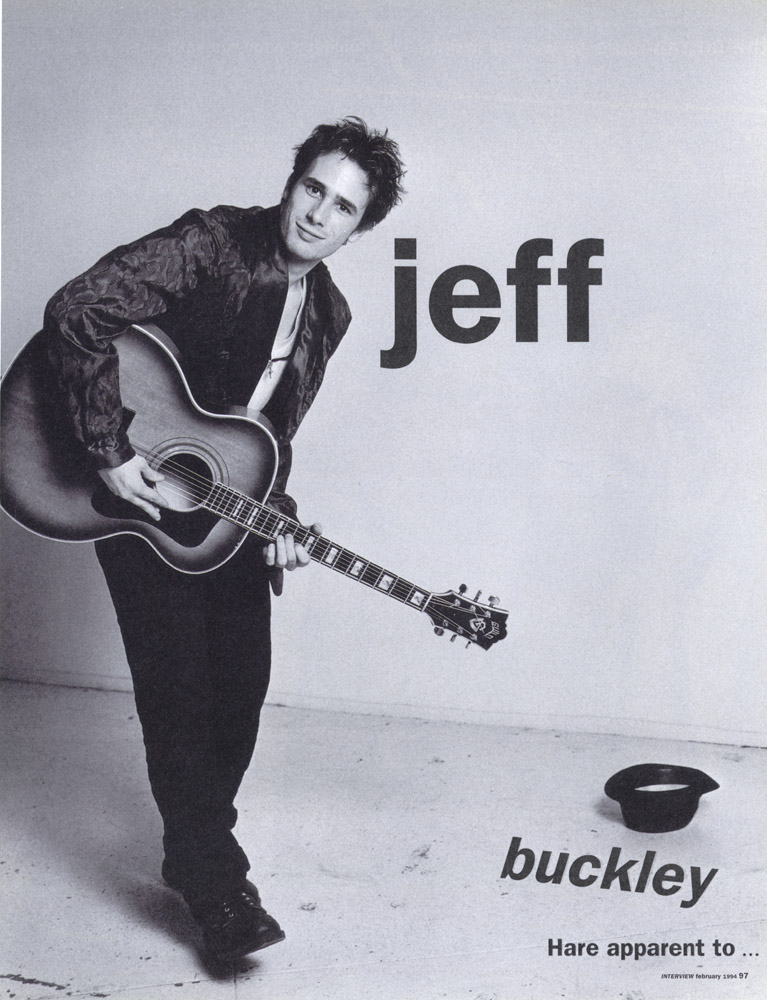

New Again: Jeff Buckley

In New Again, we highlight a piece from Interview’s past that resonates with the present.

Jeff Buckley’s only studio album, Grace, is melancholic and haunting. Almost two decades after its release, it lingers on in popular culture. It doesn’t matter how old you were when Buckley drowned; if you are musically inclined, at one point or another, you will “discover” Grace. First “Hallelujah,” the most popular cover of Leonard Cohen’s 1984 original, then “Last Goodbye,” “Lover, You Should’ve Come Over,” “Grace,” and “Eternal Life.”

Today is the 26th anniversary of Buckley’s accidental death at age 30. It is easy to get swept up by the posthumous mythology surrounding the musician—the idea that he was a doomed, lonesome, tragic soul. Much is made of the fact that Buckley’s absent father, the musician Tim Buckley, also died young, from a drug overdose when he was 28. In an effort to remember Buckley as he really was, we’ve reprinted our 1994 interview with him. In it, he discusses artists he likes (Robert Plant, Nina Simone, Patti Smith), artists he doesn’t like (Michael Bolton), and how he “inhabits” his songs.

Jeff Buckey

By Ray Rogers

Jeff Buckley may have acquired his surname from folk legend Tim Buckley, but that’s it. The 27-year-old singer-songwriter, who met his father just once, grew up with his mom and stepdad in California and was raised on the sounds of ’70s FM radio. Since moving to New York City two years ago, Buckley has become an institution in Manhattan nightclubs, strumming his soul out on an old guitar, playing and singing with a graceful majesty. Leaping from folk to blues to rock-‘n’-roll, Buckley connects the dots with emotional power. The singer will release his full-length debut on Columbia Records in April.

RAY ROGERS: You’ve really created a name for yourself in New York by playing live all over town.

JEFF BUCKLEY: Yeah, I grew up in Southern California, but this is where I blossomed. This place turned out to be everything I knew it would be: it stinks like hell—a fucking majestic cesspool. Art is everywhere. Electricity is everywhere. It’s very extreme. I’m not saying, “It’s a great, wonderful dance,” but it makes sense to me.

ROGERS: You moved here from L.A. after being asked to perform at a memorial tribute in Brooklyn for your father, Tim Buckley.

BUCKLEY: Yes. I decided against performing at first. When my father died, I was not invited to the funeral, and that kind of gnawed at me. I figured that if I went to this tribute, sang, and paid my respects, I could be done with it. I didn’t want my appearance to be misconstrued, so I said: “I don’t want to be billed; I just want to walk on. I don’t want to get anywhere for doing this. It’s something really private to me.”

ROGERS: What did you sing?

BUCKLEY: I sang Tim’s song “I Never Asked to Be Your Mountain.” It was about him having to take the gypsy life over a regular one. I’m mentioned in the song, as is his girlfriend at the time—my mom. It’s a beautiful song. I both admired it and hated it, so that’s what I sang. There are all of these expectations that come with this “’60s offspring” bullshit, but I can’t tell you how little he had to do with my music. I met him one time when I was eight; other than that, there was nothing. The people who raised me musically are my mother, who is a classically trained pianist, and my stepfather.

ROGERS: When did you realize that you wanted to sing?

BUCKLEY: I just always sang. My mom and I would always listen to the radio while driving to school. “Summer Breeze” would come on, and she would sing the second harmony, and I would sing the third harmony. Music was like my first real toy. I was an only child for a while, and I was alone a lot of the time—and I liked it. I still like being alone.

ROGERS: Whenever I’ve seen you play here in New York at Sin-é or Fez, people sit there mesmerized.

BUCKLEY: People weren’t into it at first. I had to fight to be heard. Then I had to stop fighting. Whole months would go by where people would just be talking. I even got a headache from a performance one time.

ROGERS: What changed?

BUCKLEY: I learned how to use everything in the room as the music. A tune has to resonate with whatever is happening around it. So if people are talking, I let them talk. That just means they’re part of the music. I even had to learn the noise the dishwasher makes at this little café; I had to play in B flat or it wouldn’t sound right.

ROGERS: You put so much feeling into your singing. One word goes on for minutes sometimes.

BUCKLEY: Words are really beautiful, but they’re limited. Words are very male, very structured. But the voice is the netherworld, the darkness, where there’s nothing to hang onto. The voice comes from a part of you that just knows and expresses and is. I need to inhabit every bit of lyric, or else I can’t bring the song to you—or else it’s just words.

ROGERS: Where do you find inspiration for your songwriting?

BUCKLEY: People I know. Daydreaming. I daydream too much. I’m not the greatest songwriter, yet; I daydream thinking about great songwriters. I was brought up with all these different influences—Nina Simone, Nusrat Fateh Ali Kahn, Patti Smith—people who showed me music should be free, should be penetrating, should carry you.

ROGERS: When you’re onstage, you give a lot of yourself. What about when you’re offstage?

BUCKLEY: How do I seem right now? This is how I am. I know about the utter disappointment of meeting somebody that is just “putting it on.” If you work at putting it on when you go onstage, you can be ultrafabulous, but when you’re offstage, you’re like a piece of costume jewelry that has no function, like Michael Jackson.

ROGERS: I want to talk about another Michael. I read a review that compared your recent EP, Live at Sin-é, with Michael Bolton’s new record.

BUCKLEY: Oh, my God! Oh, shit, that’s really disgusting!

ROGERS: It gets worse. They said he has succeeded in taking from the tradition of African-American soul and blues singers in a way that you have miserably failed.

BUCKLEY: Really? But the thing is, I’m not taking from that tradition. I don’t want to be black. Michael Bolton desperately wants to be black, black, black. He also sucks.

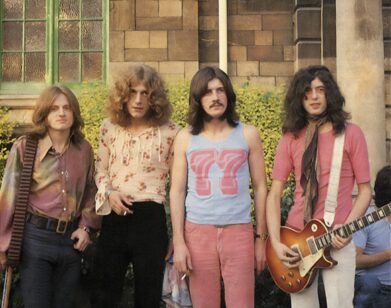

ROGERS: I know Robert Plant was a big influence on you.

BUCKLEY: That’s my man! The cool thing about all those Zeppelin songs is that, because of the way Plant sings, if you put them into a different musical setting, they would sound like R&B songs. With Led Zeppelin, everything was out of tune, and Plant sang wrong notes. But he was the one that showed me that there aren’t any wrong notes.

ROGERS: People talk a lot about how handsome you are. Is it weird to have people drooling over you for how you look?

BUCKLEY: It’s something I’m really wary of. On my record cover, you can barely see my face. I still think I look really geeky. The way you look doesn’t mean shit if you can’t sing, or if you’re mean to people. It doesn’t mean shit if you’re not truthful with yourself. I have very different ideas about beauty than the rest of the world.

ROGERS: What is your idea of beauty?

BUCKLEY: It just is. People have a certain perfection about them, no matter who they are. Like when Janis Joplin sang. Gorgeous!

ROGERS: Is it an uncomfortable compromise for you to deal with all the music industry hype?

BUCKLEY: There are thousands of great artists that wouldn’t be doing the same kind of work if there were no music business machine. The ones who are popular would be doing much different work, too. Michael Bolton would be pumping gas.

ROGERS: Where do you see yourself in 10 years?

BUCKLEY: Still in New York, still trying to get closer to emotions in music. I don’t see myself in an ivory tower.

THIS INTERVIEW ORIGINALLY APPEARED IN THE FEBRUARY 1994 ISSUE OF INTERVIEW.

New Again runs every Wednesday. For more, click here.