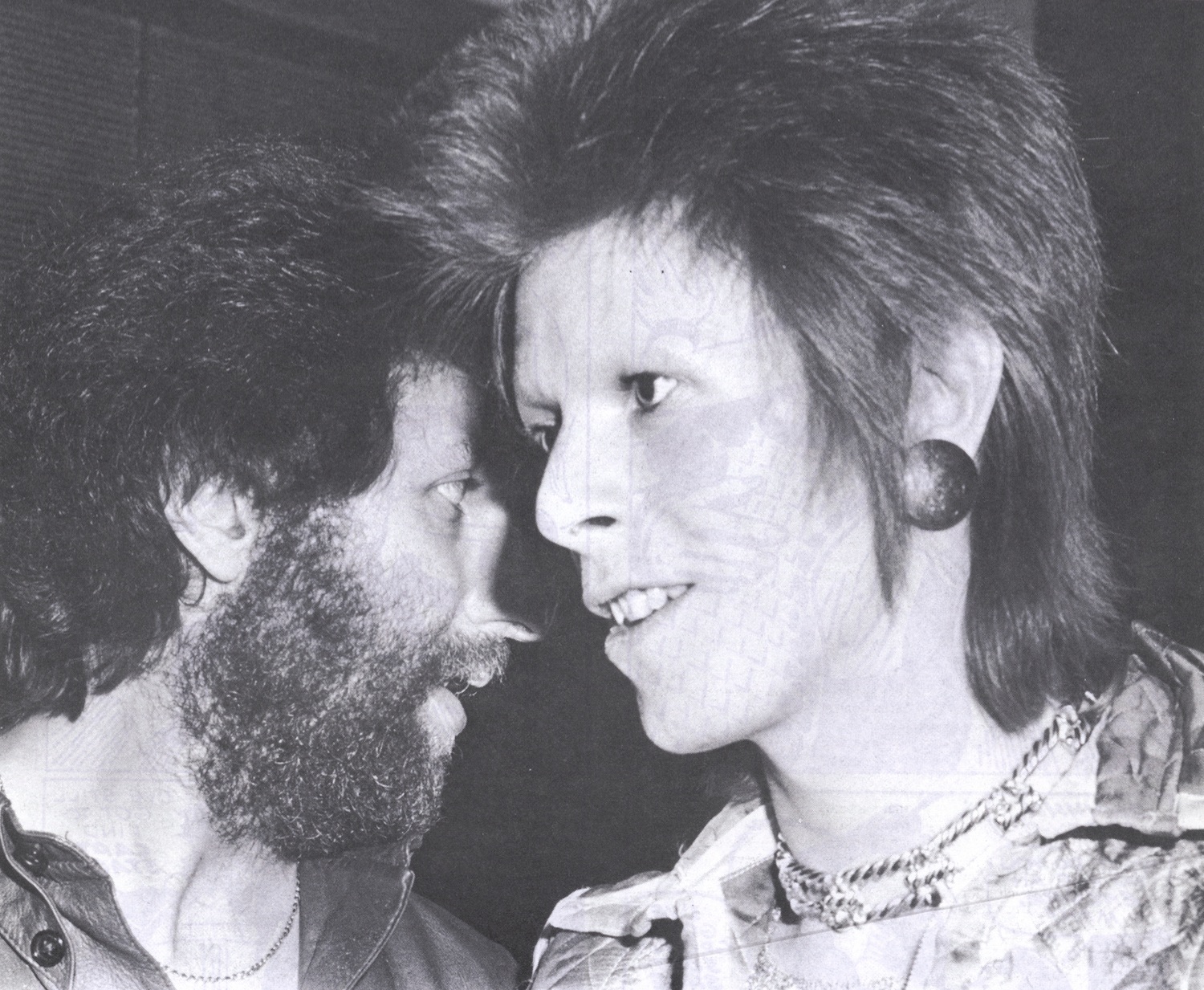

New Again: David Bowie

Forty years ago today, RCA Victor released The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars, David Bowie’s fifth studio album. The seminal concept album and impetus behind one of Bowie’s most exotic and taboo-shattering onstage personae endures, continually ranking highly on various “Best Album” lists and serving as perhaps the most revered contribution of the glam rock era. In honor of its anniversary, EMI is issuing a remastered edition of the album in both 180-gram vinyl and CD formats. The vinyl version is accompanied by an audio DVD, which includes previously unreleased mixes of select tracks, such as “The Supermen,” “Velvet Goldmine,” and an instrumental version of “Moonage Daydream.”

Interview has spoken with David Bowie often over the years, but the first time was in our March 1973 issue. Post-Ziggy, pre-Aladdin Sane, and years before a crippling cocaine addiction, The Berlin Trilogy, Labyrinth, and Iman, the newly critically successful Bowie sat down with music writer Patrick Salvo to discuss music as media, English versus American sensibilities, his intimate relationship with mental illness, and the precarious mechanics of social revolution.

DAVID BOWIE tells all and more to Patrick Salvo

By Patrick Salvo

PATRICK SALVO: You were born in Brixton, how far were you from Her Majesty’s Prison?

DAVID BOWIE: About 700 yards.

SALVO: You had a good view then.

BOWIE: They had a good view of me as well.

SALVO: What does imprisonment mean to you?

BOWIE: I think I’ve been in prison for the last 24 years. I think coming to America has opened one door.

SALVO: Do you ever get imprisoned by your writings?

BOWIE: No—I never get trapped by them. I lose them. They divorce me. Once I’ve written something it does tend to run away from me. I don’t seem to have any part of it—it’s no longer my piece of writing.

SALVO: Do you write to gain or lose your identity?

BOWIE: Possibly to understand it. I don’t think either to lose or gain.

SALVO: It seems as even you once said, “You say most things the long way ‘round.”

BOWIE: I do tend to. I’m not very articulate.

SALVO: Your songs tingle of extreme difficulties and social diseases, yet is there any definite solution to these problems in your works?

BOWIE: I suppose it stems from a non-understanding of the problems I was faced with. I used parody as a form of defense. Most people attack it that way.

SALVO: Can you give us some background?

BOWIE: Sure. I was born in London 1947, after the war. A real wartime baby. I went to school in Brixton and then I moved up to Yorkshire, which is in the north of England. I lived on the farms up there. So I’ve seen pretty well the best of both from the terrible slum area of Brixton, with a pretty heavy black population, to right up in the country on the farms. I’ve been a child through both so that both halves of it really influenced me and produced a schizoid attitude in life. I think that’s what confused me, because having seen the best of both I couldn’t cope with a lot of problems that were around. Now that I’ve come to America a lot of those problems have become very graphic. In fact, I just called up my wife and told her that I’d like to settle here for a year or two. A lot of things have opened up in the last three days. It’s really changed me around, it really has. There’s a lot of fabulous people here. Their views are so heavy, so pointed that it becomes very well analysed, what is going on in this country. My country is in the depths of lethargy and very apathetic, there is very little happening. There’s no action in my country. This is quite a challenge to come over to a country like this where for me the most important thing to me is that the music is a communicative blanket media. Where at home it’s merely something to listen to.

SALVO: It’s a way of life here for people where in Great Britain it’s more or less taken for granted.

BOWIE: Very much so. It’s nice, so it sells well, the people enjoy it purely as music. Over here…

SALVO: It’s almost like a religion.

BOWIE: No, I wouldn’t say that. I’d say it’s the most honest media that you have over here. Whether it’s a bit late because of the process of making a record and reproducing it. Whether it’s late or not doesn’t matter because it’s honest and anything honest when it comes out means something.

SALVO: What do you think of the media in Great Britain?

BOWIE: I think it’s better than yours, I think better use is made of it, although it’s terribly biased to the left.

SALVO: How about your radio format?

BOWIE: Radio in England is nonexistent. It’s very bad English use of a media system, typically English use.

SALVO: Even people who do get a chance to play some decent music only have limited air time. For instance John Peel.

BOWIE: There’s the John Peel Show and there is Sound of the Seventies and that’s it. I also believe there’s a concert now—a live concert for an hour. But there’s a good television programme called “Disco 2.” It’s quite good but again it’s average, average. It’s all on a down play. You know we’ve got this thing in England to be hip is to speak very down—like John Peel. And that just about sums up England. They don’t realize when they talk like that, then that is what they represent—absolutely. John underplaying everything like vodka. Totally kind of frustrating within himself I suppose.

SALVO: He’s doing an awful lot but he’s doing nothing.

BOWIE: Yeah—promoting a non-image.

SALVO: Are you content existing in the form of a human—it seems like you’re down on most of the human race but you’re rather personal in your writings.

BOWIE: Especially now, especially now this is true you don’t know how important this trip has been, I just did Europe but the climate in Europe is completely divorced from what’s happening over here. It’s a different world. Everything is in a different perspective now. Absolutely.

SALVO: I remember you saying once that you’ve already have most of the experience that you’re likely to go through in the next 40 years.

BOWIE: I feel so—I feel so.

SALVO: You were through the experiences perhaps but…

BOWIE: Yeah—I went through a lot of experiences. I’ve been through a lot as a boy, as a teenager and I’m still going through them now and there is no stop.

SALVO: This “growing up before one’s time” can at times lead to any amount of various functional disorders.

BOWIE: Yes, it does do.

SALVO: This is found quite plainly in some of your writings.

BOWIE: Yes, you’re right. It happened to my brother. Do you know the new album?

SALVO: The Man Who Sold The World.

BOWIE: There’s a track on that based on my brother, called “All The Madmen.”

SALVO: I heard he was in the hospital.

BOWIE: Yeah—in fact I just phoned up my wife and it seems he’s staying with us now. She wouldn’t tell me on the phone because he was in the room. I’m not sure whether he kinda ran away or what. He’s only 28, maybe 30. But, I mean there’s a schizoid streak within the family anyway so I dare say that I’m affected by that. The majority of the people in my family have been in some kind of mental institution, as for my brother he doesn’t want to leave. He likes it very much. He’s just been changed to a new one, but the old one, “Cain Hill,” he really dug. He’d be happy to spend the rest of his life there—mainly because most of the people are on the same wavelength as him. And he’s not a freak, he’s a very straight person.

SALVO: Did he walk in on his own two feet?

BOWIE: My mother signed him in, which is very sad, but she’s been in as well. She thought it did her good but it didn’t. We had to take her on holiday, we put her out in Cyprus for a bit. It’s getting very starchy. Ah! The time element you were speaking of. Listen, I want to lay a concept on you. Do you know a guy by the name of George Meyer, he runs the “Walrus.” He’s just read the Marshall McLuhan book CLICHE ARCHETYPE, he tried to explain it to me the best way he could and this is where I lost my mind, whatever the present pop art form may be, it is already clichéd. It’s typesetted whether it’s put down by the critics and artists as being superfurious non-being, for example Charlie Chaplin, Buster Keaton films, those people. At the time they were written in the morning, shot in the evening and they’d make a lot of bread and everybody though they were quite funny right? Now Charlie Chaplin had an academic following and he is now a genius. The rock & rock revival, the same thing. They’ve brought it out now and dusted it off, beautified example, Creedence Clearwater.

SALVO: What rock & roll revival?

BOWIE: Just the general feeling that rock & roll is/was good. All of it you know—like anything, they’d take out some trite and play it. At the time you thought it was a novelty record. After two plays you got good and fed up with it. And now they play it and it’s marveled as spectacular, really great.

SALVO: Because of the nostalgia involved.

BOWIE: And the ’30s and ’40s and so on. Now here’s the crunch. So an astronaut goes to moon, takes a photograph of the earth, comes back and sets up an Archetypal Earth which is not longer useful. It’s now in the past. People are cleaning it up—ecology and so on. So where are we now? What’s the next step after that one? Boy that’s a heavy theory. Nobody in England would get that—I mean it doesn’t mean anything up there. They’re still convinced that there’s a revolution. They’re so disillusioned. That’s why I haven’t been getting into it anymore. I have to stay with my own circle of friends, my wife…

SALVO: Are most of your friends artists, performers and the like?

BOWIE: No musical friends except Marc Bolan from T-Rex is the only friend I have in the business. Do you have Jehovah Witnesses over here?

SALVO: Sure, they used to visit my mother quite often but I think she was putting them all on. They wouldn’t say no, but she wouldn’t say no either so it was a gas. As for yourself, you obviously don’t believe in organized religion but you were once a Buddhist. You practiced it and that would be organized to an extent.

BOWIE: Well that’s why I’m not a Buddhist anymore. I wrote a song called “The Supermen” which was about the Homo Superior race and through that I got interest in Nazism. I’m overwhelmed at their methods—diabolical. I have no room in my head to entertain their theory, the gross effects, the terrible disregard for human life, especially for particular races and religions. You knew Roman Catholics were next. The Pope bought Hitler off. It was the whole thing about the Magic Wine. Hitler wanted to develop an Aryan race. For what reason? To fight Homo Superior. He was dreadfully afraid of Homo Superior and his aims to develop a race of Aryan people was a misrepresentation of that good feeling of Homo Superior. Because if it was such a depressed era, spiritually and morally that it came out all wrong. I’m sure Hitler could have gone the other way. But mind you this is a mad planet, it’s doomed to madness. We might have freaked the world so much, twisted it off its axis, its practical and mental axis so much that the way these new children could be influenced by their grandparents might have ticked something off in their head that you may well find that we have given birth to Homo Superior prematurely.

SALVO: In another one your songs, “Cygnet Committee,” you get totally involved in the so-called militant hippie movement.

BOWIE: Wow—why did you pick that one? That’s crazy, nobody picks that one, they get hung up on “Memory of a Free Festival,” “Space Oddity,” and that’s it. Maybe “Janine,” but this is remarkable.

SALVO: It’s rather long and involved and it is in segments isn’t it?

BOWIE: I basically wanted to be a cry to fucking humanity. The beginning of the song when I first started it was saying—Fellow man I do love you—I love humanity, I adore it, it’s sensational sensuous, exciting—it sparkled and it’s also pathetic at the same time. And it was a cry to list O.K., that was the first section. And then I tried to get into the dialogue between two kinds of forces. First the sponsor of the revolution, the quasi-capitalist who believes that he is left wing and put support into a lot of the pure, what ended up being what I anticipated that particular movement for quite a few months over in England. People like Mick Farren, Jerry Rubin, etc.

SALVO: Mick Farren, formerly a deviant and a Pink Fairy, now leader of the British White Panthers.

BOWIE: And that’s what I saw coming up.

SALVO: Do you think they had a valid thing?

BOWIE: Rubin, no not at all, it’s set up so many false values, so many bad standards such intolerance and hypocrisy. I mean the truest form of any form of revolutionary left, whatever you want to call it was Jack Kerouac, E.E. Cummings, & Ginsberg’s period. Excuse me, but that’s where it was at. The hippies, I’m afraid, don’t know what’s happening. I don’t think there are any anyway. The underground really went underground. Grand Funk, and all these people man are the moderate’s choice of music. Underground is Yoko Ono, The Black Poets. These people scare the hell out of most freaks. They laugh at Yoko Ono, but it’s the whole cliché.

SALVO: It’s like when Lennon makes a movie and everybody is told to disrobe, the cat who runs around fully clothes is the most obscene.

BOWIE: Right, John Lennon comes in the same period. He was into Ginsberg before he was into anything else.

SALVO: So do you think there really is or was a movement?

BOWIE: There was a movement but the revolution has been fought on an entirely different plane to the plane that I thought it should be fought on. It was intrinsically bad. Every time there was something to say for any and every form of people’s society. For instance, like capitalism can be all right, I mean Marx didn’t live to see what Roosevelt did with that depression. He pulled everybody out of that depressed and everybody hated Roosevelt. He got into office four times. One after the other, with everybody saying, he can’t get in again. Everybody voted for Roosevelt four times and he did a hell of a lot. Mind you I’m a little political, not too much but I’m branching off very much here. You see I’m just getting quick flashes of what I think.

SALVO: Then it goes on: “Infiltrated business cesspools/Hating through out sleeves,/Yea, and we slit the Catholic throat/ ‘Wish You Could Hear’/ ‘Love Is All We Need’/ ‘Kick Out The James’/ ‘Kick Out Your Mother’/ ‘Cut Up Your Friend’/ ‘Screw Up Your Brother or He’ll Get You In The End.'”

BOWIE: Sure, all the clichés, passé stuff—again, parody.

SALVO: At the very finale you state that you want to believe. At time this is quite difficult, but exactly in what do you want to believe in?

BOWIE: I would like to believe that people knew what they were fighting for and why they wanted a revolution, and exactly what it was within that they didn’t like. I mean, to put down a society of the aims of a society is to put down a hell of a lot of people and that scares me that there should be such a division where one set of people are saying that another set should be killed. You know you can’t put down anybody. You can just try and understand. The emphasis shouldn’t be on revolution, it should be on communication. Because it’s just going to get more uptight. The more the revolution goes on, and there will be a civil war sooner or later.

SALVO: Over here there’s one every summer. Finally, would you care to elaborate on the state of the English youth today?

BOWIE: I wouldn’t care to.

SALVO: It’s that bad?

BOWIE: It’s not that bad, but it’s so crazy.

SALVO: Do you think it will come together in the end, will they suss it out somehow?

BOWIE: I don’t think there’s any chance of sussing it out. I think there will be a period where man will be fairly content. More content than he’s been for some time. Since early middle ages when people generally taking away the barbarity of their like, were pretty content. Although it was all an illicit contentment, what with the slave systems all over the world, in England especially, the peasants and the master, etc. People were incredibly content. There will be another age of contentment. I don’t know how long.

SALVO: This is the age of apathy in Great Britain mainly because they really don’t have much to commit themselves to. It would be different if England were totally involved in a war…

BOWIE: Exactly, exactly they want to be Americanized, a lot of them are hippies and they’re so shook up man ‘cause they’ve got nothing to fight and that makes them so frustrated.

SALVO: They’re given the vote and 18 you know, sign contracts—big deal.

BOWIE: There’s nothing to vote for anyway and nothing’s really bad enough to bother to replace it, ‘cause you can get through.

SALVO: They’re frustrated because they really don’t have a valid grievance to revolt against but they all got two legs.

BOWIE: That’s why they switch from one subject to another in England all the time. One moment it’s Black Power, the next moment it’s the war in Vietnam—anything just to grab onto until it gets a bit boring because nothing actually happens. It’s like THIS SKETCH IS A BIT SILLY, LET’S GO ON TO THE NEXT ONE.

THIS INTERVIEW ORIGINALLY APPEARED IN THE MARCH 1973 ISSUE OF INTERVIEW.

For more New Again click here.