New Again: Chrissie Hynde

It’s been nearly four decades since Chrissie Hynde formed the Pretenders in 1978, but this month, the seminal rock band is still making news: Their latest record, Alone (BMG), was released last week and yesterday, the group played the first show of their North American tour with Stevie Nicks. While Chrissie Hynde is the only original band member to appear on the new record, she enlisted talented collaborators such as the Black Keys‘ Dan Auerbach on the LP’s production.

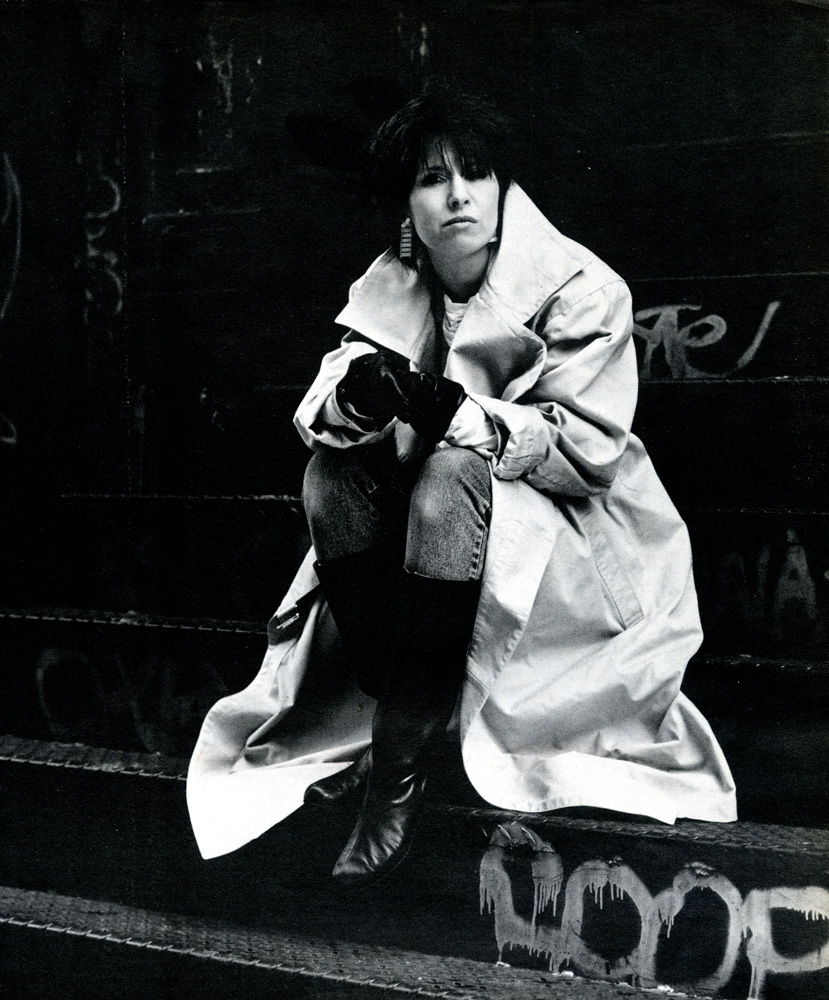

In honor of the new Pretenders tour and record release, we’re revisiting a conversation with Chrissie Hynde from the April 1986 issue of Interview. At the time, the band’s founder, lead singer, and guitarist was in the process of recording that year’s release, Get Close. Hynde told us about her changing hometown of Akron, Ohio, being famous with two children, and what she thought about pop superstar Madonna. —Natalia Barr

Chrissie Hynde

By Lisa Robinson

Pretenders’ founder, lead singer, and guitarist Chrissie Hynde would probably, given her modesty, be the last to admit it, but she is considered one of the premier songwriters in rock ‘n’ roll. She also has one of those rare voices that makes you stop and say, “Who’s that?” (as I did six years ago when I heard “Brass in Pocket“) when you first hear it on the radio.

Far removed from her false, early image as some black-leather-clad bitch goddess, Chrissie is one of the most solid, down-to-earth, thoughtful people in the music world. She’s had her share of highs and lows: Following the success of the first two Pretenders’ LPs, two of her closest friends, band members Pete Farndon and James Honeyman-Scott, died of overdoses within one year of each other. Chrissie put together a new Pretenders lineup (Hynde, original drummer Martin Chambers, new bassist Malcolm Foster and guitarist Robbie McIntosh), released an LP, Learning to Crawl, and has now, three years later, begun another with producers Jimmy Iovine and Bob Clearmountain.

During the time that all of the above was taking place, Chrissie had one daughter, Natalie, with Ray Davies, with whom she had been involved, and then married Simple Minds’ leader Jim Kerr, with whom she has a daughter, Yasmin. Chrissie remains positive about the future, despite her “soap opera” life the past few years, but, as she says, “The down side of all that is that I can’t get fulfilled watching Dynasty with everyone else.”

LISA ROBINSON: There seems to be more babies on rock tours these days than groupies. That certainly is the case with the Pretenders, isn’t it?

CHRISSIE HYNDE: There’s no groupies, but there never were a whole lot of groupies hanging on, anyway.

ROBINSON: Not even in the very beginning?

HYNDE: Well, the guys that the groupies came around for died off so early…

ROBINSON: Did you ever have boys coming around, trying to pick you up?

HYNDE: Never.

ROBINSON: Why not? You always used to hear these stories about Janis Joplin sending roadies into the audience to find cute boys.

HYNDE: She was still going through her experimental days, you see, when she was in a band.

ROBINSON: You’d already done it?

HYNDE: I’m not saying I’d already done anything, actually, Lisa, but I’d passed my experimental streak. Plus, the thing is, when you’re in a band and you’re a girl, you know, guys just don’t … it’s not the same kind of a groove as a girl walking up wearing a mac with nothing on underneath, or knocking on someone’s door at three in the morning.

ROBINSON: Are you very aware these days of having mellowed, or wanting to be more dignified?

HYNDE: It’s just being older. I’m very aware of that. But just in sort of a natural way. You know, when you’re 23 and you get pissed, I mean drunk, you can just go crazy and it’s all right. But if you’re 43 and you do it, it’s like your best friend’s mother who used to come in pissed and everybody was really embarrassed. It just doesn’t go down well, you know, after a certain age.

ROBINSON: Pat Benatar keeps using you as the example of someone who can still go out on a rock tour and take her child, which is what she’s determined to do.

HYNDE: Well, I took the one girl around for nine months on tour, but now with two of them, I think I’ll change things a little bit. First of all, they don’t want to be disrupted and dragged all over the place when they’re going to play schools with their friends and they have their own little world. I’ll just have to keep it to a minimum, a couple of months at a time, or something like that. I’ll work it out. I don’t want to do it that much anyway. You know, in this business, things go in waves, and I might make a record every three years. That’s enough for me, that satisfies me. And it satisfies the so-called public, because they don’t really need a record every year. They don’t even want one. There’s other stuff out there for them to listen to.

ROBINSON: But do you think there’s a lot of good stuff out there? Do you harbor much hope for rock ‘n’ roll?

HYNDE: I think it’s a whole different thing now. Instead of being a sort of youth culture and a youth music, it’s become more contemporary music. Which is all right. But when you and I started getting interested in rock ‘n’ roll, it was because there was one guy on the street and he was the one who had a motorbike and he had a couple of rock ‘n’ roll records. We still associated this with a sort of antiestablishment renegade kind of thing. But now, it’s a lucrative career. I mean, I got into a band because I didn’t want a career. But now, all of a sudden, being in a band is this fabulous career, you know?

ROBINSON: You said to me once that parents used to be horrified if their kid wanted to be in a band; now they give them synthesizers for 16th birthday presents.

HYNDE: For my 21st birthday, I think my mother wanted to give me a watch, or something, you know, some kind of traditional thing. And I said, “Well, if you’re going to buy me something, there’s a Gibson Melody Maker guitar advertised in the paper for 60 dollars. Do you think I could have that?” And I think that she was very disappointed that at 21 I was still messing around with that sort of thing. She didn’t understand what it was all about. But now she understands it, and likes it.

Music reflects the time that it’s being made in, and so certainly, the music that’s being made in 1986 by a 14-year-old kid will reflect some magic of 1986 for him if he’s an inspired and creative musician. I mean the cliché of that sort of wasted, renegade, drugged-out musician of the ‘70s is kind of dead and gone now. And I suppose that a lot of people still keep relying on that, or some kind of image to perpetuate something that they think they’re supposed to sound like. But that kind of takes you away from real inspiration and, you know, real artistic discovery of the individual. When I was 16, the pot weeded out the men from the boys, there were the heads and the straights. Now it’s almost like money can weed it out, you know? The people who are making a lot of money and eating at McDonald’s and watching MTV and have square eyeballs, they’re over there. And then maybe there’s like five other people left in America and I’m just waiting for them to come up with something interesting.

ROBINSON: Where do you fit in all of this?

HYNDE: Oh, I just ramble along and make a record once in a while.

ROBINSON: But there still is an edge to what you do, don’t you think?

HYNDE: I hope there is an edge to what I do. I think if I lost an edge, or the music didn’t have the aggression or whatever, which is maybe one of the hallmarks of what I do, if indeed it is, I still think if you have something original in what you do and you keep doing that, then you’re all right. If you’re purely derivative in what you do, then you could very easily get lost along the way. But for me, I might want to even do something else for a while.

ROBINSON: Like what?

HYNDE: Oh, you know, have babies, things like that.

ROBINSON: More?

HYNDE: Or whatever, I don’t know. Paint or travel or just do something else. I don’t like to think that I’m on a treadmill of album, tour, promotion and all that.

ROBINSON: You still don’t think about doing movies?

HYNDE: I haven’t really. I mean it does occur to me, because other people I know do films.

ROBINSON: Who do you think does it well?

HYNDE: I don’t know if anybody does it well. I think good actors and actresses do it well.

ROBINSON: But nobody in music? Sting? Bowie? Madonna?

HYNDE: I haven’t seen their films.

ROBINSON: What do you think about Madonna?

HYNDE: I like Madonna a lot. I think she’s really good and I think she’s a good singer. I think she looks good and she’s got a nice kind of… I don’t think she’s got a sinister or cynical vibe around her, and I don’t think she’s got any sort of bullshit around her. And I don’t think it’s particularly playing on eroticism. I think it’s really good pop music and I for one, if I were sitting on the steps of a tenement building and I was 14 years old and didn’t think the future had any prospects for me, I’d much rather listen to her than some sort of social conscious music talking about the red wedge or, in England, Paul Weller talking about voting socialist.

ROBINSON: Have you been back to Akron at all?

HYNDE: Not very much. Because my family moved away. It’s changed a lot there now. People moved away, and visually it’s different. The beauty spots, well, to my mind, what the beauty spots were, there’s all parking lots and things now.

ROBINSON: So it really is like your song, “My City Was Gone.”

HYNDE: Oh yeah. Like most of America.

ROBINSON: I think New York City is like that now.

HYNDE: I was shocked. I was at a coffee shop across the street from the Berkshire Place Hotel and I was talking to someone in there and I said, “There must be a thousand, tens of thousands of coffee shops like this in New York.” I was thinking we were in this typical New York City diner, and she looked at me and said, “This is one of the few that are left.” I was really shocked.

ROBINSON: There is a certain image that comes across in the press of you sometimes as being difficult, and a terror…

HYNDE: Well, I don’t wish to embarrass anyone. Maybe they just ask me dumb questions. I expect people to at least use some thought. Not because I’m something special, but look, I’ll tell you what it comes down to. I’m not a complete moron like most musicians whom I’ve met. I’ve only in the past few years realized that they are thick as shit. You know, I always thought if a guy could play the guitar, he must be something really special.

ROBINSON: I know, why do we think that? It’s like if someone has this wonderful voice, therefore, he must be a wonderful person.

HYNDE: Because we’re hypnotized. Because we love it. It’s like they give us a lot of pleasure, and they might be very inspired. But only recently have I realized that you shouldn’t necessarily expect to get much more than that out of them. See, there’s this celebrity thing that goes along with making records or being a rock star. I’m into this celebrity thing just enough to let me go on making records and making a living out of it. I don’t like to push it past that point because I don’t like to be recognized on the street or in restaurants, and I don’t like the whole celebrity thing. I don’t really go out to clubs, but if I did, I’d just want to go rock out with my mates or whatever. I’ve never been to a Hollywood party, although I imagine that it might be fun. But I’d really rather just be the anonymous Mr. Nobody who I always was up until I first went onstage. I liked that.

ROBINSON: You never wanted to be famous?

HYNDE: Oh, when I started it was just to be in a band. The whole fame thing was so different, you know? Now there’s People magazine, and the celebrity thing is such a thing in itself now. Then, everybody wanted to be the Beatles or the Rolling Stones because they just had the coolest clothes and they made those brilliant songs and everything. And we all had that element of hero worship.

ROBINSON: But when you were a fan, didn’t you want to know all about their personal lives? Who their girlfriends were…

HYNDE: Oh, I wanted to know everything. What they had for breakfast, everything.

ROBINSON: So do you understand why people are interested in that?

HYNDE: Oh, I totally understand it. Totally understand it.

ROBINSON: But you don’t want to give them that about yourself.

HYNDE: Because I want the freedom to just be one of them.

ROBINSON: You are very private about your private life…

HYNDE: I don’t want my children to be at a disadvantage, growing up in the limelight, because then they have to live up to an identity already cut out for them, relating all the time to being so-and-so’s daughter or so-and-so’s son. I had a very colorless background, and when I left Ohio and moved to England, nobody knew who I was and I had a real freedom. I could be free to experiment and experience things and I liked that a lot.

ROBINSON: How can that be possible for your children? You have two children so far, both of whom have well-known fathers, you’re well known, and they’re not going to be able to completely get away from that.

HYNDE: Well, I think I can work it out all right. I’m 34 now, I like to say 35 because it makes me look better for my age, and I have to keep a little bit of a profile so that every three years if I do put a record out, I don’t have to substantiate where I’ve been for three years and why the silence and the sort of false mysterioso. I just want to be as regular, and get by with doing the least amount of publicity, but still look really cool, you know? And get a bit of respect.

ROBINSON: Another thing, with all of the problems you had with the guys in the band dying, and a variety of stormy relationships and your marriage, all that you’ve been through, you’ve always publicly acted as it it’s no big deal.

HYNDE: It’s so tame compared to me everyday … I mean, all you have to do is turn on the news and you see someone standing on a foot of the roof that’s all that’s left of their home, looking for their family who have all been killed in a volcanic eruption, or, you know, see people whose families have been devastated by earthquakes and things. I mean, I’m going to go out in the street now and get a cab and go on to the studio. What can be bad? How could you possibly say this is hard?

ROBINSON: But when you’re going through difficult times, it’s still the worst thing that’s happened to you at the moment…

HYNDE: Yeah, of course it is, but you know, everyone has their set of problems and I’m certainly not going to sensationalize mine or try to evoke pity or sympathy out of people because I don’t think they warrant that sort of thing. That’s my private karma that I have to work out. It’s my tough luck if things happen that are complicated.

ROBINSON: You said you’ve been staying home a lot. Do you cook?

HYNDE: Not very well. And I can only cook brown rice and vegetables, so I don’t get too many people coming over for dinner parties or anything. I don’t listen to music, and I don’t particularly watch television, so if anyone wants to come over and just hang out with me sitting at the table in silence, you know, eating a dish of rice… I don’t get too many takers. In fact, I’ve only been to a couple of other people’s dinner parties. But I must admit, I really enjoyed the few I’ve been to, but I’m not really on that circuit either.

ROBINSON: It beats hanging out in a club.

HYNDE: Well you know, once you stop drinking and smoking and stuff, it really gets on your nerves, all that nonsense going on. And you have conversations with people and you spend three minutes explaining something and they look back and they go, “What was the name of that film?” And you just say, “Well, I’ve got to go.”

ROBINSON: You do feel that you’re in a very good relationship with Jim now, don’t you?

HYNDE: Well, I’m with someone who’s got very high standards, and he doesn’t tolerate all these ridiculous vices very easily. That’s not reason enough to marry someone, although people have gotten married for less. Let’s face it, we do have this mating instinct that just won’t quit, you know? Just when you think it’s safe to come out, there it is again. You’re driving down the street, and it’s the last thing on your mind, and all of a sudden you’re like, “Oh, he looks nice,” and you’re up a lamppost.

ROBINSON: You don’t have any problems with competition with him? With both of you being in the same “business,” you know how sometimes there are some guys who wouldn’t want their wife of girlfriend to be more successful than they are…

HYNDE: I’ve noticed. But then, you just have to get away from those guys. It’s not even really a matter of the male/female thing, although I know exactly what you’re talking about. But you have to get away from that on a personal dignity level, and realize your own potential and try to live out your expectations of your potential. But real success is not being on the cover of a magazine; it’s knowing that you’ve done, and enjoyed doing, what you set out to do.

ROBINSON: You and Jim never even slightly look at the charts and see whose record is going better … I’ve known couples in this business where that is really a problem.

HYNDE: I know exactly what you’re talking about. It’s a very, very common thing. Fortunately, with Jim, he would be delighted if I do well at something. In fact, he’s very disappointed if I don’t go for it and really try to do as good a job as I can and really try to do as good a job as I can. He’s the most encouraging person and he really helps me and gives me good advice. Totally sort of unbiased and unemotional. He’s a great aid to me in that respect.

ROBINSON: Do you really not think that you’re a good songwriter?

HYNDE: I’m not going to judge what I do. I think Bob Dylan’s a good songwriter. I think he’s the best songwriter in the world probably.

ROBINSON: Jimmy Iovine thinks you, Bruce Springsteen, Tom Petty, Bono, Jim … are the best songwriters.

HYNDE: Well, I don’t know. I know he does know some great pizza houses.

THIS INTERVIEW ORIGINALLY APPEARED IN THE APRIL 1986 ISSUE OF INTERVIEW.