PUNK

“Oh God, the Mess!”: Peter Wolf and Danny Fields Take a Walk on the Wild Side

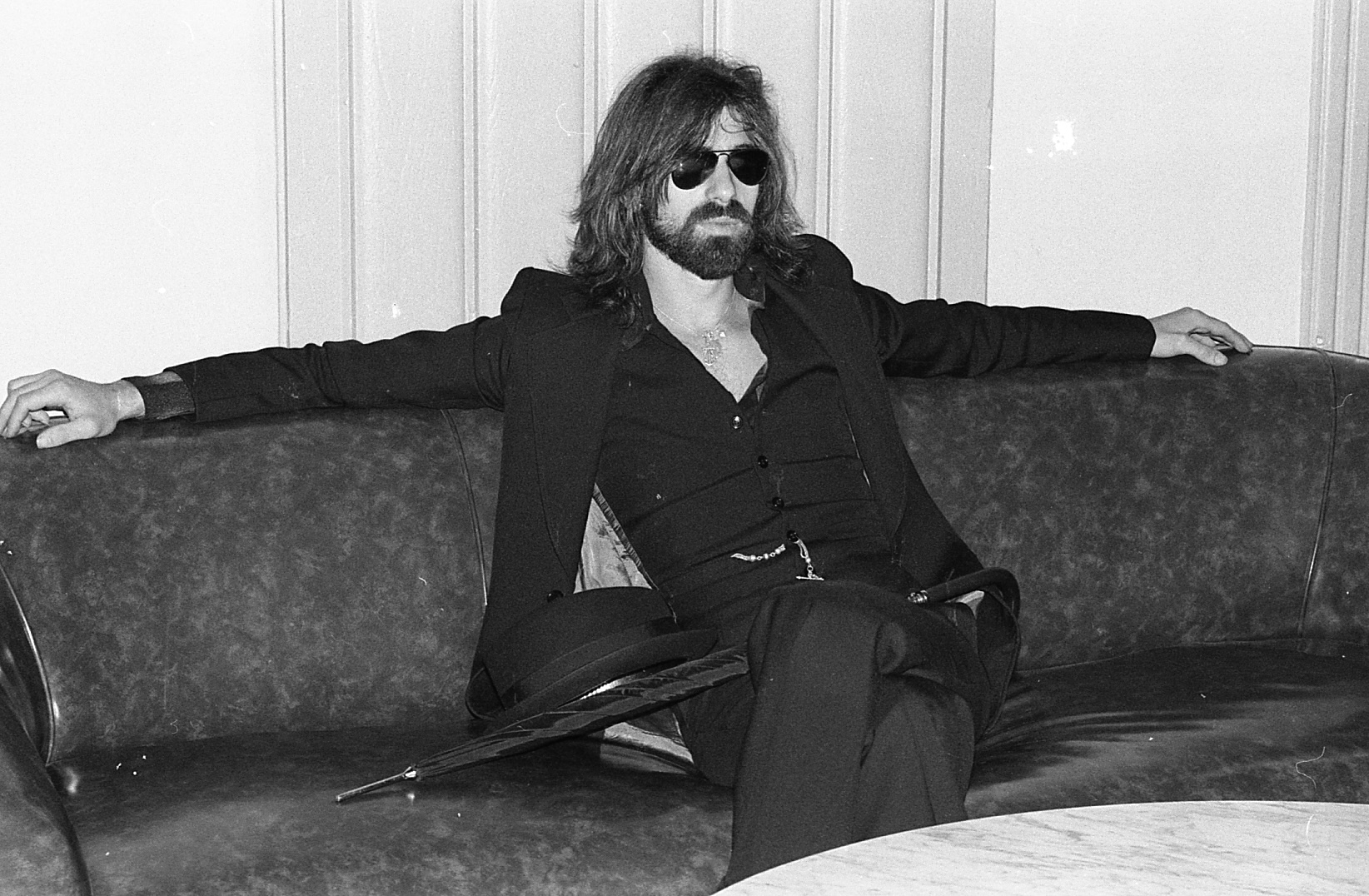

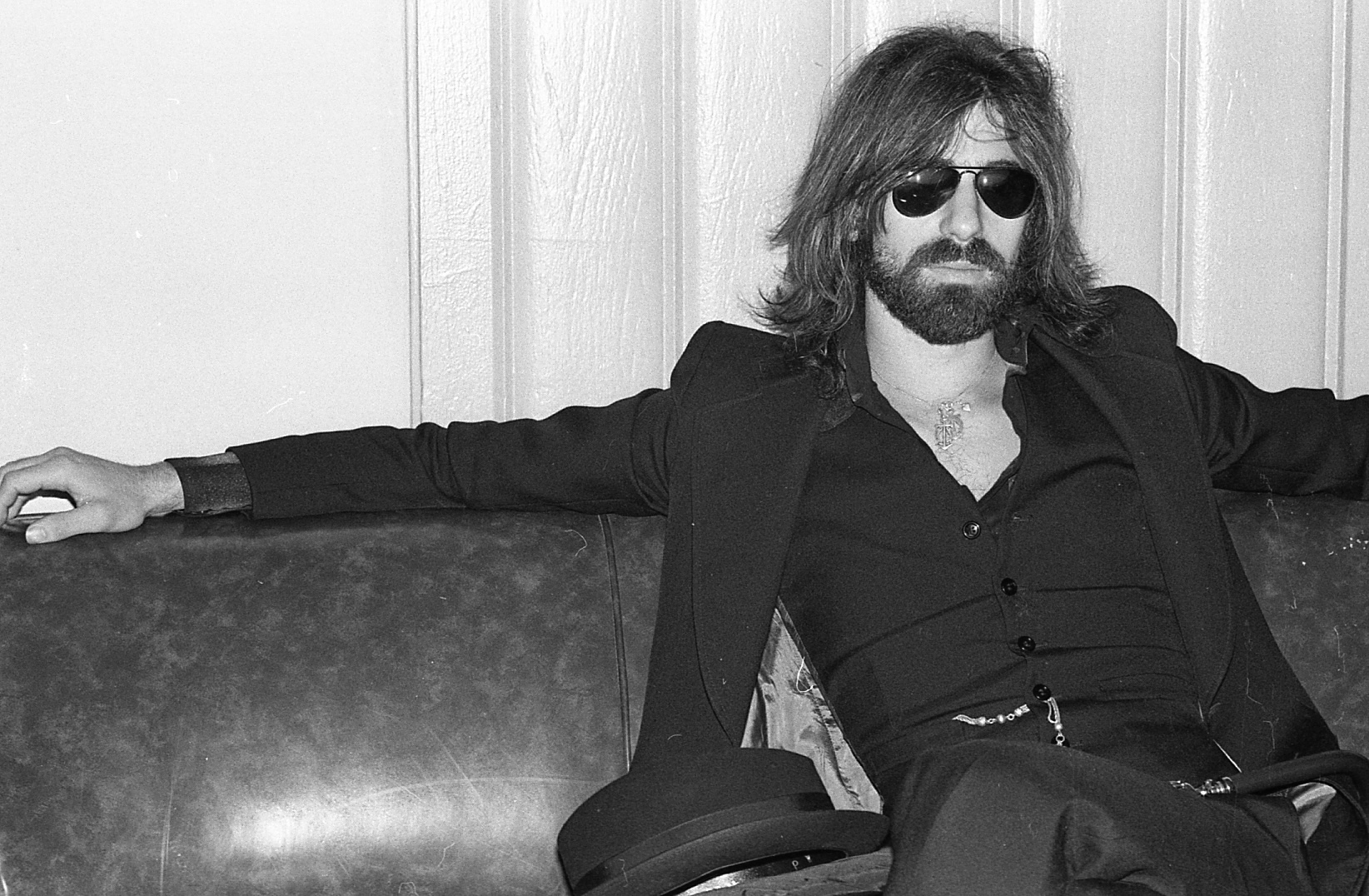

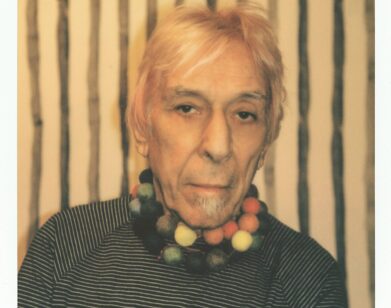

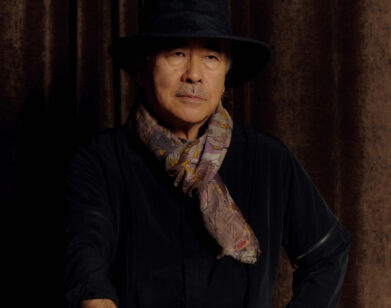

Peter Wolf, onetime lead singer of the J. Geils Band, is a rock star, pioneer radio D.J., painter, sex symbol, A-list wit, and now, with the publication of his memoir, Waiting on the Moon: Artists, Poets, Drifters, Grifters and Goddesses, a best-selling author. Last month, just after the book’s release, Wolf sat down with Danny Fields and Gillian McCain at Fields’ West Village apartment to talk about people they’ve known and adored. And although Wolf and Fields have been fond friends for over 60 years, it had been decades since they’d been in the same room. Below, the trio discusses Factory Superstars, the backroom at Max’s, and how Iggy Pop met David Bowie.

———

GILLIAN MCCAIN: Peter, I love the chapter in your book about Ed Hood. How did you meet Ed?

PETER WOLF: Ed and I lived in a building called Craigie Arms in Cambridge that was filled with writers and musicians. Very cheap rent. Everyone’s apartment looked like what you would expect student apartments to be, except Andrea’s. Her apartment looked Moroccan. She had things hanging on the walls, and incense burning; she was like a spider to the web. She would lure in George Benson, the jazz player, or the blues guitarist, Buddy Guy. She was tall, thin legs, all leather-clad. And in those years, full leather was highly unusual. Our friend, Ed Hood, lived there, too. When you walked into his apartment it was like walking into the Warwick or the Four Seasons. He was the only one who had floor-to-ceiling curtains, and you know, a couch, paintings… Andrea’s the woman Ed Hood has the fight with in my book in the chapter called “Ed Hood and Andy Warhol.” I had just moved in, and she lured me up to her apartment to seduce me. When Ed realized this, they had a war. Ed said, “I’m going to get to him first.” Andrea said, “No, I’m going to get to him first.” So Andrea got to me first and while I was up there, Ed starts banging on the door, “Andrea! Andrea!” When she finally let him into her apartment, Ed had poetry books and bourbon under his arm. “Hood here!” And that’s how I met Ed Hood.

DANNY FIELDS: Was this in Ed’s building on Mount Auburn Street?

WOLF: Yes. It was one flight up, and you could always tell when Ed was busy because the blinds were down. And when the blinds were up, you could see him from the street, parading around, smoking theatrically, always dressed in a suit, starched shirt, and a tie. Always completely immaculate. And very formal. Southern. Came from Alabama. And had this handshake. “Hood here!” He had cards that said, EDWARD MANT HOOD that he would give out. Danny, you went to Harvard, right?

FIELDS: I was enrolled at Harvard Law School for the lesser part of a year. In ’59, ’60.

WOLF: And you met Ed Hood when?

FIELDS: Harold Peterson took me to meet Ed, or maybe we all met at the Hayes Bickford cafeteria. Harold had described him as a graduate student at Harvard, putatively working on his PhD on the theme of love in Shakespeare.

WOLF: You know, Ed almost got kicked out of Harvard.

FIELDS: Was Ed being naughty there? Cruising the men’s room…?

WOLF: What happened was that his “social life” spread to some of the freshman, and to some of the faculty, and…

FIELDS: That’s what a university is for.

WOLF: Also because of the notoriety of 122 Mount Auburn Street, and that many of the freshman would find their way there, and then it worked its way up to the faculty and it became somewhat dangerous for Ed because this one might tell that one and that one might tell this one. He got pretty notorious when Warhol’s movie My Hustler came out in ‘66 and Ed was the star. It was the straw that kind of broke the camel’s back. I remember the screening of My Hustler—and you might have been there—at the Moondial, which later became the Boston Tea Party. Ed is sitting down in the audience—it’s dark in the theater—and everyone’s watching the screen. Then Ed stands up, turns around, takes a cigarette out, and then takes the lighter, and holds it so everybody can see his face in real life while he’s on screen. He slowly looked around the audience as if to say, “Here I am.” And then of course, you hear, “Sit down, Ed!”

MCCAIN: Danny, did you show Peter Ed’s diamond?

WOLF: Yes, I see it from here. It used to be on Ed’s table.

FIELDS: It was a great prop for him. Just a huge glass paperweight, but Ed called it “the diamond as big as the Ritz,” like the F. Scott Fitzgerald novella.

WOLF: Sometimes, when someone else became the center of attention, Ed would throw the diamond onto the floor. Then he would bend down to pick it up and say, “Oh, sorry, my diamond!” That was his way of interrupting and stealing the moment. You know, someone might say, “When I first met Andy Warhol…” and Ed would be crawling around on the floor, “Has anyone seen my diamond?” But you know, the one man who Ed considered to be beyond him in intelligence was Donald Lyons. And Donald insisted that Ed was beyond him—and the two of them would go back and forth. I don’t think Donald took to me until later on. We were polite, but he was curt. I was an interruption if I came by and Donald was there to see Ed. I wasn’t on their level, nor pretended to be, but later on Donald and I became friendlier. Danny, you were close with Donald, of course.

FIELDS: Very.

WOLF: I was witness to the great arguments between Donald and Ed. Like arguing over what should be on the list of the 20 Greatest Films. Ed’s number one was Gone with the Wind. Donald’s was The Golden Coach.

FIELDS: Sunset Boulevard… All About Eve…

WOLF: And then there was the two of them doing their Bette Davis imitations.

MCCAIN: Who did it better?

WOLF: Well, it depended on the night. It depended on the alcohol. Because they both could put it away. One time, when Ed’s mother, Myrtle, was visiting, I had just walked out of my building and I heard this yelling, this commotion, because he lived on the first floor. I came running in and Ed was on the floor in his robe—he had that striped Japanese robe—and his mother was hitting him with her cane. “Ed! Ed! Where’s my bottle?” And he’s screaming, “Ma! You give me my bottle and I’ll give you yours!” And she’s whacking him on the head! She hid his whiskey, and he had hid hers.

MCCAIN: Could one of you explain who Donald Lyons was?

FIELDS: Well, Donald had just graduated from Fordham and was at Harvard working on his PhD in classic Greek and Roman literature. Donald had been a very brilliant child and even in kindergarten, the faculty at his school had him pegged to rise high in the church. The priests said, “Look at this five-year-old! This is Cardinal material.” Like he was at least the second coming, or something.

WOLF: Like the Dalai Lama. So, you and Donald became friends.

FIELDS: Yes, we’d become good friends. After about a week of knowing each other, we started talking about gay bars in Manhattan, because Christmas break was approaching and we were going home to New York City. I was 19, and I had never been to one. We went to the 316 at 316 E 54th, across from El Morocco. That was the first time I ever saw gay boys who looked like they could be my friends. They wore nice crewneck sweaters, and they looked like ordinary cute college guys, but they were gay. And I never knew that existed. I only knew there were sissies. Going to the 316 changed my life. In that year of so-called studying the law, I was studying how to be gay; that you could wear all your J Press and Brooks Brothers and look like an ordinary upper middle class college kid and still be a homo. This was a big adventure for me. And really the study of Harvard Square and the populations therein were much more interesting than Property, or Civil Procedure – the names of classes you take your first year.

MCCAIN: How did you do at law school?

FIELDS: I got a B+ in Civil Procedure, which was supposed to be the hardest course, and everyone fainted, but I never went to class. The other students were so dedicated, they would go to the toilet together and sit in adjacent stalls and talk about law. And I was meeting all these people in Cambridge that I always hoped existed.

WOLF: Why did you decide to leave law school?

FIELDS: Because I hated it. I loved Harvard Square. I hated Harvard Law School. So I moved to Greenwich Village, lived at the Village Plaza Hotel and took classes at NYU so my parents would pay the rent. It was $80 a month.

MCCAIN: Then you started working in magazines.

FIELDS: Publishing was the ultimate for a person who was not really good at anything but was smart. My first job in that universe was at Liquor Store Monthly, which was a trade magazine. It existed to sell advertising of, say, a brand-new kind of bourbon.

WOLF: What was Donald Lyons doing then?

FIELDS: Donald was in Cambridge, and at any excuse I would fly there for the weekend. And when Cambridge people came to New York, they stayed with me.

WOLF: There was a kind of underground railroad from Boston to New York.

FIELDS: Yes. Mainly from Harvard Square. And by then I was Grand Central Station in this underground railroad system. One weekend in Cambridge, I met Tommy Goodwin and fell in love with him like everyone else in the world did. Tommy had just come to New York, and he was expecting to stay at my semi-loft on West 20th Street. I lived for Tommy’s visits. On one visit, he brought two women with him, one of whom needed a place to stay for the weekend. Her name was Edie Sedgwick and she ended up staying for over a month. Now I’m known in history as Edie Sedgwick’s roommate. And if there’s one line that will go on my tombstone, that would be it. “He was Edie Sedgwick’s roommate.” That’s fine with me.

WOLF: How did you encounter Andy Warhol?

FIELDS: Oh, I knew Andy from the San Remo bar, which was really the genesis of everything. Edward Albee, Jasper Johns, Robert Rauschenberg, Peter Hujar, Paul Thek, Andy Warhol and on and on …

WOLF: Located exactly where?

FIELDS: Bleecker and MacDougal, diagonally across from Figaro. Andy would usually be with Ondine and Billy Name. The Factory, i.e. Andy’s studio, had just moved to 47th St between 2nd and 3rd Avenues. Liquor Store Monthly was at 44th and 2nd, so on lunch hour I would just walk up to the Factory, go in, and sit down. That’s all you had to do to become part of Andy Warhol’s crowd.

WOLF: I find this all fascinating because I only know the Factory from the tail end of the Edie era. The whole Warhol crew would come up to Cambridge, and the Velvets did, too. The Velvet Underground were far bigger in New England than they were in New York.

FIELDS: Yes, or any other city in America.

WOLF: My first band, The Hallucinations, played with them a lot. And that’s how I got to meet Lou, and we became friendly. So, was Edie still your roommate when you were hanging out at the Factory?

FIELDS: Oh no. She’d escaped from her upper-class family’s Santa Barbara ranch and was busy reinventing herself. I mean, she was so dazzling. She just lit up the world. Who is that person? But to me, she was someone who left overflowing ashtrays and wouldn’t get off the phone. Oh god, the mess. And she would steal, to the point where I really had to pat her down. Even in front of people as she was leaving the apartment. She’d say, “Danny, what are you doing?” I’d say, “Edie, I’m sorry. Things are just going missing.” A quart-sized bottle of Listerine mouthwash. What a thing to steal!

WOLF: When did Max’s come on the scene? And who put it there?

FIELDS: Mickey Ruskin put Max’s Kansas City there in 1965. Before that, he had a famous gay bar called the Ninth Circle. And then, there was Stanley’s on Avenue B. Then he moved to a nothing restaurant in a nothing neighborhood, which became Max’s Kansas City. His first customers, who were also his friends, were the Abstract Expressionist Heterosexual Alcoholics.

WOLF: So, they left the Cedar Tavern and went to Max’s.

FIELDS: Exactly. Mickey told me they would run up bills over $50,000 and pay Mickey back in art. I still have my bills from Max’s; they’re like $2,000 or something. And Donald would sign his bill “Bugs Bunny” or “Fatty Arbuckle” and give it to the waitress. They would be approved because Mickey was looking for a new crowd. These Abstract Expressionist Heterosexual Alcoholics were not the future. And Mickey was looking for little futures. And then Max’s became a rock & roll hangout.

WOLF: I remember Max’s because I remember the chickpeas. I remember being in the back room.

FIELDS: Mickey thought, until the day he died, that I brought the rock & roll crowd to Max’s, because I had once arranged a press breakfast there for Brian Epstein. I was doing PR for a band Brian and Robert Stigwood were managing called The Cyrkle, C-Y-R-K-L-E. They had a song called “Red Rubber Ball.” It was adorable, and it went to number one. Then Stigwood had this new band that was big in the UK that were coming to New York for the first time to play at Murray the K’s Easter Show, at the RKO 58th Street Theater, and they were called Cream. And I could not get them arrested.

WOLF: I was at that show.

FIELDS: They kept adding act after act…

WOLF: The Rascals.

FIELDS: Mitch Ryder and the Detroit Wheels.

WOLF: Here was the lineup: Mandala, who had one hit, a copy of the song “Love-itis,” then it was the Young Rascals, followed by another band called Cream. And then there was a band called The Who. And they ended their show by destroying their equipment, which nobody had ever seen before. Everybody did three songs. That was followed by Wilson Pickett and the Midnight Movers with Buddy Miles on drums. And then the headliner, standing at the top of a Vegas-type stairway with the band underneath, was Mitch Ryder wearing a sheer blouse. He would do “Jenny Jenny Jenny” and “Good Golly Miss Molly,” dance around like James Brown. And that was the show. The first time The Who and Cream played in America.

FIELDS: And if you went to London, everyone would say, “Eric Clapton is God.” Okay. “Hi, God.” Eric was fucking every groupie in town. He was busy being “Eric Clapton,” and Jack Bruce had a New York girlfriend, so Ginger Baker and I became buddies. Can you picture that couple? And we had dinner almost every night. No one else would have either of us.

WOLF: Ginger was beloved by Ahmet Ertegun.

FIELDS: Oh, you had to belove him. One time an Atlantic publicity executive took me to lunch and he asked me, “What is this rock & roll? It’s getting big, isn’t it? Because we’re having success with the Young Rascals, and this is not in the tradition of Atlantic, like Ruth Brown and Ray Charles.” I mean, it’s 1967. The Beatles had the top five singles in 1964 at the same time. Rock & roll is everywhere and the publicist for Atlantic Records is asking me what it is.

MCCAIN: So, Peter, how did you and Danny meet?

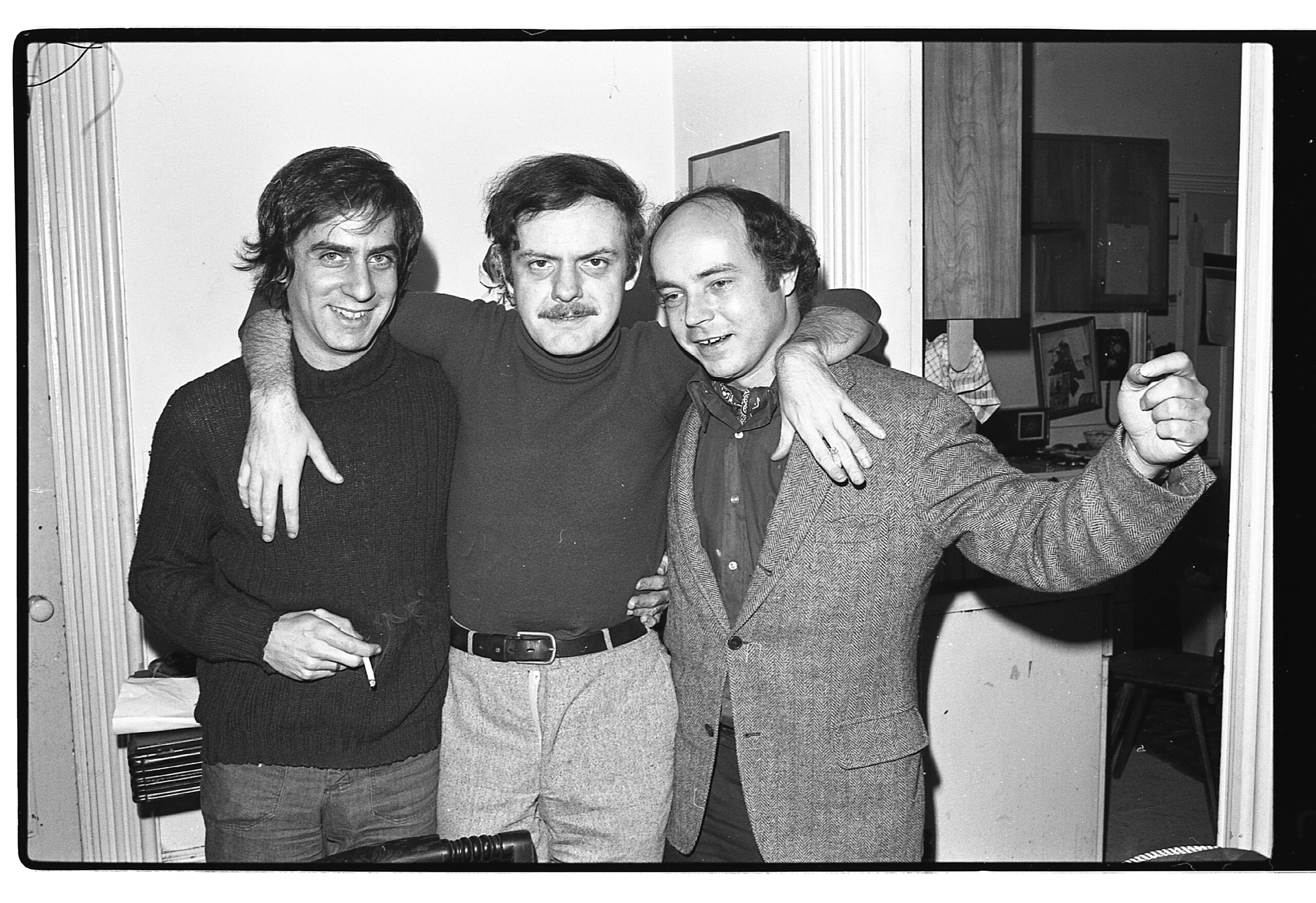

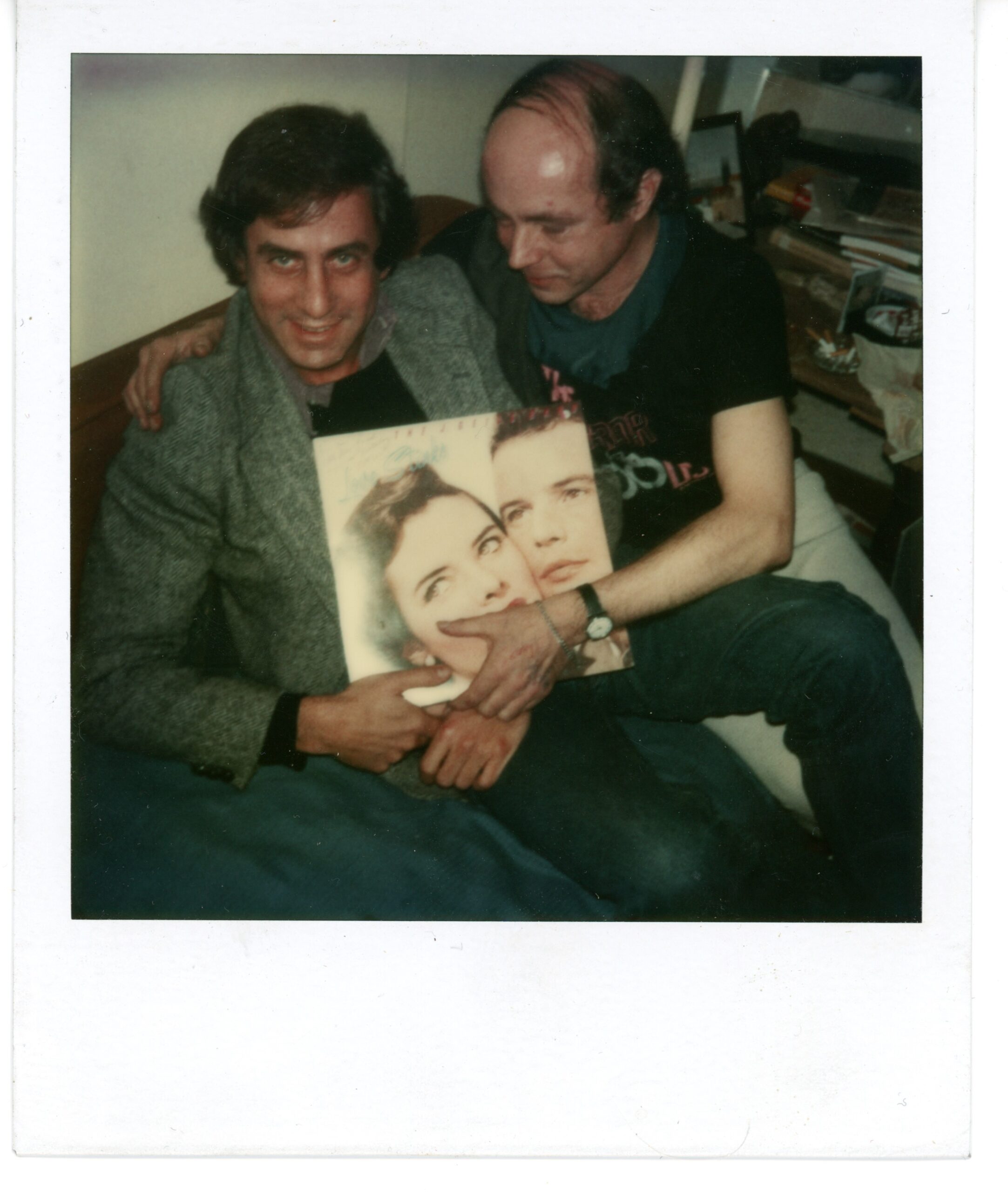

WOLF: We met at Ed Hood’s. Ed and Donald were off entertaining Andy Warhol; they were doing their Donald and Ed act, you know, throwing balls back and forth. Lou Reed was not being friendly.

Polaroid of Danny Fields and Ed Hood holding the J. Geils Band’s LP Love Stinks in 1980, from the collection of Danny Fields.

FIELDS: When the Velvets went to Boston they stayed in and around the salon of Ed Hood. Andy was with them. It seems so organic now because no one was anyone. Andy was sort of on his way to being someone. He was famous then? No. But he was going to be the most famous person in the world.

WOLF: Yeah, the Velvets were crashing at Ed’s apartment all the time; everybody but John Cale. The Hallucinations were opening for them and we would all just hang out. Ed believed early on that the Velvets were going to be incredibly important. He just knew it. And I remember there was a Velvets rehearsal where Lou was yelling at somebody, “We’re going to be as important as the Beatles!” And Ed believed it, too. Ed thought Lou was up there on the mountain. There are a lot of letters that I have between Lou and Ed. Lou would send poetry to Ed. Much later on, when Lou was with Sylvia, we all had lunch and I said to Lou, “I have these letters between you and Ed. Would you like me to you send them to you?” Lou was so toxic. He said, “I don’t want to talk about that fucking faggot. And as a matter of fact, I don’t want to even be near anyone who was near that fucking faggot.” And then just got up and left.

MCCAIN: When you were at lunch?

WOLF: Yeah! Sylvia was stunned.

FIELDS: Which fucking faggot was this? Ed?

WOLF: Yeah, Ed.

FIELDS: What was that about?!

WOLF: I have no idea.

FIELDS: Were they both after the same boy?

MCCAIN: What did Sylvia say?

WOLF: She was so apologetic, and felt terrible. Lou and I were friends; we got along, but something had struck a nerve.

FIELDS: We can’t know what it was, and it was probably something that you’d go, “What? That?” There’s no name for it, and no explanation, but something ticked Lou off. He’s seething 24 hours. He was a drama queen.

WOLF: My relationship with Lou was always very friendly. He would come by my apartment and we would play doo wop records for hours and talk. He and Ed would get into arguments about the poet Delmore Schwartz.

FIELDS: Lou needed to go crazy once every once in a while. There were long periods of okay-ness and then fury.

WOLF: I remember the day I introduced Lou to Bono. To Bono, it was like meeting one of the Apostles. He was enamored by Lou, as was David Bowie.

FIELDS: He was. Lisa Robinson was assigned to bring David and Lou together. And David, oh my god, this story is so famous I don’t even want to talk about it.

MCCAIN: Come on, Danny! Tell the story.

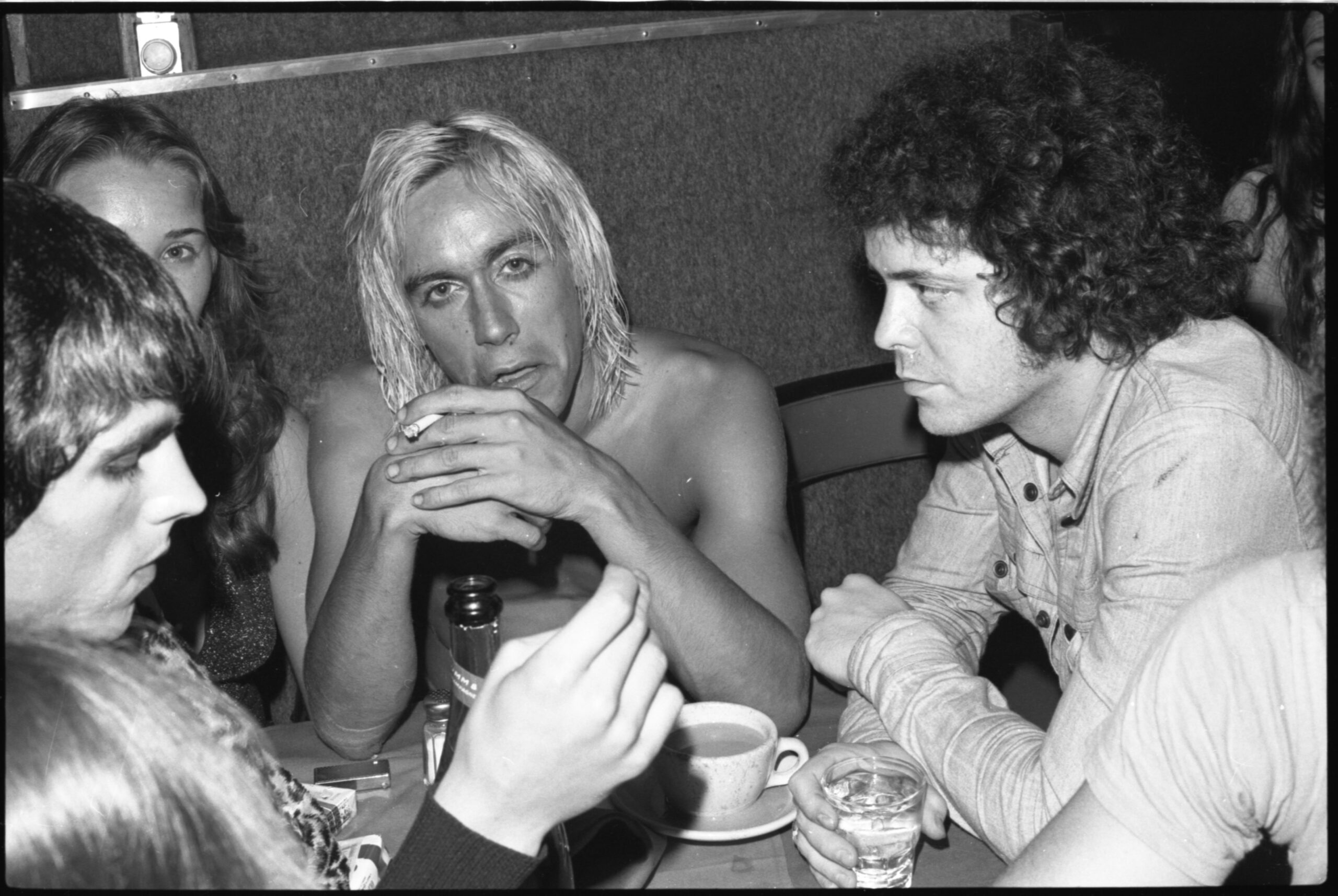

FIELDS: Okay. David Bowie came to New York with a double mission, to meet Lou Reed and to meet Iggy Pop. Iggy was living with me because he had nothing going for him at that time. David said to Lisa Robinson, “Look, I’m coming to New York. Please bring me Lou Reed and Iggy Pop.” She and Richard Robinson took David and Lou to The Ginger Man for dinner and later that night, Iggy and I were at my apartment on 20th street where he was crashing, and I was, you know, “How long is this going to go on?” You love someone very much, but everything was being squandered. He had no life. And this was Iggy! I think we were watching a black-and-white Western on TV, and the phone rang. It was about 2:30 a.m., and it’s Lisa. “I’m with David Bowie. He wants to meet Iggy. We’re at Max’s. How soon can you be here?” “Very soon. Iggy!” “Yeah?” “Get up! Remember when Melody Maker did a poll asking musicians, ‘Who’s your new favorite singer of the year?’ And someone in London mentioned you and we all wondered how anyone could have heard of you over there? Well, that person is very rich and famous and he’s around the corner and he wants to meet you, so get up!” So we walked to Max’s and David was there with his manager who gave gold bars and color television sets to everyone, Tony Defries. We walked in and it was like old friends, sort of. Iggy could really lay it on. “Oh my god! It’s you!” Meanwhile, I had to remind him who it was. David was genuinely in awe of meeting Iggy. And two days later, Iggy was on a plane to London. And that began that. David was brilliant and wonderful, but he was a vampire. Lots of people are vampires. It sounds like Bono was a vampire-in-training. They wanted to know where the magic is coming from.

MCCAIN: Talking about the Lou and the Velvets and people associated with them, did you have dealings with Jonathan Richman in Boston?

WOLF: Jonathan Richman would camp out in front of Ed Hood’s apartment. He’d wait for Lou to come out and then run after him. It was like, “Get away, kid, you’re bothering me.” Jonathan was like a little puppy dog, you know? Just enamored with Lou. He would take a guitar and play outside the window, just do anything to catch Lou’s attention. So, my new band, J. Geils Band, were playing at a place called The Catacombs in Boston—Van Morrison had played there. It was literally subterranean. The Geils Band was doing their first date. So I said, “Hey Jonathan, you wanna open for us?” He said, “Yeah!” I was kind of drunk, and I put a napkin down, and said, “Okay, from here on in you’re now managed by Peter Wolf. Sign here and you have the gig.” And Jonathan signed it. I took the napkin and put it in my pocket, and he went onstage with his electric guitar, and did a tribute to the Who, very loudly. It didn’t go over well. After he finished, I said, “Jonathan, from now on, you’ve got to turn it down. You’ve have to listen to me. I’m your manager now.” So, every time I see him now, I say to him, “You know, motherfucker, I’ve still got that napkin, and you’re still indebted to me.” And he says, “Oh, golly gee…” And I say, “No, Jonathan, I really mean it!”