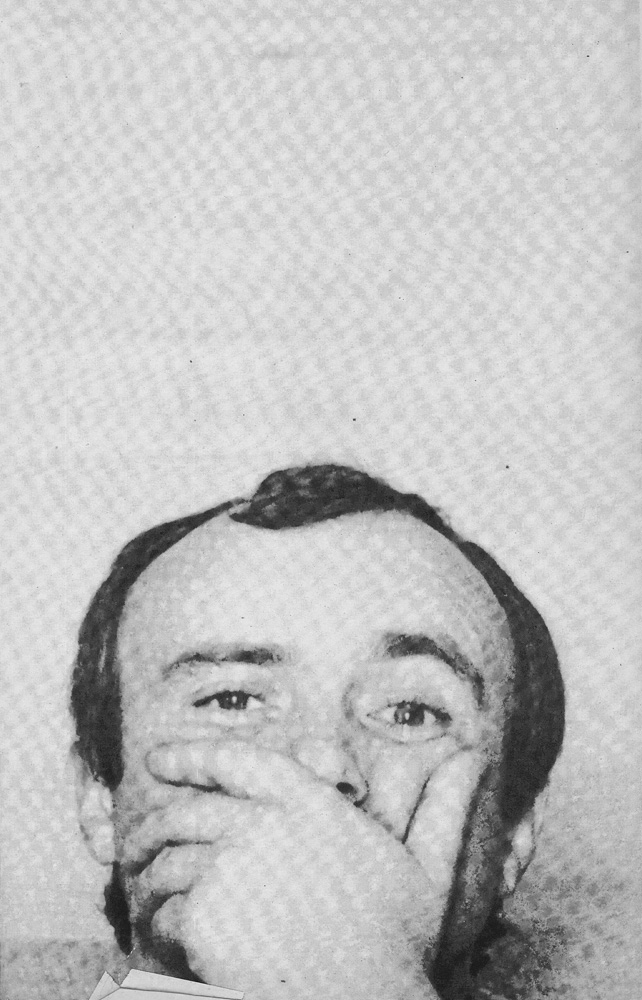

Phil Collins

Phil Collins began his musical career as the drummer of Genesis, one of the most intelligent, influential, and successful English rock bands of the ’70s, a group that’s still going strong. When the star of Genesis, Peter Gabriel, struck out on his own in 1975, Collins surprised everyone but himself by taking over as front man, lead singer, co-producer and principal songwriter of the band. Although Gabriel is a remarkable performer, Genesis continued to thrive because Collins turned out to be a remarkable performer, too—with no inclination toward doing what Gabriel did, but plenty of his own inclinations.

Becoming a star didn’t mean the end of Collins’ drumming career. He continued to drum for Genesis on record and in parts of their performances, and his drumming talents were sought by hordes of acts and acquired by a few of them, such as Brian Eno, who made considerable use of Collins on several albums, and Robert Plant, who used him for his debut solo LP. Collins was also a founding member of the fusion band, Brand X, with which he recorded and performed extensively while also working full time with Genesis.

In 1981, Phil Collins went solo—without leaving Genesis—and his album Face Value went gold, with the two hit singles “I Missed Again” and “In the Air Tonight.” In addition to producing himself and co producing Genesis, Collins has produced recent albums by John Marlyn, Glorious Fool (Duke/Atlantic Records) and Frida of ABBA, Something’s Going On (Atlantic). Frida’s album, released in the fall of ’82, has been a smash hit throughout the world, as it should be. Then late in ’82 Collins released a second solo album, Hello, I Must Be Going! (Atlantic) and embarked on a tour to bring it to the attention of the world, backed by a combo known as the Fabulous Jacuzzis.

Glenn O’Brien spoke with Collins the. afternoon before his New York solo debut at the Ritz. O’Brien found the ex-child actor still something of a child and something of an actor, and a thoroughly charming, casually witty and naturally hep human being.

PHIL COLLINS: I’m really tired. I have a midnight show tonight. I’d be ready for that in a couple of weeks but

GLENN O’BRIEN: You just flew in today?

COLLINS: Day before yesterday. I’m not too bad….

O’BRIEN: Don’t they have the Concorde between here and London?

COLLINS: Yeah, they do, but we came into Toronto. We played there last night. The trouble is that being so good on the road, when I’m off the road I do terrible things to myself. So I’m recovering from all that. But I’m fine. Don’t worry about me.

O’BRIEN: If that’s the case, do you spend enough time on the road to keep yourself out of trouble and in good condition?

COLLINS: Sure, I get really fit. Look at me.

O’BRIEN: You look okay. Of course, I’ve never seen you before.

COLLINS: Actually, I do get very fit with Genesis because I do a lot of running around, a lot of playing. So I go out on the road flabby and I come back like Schwarzenegger.

O’BRIEN: You lose weight?

COLLINS: Yeah, although the older you get the less weight you lose. I sweat off a lot. But then I like to drink so I put it back on.

O’BRIEN: I’ve never seen you play live. Do you get out from behind the drums?

COLLINS: With the band I tend to sing from out front. Chester Thompson plays drums when I’m singing. He used to play with Frank Zappa and Weather Report. When there’s no singing I go back and play on my own kit. We play together quite a lot. Sometimes when I come back to the drums he’ll stop and go to percussion. Sometimes if there’s a vocal line or two in the middle of an instrumental part I will sing from the drums. On my own tour I play keyboards as well as sing and I play some drums. I get around.

O’BRIEN: Is it hard to sing while you play drums?

COLLINS: Not for me. I did it while I was in a school group. I had a group when I was fourteen—we did a lot of Motown stuff, a lot of Styx stuff. I was the only singer in the group so I learned to co-ordinate and sing at the same time so now it’s no problein.

O’BRIEN: It always amazes me when drummers sing because it seems that every limb is doing something different…

COLLINS: It has to be second nature. It just looks so dull—to have the lead singer of a group on the drums is visually the kiss of death.

O’BRIEN: Well, did you ever think of having a. revolving drum platform on wheels that would roll up to the front when it was time to sing, maybe, with a built-in light show?

COLLINS: Fortunately, I never came up with that idea. You have to get out there and communicate—they have to see you singing. They can’t see you singing in these big places, if you’re hidden behind eight torn toms and fifteen cymbals, so I opted for the other way out.

O’BRIEN: Do you use drum machines?

COLLINS: I do use them a lot. The basis of everything I write is drum machine rhythm. I have four or five drum machines at home. I just set up a pattern, get a sound on my Prophet or piano and just sod about until I get something I like. I’m not a drummer who believes they are a threat. When I first started doing my records at home I found myself playing drums and singing along and then putting the keyboards on later. It was hard work doing it like that. It’s easier to get the drum machine going and play the keyboards, then later replace the machine with drums. But I like drum machines a lot. I think they’re much maligned instruments.

O’BRIEN: Someone was telling me about a new Linn machine that’ s supposed to be really advanced.

COLLINS: The most significant development is in the chips. The length of time that you’ve been able to get on a microchip up till now has been about half a second, which means that you have a very clipped sound, you can’t have cymbals which have a long decay. Now you can get about a second, so you can have cymbals. The new Linn has that. I have an English equivalent of a Linn which has got my own sounds in it: the “In the Air” sound for instance, and the “Intruder” sound. Well, I will have that, when they bloody deliver it, on my own drum machine. I’ve got me on chip, which is a nice thing to have.

O’BRIEN: It will, actually be the sound of you playing on the chip.

COLLINS: Yeah, when I was doing Frida’s album I spent a few hours with Hugh Padgett recording sounds that I like so I could give a tape to the drum machine company.

O’BRIEN: Can other people buy that chip with you playing on it?

COLLINS: No.

O’BRIEN: Well, if you buy a standard chip who is playing on it?

COLLINS: I don’t know. It’s this faceless character. It has gotten to the stage now that when you book people… people like Harvey Mason—a big session drummer in England—you’ll book him for a session and he’ll come to the session with the Linn drum and he’ll just program the thing with his sounds on it. He might not actually play drums, but it’s him on the Linn. When you buy a Linn machine someone has actually played on those chips in the first place, but that could be anybody Eddie Session.

O’BRIEN: Were drums the first instrument you played?

COLLINS: Yes. I was given a drum when I was about three or four. When I was five my uncle made me a drum kit that fit into a suitcase, made out of tambourines, triangles, cymbals, toy drums.

O’BRIEN: Did you ask for drums?

COLLINS: No, I think every kid… you were never given a drum when you were three years old?

O’BRIEN: No, I think that’s the last thing my parents would have given me.

COLLINS: The old cliché is, “Well, at least it will keep him quiet.”

O’BRIEN: What kind of music were you interested in?

COLLINS: My brother was eight or nine years older and he was always listening to Radio Luxembourg which played Bill Haley, Eddie Cochran, stuff like that, which didn’t interest me at all. I never ever liked that music, but when I started playing seriously, the English beat thing was just happening, the Shadows and bands like that. It was the very early ’60s. I remember buying Please Please Me. I used to put the record player on very loud and set up my drums so I was facing the mirror, that way you don’t look at what you’re doing. Then when I was fourteen I went to a teacher to learn to read drum music. I figured when this rock-and-roll thing finished I would have to make a living playing in a dance band or in an orchestra pit. So I learned to read drum music, but I found that my capacity for reading was not anywhere near as good as actually playing by instinct. I would have this chart in front of me and my teacher would have me play it and I’d play it very haltingly. I’d get exasperated and I’d ask him to play it and he’d play it and I’d say, “Oh you mean that!” and I would repeat it perfectly. Give it to me written down and I had no idea. So I decided to abandon that area of learning and ever since I’ve lived off my wits musically. When I would do sessions, if they would hum me the song I could play it, but if they wanted me to read a part, they had the wrong bloke. Fortunately, I don’t think I’ll ever have to do that for a living.

O’BRIEN: It seems to me that most great drummers started out being inspired by jazz.

COLLINS: I think so. That’s because of the freedom in jazz to develop a certain personality. People always tend to think that I’m more of a jazz fan than I really am. In great jazz there’s basically a tempo and you can express yourself around it. But now you can express yourself that way in other types of music.

O’BRIEN: You must have become a jazz fan at some point, right?

COLLINS: Yeah, I was always fascinated by big bands. I loved the very first Buddy Rich big band. I was a huge fan. I bought all of his albums. You go through fads of drumming and I no longer idolize Buddy Rich; I do admire him. I respect what he is and what he’s done and how he still kicks it around when he’s 60. What he was doing with big bands has been copied by lots of different groups, the band Yes being one of them. That style of arranging crept into rock-and-roll.

O’BRIEN: Later you learned to play piano and trumpet?

COLLINS: No, I don’t play trumpet. I pretend to play trumpet. The trumpet to me is what the violin is to Jack Benny.

O’BRIEN: How old were you when you joined Genesis?

COLLINS:I’ve been in it twelve years and I’m 31 now, so I must have been 19.

O’BRIEN: Was it a big group then?

COLLINS: I think they’d only been going on the road professionally for about a year before I joined up. They were together before that but they were still in school. They weren’t big. They were hard workin’, seven days a week.

O’BRIEN: I was wondering if you were joining a famous band.

COLLINS: No. I was joining a band that was known for working. I joined as Trespass came out, that was the first proper album the band made. That did well in some European countries. In Italy and Belgium it went to number one, but it wasn’t until three or four years after that we became popular in England as a result of hard work.

O’BRIEN: Can you be anonymous in England? If you walk down the street does everybody point and say…

COLLINS:There goes Johnny Lydon? It varies. I only go to the places where I know I’m going to be recognized. I live in a town called Guilford. That’s one of the places where Genesis used to work a lot: it’s a university town so there are a lot of kids who know me. It’s not as if I drive through town in the Rolls Royce I haven’t got, I just go down to the supermarket and somebody says “Hey Phil, I like the album.” Genesis has always been anonymous. We look much the same as anybody else. It’s only since I’ve had my picture on the record cover that people know what I look like. Also I change what I look like. Long hair and beard, long hair and no beard, short hair and beard; I’m constantly changing what I look like because it makes me think differently, gives me a different personality.

O’BRIEN: What do you think of the boom in rock videos?

COLLINS: I think with a lot of them it’s almost as if they’ve found a director who can use all these gadgets and they’ve let him loose. When I was going to do a video of In the Air, Virgin:Records sent me tapes of various directors, David Mallet, who is supposed to be very, very good, who did Bowie’s stuff and the Stones’ , stuff, Raymond Mulcai anyway, they sent me three or four tapes of endless videos—all this color coding and chroma-key. I like to have a very strong simple idea and exploit it. Like or not the videos I do, they’re all my ideas and at least I know I’ve got control over them. It seems to me that a lot of people just hand the song over to a director and sometimes it works and sometimes it doesn’t. But I dislike more than most.

THIS INTERVIEW ORIGINALLY APPEARED IN THE MARCH 1983 ISSUE OF INTERVIEW.

For more from our archives, click here.