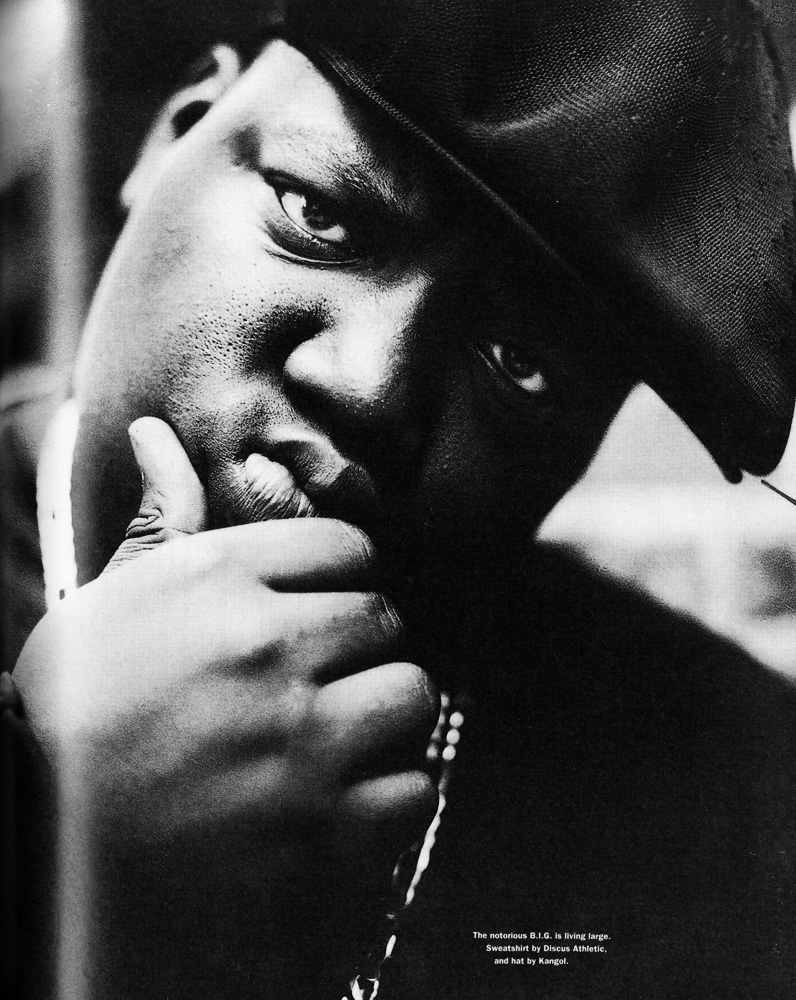

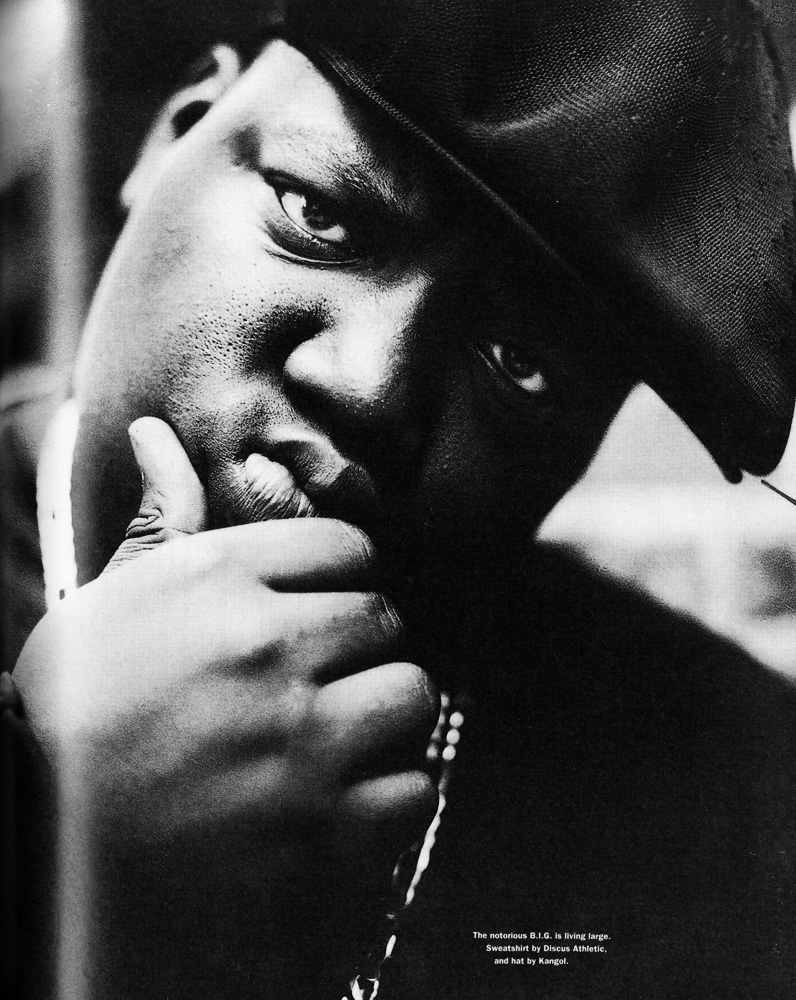

New Again: The Notorious B.I.G.

Variety recently reported that TBS is developing a scripted television series based on a surprising subject: the lyrics of The Notorious B.I.G. The record label Mass Appeal is involved, which bodes well for show—which is currently titled Think B.I.G.—but we can’t help but wonder how they will incorporate, “I love it when you call me big poppa,” into the show’s storyline. To make the wait easier, we’ve reprinted Biggie’s feature from our November 1994 issue here. It was a time of change for the artist, who had just cemented himself as a hip-hop staple with the 1994 release of his debut LP Ready to Die (Bad Boy Records). He reflects on his time as a drug dealer in Brooklyn, hiding that job from his mother, and his career blowing up.

B.I.G.: Rap’s Next Big Thing

by Havelock Nelson

The Notorious B.I.G. is on the set of fellow rapper Craig Mack’s new video for a remix of “Flava in Ya Ear.” B.I.G. is guest-starring with Busta Rhymes, Rampage, and L.L. Cool J. Dressed entirely in black, B.I.G. is taking turns being in front of the camera; hanging outside with his homeboys smoking blunts; and lounging with his wife, Faith Evans, a singer signed to Sean “Puffy” Combs’s Bad Boy Entertainment, the label that also boasts Mack and B.I.G. himself.

While Mack’s album revels in the abstract art of spacey boasting, B.I.G.’s disc, Ready to Die, deals in straight-up reality, giving listeners a vivid picture of his life in urban America. Not since Ice Cube‘s AmeriKKKa’s Most Wanted in 1990 have hip-hop and cinema verité been crossed so effectively. Ready to Die offers a series of rap theater pieces that run from the performer’s birth to a dramatization of his death, a symbolic suicide. It shows glimpses into his childhood struggles and black-mafia past, while also serving doses of dark humor and good-time fun.

HAVELOCK NELSON: Tell me about a typical day in your life now.

THE NOTORIOUS B.I.G.: Basically, I wake up at nine o’clock in the morning, go to different record stores, go to the studio, think up different ideas for songs. Just workin’.

NELSON: How is a typical day now different from before you were making records?

B.I.G.: Well, before I was just on the corner, selling drugs with my niggas. I’d wake up around nine o’clock to catch the check-cashing place at nine-fifteen. The crackheads get checks from Social Security, and on Saturday they get all their welfare checks. And when they cash those in, they’ll usually want to buy drugs. So we’d be up early—as soon as they get their money, we’re going to be the first people they see.

NELSON: Where was your territory back then?

B.I.G.: Fulton Street [in Brooklyn] between St. James and Washington Avenue.

NELSON: Hanging out on the corner and seeing everything that was going on, did you ever feel that you might be a target for someone who didn’t want you to know the things you know?

B.I.G.: What happens on that corner happens on every corner. I’m immune to it. It’s everyday living for me. We were seeing niggas get hit all the time. The only time hearing somebody got killed is a surprise to me is when it’s somebody I was close to. Then, I have mourning for them. But just to hear “Blah-blah got smoked” is nothing to me. It’s just average shit.

NELSON: How did you get started dealing drugs?

B.I.G.: This was just basic living, you know what I’m saying? Everything was happening on that strip of Fulton Street. And if I wanted Chinese food, if I wanted to play video games, if I wanted pizza, if I had to go to the corner story for a juice, I had to go on Fulton Street. So I was witnessing it every day. I knew niggas was gettin’ money, and I knew they were selling drugs. I knew they was fly as hell—they had hundred-and-fifty-dollar Ballys on and bubble gooses and sheepskins, and I was like, “Oh shit. These niggas just doin’ it.” And then I heard about crack on the news and I was like, “Oh, that’s what the niggas must be doing.” And when I kept coming outside, I was doing my own little jostlin’ to get my money.

NELSON: What kind of stuff were you doing?

B.I.G.: Snatching pocketbooks and shit like that. Going to the bank machines and catching somebody getting money out of the machines. I couldn’t let my moms know I had all that money, so I couldn’t buy no sneakers or nothing because I couldn’t bring them in the house. It got to the point where I used to hide all my clothes on the roof. Then my next-door neighbor said, “Yo, why don’t you take some of that money, and we’ll go to the corner and get our thing going.” He was hustlin’ and he had big four-finger rings and Fila suits and Ballys. And I was like, “Fuck it. Might as well.” He brought me on the avenue, and I just started going it from there.

NELSON: How did you keep it from your mother?

B.I.G.: I used to just cheat and lie. She used to ask me where I got my stuff from. She’d see pictures of me with my gold teeth and my chains and stuff. She didn’t know what I was doin’. My mom is from Jamaica and she was going to school in the morning, and in the evening she was working, and at night she would go to night school and then come in and go to sleep. So she would never watch the news and stuff like that and she didn’t know what crack was. She didn’t know nothing about it, but when I told her I was selling crack, she threatened to kick me out of the house. And then I just started paying for stuff—paying her bills and giving her money, so she’d just tell me to be careful because there was nothing she could do to stop it.

NELSON: She just accepted what you were doing?

B.I.G.: I’d never say she accepted it. I was basically uncontrollable. I wouldn’t stop, no matter what. I had gone to jail, but I wasn’t gettin’ locked up for drugs then. I was gettin’ locked up for guns. My moms kept finding guns and stuff in my room and she was gettin’ more scared.

NELSON: She didn’t throw you out again?

B.I.G.: No, because I moved. I went down South, because I started getting up on a little out-of-town connections. What we were selling in Brooklyn, you could sell for four times that in North or South Carolina. I went down there for about two years. And then I got locked up bringing some weight from New York to North Carolina.

NELSON: How long were you in jail?

B.I.G.: Like, about nine months.

NELSON: Did your mom know where you were?

B.I.G.: Nah.

NELSON: And how old were you at this point?

B.I.G.: Maybe seventeen. I finally had to tell my mom that I was locked up, because she was the only one who could get me the bondsman. Then she got me the bondsman, and I got out on $150,000 bail. I had gotten money from an accident when I was younger—I broke my foot—so I had money in the bank, and it had accumulated up to, like, about $80,000. And my mom put up some more money. We paid the bail, and I never went back to court.

NELSON: Is that settled now?

B.I.G.: No, it’s not. It’s still pending. I’m hopin’ that the judge will be lenient. They got $150,000 out of the deal. And it ain’t like I’m selling drugs. I’m trying to get other niggas off the streets.

NELSON: Tell me about your dad.

B.I.G.: Fuck that nigga. He jetted when I was two years old. Never heard from him since then.

NELSON: Did you have any male role models?

B.I.G.: Nah. The hustlers on the corner were my role models.

NELSON: You still live in the same apartment. Is it hard to hang out on the same corner where you used to sell drugs?

B.I.G.: Hell yeah, man! Sometimes I be jealous of them niggas, because even though what I was doing was dead wrong, we still had mad fun.

NELSON: Tell me what the fun part was.

B.I.G.: Going shopping all the time. Just making money, and competing with the niggas in other neighborhoods. And the whole competition with the girls—who had the prettiest girlfriend—and going partying. It was just on. It was fun!

NELSON: But you’re still making money.

B.I.G.: Yeah, but it’s not the same. Until I get to the point where I want to be, where I’m selling crazy records, and I can bring all my niggas with me to do shit. I’m doing this shit by myself now. I’m lonely! I’m bored! I’ve got my one little man with me—he’s part of my crew, the Junior Mafia. I can’t bring all of ’em, and he’s the one nigga I fuck with all the time.

NELSON: And what does he do for you?

B.I.G.: He’s my hype man. He’ll iron my clothes in the morning. Roll my blunts. Shit like that.

NELSON: How did you hook up with Puffy Combs?

B.I.G.: Well, me and my DJ, 50 Grand, used to make tapes in the basement when we’d drink and get high. I used to just bug on the mike, and he would play instrumental beats and tape them. He let Mr. Cee, Big Daddy Kane’s DK, hear it, and from Mr. Cee it went to The Source magazine, for an album they were putting out, featuring “Unsigned Hype” shit. Then the guy that organized that, Matty C, saw Puff and asked him if he had some new niggas that had some hard shit. And Matt let him hear my shit. It all happened from there.

NELSON: And now your record’s doing really well.

B.I.G.: That’s nothing to me. I mean, when Puff tells me he’s selling this amount of records a week, I’m like, “Is that good?” All I know is gold and platinum, and I want to be platinum. I’m just trying to blow up. I figure if this shit blows up, a lotta other niggas gonna come right behind me and scoop it up more and just bring us all up.

NELSON: Is it hard for you to stay real and blow up at the same time?

B.I.G.: Naaah. Blowin’ up is nothing to me.

THIS INTERVIEW ORIGINALLY RAN IN THE NOVEMBER 1994 ISSUE OF INTERVIEW.