Merchandise’s End Notes

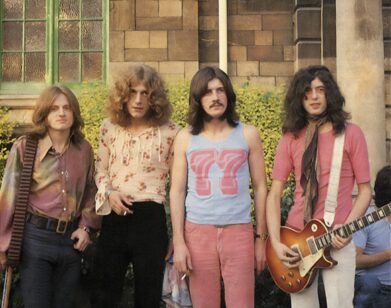

ABOVE: MERCHANDISE (L-R): CHRIS HORN, ELSNER NINO, DAVID VASSALOTTI, CARSON COX, AND PATRICK BRADY. PHOTO COURTESY OF TIMOTHY SACCENTI

When Merchandise formed in Tampa a little over half a decade ago, it was a three-piece band comprised of Carson Cox, Patrick Brady, and David Vassalotti. All three were already veterans of the area’s thriving punk and hardcore scenes, which led to some confusion when Merchandise’s own music leaned more towards a New Wave revivalist, miserablist-pop direction—more Depeche Mode than GG Allin (though the band’s still more likely to mention the latter in conversation).

The band also never intended to do interviews for the project, which is why it was still a little strange for them to meet Interview at a Williamsburg café a few months ago to discuss their new full-length, After the End, which follows last year’s well-received EP Totale Nite, 2012’s breakout LP Children of Desire (which features “Time,” a basically perfect noise-pop song), and 2010’s Strange Sounds in the Dark. They weren’t avoiding press on purpose, though, as Vassalotti explains: “We didn’t understand what it was, really. We just knew how to make records and talk people into letting us play at their house.”

“I would say we were just whatever the epitome of naïve is,” frontman Cox agrees. “The deepest, truest version of it.”

No longer: after a series of lineup changes that comes to feel, when you listen to Cox rattle it off, like a logic puzzle, the original three members acquired two more—drummer Elsner Nino and keyboardist/saxophonist Chris Horn. Together, they recorded After the End, an album that balances moodiness and pep in the same proportions that worked so well for The Cure and The Smiths. (One senses they might be a little tired of that last comparison—Cox’s voice sounds similar enough to Morrissey’s that the specter of a question about him comes to haunt our interview like an inside joke.)

Despite its title, After the End isn’t an explicitly post-apocalyptic album—except in the sense, maybe, of a personal apocalypse. “It’s just the end of life as you know it,” Vassalotti says. “It’s venturing into the unknown. It’s doing something new.”

ALEXANDRIA SYMONDS: You guys have come to New York enough that probably you have some kind of routine now, right? When you come here, you feel welcome?

CARSON COX: For sure. We have so many friends here. Elsner was living here before he joined the band.

SYMONDS: Did you go back to your old place to do laundry?

ELSNER NINO: No, because that place no longer exists. Me and my roommate moved out, and I stayed last night at my friend’s house that lives above the Commodore.

COX: We slept foot to foot on the same sectional.

NINO: I did laundry in that area.

SYMONDS: I wrote down a bunch of questions that I should ask you.

COX: They’re all about laundry.

SYMONDS: They’re all about laundry, every single one of them. So do you guys do a warm and then a cold rinse?

NINO: Just a cold spin.

COX: Elsner has a lace shirt that he has to have dry-cleaned. It’s a custom lace shirt.

NINO: I have one lace shirt.

SYMONDS: That sounds really nice.

COX: Show her the pictures.

NINO: I can’t find it on my phone, but I can find it on Instagram.

SYMONDS: Oh, wow! Now, do you normally wear some kind of…

COX: No bra.

SYMONDS: No bra. But I can’t see your nipples.

COX: That’s because Elsner doesn’t have any nipples. He was born without them.

NINO: They’re there. They’re dark and they’re meaty.

SYMONDS: Does it have strategically placed flowers or is just the way the shadows work?

COX: I think your chest is just so hairy that you can’t see your nipples.

SYMONDS: You took your time signing and were being courted a lot by labels. Did anything stick out as being especially absurd or insane about the whole process? Were there A&R guys being like, “Listen, here’s the future of Merchandise”?

COX: Coming to Brooklyn was pretty funny. I’ve been coming here for years, but after that, it was very different. Not so much labels, but the manager game is the most corny, weird thing. Just all the bells and whistles of schmoozy bullshit. I guess I’m just not used to that, because I grew up in Tampa and when I would come to the city, I would just come to the most fucked-up part of it, you know? Wherever I could afford to be. I think that press and music labels and show business in general is really confusing to the public, which is why they’re so hypnotized by it. We did talk to major labels.

SYMONDS: Which does mean something very different in 2014 than it did in 1998.

COX: It does, and in general, at least in this city, indie culture is the mainstream—I think a lot of people view 4AD and these labels as mainstream labels, because in cities like this, it’s everywhere. It’s like, [gestures toward the street] a painted advertisement for The Men. There’s a painted thing for tUnE-yArDs. That wouldn’t exist where we’re from.

SYMONDS: 4AD seems like it makes a lot of sense for you guys.

COX: I like to think so. We’re not making punk music, we’re making an experiment. We needed a home that was going to preserve that. I don’t feel like there’s one style of thing that comes out on that label, and they’re pretty gutsy. At the end of the day, that’s more valuable for us: a punk or bedroom label is cool, but it doesn’t really identify us. There isn’t one thing that I identify with, other than my band and my bandmates. 4AD didn’t have a problem with us doing whatever the fuck we wanted.

SYMONDS: You just said you’re not making punk music, which to me seems pretty obvious, now, but it also seems like something you have to continually explain to people.

DAVID VASSALOTTI: Reiterate over and over.

COX: Part of it is very, very limited explanations of who we are in magazines and zines and on websites. People would say. “They were all in these bands, so their band sounds like…”

VASSALOTTI: The interesting thing is that we all are still involved in punk music, but it’s just separate. Just because you’re into one thing doesn’t mean that it defines you or defines your musical taste. I still play with punk bands, I’m friends with a lot of punks, but I feel like they know that it’s a separate entity. It’s a different direction.

COX: Also, punk rockers define their identity through their music, for the most part. Not everyone’s like that—some people define it through their fuckin’ leather jacket. But I think that’s part of the reason why we had to clarify stuff, is because we come from a place where identity is deeply a part of it, and to break with that means that you’re phony, or you’re a poser, when in reality all we’re doing is being ourselves. We’re not interested in—

HORN: Posturing.

COX: Yeah, or being one thing. I also don’t really identify with punk rock anymore because why should I? It’s 2057.

NINO: It’s not just leather jackets; it’s literally like leather jockstraps, gloves, gag balls.

COX: And on top of that, it’s like a thin identity, too, because it doesn’t deal with subversion anymore. It’s turned into a daycare. Punk rock is stupid. It has nothing to do with rebellion. I mean, they teach punk at NYU, how punk is that? At what point are we going to stop pretending? I realize that society is so stupid that they need a word for something to be a thing. But we need to change the word to exclude punk, and the word I use is subversion.

SYMONDS: The thing you said—”to break with the punk scene means you were a poser all along”—do you still find that to be true? That just seems like such a 19-year-old frame of mind.

COX: Yes, I think it’s even worse. Straight-edge 40-year-olds are worse than anyone else. That’s not meant to be disrespectful to people who don’t want to be fucked up. I have plenty of friends that just don’t want to be drunk and don’t want to do drugs. I think that’s totally their prerogative, but the scene, straight-edge, middle-aged man… Punk rock is an old man’s game now. There are less and less young kids getting into it; it’s more about dudes that grew up with it that don’t identify with whatever the fuck is on the radio. It’s way worse. It’s bitterness.

SYMONDS: It seems like you guys did set out to write a poppy album, but there is such nihilism in the lyrics. It’s a dark album, if you were just reading them.

COX: We always play with language. Language is a big part of the band. I don’t know why they’re so negative. I genuinely do love depressing music; Jimmie Rodgers is one of my favorites, John Jacob Niles, Scott Walker, Brian Eno. Louis Armstrong. Some of the Louis Armstrong songs are way, way, way more fucked up than people realize.

SYMONDS: Like what?

COX: Like “Black and Blue.” It’s all about him being a famous black man and just being like, “What did I do to deserve this? Why do you treat me this way?” A lot of our lyrics come out of vibrations and energy. I would stay that’s the most powerful thing, more than musical influence.

SYMONDS: Can you explain that?

COX: Like a pull to something. Everything has its own aura, a little vibration or whatever. I’ve always been really into lights. Lights do something to my brain, the same way music does something to my brain. Poetry, talking, having conversations, being exhausted, feeling totally alienated in your own house, in your own room. All of these things vibrate and put something at you. They emit some kind of energy. Some things are more subtle. I think there’s a kind of vibration that exists over a super long period of time. Like living in the same house, the energy of the house. Energy is maybe an easier word to understand. The energy is very real. It’s probably the most real thing to me.

PATRICK BRADY: There’s something tangible there too, though. There’s the actual atmosphere in Tampa, constantly full of mosquitos invading your body. That’s resonant.

COX: I wrote a lot while sitting in the backyard. The backyard is all tropical vegetation. There’s lizards everywhere. Those kind of things pushed me to write this record, because I’d never written about some of the stuff on it, and part of it was because I just felt exhausted writing about the same thing over and over again. So trying to make a new record just meant trying to explore a totally new space. When I was writing it, I was worried that it was too easy, like I should be challenging myself harder, but by the time it was done, it was the hardest fucking record I had ever done. I was just so fucked up from it.

SYMONDS: What’s the refractory process like after you finish and you’re completely bushwhacked? What do you spend the next two to three weeks doing?

COX: I normally try to work on a video, or I write, or I do something that’s far away from music. Sometimes I don’t even want to listen to music afterward, because I’ve listened to so much that my ears hurt. I pretty much just jump into movies.

BRADY: We’re going to the Guggenheim tomorrow.

SYMONDS: What’s at the Guggenheim right now?

COX: It’s Italian futurism.

NINO: We should probably get there at noon.

SYMONDS: It’s a shame you guys missed James Turrell.

NINO: I went to that!

SYMONDS: That was awesome. If you’re into light, can’t beat it.

COX: I missed it. [pauses] I normally go to Ikea and just hang out in the lamp department.

SYMONDS: You guys have alluded, in interviews before this one—

VASSALOTTI: Is it about Morrissey?

CHRIS HORN: Let’s just get it out now!

COX: Well, before you say anything, I want you to ask the worst question you possibly can. We do interviews and I’m always disappointed that there’s never been a question where I’ve just been totally like… do you know what I mean?

VASSALOTTI: We want the worst question.

SYMONDS: Worst in what way, though? Worst like most cliché? Or that will offend you?

BRADY: No, like offensive!

COX: Sometimes I read our interviews and even if they’re good, I just wish something vicious happened in it, I wish there was some kind of blood…

VASSALOTTI: Some more racial slurs.

COX: Howard Stern, I feel like, is one of the best interviewers in the world, and that’s a very uncomfortable thing for a lot of people.

SYMONDS: Is it hard to find time to masturbate while you guys are on tour?

COX: [laughs] Not at all. I would say that’s the easiest thing in the world to do.

SYMONDS: Really? But you’re all together.

COX: We all just do it in the van. All at the same time.

HORN: Every major city has a Jack Shack somewhere nearby.

COX: Especially Philadelphia.

VASSALOTTI: Philadelphia is Jack City.

COX: One time I played a show at a frat house in Philadelphia. Pi Lamb. It was sick. That was a perfect example of how twisted and bizarre Philly is, because you can have a punk show at a frat house, and the people that ended up showing up were junkies, sorority girls, 12-year-old kids, a super-old dude that ended up passing out in the doorway of the show… Pennsylvania gives Florida a run for its money.

SYMONDS: Florida is the Twilight Zone of America.

COX: We get that all the time.

SYMONDS: Do you find that to be true? Or is it something the rest of America made up?

VASSALOTTI: It’s true. It’s a fucked-up place.

COX: It’s a super conservative place that’s really devoid of any kind of cultural advancement. When I was young, if it was 2004 in New York, it was 1998 in Tampa, or 1988. Always really, really behind the times. I’m 28, so my generation is on this weird cusp of all the change that happened where information became super fast. Even then I feel like there’s a lot of social taboos that are still way acceptable in Florida; in Tampa especially.

SYMONDS: Like racism?

COX: Not so much that, but I would say male-female roles, and it’s not reserved to white Anglo-Saxon Protestants. The Cuban population in my town is super, super conservative and very traditional: the men have a role, the women have a role, your sexuality is this, your gender is this, your politics should be this. If you want to socialize, you have to be this way, you can’t be that way. It’s perceived as a very square place, but it’s also vicious.

SYMONDS: Do you feel like, if you are by nature a creative person, it’s easier to be making art someplace like that—where there’s so much to react to—as opposed to doing it here?

VASSALOTTI: I think it gives you more motivation.

COX: I think it’s personal. I don’t think Basquiat would have made art in Tampa.

SYMONDS: You guys have said that you have this life where people in Williamsburg know who you are, and people in Indonesia are writing to request your lyrics; and then you have normal Tampa lives, and the people you grew up with don’t have a sense for your success as a band. Do you feel that split on a daily basis, or does it feel natural?

COX: I don’t think it’s that weird for people who make art to have double lives. Rimbaud went to Africa; George Méliès was penniless in Montparnasse, selling toys, and that’s how he died. If you ask them if they had a double life, I don’t even know what the answer would be. But at this point it’s been going so long, it’s just normal. Anything else would be kind of strange.

SYMONDS: How do you talk about what you do for a living with the people that you grew up with?

COX: Mostly we just don’t talk about it. If I do talk about it, I always get a sense that they don’t want to hear about it. We shot a music video in Tampa that was a huge production, with a huge crew, with a cinematographer…

VASSALOTTI: And we shot it in a place where, if you lived in Tampa proper or any of the suburbs, it was the theater where you went to on a field trip as a child.

COX: And even after doing that, if I tell my friends, they just don’t really care.

VASSALOTTI: I don’t want them to care!

HORN: Sometimes people assume we’re more rich and famous than we actually are.

BRADY: I’ve had a couple people tell me, like, “Do you know anyone who writes at Noisey? I want them to plug this shitty festival I’m doing.” Just because I’m in a band that’s featured in an article on some fucking website doesn’t mean I know someone and can be like, “Hey, can you do this favor for me?”

SYMONDS: I think you’d be surprised how easy it is to get a music writer to do a favor for you.

VASSALOTTI: We toured with Thurston Moore last year, and so many people were like, “Can you give them my band’s demo?” I’m sure they’ve heard that a hundred times a day, every day, for the last 30 years.

SYMONDS: Since you gave me permission half an hour ago, I actually do want to ask you—

VASSALOTTI: About Morrissey? [laughs]

SYMONDS: [laughs] No, not about Morrissey. “Do you guys also have a large teenage Latino fan base?”

HORN: We do. We for sure do.

SYMONDS: You do? I was not asking that for real. That’s awesome.

COX: We played in Mexico City and these two kids from Guadalajara drove four hours to see us, and they were waiting with our records so that we would sign them. We invited them in while we sound-checked, and then we did a really, really, really long sound check that took forever.

HORN: The longest, most painful ordeal. And it didn’t even sound good.

COX: And I can only imagine it sucked any minute percent of magic that they had, listening to our records, being like, “Wow, I get to see this band!” And then see us, like, “One, two,” totally failing at sound check. Well, there goes our Guadalajara fan base.

VASSALOTTI: But there were multiple people that night that said we had charisma.

COX: That’s like the most backhanded compliment. “You sound like shit.”

SYMONDS: Oh, I don’t think that’s true. I think charisma is a huge compliment.

COX: There’s an Italian band called Charisma that’s really sick. It’s just super-pouty. Like, “sex sex sex sex sex sex.” Early ’80s, late ’70s, super over the top. The cover’s just lipstick.

SYMONDS: No, I wanted to ask something provocative, since you asked me to. Will you guys tell me the worst thing you’ve ever done?

VASSALOTTI: To who?

COX: The worst thing I’ve ever done…?

SYMONDS: The thing you’d be most ashamed to tell your mom that you’ve done.

HORN: I’m really very open and honest with my mother. And sometimes she’s like, “Oh, my god, don’t say that.” I told my mom I did biker’s speed. I was like, “Yeah, I was real fucked up and I thought it was coke.” And she was like, “I don’t want to hear about it!”

SYMONDS: Yeah, that’s not a comforting phrase for a mom to hear: “I thought it was coke.”

COX: My mother is Glinda the Good Witch from The Wizard of Oz, so anything I tell her, she’s horrified. Like smoking cigarettes is like the worst fucking thing. The worst thing I’ve ever done? There’s a lot of shit that’s in the running.

VASSALOTTI: Started this band. [all laugh]

COX: One time I destroyed a house, with my friends in Sarasota.

VASSALOTTI: Yeah! Someone peed in a banjo.

COX: I had just started drinking. We were with a bunch of our friends on tour. One of the girls that lived there was somebody I was very, very casually hooking up with, and I had a very strange relationship to this girl. I think she was expecting my friends to be nice and pleasant. We were all drinking Four Loko—some of it has to do with Four Loko. We just destroyed a house. We ripped tons of books off the walls; people were peeing in books. My buddy lit a broom on fire and threw it across the room. He threw a keyboard. Someone peed in a Rollerblade.

VASSALOTTI: [laughs] There was a lot of peeing. Some of these people may or may not be members of popular New York bands.

COX: By the end of it, I was literally dragged out by my friends. And then afterwards, she was just like, “Yeah, that was really fun… I guess.” I apologized, but that’s not worth anything.

HORN: I feel like overall, I’m a pretty good, nice person. The only thing I’m ashamed of is, for a long time, I lied to my family and told them I was in college. [all laugh] For like, months and months. All that I was actually doing was getting high and drinking a lot. But I dropped out of school and they were still paying my rent at my apartment and everything. It got to the point where I had a really terrible nervous breakdown and had to move back in with my family, and they were like, “What are we going to do about your college classes?” And I had forgotten that I had lied to them about it, and I was like, “What the fuck are you talking about? I’m not in college. I’ve never been in college!” I had completely forgotten this elaborate lie I had been living for months and months.

COX: What’s your answer?

SYMONDS: Well, I kind of killed two birds with one stone once by—

BRADY: I killed a bunch of birds one time. I slaughtered a bunch of birds.

SYMONDS: How many birds are we talking? “A lot of birds” could be like five birds or 40 birds.

BRADY: No, I killed like a hundred birds. It’s the story behind my tattoo! When I was a child, I grew up in a town that’s famed to be the winter strawberry capital of the world. There was a huge migration of mockingbirds in Florida, and they were just destroying the strawberry field I lived next to. The game warden had come out—

COX: Ten-gallon hat, big chaps. “I’m the game warden!”

BRADY: He was! The birds were nesting on our property, and our tree line, and so the farmer came over and was like, “You gotta kill all these birds.”

HORN: “And we’ll leave it to the youngest one in the household, to become a man.”

BRADY: The farmers were like, “Okay, here’s a bunch of birdshot, have at it.” So it was just me and my brother, for like an hour. Pow, pow. And birds falling all over the place. It was disgusting.

AFTER THE END IS OUT NOW. FOR MORE ON MERCHANDISE, PLEASE VISIT THE BAND’S WEBSITE.