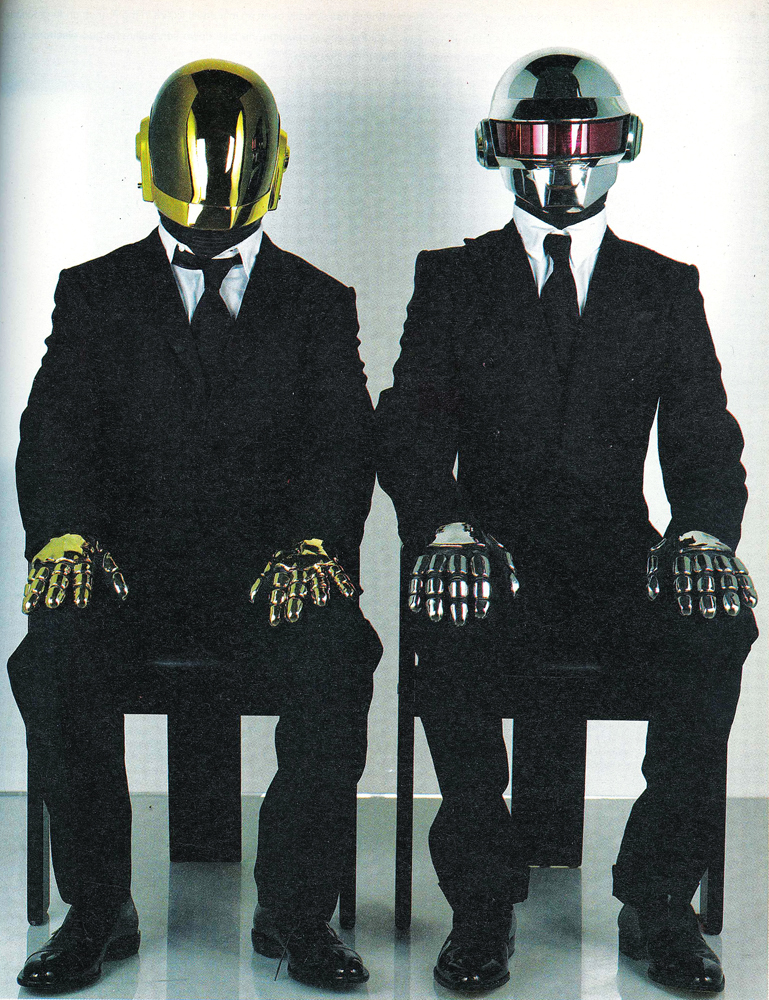

New Again: Daft Punk

Daft Punk, one of electronic music’s most popular duos, is going harder, better, faster, and stronger. With a pop-up shop like no other opening up in L.A.—a Daft Punk fan’s dream, reports Pitchfork—and a highly-anticipated Grammy performance alongside the Weeknd, this French pair are in for quite the month.

The pop-up shop will not only feature Daft Punk merchandise that has previously only been available through their online shop, but several designers including Gosha Rubchinskiy and Hervet Manufacturier have created special apparel and accessories for the event. If you’re in L.A. between Feb 11 and 19, stop by 8818 Melrose Ave. in West Hollywood to buy up all the “archival set pieces, props, wardrobe, artwork, photography, and robot helmets” you can get your hands on.

Before you binge listen to their vast discography, read through this interview they did in 2001 about their music influences, the politics of electronic music, and their worldly patriotism.—Katrina Alonso

Daft Punk

By Dimitri Ehrlich

DIMITRI EHRLICH: In the early ’60s, the Rolling Stones reinterpreted music from Chicago, blues people like Howlin’ Wolf and Muddy Waters, and became much bigger among American teenagers than the actual American blues musicians they borrowed from. In the same way, you guys have taken techno music from Detroit and house music from Chicago, reinterpreted it, and now Daft Punk is probably more famous among American teenagers than any of your American influences.

GUY-MANUEL DE HOMEM-CHRISTO: Yeah, maybe it’s like that. Your comparison is funny. It’s true that when I was younger and I first got interested in music, I used to read books about the Stones and the Beatles and how they listened to Muddy Waters and people like that when they were starting out, who are much less well known now than the Rolling Stones. The Stones really changed blues. But I don’t really know if it’s about our music being different than the original Chicago house music makers from the ’80s. I think it’s more about timing, maybe.

EHRLICH: Would Daft Punk’s music have been different if you’d grown up in Chicago or New York?

THOMAS BANGALTER: It would have been really different if we hadn’t listened to music from Chicago or New York. We incorporate a lot of American and English-based influences, but take them completely out of context. The way we listen to Chicago house music, disco, heavy metal or punk is completely artistic, without the political side of it. But then we used it in a political way ourselves, which is making music at home, recycling and by combining those styles at home and doing it in a very new way.

EHRLICH: How is making music at home political?

BANGALTER: Everybody does it now, but Homework was completely done in a very small bedroom. It’s mixed on a small ghetto blaster. Selling millions of albums recorded that way is something new. I don’t know if it’s political, but it’s a way of thinking that record companies aren’t always going to dictate to artists. It’s like The Blair Witch Project [1999]. You might not have thought it was political when it was done, but it broke the whole system because you had three kids making a video with a camcorder that infiltrated multiplexes.

EHRLICK: For a long time there was a cliché of techno music as being faceless, and then you guys came along and literally covered your faces. Why?

DE HOMEM-CHRISTO: We wanted to draw a line between public life and private life. We didn’t understand why it should be obligatory to be on the covers of magazines as yourself when you are making music and are not a showman.

EHRLICH: You’ve always been as concerned with the visual as with the sonic aspect of music. How would you describe your aesthetic?

DE HOMEM-CHRISTO: Music is the core of what we are trying to do, and we try to find many other ideas around it.

BANGALTER: We’re having a lot of fun discovering it from the inside. It’s like pop art, for example; when you look at Andy Warhol, he was producing movies and making art and producing stuff like the Velvet Underground—he took a whole global imagery approach.

EHRLICH: Do you feel any particular pride about being from France?

BANGALTER: No, it’s not part of our world. America is a new country, and maybe patriotism helps Americans create unity, since it is a melting pot. But nationalism in Europe has a strong history, as you may know.

EHRLICH: Yes, I’ve heard. I believe there was something called World War One.

BANGALTER: Yes, and also World War Two. So being nationalistic in France has nothing in common with being patriotic in America. We are definitely pro-European, even pro-global, and house music and electronic music has developed a network all over the world, between record shops in Berlin, Tokyo, London, Chicago, Minneapolis and L.A. That’s really what we feel part of, rather than being French.

THIS INTERVIEW ORIGINALLY APPEARED IN THE OCTOBER 2001 ISSUE OF INTERVIEW.

For more from our archives, click here.