New Again: Beck

The lineup for New York’s Governor’s Ball has just been announced and there are plenty of marvelous artists to look forward to—Santigold, Major Lazer, Passion Pit, LCD Soundsystem and Beck, our favorite Scientologist. We first spoke to Beck in Summer of 1996, after “Loser” had catapulted him into the public eye (“if you make the karaoke scene, you have really arrived”), when Beck was cementing his pop-star status with the album Odelay. If anything can make you nostalgic for the early to mid-’90s (and want to Netflix Reality Bites) it’s Beck discussing (and decrying) the concept of “the slacker.” Read our full interview with Beck reprinted from our August 1996 issue below:

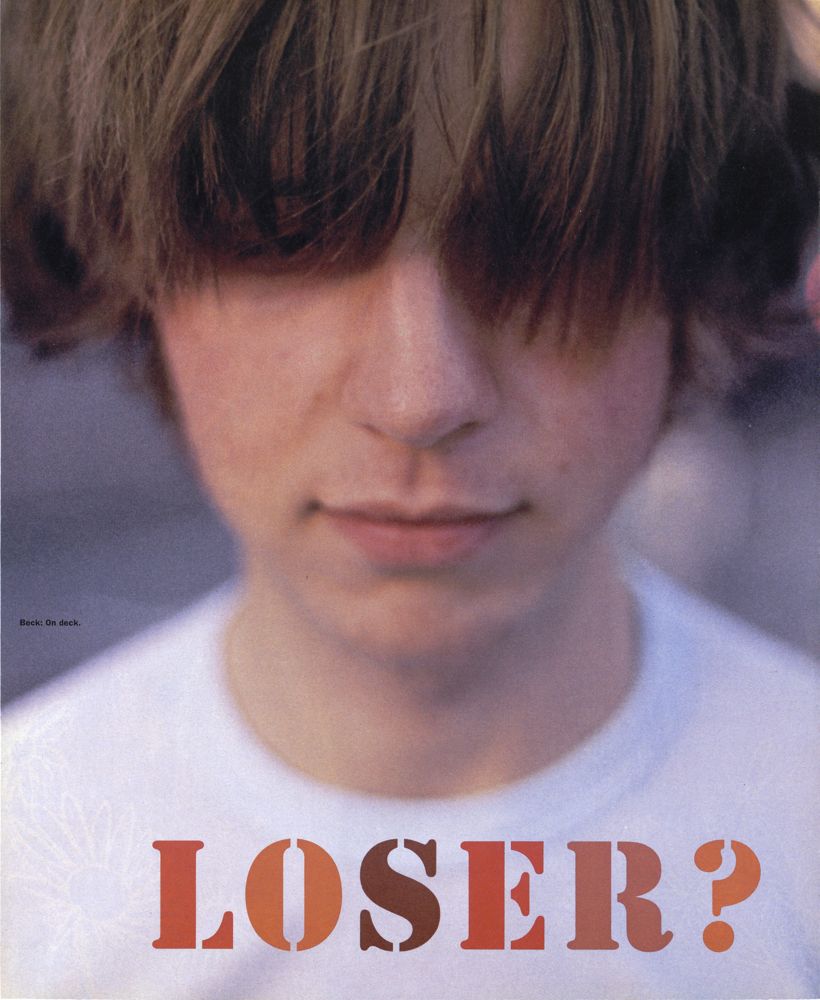

Loser?

by Ray Rogers

Beck’s first single, “Loser,” led to the perception of him as a freaky kid with an inferiority complex. But what people missed was his intelligence, street-level humility, and perfect grasp of the commonplace. What Walt Whitman did for riverboat captains, Beck does for karaoke and jeans on his new record, Odelay, which is a major winner.

Even after a solid year of hearing “I’m a loser, baby, so why don’t you kill me?” blaring on the radio and on MTV around the clock, nobody actually took Beck Hansen up on his 1993 offer and did him in. The press did a good job of haranguing him, though, slamming the singer as a flash-in-the-pan novelty and harnessing him with the dreaded “slacker” tag. But Beck was no Vanilla Ice-type flavor of the month. Instead of sinking back into obscurity, he’s having the last laugh: Odelay (DGC), his latest album, is one hell of a second act. An action-packed speedway of hip-hop, folk, funk, and blues, produced by the Dust Brothers—revered mixmasters who guided the Beastie Boys to previous ill heights—the record mines the ’70s, ’80s, and ’90s for its best moments and mocks the decades fickle fads (“Everybody say, ‘Ooh, la la, Sasson!'” goes one shout-out). It’s got a single—the deliciously anarchic “Devil’s Haircut”—that could give “Loser” a run for its money and emerge as this year’s feel-bad anthem.

We met Beck at Travel Town, a children’s train theme park located about a half hour from his new home in the Silver Lake area of Los Angeles. Pulling up in his pale green ’74 Ford pickup, the definitive overgrown kid looked youthful but scruffy, with a scattering of blond fuzz on his face and his dark shades clasped together by a paper clip. As a demented version of “B-I-N-G-O” whooshed out of a miniature train’s speakers, we sat down to discuss life after “Loser,” and his symphonic, sample-adelic new record.

RAY ROGERS: Who picked this place?

BECK: David Geffen picked it. No, I picked it because I do all of my traveling here. I like to ride trains that go nowhere. [laughs]

ROGERS: There are lyrics on your new record about that: go-nowhere places and dead-end situations.

BECK: There’s some about Southern California, which is sort of a dead-end place. It’s like the bottom of the hill; everything just sort of slides into it. This whole area is kind of transparent. It doesn’t really have any history, and what history it does have gets eaten up, dug up, and turned into something else.

ROGERS: What do you appreciate about Southern California?

BECK: It’s anonymous. There’s cool things happening below the surface. It can be a Chinese mall in Monterey Park that looks totally generic, but then there’s a gambling den and weird movie theaters where you can buy a bean-curd popsicle or some crazy lizard.

ROGERS: How does living here affect your music?

BECK: I’m not sure about this album, but the last one had to do with where I was living. [train whistle blows] All these things came out of the landscape, like horrible fumes, something acidic and rancid that you breathe in. Like the smog—you don’t want to breathe it, but you can’t help it ’cause it’s there. You have no choice. And it takes over your whole being. But a lot about making a record is an unconscious thing. Just something that you do. You can’t meditate on walking or certain human habits. You concentrate too much on the way you walk and you’ll start walking pretty weird.

ROGERS: Do you think that doing interviews in places like this is a way to make you seem “offbeat”?

BECK: Oh, definitely not. I think trying to be offbeat is the most boring thing possible. I think it’s silly when photographers want to make you look all interesting, and it’s just like, “Take the damn picture.” I want to look boring. It’s way more interesting than them hanging you up from a harness and feathering you and making you wear some see-through jumpsuit. Give me a break. I’d rather have a photo from Kinko’s. Coming here is just an excuse to be outside.

ROGERS: Why did you call your record Odelay?

BECK: It comes from Chicano slang—orale! It’s sort of an exclamation of “all right, things are all right.” I’ll say “What’s up?” to my friend, Andy, and he’ll go “Odelay!” [laughs].

ROGERS: Your songs are such a hodgepodge of musical styles that somehow perfectly fit the evocative narratives. What comes first?

BECK: Usually the music inspires the lyrics. The lyrics just sort of fall off like a bunch of crumbs from the melody. That’s all I want them to be—crumbs. I don’t want to work any kind of fabricated message. Sometimes I’ll have an idea for a story or have a subject and that will inspire lyrics, but most of the time, hopefully, they already exist somewhere else.

ROGERS: You’re channeling them?

BECK: It’s more like blowing your nose, you know. It’s not really an elevated thing. [laughs]

ROGERS: For some people it is.

BECK: Yeah, some people build it up, it’s a little pretentious, I think.

ROGERS: Some people might think that saying songwriting is “like blowing your nose” is pretentious.

BECK: Pretentious? Well, I meant blowing your nose in the way of just living your life, and I would never separate music from life.

ROGERS: Why do you think folk music and hip-hop intersect so well in your songs?

BECK: Well, it’s all music that comes from nonprofessional areas. With hip-hop, you didn’t need a studio, you just needed some turntables and some kind of recording thing. You could do it in your living room. That’s the spirit of hip-hop. And folk wasn’t about recording studios and all that. I guess they’re both nonelitist forms of music.

ROGERS: You put several ’80s references on your record, like Sergio Valente, Sasson…

BECK: Yeah, there are certain fashion references, but I think that’s more an attempt to draw attention to the fleeting nature of hipness. I’m distrustful of fashion.

ROGERS: That brings to mind the way “Loser” went from being extremely popular to suddenly being seen as a joke.

BECK: That song’s sort of a one-street town, or one street of a town. You don’t want to go up and down the same street all the time. That song was not intended to go where it did, or maybe there wasn’t enough gas in the car for it to drive as far as it went. [laughs]

ROGERS: [laughs] Do you think that song still prompts people to assume you’re some slacker dude?

BECK: I have a lot of problems with slacker, the term, the idea, the myth, the madness. [laughs] The mystery, the mindlessness, ultimately the mirage. This supposed apathy… I don’t know, isn’t being a slacker kind of a middle-class thing? It seems like you have to have money to be able to, you know, not do anything. I’ve never been able to relate to apathy. I’ve always been doing stuff, been in action, making music or working just to get by.

ROGERS: Does it make you uncomfortable to have all these people who don’t know you define you as a typical slacker?

BECK: It’s funny. I mean, the person they think I am is as big a stranger to me as he is to them. What do you think when you think of a slacker? One who sits around and watches TV all the time?

ROGERS: Disaffected, twentysomething—

BECK: You see, I’m affected by things. This boredom just doesn’t exist. It never did. When I was young I had to create my own amusements. I think a lot of what I’m trying to do musically is draw upon the refuse and make something interesting out of it. It’s not out of a desire to be kitschy or retro or anything like that. If that’s the impression I give, then I haven’t figured out how to do it right. I’m still learning like anybody else. There are things going on below the surface other than just a bunch of glib references to ’70s and ’80s waste culture.

ROGERS: What do you think people heard in “Loser”?

BECK: The vacuous ’80s pop song had a sense of winning and being on top, and I think there’s a certain novelty in a song that came out on the radio and said, “I’m nowhere,” you know, “I’m a loser.” [laughs] Also, that song doesn’t have a very exalted beginning, it doesn’t come from a place, it doesn’t mean anything. I didn’t go to high school. I never felt connected to people my age. When I was doing that song I had no idea what a “slacker” was. It was like a talking blues. It didn’t have anything to do with what was going on in popular music.

ROGERS: Do you think people figured you would just disappear into the woodwork?

BECK: Sure they thought that. I remember reading all the time, “There’s only two words for Beck: Tommy Tutone.”

ROGERS: What were you doing when other kids were in high school?

BECK: I was working. Started playing music, working and listening to Mississippi John Hurt, and riding the bus to work. Not much.

ROGERS: What were you singing about at that time?

BECK: Same stuff: filing cabinets, bus stops, cuff links. [laughs]

ROGERS: [laughs] So, to quote your first single, “Where It’s At,” are you “AC/DC”? Do you “swing both ways”?

BECK: No, I’m sorta battery powered. I’m really fascinated by lingos and colloquialisms that are out-moded and have gone by the wayside. I love the way people spoke in the ’30s, and the amazing slang of the mid-’60s abd ’70s. [excuses himself] I have to take a crippling piss before we continue this. [Beck returns from the bathroom]

ROGERS: Your songs, even your language are full of very visual imagery.

BECK: Yeah, I don’t want to tell the story, I just want to give clues to it.

ROGERS: Your songs do have a somewhat surreal quality to them. Could you, for instance, decipher the narrative of “Sissyneck” for me?

BECK: Oh, it’s the morning after a full night of line dancing and cocaine. It’s the achy-breaky heart after the triple bypass. It’s a get-together at the recreation-center Ping-Pong tournament.

ROGERS: Speaking of recreation, there are a few references to karoake on the new record. Do you ever do it yourself?

BECK: No, I’ve always been afraid of it. One time I was walking through Bourbon Street [in New Orleans] and there was a karaoke machine with about five frat boys onstage, beer mugs in hand, try to do “Loser” and not knowing what the hell the words were. They did this sort of mumbling and head butting. I think they finally just faded it out. Someone showed me a grunge karaoke tape and “Loser” was actually on it.

ROGERS: Little did you know when you wrote that song at three in the morning…

BECK: Yeah. If you make the karaoke scene, you have really arrived.