Jimmy Page and Scarlett Sabet Are the Music-Poetry Power Couple the World Didn’t Know It Needed

Scarlett Sabet’s poetry is felt three-fold when she performs it. The written words aren’t the same when she says them; they are trance-like, told as if from memory. To call the London-based talent a poet and performer seems inadequate. She’s more so a musician, or, perhaps, a mystic. Her haunting readings have taken place at storied book shops such as San Francisco’s City Lights and Shakespeare & Co. in Paris, and she’s been invited to read at the likes of Wellesley College. She has published four collections of poetry on her own imprint: Rocking Undergound, The Lock and The Key, Zoreh, and Camille earlier this year. Today, she debuts her spoken word album Catalyst, produced by her partner, the legendary musician Jimmy Page. Interview sat down with the couple to talk about coming together for this project, the brilliance of the Velvet Underground, and paying to produce your own work.

———

STEPHANIE LACAVA: You two met in 2012, but it was two years later that your relationship started and you first talked about collaborating together. It would be five more years before today’s release of your project on all streaming platforms. Why this album now?

JIMMY PAGE: One project that I knew it shouldn’t be was poetry with music. So with the production of Scarlett’s work, I wanted to create an individual character for each poem, a sonic landscape to compliment it.

LACAVA: And with all due respect, that was also a cool move. It would have been kind of eye-rolling to do music accompaniment.

SCARLETT SABET: Yes. It feels exciting, but also like a natural progression, I think, because we live and work together every day. Literally every one of these poems, Jimmy was there when I wrote it, and he was the first person that heard it and he’s seen me perform so many times.

PAGE: It was six years ago that I first heard Scarlett read.

SABET: At World’s End Bookshop on the King’s Road in Chelsea.

PAGE: I thought, “This is really interesting. She’s really interesting. She’s definitely got something there.” And the people in attendance soaked up Scarlett’s reading.

LACAVA: Surely, you’ve read a lot of crowds.

PAGE: That’s a good point. The whole place hushed. Rocking Underground was the first poem I heard of Scarlett’s and when we started production, we began with it.

LACAVA: I think people assume the title of the poem is a music reference, but it’s actually quite literal…

SABET: I was on a train. My computer had broken. It was just one of those, ugh, kind of despairing Sunday nights. I just remember there was a guy with a backpack in my face, and I got out my notebook, and there was the rhythm of train.

LACAVA: Do you usually listen to music while you write?

SABET: It’s got to be something that’s trance-like. I can understand why you’d listen to jazz, for example.

LACAVA: That’s a place where both of your practices kind of overlap.

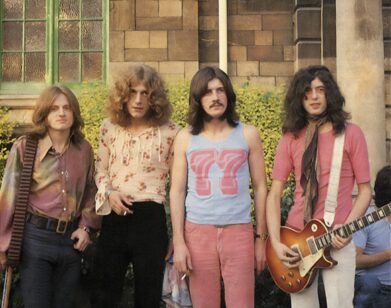

PAGE: Well, yeah. I did this interview with William Burroughs for Crawdaddy Magazine in 1975. We started to talk about trance music. I thought maybe he’d been to see Led Zeppelin on just one occasion. Actually, it was many times at Madison Square Garden. Anyway, we then started talking about this whole trance ethos, about the Master Musicians of Jajouka, this whole genre of tribal trance music from Morocco.

LACAVA: You learned about Jajouka from Brian Jones?

PAGE: Yes. To be fair, I know that Brion Gysin had introduced Brian Jones.

SABET: He was a painter and musician, Burroughs’s lover, and he came up with the cut-up technique with Burroughs.

LACAVA: Ah. What was your connection to Jones?

PAGE: I’d heard Elmore James songs (which Jones played a lot,) but I couldn’t quite work out how to play the music. People would say it was literally, from the neck of a bottle. I thought, ‘So, let’s see how this guy Jones does it.’ Sure enough, he gets up on stage and starts doing some Elmore James songs, and he has the equivalent of what everyone would know as a slide on his finger. I started talking to him when he came offstage, and I said, “Well you know, you’ve really got that down. What are you actually using?” You must understand that nobody that I knew played slide guitar at all. This is the first time I’d seen somebody do it—before Jeff [Beck] was doing it, before the Rolling Stones. So, he said, “Oh, have you got a car mechanic near you?” And I said, “I literally do have one not too far away.”‘ He said, “Go there and ask for a bush. It’s called a bush.” A thing used used in car maintenance. And he said, “You’ll find that it’ll just fit on your finger absolutely perfectly, and that’s what I use.” This guy was so generous.

LACAVA: Is there any young musician today who has really impressed you?

PAGE: Well, I was so impressed with the two guys that I saw with you.

LACAVA: Stefan Tcherepnin and Taketo Shimada, the New York-based Afuma.

SABET: They were so good. You said that was reminiscent of New York in the ’60s?

PAGE: Well, well, yeah. It was. It definitely had that sort of trance vibe.

LACAVA: Back to Scarlett’s start. You did your first reading at Shakespeare & Co. in Paris in January of 2015. Jimmy help set it up?

PAGE: So, when Sylvia (Whitman, owner and daughter of George Whitman) was giving me a tour after my own book signing, I saw the poetry section there, and I said, “Do you having readings here?” And she said, “Yes.” And I said, “Well, French as well as English?” “Oh, no. Only English.” And I thought, “I know a poet.”

LACAVA: It was Sylvia who introduced me to Scarlett years ago.

PAGE: After hosting Scarlett, Sylvia said to me, “It’s really powerful in print, but her renditions, they’re in another realm.”

LACAVA: So, Sylvia’s now the fourth person in this interview.

PAGE: That’s right. And something else funny happened when I was back at Shakespeare and Company. The man in charge of the rare book department said, “Oh, Sir, that Françoise Hardy track that you were on was absolutely amazing. That’s one of my favorite pieces of your guitar work.” I thought, “Well, wait a minute. I’m going to check, I’m going to track this down.” When I heard it, lo and behold, there’s this distortion box. It’s called a fuzz box. And I was the one who helped create this thing, and there it was on Francoise Hardy’s Je n’attends plus personne. I did it when I was a session musician. It was a session in Pye Studios at Marble Arch, downtown where all these Petula Clark hits were done. It wasn’t until you were in the studio that you’d see the artist come in. And you’d go, “Oh, I know who this is.” Or, “I don’t know who this is.” But when Francoise Hardy came in, I knew who she was. She had on one of those turtlenecks and that sort of tweedy skirt.

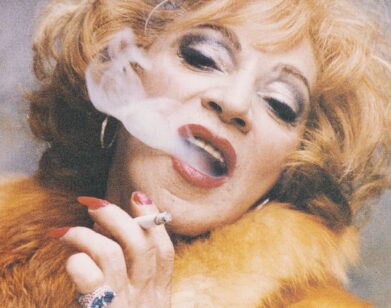

LACAVA: You also did some early sessions with Nico before she was part of the Velvet Underground.

PAGE: Nico came to London to record the Gordon Lightfoot song “I’m Not Sayin” with Andrew Oldham as a solo artist. So, there’s this huge orchestral session with Nico singing, and Andrew asked me to write a B-side with him for Nico, routine, play, and produce it on a separate session, which I did. It’s called The Last Mile. I was a staff producer on Immediate Records.

LACAVA: How old were you?

PAGE: 19 or 20. I was going to routine her at her apartment just near Baker Street in London with my acoustic 12-string guitar. Nico’s son with Alain Delon was there and he was holding up my guitar in the air, and I decided it was time to rescue it.

LACAVA: When did you see her again after that?

PAGE: Steve Paul’s Scene Club (Paul’s nightclub The Scene at 46th and Eighth Avenue) had been decorated by Andy Warhol. I don’t know what you’d call it here, but it’s this silver wrap—

LACAVA: Mylar.

PAGE: All the walls were covered with Mylar because Andy Warhol said that color was the color of speed. And playing down there was Nico and The Velvet Underground. I had an incredible connection with Lou Reed, and we spent lots of time talking.

SABET: Was that the first time you met him?

PAGE: Yeah, and I’d seen The Velvet Underground on more than one occasion. They were almost like a resident band. Andy Warhol was keen for them to be there. I can tell you exactly what it was like. When I heard the first album, it was just exactly what they were like. They were just like that. It was absolutely phenomenal.

LACAVA: See, that’s interesting in the context of his new project, as well. The difference between seeing someone in person versus the recording…

PAGE: The other thing about Steve Paul’s and The Velvet Underground was that it didn’t really have too many people coming to hear it, which I found extraordinary.

LACAVA: How many people were there?

PAGE: Well, hardly any people. Like, nine, a dozen people. It was so radical, such a radical band. You know, Maureen Tucker just playing the sort of snare drum. And the fact that there was the electric viola with John Cale. You just didn’t get this sort of line-up. It was really arts lab, as opposed to pop music, this wonderful glue, this synergy between them that was dark. It was very dark.

LACAVA: You mentioned Warhol. Do you remember seeing him there?

PAGE: No, he wasn’t actually there, but I met him with the Yardbirds. I don’t actually remember the hotel, but there was a reception for the Yardbirds. He came in, and he was with one other person. I was talking to him, and he said, ‘I just want to feel the band, feel the Yardbirds.’ “I want to feel their presence,” was the exact quote. We had a conversation and at the end of it he said, “You should come to the Factory, and do an audition.” But we were working, and I didn’t manage to do that. And then I saw him again in Detroit in ’67, when we were playing there. Andy Warhol was proceeding over this wedding, and The Velvet Underground were there. So, I got a chance to say hello again.

LACAVA: Something interesting that Scarlett told me once was that you steered her toward self-publishing. That legitimacy doesn’t come from a label—it comes from creating the thing you want to create.

PAGE: Yes.

LACAVA: You could have told her the opposite, based on your experience.

SABET: Jimmy was like, “Well, look. The first Led Zeppelin album, I paid for that.”

LACAVA: You produced and paid for it?

PAGE: Yes.

SABET: They had a record. He then took it to record companies. He took it to Atlantic and said, “This is what we’ve got. I’m not releasing singles. Take it or leave it.” He literally said the words, “I didn’t want to go around cap in hand saying, ‘Oh please. We’d like to write some songs.’ It’s better to do it.”

PAGE: What I’ve been producing over the last few years are Led Zeppelin rereleases and catalog items. It means a lot of listening to quarter-inch tapes, and it’s all in real time. I had to approach this project in such a way that the first album speaks for itself. The last and ninth album of the studio albums were Coda, so on every album in between, I had to make sure all of these companion discs were done and present the idea to the record company along with new artwork—that way to ensure the complete vision of the recordings were released.

SABET: With the sound engineer, Drew, Jimmy would explain how he wanted to kind of layer some of my voices. And I practiced some on cassette, so it was like a guiding track, and then I’d listen back, and I understood the timing and what we were going to do for each one. If there was a sound or there was a better take, we’d talk about that.

PAGE: The first one that I wanted to try was Rocking Underground, which opens up the whole of this work. It was recorded on a cassette tape. It was so noisy, but urgent. I said, this is what we’re going to use, but then it needed some extra work to be done to augment the base layer—

LACAVA: Oh, that’s cool!

PAGE: So, it opens, and it’s really disturbing, all this ambient noise. And I know we pulled it off. Because there’s such a variety on it, and it will be such a surprise. It’s the sort of thing that you listen to for, say, Side One, from beginning to end. The whole sequencing is there for a reason.

LACAVA: We’re living in an age of the ubiquitous podcast. Everyone has those things in her ears.