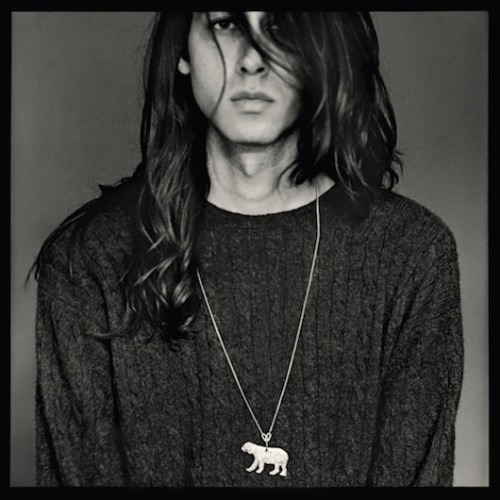

A Sense of Kindness

Few artists today have the capacity to leave their listeners both feeling fulfilled and wanting more. The debut album from musical act Kindness (aka Adam Bainbridge), World, You Need A Change Of Mind, takes a romantic stab at putting us bitter, disconnected social-media addicts back into affection rehab, and on the road to real intimacy recovery. Having grown up in London, with jaunts to Berlin, the somewhat reclusive Bainbridge has emerged with a clear perspective on compassion. Inspired by ’70s disco and dance music by Niles Rodgers, Giorgio Moroder and Afrika Bambaataa, what’s remarkable about Kindness is his willingness to share his unconventional romantic journey with music. With co-producer Philippe Zdar (Cassius) in tow, this album evidences a relationship that is truly genuine, open, unselfishly raw and unconditionally unyielding. Submit to Kindness, and let the superficial pass you by.

PAISLEY DALTON: Are you a recluse, or perhaps a social media-phobe?

ADAM BAINBRIDGE: It’s a question of is there a right time to talk and is there a wrong time. I really felt that having too many conversations at too early a point, when there was no music, would be a waste of time for everyone. That lead to me being pursued as a reclusive, and that’s not true! Some people think it’s aloof or this self-created mythology…

DALTON: But you have no Facebook, Twitter, or even a website!

BAINBRIDGE: I think those things are completely unnecessary. If people who feel similarly to me notice those things aren’t there smacking you around the face, perhaps they [will] appreciate being allowed the breathing space to discover things on their own, without being pre-packaged and [without] these preconceptions being delivered to you. A Facebook page is not a particularly attractive way of presenting any kind of information.

DALTON: Did you find space in Berlin?

BAINBRIDGE: It was breathing! I was there for three or four years continuously. Coming from more frenetic careerist cities, if you go [there] without any intention to succeed, it’s a great place to reset yourself. Berlin gave me the time to digest what I’d experienced in the previous ten years, understand what I like in culture and find a way to start expressing it myself. In cities where the constant obligation is to be involved, to be present, I don’t think you ever have that quiet focus time. The breathing space it allowed me ended up provoking all of this musical output. It didn’t feel obliged or forced. Sometimes people in London or New York feel they have one chance and have to max everything out in six months. That can be a very destructive impulse. By the time I left Berlin in 2009, it felt very swamped by bar hoppers and club crawlers. You’d hear English voices screaming from their windows all hours of the night. It started to infringe on that sense of, “Ah, I got away from it.” All of the sudden, I was hearing the same obnoxious, drunk lager louts in my street in Berlin as I might have done in London.

DALTON: Did that experience inspire your album title? Does the world need a change of mind?

BAINBRIDGE: [The album title] was a nod to both the musical heritage that comes from Eddie Kendricks and the old classics that would have been played at the Paradise Garage and Music Box. People who love those records will know that [Girl, You Need A Change Of Mind] was a key, old-school 12-inch. It’s important! And secondly, it seemed like a weighty and pretentious, but genuine and heartfelt title. If you’re going to go in there with pretension, at least be sincere about it.

DALTON: Is this album your passion or pain opus?

BAINBRIDGE: There’s a double-sided sense to a lot of the songs. They might be presented in a funky or danceable way, but they still contain something melancholic. When I wrote “House,” that was a genuine feeling [I had] at that moment in time… “We are all getting older.” There’s a deep-rooted desire to find companionship, and at times it can become the most overwhelming feeling in your life. If you’re really in that place, in that pit of despair, it’s a permanent feeling whether you’re in a relationship or not. “Anyone Can Fall In Love” is a cover, but I found the original lyrics charmingly pragmatic. There aren’t that many love songs that say, “Look: any old buffoon can walk into love, but actually maintaining it and keeping the relationship healthy is the hard part.” I’m sure there are a lot of country songs that say that, but I don’t listen to country.

DALTON: Do you believe in love?

BAINBRIDGE: I believe wholeheartedly in love! You’d be a fool not to. I approach a love song on an impressionistic level. It’s a feeling, but I’m not trying to dictate anything to anyone. I also subscribe to the idea that romance and relationships are incredibly complicated. There is no one paradigm of relationships that goes for everyone and it would be naive to look at love as something simplistic. The majority of people want companionship in one form or another, even if it’s just for one evening. The romantic impulse is maybe one of the most self-destructive. On the other hand, would you shut off that part of yourself? I’m not sure I would.

DALTON: Can one take fantastical lyrics in a song literally or should they remain aspirational?

BAINBRIDGE: [On] some of my favorite dance songs from the ’70s, there was still realism in what they were talking about. “Barely Breaking Even” or something like “Another Man” by Barbara Mason, these [songs] are expressing complicated, fairly brutal home truths from the singer’s/writer’s point of view, and yet they still work on a dance floor. I find that level of sophistication really interesting. The tougher, more street-influenced music from that era can be beautiful for how brutally it looks at life.

DALTON: Have we lost that sophistication in today’s pop music?

BAINBRIDGE: We reached a point in the mid ’80s, with people like Prince, who was working in a very gender-bender fashion, where you could approach a narrative and be ambiguous about the gender of the individual, about the nature of the relationship. You didn’t need to be overtly heterosexual. That opened a lot of doors for storytelling. Madonna worked very well at bringing those tensions into mainstream lyrics. We became more sophisticated as music listeners, and that was a positive moment. On the other hand, [today] we may have become too showy in our song lyrics. The Lady Gaga simplistic take on love, life, and acceptance is a positive statement, but it’s not very nuanced. There should still be people in pop music who want to express things about life and poverty and injustice and financial crises. How to do that? I can’t say. I’m not sure [that] I’ve managed to touch on any of these topics, but I’d like to. We’re getting to a place where people’s knowledge of music is so broad and well informed. Our generation has the potential to be truly ground-breaking in the way we synthesize everything that’s come before us. To create something truly original is another exponential step. For the time being, I don’t think that’s my roll. I’d rather approach my music on an instinctive level.

WORLD, YOU NEED A CHANGE OF MIND IS OUT NOW IN THE UK.