Panda Bear and the Grim Reaper

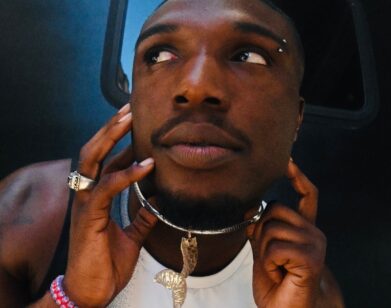

ABOVE: NOAH LENNOX (PANDA BEAR) IN NEW YORK, NOVEMBER 2014. PHOTOS BY KATE OWEN. PHOTOGRAPHY ASSISTANT: SAMANTHA SHANNON.

For the first time in 10 years, Noah Lennox—known by his stage name Panda Bear and also for his part in Animal Collective—is in the United States for a proper U.S. holiday. The 36-year-old Baltimore-native sits quietly in a small recording room at Converse Rubber Track studio in Brooklyn, face brightening upon the arrival of friend and musician Eric Copeland. The two greet each other warmly (it’s the first time they’ve seen each other in at least a year) and digress into their plans for Thanksgiving—Copeland and his wife are hosting dinner themselves; Lennox, his wife, mother, sister, and brother are going be at his aunt’s apartment. After a few minutes of friendly banter, Copeland broaches the topic of Panda Bear Meets the Grim Reaper, Lennox’s fifth solo album.

“I wanted to take it as an opportunity to ask things I probably couldn’t ask you as a friend, that I want to be able to ask just because I’m curious,” Copeland says with an air of determination. Lennox’s mouth breaks into a slight smile, but he blinks and retorts, “That makes me a little nervous.”

After Lennox’s 2007 critically acclaimed pop collage Person Pitch and it’s more minimal follow-up Tomboy (2011), Panda Bear Meets the Grim Reaper (Domino Records) provides an arguably more approachable tone. With music often described as “psychedelic,” the album still includes Lennox’s conglomeration of noise—think wolf howls paired with synths—but the lyrics throughout the 13-song record are more discernable than in the past.

Even though they may not see each other frequently (Lennox currently lives in Portugal), Copeland and Lennox’s musical endeavors certainly cross paths. Aside from being a core member of Black Dice, Copeland and Animal Collective’s Avey Tare form the duo Terrestrial Tones. In 2011, Copeland also played at the All Tomorrow’s Parties festival, which was curated by Lennox, Tare, and the rest of Animal Collective. Their conversation is thoughtful and slow, each word carefully chosen by the two experimental artists. Initially opposing view points on everything from music to death reach levels of mutual understandings and conclusions. –Emily McDermott

NOAH LENNOX: Do you live close to here?

ERIC COPELAND: I live like a 15-minute bike ride away. I live up in Bushwick.

LENNOX: Well, thanks for doing this.

COPELAND: Thank you. I’m stoked to have listened to your record. To be honest, I’ll probably spend more time with that one than any others, because I don’t own any of your other records. [Lennox laughs] I own Young Prayer, but I don’t own the others. I like this one. I think it’s really badass.

LENNOX: Thanks, man.

COPELAND: A lot of sounds remind me of the last Animal Collective record, but you only play drums on that. I was listening to it, and was like, “It has a real similar feel,” but then I was thinking—what was the reaction to that last Animal Collective record for you?

LENNOX: It took me a long time to wrap my head around that Animal Collective album, I think more than the other ones. It’s hard to say why, exactly, but it’s really busy. Spending a lot of time making it maybe primed my brain for listening to music like that, so the impulse was to create environments that featured a lot of elements. I don’t know that these [new] songs feel as busy as some of that stuff, but of course having four people all making six different sounds within a song fills up the space pretty quickly.

But similar to that record, trying to make all the pieces fit was the most difficult thing for this–throwing a whole bunch of stuff at the song and then stripping away all the elements until you’re left with just the vital stuff. In a song like “Mr. Noah,” there’s that swirling stuff, the weird wolf howl, and all that. Trying to figure out what was the essence of the song took a while for both albums. I feel like ultimately, with this one, it became vocals and drums. Most of the mixes seem like that to me.

COPELAND: Really? Because the drums, to me, took a real subordinate, kind of background…

LENNOX: I think part of that is the fact that when I started the songs, they all started with drum breaks. The singing came at the end. It’s one of those things where—and I find this a lot with Animal Collective music—one of us has written the song, so the image of the song is very clear in our brains, but the song eventually gets put in this weird costume. It becomes impossible to be totally objective about it. It’s almost like your brain is imaging stuff that isn’t so clear anymore. So having started the song with just drums, I imagine it’s one of those tricks, where to me it still sounds really drum-heavy, but maybe it’s not.

COPELAND: I mean I’m just surprised…because your vocals, that’s your obvious signature. The drums, to me, are very kind of straight. They keep everything together.

LENNOX: That could be it, too. One of the only consistent features of most of the songs is the drum, so perhaps that’s why it appears to me as a prominent feature. That and the voice are kind of the only things you can grab onto, because it’s not darting all over the place all the time.

COPELAND: So when Animal Collective’s last record, Centipede Hz, came out, it was kind of a game changer for you guys, right?

LENNOX: How do you mean?

COPELAND: Honestly, I feel like I watch you guys have these growth spurts with every record, and with that one I didn’t see it. Is that fair to say?

LENNOX: Yeah. If there was any sort of growth, it was downwards. In terms of people at the shows and stuff like that, it was down. Whether creatively it was down, I wouldn’t say it was, but sometimes I feel like I can only figure stuff like that out after 10 years, having time away from it. I feel like it’s still too close for me to really say.

COPELAND: I’m not suggesting it was a step down creatively. I think that would be unfair to say about almost anybody. But it did seem like maybe people weren’t as excited. Then you also did this Daft Punk song, “Doin’ It Right”, which people creamed their faces over. Do you feel like those were in your mind when working on your own stuff? Or is it something where you’re not answering to anybody?

LENNOX: I’m not the kind of person who actively wants to hide myself from that kind of stuff. I’ll read [reviews], but it’s the same thing with performances: if I felt like we played well—even if the response in the crowd was really bad—I’ll feel pretty good about the show.

COPELAND: Even by yourself?

LENNOX: Yeah, even by myself I’ll feel that. When I perform solo, especially recently, it’s just me, Chris [Freeman], and Danny [Perez]. If one of those two guys is super bummed on the show that will effect how I feel about it. You [only] get one or two shows a year where Chris is like, “That sounded pretty good,” but as long as he didn’t think it was bad and Danny felt pretty good about his side of things, then even if the reception wasn’t great, I’ll usually still feel pretty good about it. If I look hard enough, I can find somebody who really enjoyed the thing or really hated it. It’s where you direct your attention a little bit. Of course it’s there in my brain somewhere, but I think most of the time I’m trying to shut that voice out as much as I can.

COPELAND: So what was the first song?

LENNOX: It eventually became a song called “This Side of Paradise,” which is on the EP, not the album. It’s the first thing I did using a drum break where I felt like, “I can do something that doesn’t feel like I’m putting on a costume or just doing something that’s a copy of something else.” I think it was a zone I was little afraid to go to before. Once I had done that and a couple other little pieces of songs, I felt like I’d found a way of using that stuff in a way that felt like it was still me doing it.

COPELAND: And what was the last song you did?

LENNOX: [pauses] Probably “Lonely Wanderer.” It’s one of the slower ones.

COPELAND: Were you working on this while you were doing Centipede Hz?

LENNOX: When we were recording that one in El Paso, at nighttime, just trying to get my head away from the other stuff for a while, I would make these little things on the computer and that was one of them.

COPELAND: So I was listening to the album, and this is a really dumb question, but what are you singing about? I listened to the EP, I found it online, and there was [only] one song where I could understand every word.

LENNOX: It’s different.

COPELAND: It wasn’t, actually. It still sounded a lot like you and I appreciated it. But when I went back and listened to the rest of the album, I felt like I only caught a phrase or maybe an indication of something. Is that important?

LENNOX: I have mixed feelings about it. I think a lot about what the words are, what they mean to me, and what they might mean to someone else. There’s a lot of work put into that, particularly this time around. So it is important, but I think oftentimes it can be so revealing that, for me, it’s embarrassing or there’s a fear or shyness about what’s being said. Oftentimes the impulse will be to hide it or make it secret in a way.

I still did that, I think, this time, but in a very different way than before. Before it was affecting things in ways that would still feel good within the rest of the song, but they would make it much harder to understand what was being said. Whereas this time, it was more in the choice of the words and making little riddles that would make the messages of the songs a little less straightforward.

COPELAND: Do you have a lyric book in the record?

LENNOX: Yeah. Pete [“Sonic Boom” Kember], who worked on the music with me for the last one and this one, is always suggesting that I put the lyrics in a little book that comes with the album. This time we’re doing a poster that’s going to come with the first batch of records that has all the lyrics on the other side. But again, I feel like it’s probably fear more than anything that prevents me doing something like that. Although, I did Person Pitch two albums ago [and] once I thought about the fact that I was probably being kinda lame and hiding words, I wrote them on MySpace or something like that and put them up on the internet for people to see. I didn’t want to feel like I was cowering.

COPELAND: It’s strange, though, because it seems like that’s what people respond to a lot. I feel like when I’m out and people want to talk about you, it’s always this impression that is based on these decisions you make, which to me are kind of misrepresentative. Where it’s childlike or whimsical…

LENNOX: Choirboy?

COPELAND: Well, yeah, but I look at you and I don’t think that.

LENNOX: I feel like in a conversation if things get said and then repeated, it sort of becomes inherently part of the narrative whether you want it to be or not. I think there’s a bit of that going on. I certainly don’t feel like anything I’m writing about for these songs has anything to do with children or childlike environments or anything like that.

COPELAND: So what are you?

LENNOX: What am I talking about? [pauses] I couldn’t say it’s a concept record; there isn’t a theme to it. There’s a lot of animal-people relationships, people as animals, sex, individualism. They’re very large things and that was intentional. I felt like introspection was something I’d done a lot previously. The hope was, of course, to do a diary—show the good stuff and the bad stuff that I felt like I was noticing in myself—in the hopes that somebody else could see it and learn something. I feel like introspection is good, but after a certain threshold it becomes narcissism or self-centered. I suppose having children pushes that notion quite a bit, so for various reasons it was important to feel like I was writing and thinking about something larger than myself, stuff like the things I was mentioning before. One song is about disease. I wanted the subjects to be larger and more globally important.

COPELAND: The titles kind of suggest that.

LENNOX: You think so?

COPELAND: A little. I thought they related to myths or something that is more globally shared.

LENNOX: I hadn’t really thought about that, but it’s true.

COPELAND: When I listen to your record there’s this vocal component and then I think of sequencing. I think of sequencing a lot in my life, so I was just wondering what it’s about. When do you consider your record done?

LENNOX: Another really good suggestion that Pete had was to record a lot of songs. We went into the studio and I was like, “I got these six or seven songs that I think are good. We’ll do those. Let’s just focus on those.” We would always spend about half the day on any given song and then both of us would get sort of tired of it and go to something else. We got maybe half of those seven songs done and then Pete was like, “Why don’t we do this other one? This other little thing you played me, just make something with that?” So we wound up recording 19 songs and I’m really glad we did because I feel like having the flexibility of that many songs made it a lot easier to make a collection of songs that told a story.

I wish I could say that I had a master plan and a game plan to make this thing, but it was more like once we had those 19 songs I could select songs that I liked, but also a group of songs that when arranged there was a narrative or story arc to them. Ultimately, the way it made sense to me was the first five or six songs feel like an identity that’s breaking apart. They’re the more hectic songs; there’s often more stuff in them; there’s more confusing moments in them. The whole thing feels like it dissolves to the point where there’s a trumpet call in a song called “Tropic of Cancer.” It feels like this very deep, almost desert-like space…that song and “Lonely Wanderer” are meant to represent–or the way I understood it once I put the sequence together–the times in my life that I’ve gone through a really dramatic change of character or something has happened that really caused an explosion mentally or spiritually in my life. That transitional place has often felt really cold, barren, and difficult. Within the story arc of the album, I felt like after that trumpet call, it signifies that limbo state.

Those are the songs that don’t really have any distinctive rhythm. They kind of just float around. I like those two songs occupying that space. It’s meant to be the bridge between the old identity and the new identity. Then the first song after that, the first song where the new thing is becoming what it is, of course has relation to the old identity, it’s still the same person, but the voice in that “Principe Real” song has this other weird synthetic component to it. I think I played the singing part and then Pete vocoded that using the vocals.

Within the story, it worked for me because it was like that identity hadn’t become itself yet, so it was this alien, not fully human sounding thing. It’s a little rocky at the end where the new identity is becoming itself, but the last song feels a bit triumphant–maybe in a bordering on cheesy way, but cheesiness can be effective. The last song, “Acid Wash,” feels like it’s looking back at this story, this change that’s happened, and it’s not entirely positive, but it does feel like an ending and a beginning.

COPELAND: The last song feels like it has a little bit of a humorous ending.

LENNOX: I feel like there’s a lot of humor throughout the songs. I wanted the music to sound fun, especially after the last album, which felt really severe and serious. But I also felt it was almost like a Trojan horse: grabbing somebody’s attention with something that felt really fun, fresh, and easy to digest, and then you secret in this twisted stuff.

COPELAND: The title?

LENNOX: The title works in that way too, I hope.

COPELAND: You think it’s in jest?

LENNOX: Humor in music is a tough one. [sighs] I don’t know if “in jest” is the right way to say it. To me, it feels lighthearted. It didn’t feel heavy-handed to me, despite invoking death. I guess the hope is that it would suggest that death isn’t really what I’m talking about.

COPELAND: Even though it kinda is?

LENNOX: It’s not really, though. None of the songs talk about dying.

COPELAND: But you’re bringing it up in an esoteric form or idea of death, where your identity dies and you’re reborn.

LENNOX: A type of death, I suppose, it is addressing. But not death, like everything is gone.

COPELAND: Do you think about being an American ever?

LENNOX: Sure.

COPELAND: Do you identify as one? What’s your passport?

LENNOX: I have a U.S. passport still. I’ll always think about myself being an American.

COPELAND: That’s probably even a big part of your daily suit. Like you walk outside…

LENNOX: And I’m not like everybody else?

COPELAND: [laughs]

LENNOX: Don’t laugh! [laughs]

COPELAND: Yeah, and there are things you can’t access because of that.

LENNOX: Language is the toughest thing, though.

COPELAND: Not stigma?

LENNOX: I assume you’re talking about Portugal?

COPELAND: Or in general. You can talk about Portugal, but I know that you travel probably half the year as well. There are some ideas in the sound that I was like, “I wonder if he battles with [being an American]? I wonder if he even thinks about that?”

LENNOX: I think about it a lot.

COPELAND: In your music do you think about it? There was one song especially that had a ’50s melody and there was one that I thought had a “Southern Nights” [by Allen Toussaint] sample, and I was like, “I wonder if that makes a difference to him…”

LENNOX: I’m sure it does, but it’s hard for me to say exactly how. Anytime there’s an obvious reference point—and this goes for all the guys in the band I think it’s safe to say—the impulse is to abstract it. So it’s hard to say, or if there’s a really obvious influence, I failed. But I feel like everything we listen to, everything we experience, gets represented when we spit out stuff, but it’s often difficult to trace those lines. When you create something you leave little crumbs of stuff that you’ve experienced or music that you’ve listened to. I feel like it all makes it way out.

COPELAND: Like there’s residue that you can’t control?

LENNOX: Sort of. Maybe they’re just like clues.

PANDA BEAR MEETS THE GIRM REAPER IS OUT TOMORROW, JANUARY 13 VIA DOMINO RECORDS. FOR MORE ON LENNOX, VISIT HIS WEBSITE.