They Touched You Once, They’ll Touch You Twice: A Renaissance for OMD

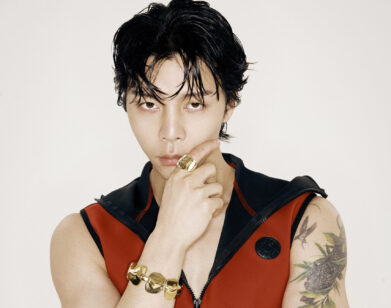

OMD’S PAUL HUMPHREYS (LEFT) AND ANDY MCCLUSKEY. PHOTO COURTESY OF DAVID BROACH

There aren’t many bands that joke as freely about their status as a one-hit wonder as OMD does. There are at least two good reasons: OMD’s “one hit” happened to be one of the most influential, zeitgeist-capturing songs ever to be written. The other thing is, OMD isn’t actually a one-hit wonder. Only in the annals of American pop history do they retain that status. Yet, to their legions of followers, who traced the English band from their Factory Records roots to opening for New Wave icon Gary Numan to, of course, “If You Leave,” they are as influential as the band’s contemporaries—Numan, Depeche Mode, even Joy Division (whom they played with at their first show).

After the original members, Andy McCluskey and Paul Humphries, split in 1989 (with McCluskey officially retiring the name in 1996), their catalogue has been pored over by New Wave fanatics. So after a decade, the duo decided to reform, and in 2010 they released History of Modern, a forward-thinking but nostalgic visit to OMD’s synth-y past. Now on tour in the US, McCluskey still chuckles good-naturedly at the notoriety of “If You Leave.” Sure, it may be their only top 40 hit (in the US; certainly not overseas), but that diminishes their legacy—and their renaissance—not one bit.

LEILA BRILLSON: So, why this tour that includes indie, rock-and-roll-heavy South by Southwest?

ANDY MCCLUSKEY: Basically, we’ve been trying to play America now for the last four years—since we started touring Europe. We finally found agents and promoters that would take a chance on us. Since we were over here, obviously with a new record, our label was keen to get us into town. One of the issues with a band from our era is that there is a certain amount of resistance, in the sense that people often say, “OK, we used to like those guys, they did some good stuff. But, you know, they are just a bunch of middle-aged guys just here to top off their pensions. Why should we be remotely fucking interested in this now?” Which is entirely understandable, especially when bands of our age make new records. They do it because they think they should; they should have a new name for whatever tour they are doing. But actually they have nothing to say, they shouldn’t be allowed in the studio and they make an empty-gesture album.

So it was important to us to make a good album for the right reasons, and actually have something to say—and say it in the right way. And it appears that we’ve done that. It’s been really well received. People have said that we have hit the right balance between sounding like “ourselves” and sounding contemporary.

BRILLSON: Why should people be interested in this now?

MCCLUSKEY: Very few bands have this dilemma, and this dilemma is why we started in the first place. When we started, we were trying to be the “future.” We were trying to eradicate the cliché-ridden, rock-and-roll monster that we hated when we grew up. We were trying to be the future, and that was part of why we wrote our songs, the way we presented ourselves and our artwork. It sounds really pretentious and corny now, but it was our art. We had absolutely no intention or desire to be pop stars. It wasn’t even an option: we were doing stuff that was being influenced by really weird shit. We were doing it because we wanted to, and no one was more surprised than us when songs we had written as teenagers suddenly were selling millions of records.

So that’s our dilemma: What do old modernists do in the post-modern era. Discuss. So that’s why it is important for us to make an album that addresses that dilemma, as well as being a strong album. The one thing that works for us is that what we tried to do 30 years ago seems to have come back into fashion. There is a new generation who have also rejected the stereotypical rock-and-roll monster that reared its ugly head again in the ’90s. A lot of young people are going back and saying, “What these guys were doing 30 years ago is a lot more interesting than this shit. They were actually trying to do something that was intelligent, and beautiful, and melancholy, and not fucking cliché.” That interest has really opened the door for us to have a platform to speak again… in a voice we created for ourselves 30 years ago.

BRILLSON: Just in a different context.

MCCLUSKEY: Right. Now the only dilemma we have is that we have 11 fucking albums, so what should we play? The record company wants us to play the new album to promote it, but—that’s bullshit. Lots of people want to hear different songs. We have a varied audience. We have electro geeks that like the early stuff. Or the passing audience who remembers the few big radio hits. Then there are the new generation that are going, “Oh, these guys are supposed to be the godfathers of electro. We better check them out.”

BRILLSON: OMD has been back together for several years. Why has it taken you so long to release an album?

MCCLUSKEY: The reason why it took time is because we were making a good album. We will release an album when we think we had an album ready to go… By the end of the ’80s, we weren’t happy with what we were. We became a cog in the industry. I carried on for some years, but at the height of Brit pop and grunge, I was sort of banging my head against a brick wall, but I had sort of left grudgingly. When the door opened again—and people were saying great things about us—we took the opportunity to pick up the pieces. But the last thing you want to do when you have a bunch of 20-year-olds saying you are cool is to make a shit album.

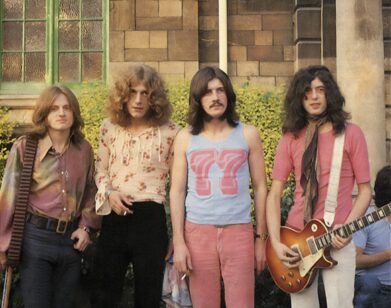

OMD AT SOUTH BY SOUTHWEST. PHOTO COURTESY OF DAN WHITELEY

BRILLSON: Unlike many bands who have a megahit, you guys are very open about talking about the success of “If You Leave.” Why is that?

MCCLUSKEY: Why would you not want to talk about a big success? If we did something we were embarrassed about, we would admit we were embarrassed. We certainly have not hit a home run with everything we have done—we have made mistakes. There are elements of “If You Leave” being a bit of an albatross around our necks in the States because, for people with a passing interest, we were a one-hit wonder. For others who know their stuff, they know that was a key to unlocking a door for us but there is a huge catalogue of other stuff. It was part of something we did, it was great, it was a wonderful moment, and we had a lot of fun.

BRILLSON: Also, to be quite frank, it is also a really wonderful pop song.

MCCLUSKEY: It is a well-crafted song. Some of our more hardcore fans have an issue with it. As I said, we started out trying to be the future, but then we mellowed out, or we realized that trying to change the world with three-minute pieces of music might not actually work. (When you are teenagers, you think music is so important it’ll change the world.) So when we grew older, we accepted that you can be a craftsman. You know how to make something good. It might not be the newest thing you’ve ever done, or you might be repeating something you perfected, but at least you know how to do something good. We are comfortable with something we consider to be “a good piece of craftsmanship.”

BRILLSON: Since we are talking about the past, the cover of your new album is done by Peter Saville, the cover artist for Joy Division, New Order, and Factory Records, and a great graphic artist who really encapsulated a time and aesthetic in music. Do you still feel closely aligned to that era?

MCCLUSKEY: It may seem that OMD and Joy Division come from two different planets, but at the time, we actually had a lot in common—not least the fact that we were on the same label and neither one of us were selling any records! The first time we played as Orchestral Manoeuvres in the Dark, we opened for Joy Division. The second time, we played in Manchester at The Factory (the club owned by Factory Records’ Tony Wilson) and we met these guys who were about to start Factory Records. They were the first people who said to us, “What you do is the future of pop.” We said, “Fuck off, we’re experimental. How dare you call us pop?” But Tony was right and we were wrong.

But some of the darkness and melancholy in Joy Division was something we had ourselves. We just explored it differently. I actually had an opportunity to go and study fine arts at a university, so it was my original intention to design artwork for us. Having met Peter, I thought, “I’m not in his league.” Obviously, he should do it. It was a wonderful association for us. It seemed appropriate to ask him to do the sleeve again. If we were taking the sound we made and turning it into something relevant and contemporary, we wanted the art to reflect that. He took a lot of influence from the Constructivist and Modernists—how do us old Modernists make a new record and a new sleeve? And I think he distilled out a modernist image, but he executed it with computer graphics and bright, modern colors.

BRILLSON: In the pursuit of making something contemporary, what sorts of new instruments, technology or bands did you turn to for inspiration?

MCCLUSKEY: There was no actual need to sit down and do research. We listen to stuff. We are not living in an ivory tower going, “Oh! Music today is not what it used to be!” Paul and I both have studios, and while we had not been working together as OMD, we have been writing songs and making records—both of us are up to date in studio technology. I actually had my first number one a few years ago, writing a song for a three-piece girl group I invented [“Whole Again”, by Atomic Kitten. McCluskey says: “Everyone hates them. But their first album is sheer beautiful disposable pop.”]. We are big fans of quite a lot of current electronic artists. Some are just derivative and sound like the first Depeche Mode album, but people like Hot Chip, Robyn, The Mirrors, Villa Nah—even Lady Gaga—it’s all great. We listen to it, we know what it sounds like.

OMD WILL TOUR EUROPE THROUGHOUT THIS SUMMER. FOR MORE INFORMATION, VISIT THEIR WEBSITE.