NOSTALGIA

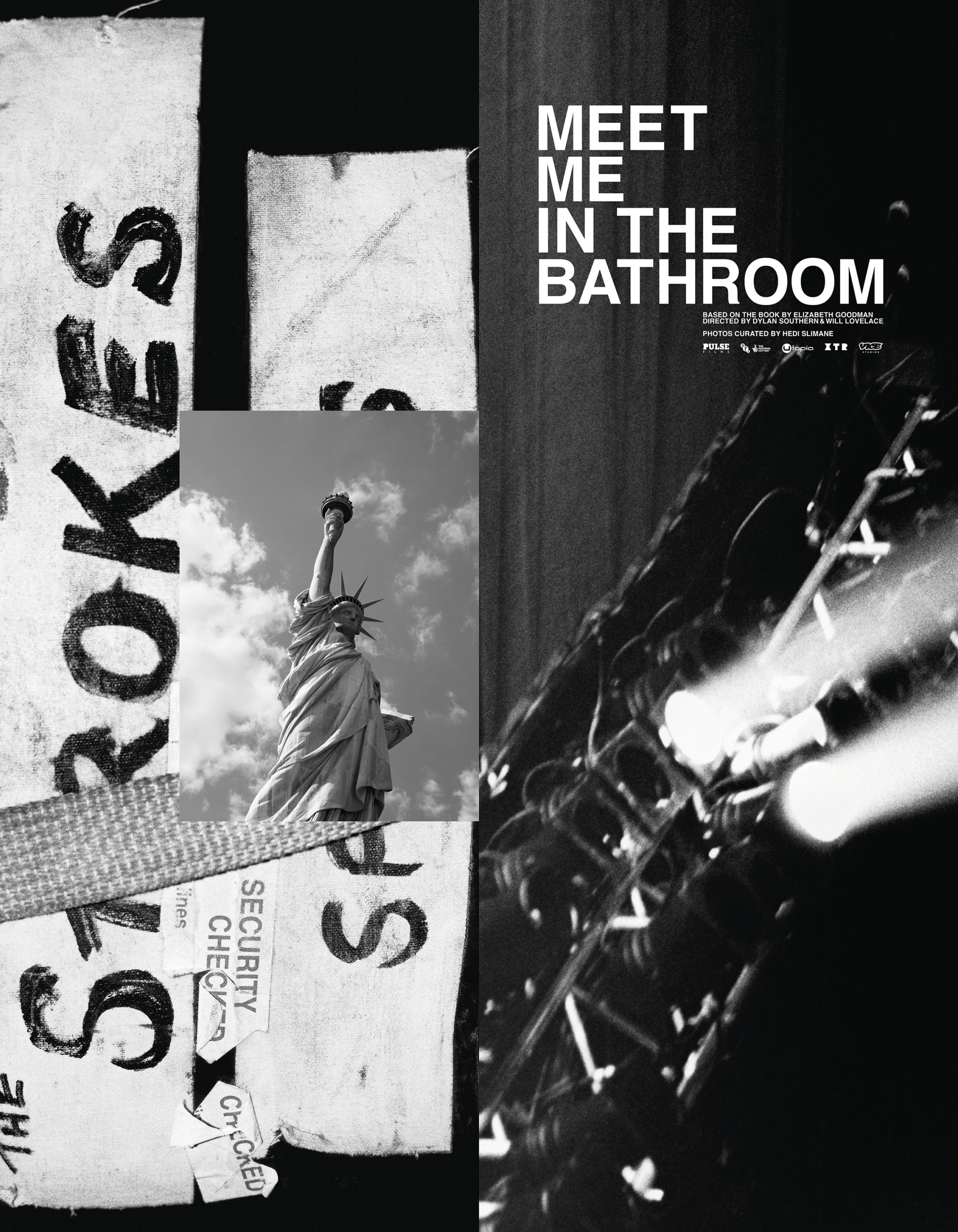

Meet Me in the Bathroom Is a Portal to the Early Aughts

———

LIZZY GOODMAN: Hi, guys. How’s everyone holding up?

WILL LOVELACE: We could just stare at each other for half an hour.

LIZZY GOODMAN: Late night last night, huh?

DYLAN SOUTHERN: Quite a night, yeah.

GOODMAN: I think we should start by talking about Dylan’s breakout moment as a kind of Ricki Lake emcee last night. Will, did you know about this side of Dylan?

LOVELACE: I wasn’t aware that he had talent. It’s good to see.

SOUTHERN: I’ve been observing people do it at film festivals, so—

GOODMAN: I feel like that was the highlight, really. It was really funny. For those of you reading who don’t know what we’re talking about, basically, we had the premiere of the film in LA last night, and as the first questions from the audience started to rise up, we realized there was no microphone for them. So Dylan just sprang into action and jumped off the stage and started walking around calling on people and passing the mic. It was pretty entertaining.

SOUTHERN: I can’t remember any of the questions from last night.

GOODMAN: We know that Sarah [Lewitinn, also known as Ultragrrrl] made us all pick between The Strokes and Interpol and everybody ducked that question.

GOODMAN: He did. Our moderator stepped in, like a ref, and was like, “Nope, this is out of bounds.”

SOUTHERN: It was helpful. Yeah.

LOVELACE: Lizzy, when you were writing the book, were you thinking this could be a documentary?

GOODMAN: Hell no. No way. When you’re in the weeds on a project, it’s just completely consuming. And that’s true in a 5,000-word magazine piece. I’m not really thinking about anything outside the world of that piece. Obviously, Meet Me in the Bathroom is pretty long and involved quite a few voices. Basically, you’re trying to get to the end of the project, so that you can survive that experience. You start with all this optimism and hope for the thing. And then midway through, you’re just like, “Oh, I think this is gonna ruin my life or kill me.” And by the end, you’re like, “Oh, my God, it didn’t.” And then after that, everything else is kind of extra. So no, it didn’t feel like that at the time. But again, not because it isn’t a great idea. I just wasn’t in that headspace. And obviously, if I had been, I would’ve made sure the sound quality on those recordings were better.

SOUTHERN: I like the quality of the recordings.

GOODMAN: I do too, actually. It’s cool. You guys did an amazing job weaving. I mean, we always said from the beginning that this is about dropping people into a moment in time and making it feel viscerally authentic. And those recordings are authentic.

SOUTHERN: Very authentic. With other films, there’s such an onus on everything sounding perfect and looking perfect. This one was so liberating because it could be raw, it could be kind of visceral. And the thing that surprised me is like, when we started filmmaking, we were shooting on those DV cameras, and we, like, detested the look of it. And we were very romantic about film and Super Eight and stuff like that. But now, 20 years later, you look at the DV footage, and it feels—

LOVELACE: I love the look of it, yeah.

SOUTHERN: It’s just that thing that time does. It’s so evocative of that period. It’s become something else now.

GOODMAN: You don’t realize this in the moment, which is part of the theme of the book, but when you’re living through something, you cannot understand it. It’s sort of like, “Hi, you don’t know this yet. But this will feel very nostalgic and will bring everyone right back to this exact place merely based on how it looks.” And that’s sort of impossible to convey at the time it’s happening.

SOUTHERN: When you started with the book, did you have any sort of guiding principles? Or did the shape of your story come as you were putting it together?

GOODMAN: That’s a really good question that I don’t think I’ve thought about in quite that way, at least in a while. A huge theme of the book and of this film is the idea that the firmament beneath your feet is disappearing as you stand on it. Everything that was is dissolving, and everything that’s going to be is not yet formed. I’m now mixing metaphors, but you get the idea. That feeling of anxiety, mixed with a coming-of-age story set against the backdrop of that anxiety, was very much in the first proposal. But it wasn’t as articulate at the beginning. I wasn’t like, “Human history and generational identity!” I was like, “Yo guys, The Strokes didn’t know they were going to be famous, but they kind of wanted to be.” I always tell this story about Ryan Gentles [longtime manager of The Strokes], he was the first person I went to after I sold the book. And I was like, “Hey, Ryan, I’m gonna write this book, it’s like Please Kill Me for our era.” Brian, my dear friend, is like, “That’s cool Lizzie, congrats.” And the next thing he said was, “Is anybody going to care though?” So this was by no means a foregone conclusion. And the book took seven years.

SOUTHERN: We had a problem that you didn’t have, because there was a film called Meet Me in the Bathroom. And it was a very good thing. And a lot of people loved it. But it was also a very long thing.

GOODMAN: We might as well get this in here, too. Dylan would like everyone to know that the audiobook version of Meet Me in the Bathroom is… what is it, Dylan?

SOUTHERN: 23 hours.

GOODMAN: There you go. And these gentlemen have compressed that story down.

LOVELACE: I suppose it depends how fast you read, though, doesn’t it? Have you read the audiobook?

GOODMAN: I have never listened to it. It’s a bit of a sore subject for me. What I really wanted was for them to get a cast of character actors, like 15 or 20 different voices, who could kind of just mix it up. But there was no budget for that, obviously. And again, no one knew that anyone would ever give a shit about this book to begin with.

SOUTHERN: I like it when it’s one narrator, but they do different voices.

GOODMAN: Yeah, that could have been fine. And instead, there’s one female voice and one male voice. So yeah, anyway, I don’t love that part of the audiobook, but people have listened to it and told me that they really got into the book through that means. So of course, I’m not going to knock it. But for me, it’s like a thing that got away that we could have done differently. And who knows, maybe we will some other time.

SOUTHERN: You have to deep fake it, you know. Get the actual voices.

GOODMAN: Are you pitching a new project to me? Because I accept.

SOUTHERN: Done.

GOODMAN: So, circling back to the idea that no one’s ever gonna care about this project, and there’s this interesting blanket of anonymity covering the reporting process. Like, I kept coming back to people for interviews, and they had never seen the results of those interviews, so it felt kind of private and safe. I think that was an advantage, for sure. But it was also a disadvantage in the sense that it took so long to get some people to be involved. And there are people that I still wish were in the book that never said yes. But you guys had the opposite problem. Everybody knows who’s in this world, what this project is, and has some sort of opinion about it: maybe regret, maybe enthusiasm, maybe a mix of both. How much of that was a factor for you?

LOVELACE: It sort of varied. The very first person we spoke to was Daniel Kessler, pre-COVID. And he was very supportive of the book. Lots of people were up for talking to us again. And I think other people felt that they said what they wanted to say in the book and didn’t want to revisit it. But really what we wanted to do, where possible, was find interviews from back then, and we’ve used lots of that stuff. But it was more people wanting to be supportive of the project and helping us out in that sense.

GOODMAN: Yeah. Less like, “We need you to say word for word, whatever you said in the book.” Because when you guys first came to me with this, we shared a vision about what a theoretical documentary about this would look like, this idea of really emphasizing archive. I actually just saw the Joan Didion exhibit here in LA at the Hammer Museum that Hilton Als did, and it’s really cool. And one of the things that’s cool about it and that’s made explicit in this exhibition is the sense of “collaginess” in her writing. Pulling little bites from all kinds of different places, cultural elements, or something pop cultural, or political or gruesome, violent acts in American history. These are all the major Didion beats, but also the emotional details, the super visceral details. What makes her writing so specific and unique is that sense of collage. Seeing that, and then seeing the movie for the first time, I was like, “Oh, yeah, that’s kind of what we talked about.” If you put all this shit together, you pull the right things from a bunch of different places, it will feel the way the place and time felt, because that’s how life actually works.

SOUTHERN: I think that’s what film does. We knew we couldn’t get all of the information in there, but we could get the feeling. We’re always approaching this like, “How’s it going to make people feel?” When you’re in the weeds, when you’re in the edit, and you’ve seen it 400 times, you’re like, “What even is this? I don’t know.” You just have no idea how it’s going to be received. But these last couple of weeks, seeing it with audiences, I’m hoping it’s achieved what we set out to do.

GOODMAN: I think so too. One of the moments where I felt that I came home a bit was showing up last night and seeing kids outside dressed like rock kids, like it’s Rocky Horror or something. I was walking to my car last night and there were these Gothed-out, adorable kids who are stoked and who look like they are expressing themselves in their clothes and their makeup, in conversation with this whole period of time. And that’s so fun.

SOUTHERN: It feels like a kind of shift. I went to see Pavement in London last week and I was expecting a bunch of bald, 40- to 50-year-olds in the crowd. But it was literally half 17- and 18-year-old kids. I don’t know if like, Pavement popped up on Tik Tok or something—

GOODMAN: [Laughs] Pavement and TikTok in the same sentence. Even putting those words together, this is quite a moment.

SOUTHERN: I was encouraged by that presence in the audience. It was kind of exciting. Nostalgic in a weird way.

GOODMAN: Right. But did it feel like it? Did it feel nostalgic?

SOUTHERN: It did for me, because I was a fan way back when, but did it for them? For the audience who are our age, it’s going to feel nostalgic. I’d love to speak to those kids who came to see it and get an idea of what it felt like and what it means to them.

GOODMAN: Right? Because the thing is nostalgia itself. I’m getting asked a lot, “Is there ever going to be a scene again? Is it all over? Is everything the worst now?” And you’re like, “Yes, and no.” I mean, that’s what I say. In every scene or moment in time, things coalesce and beauty is made, whether that’s in film or visual art or music for sure. It always happens in a unique way. You can look back and be like, “Oh, it’s this element plus this element plus this element.” And then it’s very natural and easy to then say, “See, if those ingredients aren’t in place, you’re fucked,” or, “It’s never gonna happen again.” Which I think is a mistake. When I heard The Clash for the first time, even though I couldn’t hear The Clash for the first time, does that mean my experience is somehow connected to nostalgia? No, it’s pure. One of the advantages of the sort of post-internet industrial age that we’re all suffering through at the moment is that those boundaries of feeling like something belongs to the past have softened, and there’s a lot that’s really distressing about that, but this is the good part, to me. Let me ask you this. Did you guys think it would make a good documentary? What struck you about it?

LOVELACE: Well, it reads like a documentary. What I loved about it is that there’s so many names, and most of them I knew, and some of them I didn’t know, and I found myself for the first few pages jumping back to the start. And suddenly, you’re kind of—

SOUTHERN: Transported.

LOVELACE: Exactly, yeah. And I felt that reading it straightaway. Dylan had read it before, and I felt that if we could capture that feeling in a film, then there’s something there, definitely.

SOUTHERN: There were points in the edit where we became convinced it would never make a documentary, because we found the archive and it was quite the process. So it was the first time we made a documentary that’s made in this way. There was a learning curve as well. You get periods that were quite fallow, like, “Well, we don’t have any material to tell this part of the story.” Using 100% the archive, you are kind of beholden to what is out there. So the most exciting parts were when something would turn up that we didn’t know existed. Suddenly, it’s like, “Okay, we’re back on.”

LOVELACE: You don’t know what’s there, or at least you don’t know half of what’s there. And so you’re led in directions you didn’t necessarily know. We’d that piece of archive that made the way we would tell that part of the story slightly different than we’d imagined, which was really exciting.

GOODMAN: I actually think that’s something we share in terms of our pain and suffering in these fucking projects. Oral history is a little easier in the following way. I would call a source and be like, “Did you happen to be at this show? Or do you know anyone who was?” And, in your case, you can’t do that in the same way. But the thing that it has in common is this need to fill the puzzle in while some of the pieces are still hidden. In fact, a lot of the pieces are still hidden. I couldn’t wait for all the interviews to come in to start trying to find a story. And in fact, some of the interviews I would need I wouldn’t know I needed until I started to assemble the story. You can’t be so wedded to your own narrative that you’re not allowing yourself to be flexible and informed by new information that comes in. But that is where the good stuff happens. In a lot of ways, the book itself is exactly what I wanted it to be. But in most cases, in ways I couldn’t have imagined. Like, it’s weird. Very weird. And what you’re saying just strikes me as the same experience.

SOUTHERN: Totally. And going back to what you were saying about the process of making it, at what stage are you able to, like, look at the book, and divorce the experience of making it from the thing that you made?

GOODMAN: I will let you know when that happens. You know, the film has really helped with that. The book never felt finished fully. Just ask my editor. They’re like, “You’re done. Now.” I was like, “But also do this, add one more, and hold on!” And they’re like trying to take it away from you. And they made me write my introduction, which I didn’t want to write.

SOUTHERN: I think it’s a Herzog quote. “A film is never finished. It’s just abandoned.”

GOODMAN: I always think of the SNL thing. “We don’t go on because the show is ready, we go on because it’s 11:35.” Deadlines matter. And when I saw the trailer you guys made back when we were pitching the documentary, I got really emotional. I felt the things people tell me they feel about this book. I felt connected to my youth in a certain way. In an objective way, I felt inspired by what these people on screen were living through and how moving it was. So thank you so much for spending a whole chunk of your life creating this thing to help me with my mental health issues.

SOUTHERN: Thank you for letting us.