New Again: Brian Eno

Last week experimental artist and pop pioneer Brian Eno announced that come the first day of 2017, he will release Reflection (Warp), a new album of ambient recordings. It’s the latest in a musical lineage dating back to 1975’s Discreet Music, Eno’s first major leap into ambient sounds, which arguably put the genre on the map. Eno, who has always emphasized the theoretical processes behind the creation of his music, calls Reflection a collection of “generative” pieces in that “they make themselves.” He further explains, “It seems to create a psychological space that encourages internal conversation. And external ones, actually—people seem to enjoy it as the background to their conversations.”

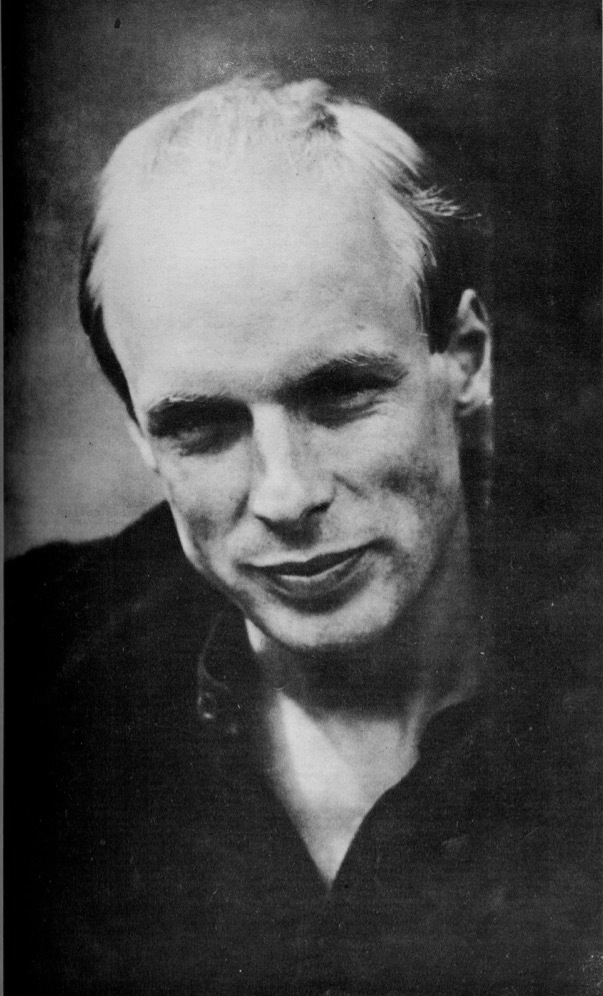

In anticipation of Reflection‘s release, we’re reprinting Eno’s feature in the June 1978 issue of Interview. Conducted post-Roxy Music and during his collaborative years with the Talking Heads, it sees Eno’s solo work in the nascent genre of electronic music having quickly established him as an enigmatic innovator at the forefront of pop’s avant-garde. In this interview, he focuses on how his music comes about by discussing his complex methodologies, the studio technology of the day, and the formation of the practical creative lifeline Oblique Strategies. —Frank Chlumsky

Eno at the Edge of Rock

By Glenn O’Brien

Brian Eno was a founding member of Roxy Music, the English band that more or less founded the Fine Art-Fashion-Rock and Roll fusion that continues to make the world a more interesting spot. And while Bryan Ferry was Roxy’s front man, Eno was the band’s focal point—supplying the most radical musical and visual input.

After a couple of historic Roxy albums, Eno left the band to pursue his own directions, which proved to be more radical, innovative, and eventually, successful than Roxy. He has made four avant-pop solo albums: Here Come The Warm Jets (1973); Taking Tiger Mountain (By Strategy) (1974); Another Green World (1975); and Before and After Science (1977). None of these has been a major chart hit, but all of them have aged well, sounding as fresh and revolutionary today as when they were made, and selling even better. More than any other pop artist, Eno has bridged the gap between “serious music,” the techno-avant-garde and “fun music,” music that you can dance to.

The solo albums explore many forms, from hard rockers, to minimal mood pieces, to robot disco—but none of them are strictly definable, perhaps because they’ve been arrived at in strange ways. Among the instruments played by Eno on his solo albums are: snake guitar, piano, synthesizer, digital guitar, vibes, bells, castanet guitar, synthetic percussion, club guitar, uncertain piano, tapes, electric larynx, etc.

Eno has also collaborated on two albums with Robert Fripp, the former lead guitarist of King Crimson: No Pussyfooting (1973); and Evening Star (1976). He has performed live with various assemblages of musicians, resulting in two live LIPs, 801 Live (a Roxy spinoff with Phil Manzanera) and June 1, 1974 (with Kevin Ayers, John Cale, Nico et al.) He has produced one album of muzak for the bright, Discreet Music (1975).

Perhaps Eno’s funniest work is his production of The Portsmouth Sinfonia, a symphony orchestra composed largely of musicians who can’t play, but who make a fabulous try anyway on such numbers as “The William Tell Overture” and “Thus Spake Zarathustra.” But lately Eno’s come into great demand as a “serious” producer and he has worked with the English “new wave” group Ultravox, and most recently the Talking Heads, New York’s favorite “art band,” and Devo (the Devolution Band), a big favorite of David Bowie and Akron, Ohio.

And probably Brian Eno’s greatest “claim to fame” is his collaboration with David Bowie on the latter’s latter two platters, Low and “Heroes,” which have greatly extended the boundaries of pop music.

I began talking with Eno about Oblique Strategies, which is an “oracular” deck of cards he designed with artist Peter Schmidt for the purpose of solving problems in artistic processes.

GLENN O’BRIEN: How did you devise Oblique Strategies?

BRIAN ENO: They have quite a long history. When I was at art school I started making programs or devices to extricate myself from rapt situations while I was painting. You often find yourself in a situation where your focus on detail is so concentrated that your actual overview of the whole disappears and you’ve lost any possibility of stepping outside and seeing it as a complete thing. The idea of Oblique Strategies was just to dislocate my vision for a while. By means of performing a task that might seem absurd in relation to the picture, one can suddenly come at it from a tangent and possibly reassess it. So I had about five or six little principles that I carried in my head at that time. Then when Roxy started and we made our first album, although I liked the album a lot, as soon as we had finished it and I was in a position of sitting at home and listening to it as a record, I began thinking, “If only I’d done this or that.” I could suddenly see lots of places where a slightly more detached vision or a different angle of approach would have made a lot of difference. So the next time we recorded, I compiled a set of about twenty-five little cards, which I’d just stick around the studio and keep reminding myself of all the time. They were the kind of ideas that are in Oblique Strategies. Many of them still survive in the pack that is extant now. The kind of panic situation you get into in the studio is unreal. It doesn’t always profit the music. You’ve got until eight o’clock and you’ve got to get something finished. You tend to proceed in a very linear fashion. Now if that line isn’t going in the right direction, no matter how hard you work you’re not going to get anywhere. The function of the cards was to constantly question whether that direction was correct. To say, “How about going that way?” Since then each time I’ve gone into a recording studio I’ve found myself adding to them. I would later find other little principles that became useful.

Later I showed them to my friend Peter Schmidt, the painter, and he said, “Oh, I’ve been doing a similar thing.” And he showed me a notebook he had, which had on each page a comparable aphorism or idea. Many of the ones he had were identical to mine. So we complied them and then sat down and invented some more. We began to recognize that this could be a working proposition, and we finally published them in a very small edition.

They’re still useful. One would think that after a while their ability to disturb a procedure would pale, but it hasn’t happened to me. I’ve chucked a few out of the deck because they’re of no use anymore, but there are still about ninety I use.

O’BRIEN: Have you ever used the I Ching?

ENO: Yes, in fact it was about the time that I was getting interested in that that I also got interested in the Oblique Strategy idea. And of course, all of those oracles work in the same way. You can either believe that they carry intrinsic wisdom of some kind, or else you can believe that they work on a purely behavioral level, simply adjusting your perception at a point, or suggesting a different perception. Or you can believe a blend of both.

The Oblique Strategy was an attempt to make a set that was slightly more specific, tailored to a more particular situation than the I Ching, which is tailored to cosmic situations, though I suppose that with sufficient skill one could use the I Ching in the same way.

O’BRIEN: Do you pick cards at random, or do you look through the deck until you see one that strikes you as relevant to the situation?

ENO: I always pick at random. Other people sort through them, but I never use them unless I come to a point where a piece isn’t getting anywhere and needs help. When I work there are two distinct phases: the phase of pushing the work along, getting something to happen, where all the input comes from me, and phase two, where things start to combine in a way that wasn’t expected or predicted by what I supplied. Once phase two begins everything is okay, because then the work starts to dictate its own terms. It starts to get an identity which demands certain future moves. But during the first phase you often find that you come to a full stop. You don’t know what to supply. And it’s at that stage that I will pull one of the cards out.

Later on you might be faced with a number of options that seem equally desirable—again I might pull one out rather than try all the options. I’ve used them on nearly every record I’ve made.

O’BRIEN: Do you write methodically?

ENO: All kinds of different ways. I don’t have a technique, one way of working. I suppose broadly they fall into three or four categories. One is the traditional category—I have a tape recorder like yours [micro-cassette] and I always have it with me. I might be walking along and I’ll think of a rhythm or a melody or a series of words or some little idea that I’ll note on it. I have thousands of those notes, in fact. Then I’ll go through them all and see if any of them fit together. After that they go into a kind of demo stage and into my tape library where I attempt to keep them in some kind of order, which is very difficult because I don’t know what to call them or how to classify them.

Just as frequently, I go straight into the studio and see what’s around. I might hire a couple of instruments that I’ve never used—maybe a particular type of electronic organ or an echo unit. Then I just dabble with sounds until something starts to happen that suggests a texture. The texture suggests some kind of mood, and the mood suggests some kind of lyric. That’s like working in reverse, often quite the other way around, from sound to song. Although often they stop before they get to the song stage.

Another way of working is setting deliberate constraints that aren’t musical ones—like saying, “Well, this piece is going to be three minutes and nineteen seconds long and it’s going to have changes here, here and here, and there’s going to be a convolution of events here, and there’s going to be a very fast rhythm here with a very slow moving part over the top of it.” Those are the sort of visual ideas that I can draw out on graph paper. I’ve done a lot of film music this way.

Another way—I have to enumerate these, because I use them all about equally often—is to gather together a group of musicians who wouldn’t normally work together, perhaps…

O’BRIEN: Someone told me that you used musicians that actually didn’t like each other.

ENO: No.

No, there wasn’t a personal enmity between them. They weren’t hostile toward each other, but they were definitely from schools of music that were not compatible. One of them was from Hawkwind, another one was Phil Collins from Genesis, and certainly those two are quite far apart, and then Robert Fripp (formerly of King Crimson) on top of that, and then myself, who’s somewhere else again, and another guy who played in a kind of spoof rock band—they used to do covers of early Fifties songs. One way of working is just bring that group together and encourage them to stick to their guns, not to do the thing that normally happens in a working situation where everyone homogenizes and concedes certain points—so eventually they’re all playing in roughly the same style. I wanted quite the opposite of that. I wanted them to accent their styles, so that they pulled away. So there would be a kind of space in the middle where I could operate, and attempt to make these things coalesce in some way. In fact quite a lot of my stuff has arisen from that.

I have also worked from very mathematical and structural bases, but in general that hasn’t been so successful.

O’BRIEN: Do you mean Discreet Music?

ENO: No, that was done in a very peculiar way. There’s no other piece I’ve done that’s like that. The reason for doing that was that Fripp and I were going to do some concerts, and I wanted to compile some tapes that would be used as drones for us to work on top of. They were just ambiance tapes really. That particular day it was getting very close to the beginning of the tour and I wanted to get quite a lot of these done, so we had a lot of choices. I set that particular system up, which involved a delay system that I’ve been using for quite a long time, and a self-programming synthesizer, which has a built a built in memory so it can play a melodic line over and over. Once I got it going the phone started ringing, people started knocking on the door, and I was answering the phone and adjusting all this stuff as it ran. I almost made that without listening to it. It was really automatic music. The next day Fripp came around and we were going through these things I’d made and I put that one on by accident at half speed and it sounded very, very good. I thought it was probably one of the best things I’d ever done and I didn’t even realize I was doing it at the time. Since then I’ve experimented a lot with procedures where I set something up and interfered as little as possible. In fact I try to distract myself. I have techniques that keep my fingers off. I had a piece where I wanted a particular sound to come in at irregular intervals and I didn’t know how to decide what these points should be. I didn’t want to do it at a “nice place”—I wanted some more arbitrary technique. So I set the synthesizer up and then I placed these obstacles around the studio, and walked around them by different routes. Each time I passed the synthesizer I would hit it on whatever beat it happened to be closest to. That was another technique for suspending taste. I think I’ve forgotten your question.

O’BRIEN: You started out describing your more structural approaches. Is there anything you’ve done recently that’s an example of that method?

ENO: Yeah, but it’s not released. There’s a new series I’ve done of music designed for airports. It’s called Music for Airports, in fact. I’m going to release it on my own label.

O’BRIEN: It’s like muzak?

ENO: That’s right, but really beautiful too. I’m very, very pleased with one of the pieces. Again, it was done with a minimum of good intentions. I didn’t go into it thinking I’m going to make a very interesting piece of music here. I went into it thinking I just wanted to make something that would work in an airport that would actually make you think that flying was a pleasant thing to do instead of an unbearably uncomfortable thing, as I think it generally is. The particular piece I’m referring to was done by using a whole series of very long tape loops, like fifty, sixty, seventy feet long. There were twenty-two loops. One loop had just one piano note on it. Another one would have two piano notes. Another one would have a group of girls singing one note, sustaining it for ten seconds. There are eight loops of girls’ voices and about fourteen loops of piano. I just set all of these loops running and let them configure in whichever way they wanted to, and in fact the result is very, very nice. The interesting thing is that it doesn’t sound at all mechanical or mathematical as you would imagine. It sounds like some guy is sitting there playing the piano with quite intense feeling. The spacing and dynamics of “his” playing sound very well organized. That was an example of hardly interfering at all. When the piece was finished I listened to it and there was just one piano note I didn’t like. It seemed to appear in the wrong place, so I simply edited it out. A lot of the so-called systems composers have this thing that the system is always right. You don’t fiddle with it at all. Well, I don’t think that. I think the system is as right as you judge it to be. If for some reason you don’t like a bit of it you must trust your intuition on that. I don’t take a doctrinaire approach to systems.

O’BRIEN: Do you not read and write music by choice? I wouldn’t think it would be that useful for you.

ENO: It wouldn’t be very useful for me. There have been one or two occasions where I was stuck somewhere without my tape recorder and had an idea, tried to memorize it, and since a good idea nearly always relies on some unfamiliar nuance it is therefore automatically hard to remember. So on those very rare occasions I have thought, “God, if only I could write this down.” But in fact, quite a lot of what I do has to do with sound texture, and, you can’t notate that anyway. You can’t notate the sound of “St. Elmo’s Fire.” There’s no way of writing that down. That’s because musical notation arose at a time when sound textures were limited. If you said violins and woodwind that defined the sound texture; if I say synthesizer and guitar it means nothing—you’re talking about 28,000 variables.

What also happens with notation is that it reduces things to a language which isn’t necessarily appropriate to them. In the same way that words do, you get a much cruder version of what was actually intended. If you think of the way a composer or say a pop arranger works—he has an idea and he writes it down, so there’s one transmission loss. Then he gives the score to a group of musicians who interpret that, so there’s another transmission loss. So he’s involved with three information losses. Whereas what I nearly always do is work directly to the sound if it doesn’t sound right. So there’s a continuous loop going on.

You know that in order to copyright material somebody has to write it down for you. Any piece of recorded material has to be scored in order for it to be copyrighted. I’ve seen the scores of my things and they don’t resemble the music in any way. If you give them to somebody who has never heard the music and say, “What does this sound like to you?” they’ll play you something that has no relationship with the music it derives from. Notation simply isn’t adequate.

O’BRIEN: How do you work as a producer? How much do you add?

ENO: As much as anyone will let me, really. No. I work in various ways depending on what seems to be necessary. There are cases where it’s best to just keep your hands off and leave it alone. There are other cases where it isn’t so. When I was working with Talking Heads what would happen typically is that they would go out and start playing a track, and I would always run the tape. I always record everything, even a run through where you’re trying to get in tune. That’s a principle because sometimes when the situation isn’t clear interesting things happen, and they are worth listening to again. I would also have my synthesizer permanently linked into the control desk and I would sit in the control room next to the engineer, so that I could feed any instrument through as they were playing, and what I did would also go on the tape. I was kind of listening to what they were doing and picking out sounds and making new sounds from them. I instead of adding an instrument, which is the conventional over-dubbing idea, I was extracting ideas and rhythmic parts from what they were playing, perhaps using delays to create new rhythms within their own. Then they would come in and listen and we would select the interesting parts and that would become the basis for the next time ’round. This didn’t always happen. There were some things that were first take. But sometimes we would continually listen very carefully and pick up little playing ideas that may have been accidents, or accidents of interaction, and using those as the basis for doing it again. That would get the basic track down. Then listening to this track you might find a dead area where there was nothing happening, so we’d try chopping things out. There are two tracks on the album that radically changed their shape because of that. After that the overdubbing phase would start, which would involve whatever additions seemed to be necessary.

O’BRIEN: How do you keep up with the latest electronic devices? Do you do a lot of shopping?

ENO: No, I don’t go shopping that much. I always work in studios that have all the gimmicks. I love gimmicks. There are hundreds of manufacturers always producing decides that in general do the same things. Since they have slight structural differences if you take one and fool around with it and give it a good kick it will actually do something that it wasn’t designed to do. I have this relationship with my synthesizers. I’ve had them for so long, and I’ve never had them serviced, so that now practically all of their functions operate differently from what they were designed to do. They do very interesting things now, but that means nobody else can use them either. They’re not reliable in the strict sense. But with devices my technique is always to hide the handbook in the drawer until I’ve played with it for a while. The handbook always tells you what it does, and you can be quite sure that if it’s a complex device it can do at least fifteen other things that weren’t predicted in the handbook, or that they didn’t consider desirable. It’s normally those other things that interest me.

O’BRIEN: Do you have a trick bag that you can carry around with you?

ENO: For the Talking Heads album I brought a couple of things. I brought my little synthesizer that fits into a suitcase—it’s completely wacky, it does a whole lot of things that nothing else can do as far as I know. It’s actually denigrated over the six or so years that I’ve owned it and become a really unique and interesting piece of electronics. But I mostly used the studio devices, because I knew what they had. Generally I find I’m happy to use whatever’s around. If there’s nothing there I’ll make something. For example, one of the things I tried doing was getting a tiny loudspeaker and feeding the instruments off the tape through this tiny speaker and then through this huge long plastic tube—about 50 feet long—that they used to clean out the swimming pool in the place where I was staying. You get this really hollow, cavernous, weird sound, a very nice sound. We didn’t use it finally, but nonetheless we well could have.

O’BRIEN: Are the German studios you have used better equipped than English and American studios?

ENO: Technically they’re incredibly good. The popular idea of German technological efficiency really is true. At the studio we were working at there was a guy called Juergen Kramer who’s quite extraordinary. Have you ever seen a film called The Enigma of Kaspar Hauser or Stroszek—there’s a man in those films who used to be a lavatory cleaner and Werner Herzog decided he wanted him to act in his films. He plays a sort of dementoid creature. Well, Juergen Kramer is rather like that, sort of a country bumpkin. But he has an extraordinary intuitive grasp of very, very complex electronic systems. We were working on an MCI computerized desk, which is really a very complex desk, and occasionally it would go wrong. And he would walk in and say, “Ja, what ees da trobble? Ah, I tink it’s the capacitor in zis module.” And he’d rip things out and start pulling them apart. “Ja, here ees da trobble!” He would fix things in ten minutes that would honestly take any other technician half a day to fix. He had an intuition I’ve never seen in anybody before. And in fact, when Conny Planck who owns the studio first got this MCI desk Juergen went trough all the circuits and so on, saying “This could be better… This could be improved… This function should work like this.” He redesigned a lot of the functions and MCI came over and saw his redesigns and incorporated them in all future models. And the MCI team is not made up of dummies. In fact the team is made up of people who were involved in designing the Apollo missions and when that was closed down quite a few of them went over to MCI. They’re really the best brains. This guy Juergen Kramer is really an unbelievable person. His whole personality is typified, I think, but the fact that he takes as many sugars in his tea as tea will take. He puts in sugar until he has a saturated liquid.

O’BRIEN: When you collaborated with Bowie and Low was the instrumental side worked out in advance, or was it conceived in the studio?

ENO: The pieces all have slightly different histories. “Weeping Wall” and “Subterraneans” were originally done as part of the soundtrack of The Man Who Fell to Earth but for contractual reasons they weren’t used. So we took those tracks and worked on top of those. Actually, I didn’t work on “Weeping Wall” at all. Then there were two days when David had to go to Paris because he was being sued by someone, so rather than wasting the studio time I decided to start on a piece on my own, with the understanding that if he didn’t like it I would use it myself or something. I couldn’t face wasting the studio time. So I started working on that piece and in fact all the instrumentation was finished when David got back, and he put the vocals on top. That was “Warszawa.” It was a very clear division of labor. The other piece was “Art Decade.” That started off as a little tune that he played on the piano. Actually we both played it because it was for four hands, and when we’d finished it he didn’t like it very much and sort of forgot about it. But as it happened, during the two days he was gone I finished the one piece and then dug that out to see if I could do anything with it. I put all those instruments on top of what we had, and then he liked it and realized there was no hope for it, and he worked on top of that adding more instruments. In fact “Art Decade” is my favorite track of all.

On “Heroes” it wasn’t as clear-cut because we both worked on all the pieces all the time—almost taking turns. We used Oblique Strategies quite a lot. On one of the pieces—”Sense of Doubt”—we both pulled an Oblique Strategy at the beginning and kept them to ourselves. It was like a game. We took turns working on it; he’d do one overdub and I’d do the next, and he’d do the next. The idea was that each was to observe his Oblique Strategy as closely as he could. And as it turned out they were entirely opposed to one another. Effectively mine said, “Try to make everything as similar as possible,” which in effect is trying to create a homogenous line, and his said “Emphasize differences,” so whereas I was trying to smooth it out and make it into one continuum he was trying do to the opposite.

O’BRIEN: On your new album, on Bowie’s last few albums, and on Kraftwerk’s last two albums, there’s danceable yet advanced music. Do you think about breaking through to the discos?

ENO: Oh yeah, I do. What I would really like to do, if I could have a sort of kingship for a short time and organize the group of my dreams—I would make one group which would be a combination of, say, Parliament and Kraftwerk—put those two together and say, “Make a record.” Something that would be an extraordinary combination: the weird physical feeling of Parliament with this strange, rigid stuff over the top of it.

O’BRIEN: You get a bit of that with Donna Summer.

ENO: That’s right. Donna Summer was actually the beginning of this idea for me. When I heard that record I was so knocked out, I thought it was really making progress. Because to me a lot of the most interesting things in electronic music have come from that area—they haven’t come from people who are dealing with electronics exclusively. They’ve come from people searching for gimmicks, something as banal as, “What kind of sound can we get now that nobody’s ever got before?” What I like about the Parliament/Funkadelic people is that they really go to extremes. There’s nothing moderate about what they do. It’s very extreme music, quite as extreme in some ways as Kraftwerk is. What I’m interested in doing is getting these two extremes and gluing them together, seeing what you have to do to make them work together.

The other thing I’m interested in doing is robot reggae. I’d like to get together with some reggae musicians and deliberately try to subtract the feel from what they’re doing, so that they play in a kind of really stiff white way.

O’BRIEN: Dub is a step in that direction. Some of it is quite abstract.

ENO: That’s right. Again there’s an incredibly extreme and interesting and sophisticated use of electronics that nobody seems to notice. They don’t notice that it’s electronic music. They always focus on people like me who use synthesizers, right, which are explicitly electronic and therefore obvious. “Ah, yes, that’s electronic music.” But they don’t realize that so is the concept of actually taking a piece of extant music and literally re-collaging it, taking chunks out and changing the dynamics radically and creating new rhythmic structures with echo and all that. That’s real electronic music, as far as I’m concerned. I’ve got plans to do a dub album actually.

O’BRIEN: Yes, I have. I did a bit in Nassau. While I was there an engineer called Carl Peterson was working on Althea and Donna’s album. I know him and I went in one day as he was setting the track up and I said, “Can I try it?” I’d always really wanted to, and I started switching and doing things and it really works with reggae. It’s so easy. I tried doing it with rock music and it doesn’t happen. You can’t just play the board. But with reggae it works easily. I suppose it’s because all the instruments are rhythm instruments, so that’s whatever’s left is still playing rhythm. Whereas with rock you have a division of rhythm instruments, melody instruments and vocal lines. But with reggae it’s very easy. In fact I even went to the extent of trying to make mistakes, trying to do it so it didn’t work, to see how far off you could get. I’d hit things off the beat or bring in quite the wrong instruments and it still sounded all right. It’s like magic. It’s like sculpture in fact. Whereas most of the techniques of Western engineering as opposed to Jamaican engineering are additive, like painting, where you built something up. But reggae is like sculpture. You have something and you chop stuff away until you’re left with the shape you want. There’s a record by Dr. Alimentado called “Life All Over” that’s one of the great dub records of all time. It’s so bizarre, because apart from anything else he’s set up an echo which isn’t a simple one. The echo is two thirds of a beat long, so it forms incredibly peculiar cross rhythms. And they work. It’s a funny physical feeling. It’s like some weird waltz time over this very distinctive reggae.

O’BRIEN: What do you think about flying saucers?

ENO: I wish there was a serious investigation into them that wasn’t conducted by crackpots. Unfortunately nearly all of the people who are interested in them kind of manufacture the evidence to fit the theories rather than the other way around. So it’s very hard to find any dispassionate treatment of them. Maybe there isn’t any scientific basis in which case that’s why you never see any scientific evidence.

I saw one when I was young, you know. When I was seven I saw a flying saucer over our house. It was visible for quite a long time, four or five minutes. It wasn’t a saucer; it was sort of a cigar shaped thing. Having seen this I forgot about it. Which might sound strange, but I actually did forget about it for many years. And I remembered it with quite a start one day and I thought, “Now do I really remember this, or did I manufacture this memory?” So I wrote to my sister who had moved to America a long time before, and mentioned it as a very vague question: “Do you remember whether we ever saw anything in the sky together? If you do describe it.” She wrote back and described it exactly as I had remembered it, so I figured that I actually had seen it unless we mutually manufactured this myth. So I’m prepared to believe in their existence, or in a phenomenon strong enough to create the impression of their existence in your head.

THIS INTERVIEW ORIGINALLY APPEARED IN THE JUNE 1978 ISSUE OF INTERVIEW.

Two weeks ago on Dr. Phil, Shelley Duvall made her first public appearance since retiring in 2002, and revealed that she has a mental illness, leaving audiences baffled and concerned. Duvall told Dr. Phil‘s host Phil McGraw (a formerly licensed psychologist), that her Popeye costar Robin Williams is still alive as a shapeshifter and that she has a “whirling disk” implanted inside of her leg, among other things. She concluded, “I’m very sick. I need help.” According to Deadline, the Actors Fund has reached out to Duvall’s family to assist in her recovery after Phil McGraw announced that the actor refused treatment. The Dr. Phil episode, which has since been removed from the show’s website, angered audiences, who felt that The Shining actor had been exploited. Vivian Kubrick, daughter of Stanley Kubrick, who directed Duvall in The Shining, tweeted demanding a boycott of the episode, calling it “purely a form of lurid and exploitative entertainment.”

As a nod to cheerier times, we’ve reprinted Shelley Duvall’s cover story fromInterview‘s September 1977 issue. The actress was set to begin filming The Shining with Jack Nicholson within the next few months, entering what would become the peak of her career. In the wake of the arrest of infamous serial killer “Son of Sam,” Duvall told Andy Warhol and Bob Colacello about summering in East Hampton, being discovered on location as an actress, and her ironic fear of horror movies. —Natalia Barr

Shelley Duvall Before The Shining

By Andy Warhol and Bob Colacello

[Redacted by Chris Hemphill]

Thursday, August 11, 1977, 8:30 p.m. Andy Warhol and Bob Colacello are dining with Shelley Duvall, the star of Three Women, at Quo Vadis, 26 E. 63 St. Shelley is wearing a bright pink cotton dress that flares out below the hips, bright green linen boots, and a bright pink and green silk shawl. She speaks slowly and softly.

[Tape #1, Side A.]

ANDY WARHOL: This is a whole new table. I’ve never sat on this side before. Are you staying out in East Hampton most of the time?

SHELLEY DUVALL: Yes, for most of the summer. I come back about two days a week usually.

WARHOL: Son of Sam was on his way out there.

DUVALL: I just heard!

[Son of Sam]

WARHOL: How could a Berkowitz kill a Moskowitz?

DUVALL: That’s the first thing I thought.

WARHOL: It’s too terrible.

BOB COLACELLO: What would you like to eat?

[orders]

WARHOL: Where did you learn French?

DUVALL: Not from my father.

WARHOL: Duvall is a French name.

DUVALL: My father’s half-French and I’m whatever’s left.

WARHOL: Where were you born?

DUVALL: I was born in Fort Worth but I never lived there. I was visiting my grandmother at the time.

WARHOL: I don’t understand.

DUVALL: My mother was visiting my grandmother when I was born. But I grew up in Houston. I lived there until ’73 and then I moved to Los Angeles.

WARHOL: When did we meet?

DUVALL: You met me in 1970 when I’d just finished Brewster McCloud and was about to do McCabe & Mrs. Miller. Bill Worth told me, “Come down to the Factory and meet Andy Warhol,” and we got there and you weren’t there but we looked at pictures. And I remember the time you told me, “I stayed home from Elaine’s birthday party to watch you on Dick Cavett.” I was so flattered!

COLACELLO: You’re such a charmer, Andy.

WARHOL: But it was true.

COLACELLO: So what’s this new movie you’re doing with Jack [Nicholson]?

DUVALL: It’s from a novel written by Stephen King, who wrote Carrie. It’s calledThe Shining and we start shooting somewhere between December 1 and February 1. Stanley Kubrick’s writing the script now. He’s directing and it’ll be shot in London and Switzerland for 15 to 25 weeks—a long shoot.

COLACELLO: Is it a big cast?

DUVALL: No, it’s Jack and myself and a five-year-old boy, basically. And there’s a psychiatrist and an ex-gardener at the place where we’re caretakers. It’s very frightening. When I first heard of it I was wondering why Stanley Kubrick would want to do this film and then I read the book and it turns out, I think, to be really primal about fears and about the fears that one has in a relationship with another person.

WARHOL: It sounds like it could be a Robert Altman film, too. Three Women was terrific.

DUVALL: Bob knows me very well and he knows my limitations.

WARHOL: That story was fascinating.

DUVALL: I loved that story. That was an actual dream that Bob had. He had the dream on a Saturday night and he called me up on Sunday morning and said, “Shelley. I just had this incredible dream. Part of the dream was that I woke up and told my wife and wrote it all down on a yellow legal pad and called my production assistant and said, ‘I want you to scout locations for me,'” and then he woke up and discovered he hadn’t told his wife and he hadn’t written it down. It’s amazing—within a week he had the money for the film and we started shooting a month later.

WARHOL: Janice Rule is one of my favorite actresses but her style of acting was so different from yours and Sissy Spacek‘s.

DUVALL: I was just going to tell you it was actually just two women in the dream—Sissy and I. But I think someone like Bergman or Antonioni had already done a film called Two Women.

WARHOL: No, it was Sophia Loren. That was the one where she came out of the ocean. She won an Academy Award for it.

COLACELLO: Did you ever think you wanted to be an actress?

DUVALL: Never.

COLACELLO: How did you get started?

DUVALL: It’s a long story but I’ll tell you. I was living with my artist boyfriend at his parents’ house in Houston and we had a lot of parties and people would come who we didn’t know and his parents’ friends would come—they were really good parents—and one day I was giving a party and these three gentlemen came in and I said, “Come in, fix yourself a drink, make yourself at home,” and I continued showing all my friends Bernard’s new paintings, telling them what the artist was thinking. And they said they had some friends who were patrons of the arts who’d like to see the paintings so I made an appointment, brought the paintings up and showed them one by one. I lugged 35 paintings up there. And instead of selling some paintings I wound up getting into a movie.

WARHOL: They were testing you out?

DUVALL: Yes, they said, “How would you like to be in a movie?” and I thought, “Oh, no, a porno film,” because I’d been approached for that when I was 17 in a drugstore.

WARHOL: What did you do?

DUVALL: The guy left me with the bill for the Coca-Cola. So this time I said, “No, thank you,” and they called my parents’ house and got hold of me and after a while we became such good friends that I had no fear. I said, “I’m not an actress.” They said, “Yes, you are.” Finally, I said, “All right, if you think I’m an actress I guess I am.”

WARHOL: But what were they doing there?

DUVALL: They were on location.

WARHOL: But what made them come to the house? Were they just looking for something to do?

DUVALL: Somebody at the party had called them up and told them if they were bored in Houston we gave a lot of parties. When the film was over I thought it was just an interlude in my life. But three months later I started work on McCabe & Mrs. Miller. Actually during Brewster McCloud I’d already signed a five-year contract.

WARHOL: I guess things really do happen at parties.

[contracts]

COLACELLO: But you never studied acting?

DUVALL: I went to Lee Strasberg a few years ago because I’d heard such good things about him but I went to two lessons and it just wasn’t for me. That’s one piece of advice Robert Altman gave me at the very beginning—never take lessons and don’t take yourself seriously.

WARHOL: He’s right. It’s all magic. The problem is knowing how to keep it once you get it.

DUVALL: I make my own decisions. And I never turn down anything without reading it. Other than that… I’m sort of at a loss for words. It was hard to move here, actually.

WARHOL: You mean you’re living here for real?

DUVALL: I moved here in October.

WARHOL: To East Hampton?

DUVALL: No, to New York from L.A. East Hampton’s just a summer place.

WARHOL: Some people live there year-round now

DUVALL: I like that idea. I think it would be just as nice in the spring and fall as in the summer. Our place looks like Japan. It’s got those short needlepines, little pebbles and everything.

WARHOL: Montauk doesn’t have much of a beach but it’s very beautiful. It’s all rocks.

DUVALL: I want to see the lighthouse.

WARHOL: If you’d seen Peter Beard’s place you’d be so sad now. It just burned down last week with all his work inside.

DUVALL: How terrible. Was it lightning?

WARHOL: No, the boiler room.

DUVALL: God, the boiler room! You should read The Shining.

WARHOL: Does it happen in a boiler room?

DUVALL: You’ll see. It’s frightening.

WARHOL: Carrie was so good.

DUVALL: I still haven’t seen it. Scary movies frighten me. I still haven’t seen The Exorcist.

WARHOL: It’s really good. It isn’t even scary. It’s just intelligent.

DUVALL: I like to see just about every movie that comes out that strikes my fancy.

WARHOL: I’m always worrying about bombs in movie theaters, though. My favorite kind of movies are unsuccessful ones because there’s no one there. And then I like…

[End of Side A.]

[Tape #1, Side B.]

DUVALL: …The Omen.

COLACELLO: Why did you move to New York from L.A.?

DUVALL: For several reasons. I’d always wanted to move to New York, from the first time I came here. And then I guess Paul [Simon] was an extra added attraction—a New Yorker boyfriend.

COLACELLO: That’s a nice way of putting it. He’s working so much now.

DUVALL: He’s always working. There’s so much energy here. That’s why I like it, despite everything.

[Son of Sam]

WARHOL: How can people see something on TV and then they can’t wait to read about it in the newspaper? Why is that?

DUVALL: Maybe it’s more real.

WARHOL: Maybe.

DUVALL: New Yorkers have a fascination with the daily paper. I could never understand that when I came here. And I could never understand how people get up to see “The Today Show.”

WARHOL: It’s easy if you have a pushbutton. It’s great. And if you turn it on at seven you see the news three or four times which is even better—all the repeats.

DUVALL: I did an interview with Gene Shalit and I never saw it because I could never wake up early enough.

COLACELLO: Would you like some dessert?

DUVALL: I’m looking over at the chocolate mousse but…

WARHOL: I was supposed to go to the pimple doctor this morning and I never went.

[pimple doctors]

DUVALL: Well, everybody’s got something about them. But did you hear about the guy with no feet?

WARHOL: No, who?

DUVALL: I’m just kidding. But here we’re complaining about pimples and…

WARHOL: Oh, I know. We’re so lucky.

DUVALL: We really are.

WARHOL: So many people have so many problems. When you think that health is wealth, you’re so grateful just to be normal, more or less. Aren’t you?

THIS INTERVIEW ORIGINALLY APPEARED IN THE SEPTEMBER 1977 ISSUE OF INTERVIEW.

New Again runs every week. For more, click here.