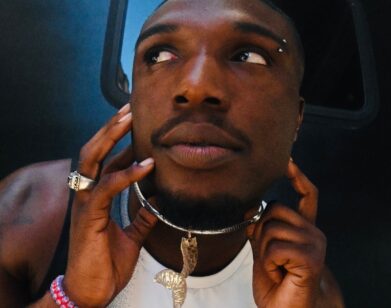

L.A. Salami

L.A. SALAMI IN BROOKLYN, MARCH 2017. PHOTOS: HANS NEUMANN. STYLING: ESTHER MATILLA. GROOMING: NATE ROSENKRANZ FOR HONEY ARTISTS USING TOUCHÉ ECLAT.

Lookman Adekunle Salami, who performs under the abbreviated name L.A. Salami, is a philosopher of sorts. Over the course of our recent conversation by phone, he mused on the “currents” of his creative output, the past versus the present, and the American Dream (often with a laugh). The 30-year-old London native has been making poetic folk music ever since his friend handed him a guitar in his early twenties, and describes his experience of sound as “layered,” with myriad artists having informed his outlook. Last month he released a five-track EP, L.A. Salami Presents Lookman & the Bootmakers (Sunday Best) and in August 2016 his debut LP, Dancing with Bad Grammar. At times earthy and at others biting, Salami has proven himself to be a clever, versatile author.

Today we announce that on Wednesday, July 26, Salami will perform in New York at Rockwood Music Hall. When it comes to playing live, he speaks of the importance of leaving space for improvisation. “It needs room for feeling, for air, for spontaneity, for what’s going on and how you feel at the time,” he explains. “There are no particular lead guitar parts, there’s a space for lead guitar.” Salami already has many a future record in mind, and remains at work as he plays at home and abroad.

HALEY WEISS: I’d be interested to hear what your mindset was going into this EP that you just released, L.A. Salami Presents Lookman & the Bootmakers.

LOOKMAN ADEKUNLE SALAMI: I can’t recall any particular mindset. I’ve got a bunch of projects, or chapters, if you like, and that’s one of the chapters that needs to be put out. It’s a warm-up to an album that will come out in the future called The Bootmakers and a bridge to that sound.

WEISS: Why do you want to work on this other project, or sound, in addition to the other music you’ve been releasing, like Dancing with Bad Grammar?

SALAMI: This isn’t another project, a separate entity. It’s like a different wave on the same river, or different currents on the same river. It’s all connected, so Dancing with Bad Grammar will lead, I think quite easily, into what I’m going to put out next.

WEISS: When you made Dancing with Bad Grammar was it an obvious set of songs or did you have a lot to choose from? What was that process like for you?

SALAMI: Well, the album, because it’s got to fit in a theme… It’s part of a collection of albums I wrote quite a while back. I had to stop myself from writing specific albums, because I wasn’t putting them out, so it was getting excruciating. I would group songs after a while; there were six that had a sort of frame, if you like, and certain songs that I had an idea of putting in there. But another song could replace one of the songs that was already in there, in terms of theme and mood and general color, if I thought it connected with what I was trying to put in the frame.

WEISS: Is there anyone in particular that once you put together a first sequence, you wanted to play the album for to get their feedback?

SALAMI: Not really. I usually go by own instinct, and then I share it with some friends. I have the most confidence in my bandmates, I think. They’re musicians I really respect.

WEISS: In terms of going with your instinct, has that always been your approach or was that a confidence you had to gain in yourself as a musician?

SALAMI: I think it’s because it’s something where I have the final say. I generally go by feeling, and feelings are hard to describe to people. You have to communicate if you’re a band, and I stumble around my words. It’s difficult sometimes, but when I can process things in my own way internally, and know for sure how it makes me feel, then it’s not a confidence thing. It’s maybe an anti-confidence thing, because other people could just soak in general feedback and go by the general consensus of what other people feel, which is a great metaphor for how we’ve progressed as a human species. [laughs] But at the same time, it’s a place where I get the final say. People are always going to have opinions, but when you feel something, you know that wholly and fully, and you’re the only one who can know that for sure.

WEISS: We premiered your video for “I Wear This Because Life is War!” last year. When you talked about it, you said that, “Time continues to be the most invisible, most valuable, most dangerous tool for doing this art thing!” and you were embracing VHS as your aesthetic. And thinking about a song like “Going as Mad As The Street Bins,” it does speak to this 21st-century sensation of overload, so I wonder if you’ve ever felt that you were born at the wrong time, or that you don’t fit well into the 21st century.

SALAMI: Yeah, I think a lot of people feel like that as well, but at the same time, by the very nature of being here, you’ve been born in the right time. Your feelings are the result of how you particularly process information that you’ve gained growing up and your particular filters, through pop culture and stuff, and what you categorize as important and what you categorize as not important. It’s a byproduct of all of that, having to feel that way. So you can feel you’ve been born in the wrong time, but you haven’t, put simply. [laughs] The past is terrible, it’s worse than it is now.

WEISS: We live in an easy time relative to the past.

SALAMI: Yes, our lives have evolved, so of course we field this information through TV and through the internet, and all of this terrible shit that’s going on, but you look outside, and I think we’re okay for the most part—[there’s] probably an existential crisis and that shit, but you’ve learnt to throw ideas around and perceive them really quickly, so we’re reacting to that. The past is more wholesome because they presented it as more wholesome, but there was more of a divide: women were seen as underclass citizens, black people were seen as second-class citizens or not citizens all. But the way they presented things is beautiful, appealing, wholesome, that it’s a more innocent time in the world. We should take that stuff now, and we can leave the bad stuff behind—take the good stuff and the idealistic stuff, like the American Dream, that was a great idea. It didn’t go anywhere, [laughs] or mean anything, but we can make it mean something now. Like, what is the American Dream? What could be the answer? Back then, it was capitalism—buy whatever you want—but now we know it’s not actually a good thing, it doesn’t work out, the American Dream. [We should want] people to be valued, rather than people to get on top; maybe everyone should be okay.

WEISS: Would you consider yourself an optimistic person? You sound like an optimist despite our problems.

SALAMI: Yes, I’m really optimistic. I’m an optimistic realist. I’m an optimist, but I do see what is covered in shit. [laughs] There’s a lot of dirt around, but you can clean it up, that’s the optimistic part of me.

WEISS: Have you listened back to your two original EPs, Another Shade of Blue and The Prelude, and if so, what do you think of them now?

SALAMI: Well, I don’t really listen to them much, but I remember them quite well, because The Prelude I’m still referencing, I’m still living in that world. The Prelude means the prelude to all the things that are to come, and The Prelude sound is a tiny fraction, it’s a little corner of the painting, if you like. Some of those songs, they’re from different periods—collections, like I was talking about earlier. Those songs are from different albums, for the most part, so they’re like puzzle pieces. In The Prelude, that’s not a connected puzzle, they’re just random pieces of the puzzle, but they happen to adhere to the sound of each other, so it works for that.

WEISS: If you see that as the corner of the painting, and you’re talking about all of these currents or albums and that you’re moving toward different sounds or chapters, do you have a vision of what the painting as a whole is? Or are you taking it step by step?

SALAMI: No, I’ve got a vision of the painting as a whole. It’s just I can’t put out everything at once; I’m not allowed. [laughs] I actually, for the next album, think I know which one I want to put out first. I did want to put out one before, but it’s a time thing, so I’ve got to decide which one. But either way, the painting, this painting anyway, I can see it, and I’m just working away at the others.

WEISS: It sounds like you’re pretty busy. You’ve released quite steadily, and if you’re plugging away at this ultimate masterpiece, it sounds like you have a lot of—

SALAMI: I don’t think it’s a masterpiece yet. I’ll let other people judge.

WEISS: It seems like you have a lot on your plate conceptually speaking; you’re trying to achieve a lot. Do you ever feel overwhelmed by the amount of ideas you have?

SALAMI: Oh, yeah. I’m going to have to sound pretentious. [laughs] There are a lot of times where I’ve written songs almost on autopilot, and I’m not connected with them at the time. Then I come back to them, and it’s a different thing. You don’t remember writing stuff because constantly you need to get to the other thing.

WEISS: Is writing a daily activity for you?

SALAMI: Yes. I forced myself to stop for a few months, because I do other things as well, but I find myself doing it anyway.

WEISS: I read that you didn’t own a guitar until you were 21. Is that true?

SALAMI: Yeah, my friend gave it to me.

WEISS: Were you pursuing music at all prior to that?

SALAMI: I was working in an underground film industry at the time, or film world, and I was trying to get my experience up in all the different departments. My friends gave me a guitar, and I’d always been making up songs in my head, just to do something as you’re walking—it’s fun to imagine being in a punk band or something—you catch a tune in your head, or you’re making up songs to things you’d be writing or films you’d been thinking of. Then when I got the guitar, I learned how to play it, I learned chords. I would write a song and whatever new chord I learned, I’d incorporate the chord into the song, and then I ended up writing songs. Then I thought, “These are good enough to perform,” and I did. It was terrible. [laughs] I got better.

WEISS: Was the live performance aspect of being a musician something that was difficult to adjust to?

SALAMI: Before that I’d been performing poetry anyway, so I had to get over that. I was performing poetry and then I started incorporating playing songs into it. It became more the music world thing rather than the poetry world thing. I remember forgetting words on stage for the first time and I thought, “Oh my god, I’m going to kill myself.” It was terrible. It was the most terrible bus ride home ever. [laughs]

WEISS: You talked about working in film a bit. Do you think that there are any films in particular or directors that influence your music?

SALAMI: Probably all of them.

WEISS: Do you have favorites?

SALAMI: When I was a kid it was Steven Spielberg, and then I got into Jean-Luc Godard, the Italian guys—Antonioni—and Persona [by Ingmar Bergman] was one of the most inspiring things I’ve ever seen. Film inspires poetry and all of that stuff; I think it went into the poetry more and through that, the music.

WEISS: What is it about folk music that you’ve been attracted to since the beginning? What is it about the genre that you find particularly vital?

SALAMI: It’s earth music, it feels like. Things that can be passed down tend to be quite pure and long-lasting, and they don’t abide by time; they’ve become immortal things, a thread through human consciousness, a thread through time. Stuff like that, it’s attractive.

L.A. SALAMI WILL PERFORM AT ROCKWOOD MUSIC HALL IN NEW YORK ON JULY 26, 2017. FOR MORE ON L.A. SALAMI, VISIT HIS WEBSITE.