The Undertaker: Swans’ Michael Gira

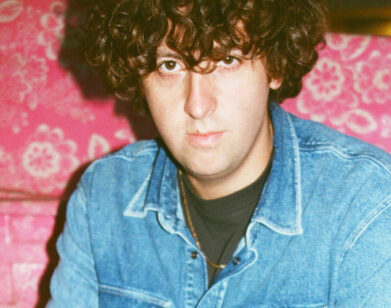

MICHAEL GIRA (FAR RIGHT) AND THE FLOCK OF SWANS.

PHOTO COURTESY OF OWEN SWENSON.

When it was announced early this year that post-punk band Swans would be resurrected for a new album and tour, press began telling tales of the group’s legendary early days: brutally loud shows, with two bassists and two drummers that together made a deafening primal beat. For his part, frontman Michael Gira used brute, guttural vocals and hazardous performance tricks, which on one tour included locking venue doors to trap audiences inside for the duration of a violent set.

Founded in New York in 1982 as part of the No Wave scene, their contemporaries once included dissonant drone act Mars and an early incarnation of Sonic Youth. But over a career that spanned 11 studio albums until they disbanded in 1997, their style grew beyond raw barking rhythm to encompass acoustic and world music elements, drone and field recordings. Heavy music makers like Godflesh and Ministry have acknowledged their influence, but Gira’s also fostered a new generation of experimental folk music through his label Young God Records, formed in 1990 and home to Devendra Banhart, famed minimalist composer Charlemagne Palestine, as well as his own band Angels of Light.

The new Swans album, My Father Will Guide Me Up a Rope to the Sky, was released last week, and their New York shows over the weekend had already been sold out for months by the time we spoke with Gira. He was driving through the mountains between Columbus, Ohio, and New York City, on the eve of Swans’ first show here in 13 years.

KAYLA GUTHRIE: Many of your songs have spiritual imagery. Did you have a religious upbringing, or is this something that’s developed over the years in the course of writing music?

MICHAEL GIRA: It has to do with the conjoined aspirations of what I want from music and what I want to experience in life before I die: wanting the music to elevate, to make you levitate, almost like having it erase your body and lift you up to heaven. It’s also an aspiration to find what’s behind things in everyday reality, like having an extended session of tantric sex with someone you love: a slow, gratifying, sensual thing, where tension builds and builds until finally you just see this white light and you reach something bigger than yourself.

GUTHRIE: Were you making music or art from a young age?

GIRA: I went to art school and never thought I’d be a musician, but then punk rock came along in the late 70s and kind of ruined my life. [LAUGHS] So I quit art school to get involved in music and I’ve been doing it ever since.

I guess I’ve always strived for the big sounds. A pivotal experience in my early days was seeing Pink Floyd—before they sucked—in 1969 at a rock festival in Belgium. Of course, I was on LSD, and it was a really out-of-body experience. That psychedelic impulse of great music from the 60s is sort of the core of what Swans is doing.

GUTHRIE: Do you see music as a higher art form than visual art?

GIRA: Oh, no, I don’t make distinctions like that. The main reason that I stopped art was that I just was questioning what I was going to do with my life, and art felt like this increasingly professional decision, where you’d go to university and do the right things and discuss “issues”, and that’s not what I really wanted from it. I liked disruptive things, and I noticed then—and it’s even worse now—that the art world was becoming so academic and elitist. All the lingo involved in being an artist was just completely bogus in my mind, so I just said Fuck this.

Punk rock at the time hadn’t yet become so stylized. It felt immediate and relevant. I gravitated towards that and learned new ways of making sounds. I liked the impulse to just make something happen, right now, on the spot, make it real.

The post-punk bands took the idea of not having to be a skilled musician to make compelling sounds. So me and my cohorts just worked with sound and rhythm. We didn’t worry about it being a song or not. We wanted to generate an experience.

GUTHRIE: I’ve read about your interest in Bob Dylan and Howlin’ Wolf, American blues and folk music…

GIRA: Oh yeah, those guys are great; to me Howlin’ Wolf and Muddy Waters are just geniuses of American culture, right up there with great writers and presidents. They changed the course of history. In Muddy Waters’ case, he’s this guy who grew up picking cotton – you know, with outdoor plumbing, completely poverty-stricken—and managed somehow to affect the course of modern music. What a titan! And I love his voice, it just gives me immense pleasure: the way he can go from this bellowing, low, guttural groan into this falsetto suddenly I just find both comical and profound.

GUTHRIE: Such a contrast to nowadays, with so much processing involved in making songs. Do you think of yourself as particularly American?

GIRA: [LAUGHS] I’m very American, yeah. A straight shooter and all that stuff.

GUTHRIE: I’ve heard you live in the Catskills. When did you move out there?

GIRA: Four years ago. It’s something that I’d been wanting to do for centuries, but I finally managed to get the funds together and buy a house. I like going back to the city, but it holds a lot of dark memories for me. There was a lot of extreme poverty and hardship in the early days, and it’s hard to divorce yourself from that now, when you walk down the same streets and remember being so poor and everything being so difficult. I was really pleased to get out.

GUTHRIE: Swans are famous for these harsh songs like “Beautiful Child.” I was watching the 80’s live video on YouTube…

SWANS PERFORM “BEAUTIFUL CHILD” IN 1987.

GIRA: I wrote that song after reading this bit in the bible about Abraham and Isaac—it was just sort of a thought about where morality begins and ends, and the importance of making a choice. I know that video; it’s kind of intense, isn’t it?

GUTHRIE: A user had commented: “You’re not watching music, you’re watching an exorcism. We’re all lucky Michael Gira had musical talent or else he’d probably be doing serial killings.” Obviously, that’s an exaggeration?

GIRA: That’s kind of how our music is now actually, so not really. They’re not songs, that’s for sure. At least live, I think you’ll experience that it’s more of an undertaking: sort of like being in a sweat lodge on LSD or something.

MY FATHER WILL GUIDE ME UP A ROPE TO THE SKY (YOUNG GOD RECORDS) IS OUT NOW.