Jack White

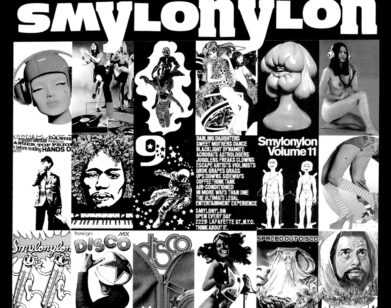

Were he born a little bit earlier and a little bit farther south, Jack White might very well have been a candidate for inclusion on one of those Smithsonian musical anthologies: a pallid, Depression-era troubadour whose soul-and-salvation-searching songs exist only via scratchy field recordings on battered old 78s. As it is, White was born John Gillis in Detroit in the 1970s, just after Motown hit its stride and a swarm of incendiary rock acts like MC5 and Iggy and The Stooges raged out of the Motor City—which, at the time, was every bit as desolate and malevolent as the impoverished American sprawl of the early folkies and bluesmen. But the mode of deliverance through which he has chosen to channel his pent-up rage and struggles with inchoate spirits is both decidedly louder and more popular. White’s is an oeuvre built around strains of blues, folk, and countrified American music reanimated with the furiousness of ’60s rock and early punk, and shrouded in a fog of arch Pop-art conceits, color schemes, and mythmaking gambits, which has unofficially anointed him keeper of the flame for a certain kind of rock ‘n’ roll that rebuffs nostalgia but reveres the past. He is a man of many moods and of many bands: from the warped, dirty dirge of The White Stripes, the red-, white-, and black-clad, faux brother-sister duo that he formed with his first ex-wife, Meg White, and the act that made him famous; to the country-and-blues-inflected shimmy of his garage-rock outfit The Raconteurs; to the angular riffage of The Dead Weather, for which he pulls double duty as singing drummer. White has a work ethic that also seems to belong to a bygone era. In addition to his own work, he has had a hand in producing a seemingly nonstop stream of albums, tracks, and one-offs with an eclectic group of coconspirators that includes Wanda Jackson, Loretta Lynn, Alicia Keys, and Danger Mouse. White even has his own label, Third Man Records, which he operates out of a building in his adopted hometown of Nashville, Tennessee, that houses a store, a studio, and a performance space, and which, in addition to White’s musical endeavors, has put out singles and albums by other artists ranging from the Swedish folkies First Aid Kit, to Welsh crooner Tom Jones, and conceptual composer John Boswell, issuing all of them on vinyl. (The not-so-divine inspiration for the name was a one-man operation called Third Man Upholstery that White started in Detroit in the mid-’90s. Slogan: Your furniture’s not dead.)

White’s latest album, Blunderbuss, released in April on Third Man Records, marks a turning point of sorts, coming on the heels of a year in which both his 14-year run with The White Stripes and his six-year marriage to his now second ex-wife, the model and singer Karen Elson, came to their respective ends. (The official parting of The Stripes, whose last record was 2007’s Icky Thump and who hadn’t performed together since 2009, was announced in February 2011 with a message on the band’s website; the news of White and Elson’s split was issued via a press release that revealed that the parting couple intended to commemorate their separation with a “divorce party” for their close friends and family—which, as the invitation promised, was to feature “dancing, photos, memories, and drinks with alcohol in them.”) Recorded in Nashville, where White has lived since 2005, Blunderbuss swirls with dark emotions-and, like White’s best work, is at once earthy and ethereal, guttural and redemptive. It is also the first full-length that White has played on that is credited solely to Jack White, and arrives with a new color scheme consisting of the primarily blueish hues featured in its artwork and in the clothes worn by the two full bands—one all-male, one all-female—that White is taking on tour with him this spring and summer.

While White’s musical interests venture deep down into the loamy soil of American culture, his curiosity has also drawn him in the opposite direction-chiefly, toward outer space. When we were discussing who would interview White for this story, he asked if the questioning duties could be handled by former astronaut Buzz Aldrin, who, along with Neil Armstrong and Michael Collins, was part of the 1969 Apollo 11 lunar mission that saw Armstrong and Aldrin become the first and second people to walk on the moon. We put the request to Aldrin, and to everyone’s surprise and delight, he graciously obliged. Interview contributing music editor Dimitri Ehrlich and the 82-year-old Aldrin caught up with White, 36, in Memphis, where he was preparing to play a show that evening.

I think that sometimes love gets in the way of itself-you know, love interrupts itself… We want things so much that we sabotage them.Jack White

DIMITRI EHRLICH: I think we just got Buzz. Buzz, are you there?

BUZZ ALDRIN: Yeah, I’m here.

JACK WHITE: Buzz, this is Jack. How you doing?

ALDRIN: Couldn’t be better. It’s a busy time of year. I’m supposed to borrow somebody’s Bentley and go on up to West Point to have this room dedicated in my honor.

WHITE: At West Point?

ALDRIN: Yeah. They’ve got a hotel up there and they’re gonna put a plaque with my name on one of the rooms, so you can come up there and see a lot of pictures of me inside this room.

WHITE: I might have to stay in the Buzz Aldrin room.

ALDRIN: It’s gonna be there for a while—I hope. They might tear it down eventually and put up the name of somebody else who has been to Venus or Mercury. You’re in Memphis?

WHITE: Yeah, we’re playing here tonight. Where are you, Buzz?

ALDRIN: I’m in Los Angeles, in Century City. We’re occupying a temporary residence . . . I filed for divorce back in June. You don’t know about things like that, do you?

WHITE: [laughs] No, I’m not familiar.

ALDRIN: Anyway, I got a sweet young lady keeping me company.

EHRLICH: You live in Nashville now, don’t you, Jack?

WHITE: Yeah. I grew up in Detroit, but I’ve been living in Nashville for the last six or seven years.

ALDRIN: I understand that Detroit was a pretty rough place to grow up in the ’70s and ’80s.

WHITE: It was, man. But it’s got a stiff upper lip, that town.

ALDRIN: You get beat up? Mugged? Threatened?

WHITE: [laughs] Not too much. You know, I think you learn how to walk down the street in a certain way. I think you just learn to have a way about yourself, a style of walking down the street, that keeps people away from you.

EHRLICH: Did you actually grow up in the City of Detroit or in the suburbs?

WHITE: I grew up in the city. I don’t think there have been too many musicians who have made it out into the mainstream who are actually from the inner city of Detroit—except for the Motown artists, really.

EHRLICH: Did you grow up in the Cass Corridor?

WHITE: Yeah, close to the Cass Corridor, in southwest Detroit.

ALDRIN: I grew up in New Jersey, but it turns out I’ve been in California half of my life now.

WHITE: Really? You can’t resist the weather out there.

ALDRIN: It’s pretty good. But I travel quite a bit.

Ehrlich: Before we get too far, I had a quick question about space travel. I just got back from Thailand, and I’m really jet-lagged, and I’m sure Jack deals with that all of the time because of all of the traveling he does. But if you travel to the moon, Buzz, is there any sort of jet lag that you experience when you come back to Earth? Or is it not even an issue because you’re traveling so far beyond all the time zones?

ALDRIN: Well, we didn’t really have jet lag in the same way. We all wore watches and stayed on Houston time while we were gone so that we would be in sync with the mission crews and the flight crews controlling the mission. Of course, when we came back, we’d been away for eight days in reduced gravity or floating in zero gravity with the spacecraft going and coming, and it takes a while to get used to gravity again. We had to get our land legs—kind of like a sailor who has been rolling around on the ocean has to do. You feel like you’re really heavy for a day or so after you get back. All of that, of course, was overshadowed by the success that we had on the mission. But after we got back, we went on a tour of the world for 45 days, visiting kings and queens and all that. On that trip, there was jet lag.

WHITE: I can’t imagine the courage that it took to get in that tin can and travel to the moon like you did. I often think about Michael Collins. You guys decided that he was going to stay in the capsule and orbit the moon while you and Neil Armstrong went down to the surface, is that right?

ALDRIN: Yeah. Michael was satisfied just to be a part of the historic first landing. He had to do a lot of critical things to bring us back. All we needed to do was fire up the engine and then find Michael in orbit. I’m sure that if he’d stayed around, he could have been on the last landing that went there . . . He’s hard to get hold of these days. He’s out fishing all the time.

WHITE: I’ve always thought about you guys walking on the moon and Collins up in that capsule by himself—two very lonely scenarios. But at the same time, you had so much work to do, so maybe you couldn’t really have a fear of being by yourself so far away. Would you say that was true?

ALDRIN: That, and also, when I was a kid, President Roosevelt said, “The only thing to fear is fear itself.”

WHITE: But the three of you trained for that mission for such a long period of time. Did you feel confident when you got in the capsule and prepared for takeoff? Or was it like, “Wow . . . Anything could wrong at any moment”?

ALDRIN: There were a lot of things that could have gone wrong that would have prevented us from successfully carrying out the mission, which was to land on the moon. But we figured that we had about a 60 percent chance of successfully landing, and even if we had to turn back without landing, I think we figured that we had a 90 percent chance of coming back alive-which is not bad, actually. We had to have Apollo 13 turn around and come back, and everybody helped them out, and we brought them all back safely. We got 24 people to the moon and 18 of us are still alive. I think that I just had the great fortune to come along at a really eventful time in the history of our country. My mother was born when the Wright Brothers flew their airplanes. My father was an early aviation pioneer. I was a teenager when World War II was going on, and I fought in the Korean War, and then got into the space program and was able to carry out the country’s commitment to land on the moon. Now I’m trying to put America at the forefront in establishing a permanent human presence on another planet. So I have to say, Jack, it’s been a pretty remarkable time to be alive.

WHITE: Carl Sagan once said something similar: that it’s a beautiful moment in human history when we’re actually talking about visiting other worlds.

ALDRIN: I noticed that you did something with Carl Sagan and Stephen Hawking, is that right?

WHITE: Yeah. We put out a record on Third Man [a seven-inch of composer John Boswell’s “A Glorious Dawn,” which features spoken-word portions by both Sagan and Hawking]. That’s one of the records that I’m proudest of having released. Carl Sagan was a huge influence . . . We have a secret project at Third Man where we want to have the first vinyl record played in outer space. We want to launch a balloon that carries a vinyl record player, and possibly that Carl Sagan record, and figure out a way to drop the needle with all that turbulence up there and ensure that it will still play.

ALDRIN: There’s no turbulence up there if you get up high enough. But I know the guy who is CEO of Richard Branson’s Virgin Galactic. Maybe you should talk to him. Richard is always interested in doing unusual things.

EHRLICH: I guess one problem would be if you got so high that there wasn’t gravity to get the needle to fall on the record. You’d have to account for the lack of gravity if you went really out there.

ALDRIN: Somebody invented something years ago called a spring, and I think you could probably use a spring to get the needle to come down how you wanted it to. But that’s just engineering. That’s not a musical problem—just leave that to the engineers . . . You know, I failed music when I was a teenager. I tried to learn how to play the clarinet, but I can’t carry a tune very well, so there you

EHRLICH: Buzz, what kind of music did you listen to when you were younger?

ALDRIN: Well, I wasn’t a bobby-soxer, but I guess I reminisce about Frankie Boy-Frank Sinatra. Although, I liked Karen Carpenter, too.

WHITE: Karen Carpenter was great. A lot of people don’t remember that she was a drummer.

ALDRIN: A drummer?

WHITE: Yeah, she was the drummer in The Carpenters for the first few years. She sang from behind the drum kit. A lot of people don’t know that.

EHRLICH: Buzz, how familiar were you with Jack’s music before we asked you to do this interview?

ALDRIN: I have to tell you, before this interview, not very. The closest I ever came to a Jack White was a Jack Waite I used to know who was a rep for North American Aviation. He was married to a gorgeous gal. I also used to know a Ralph White—he died recently, but he dove down to the Titanic in Russian submersibles. I had lunch with him once, and he said that he spent more time on the Titanic than the captain did. [Ehrlich and White laugh] That’s a joke. [Aldrin laughs] But Jack, now that I am familiar with your work, I do have some questions for you. I know that your new album is called Blunderbuss. Tell me about that a little bit.

WHITE: Well, I’ve always loved the word blunderbuss. I’ve always thought that it was a beautiful word and that it could mean several different things.

ALDRIN: A blunderbuss is a kind of gun—the kind that can blow your head off.

WHITE: [laughs] Exactly. I was hoping maybe that some of these songs might blow people’s minds, too.

ALDRIN: You have a song on the album called “Love Interruption”? What’s that about?

WHITE: Well, as a songwriter, it’s really dangerous to use the word love in a song. It’s a word that has been used in songs so many millions of times before, and it’s the most popular topic to ever write about. So I thought that if I was going to be brave enough to actually use the word love in a song, I better be trying to make people think about it—and make myself think about it. I really wanted to stir up the notion of what love could mean, and what we really want when we say that word. It’s a very powerful word.

ALDRIN: When love is interrupted, doesn’t that mean you’ve been jilted?

WHITE: I think so, yeah. I think that sometimes love gets in the way of itself—you know, love interrupts itself. We want things so much that we sabotage them.

ALDRIN: I know that you had a long period of success with The White Stripes. Why did you break up that band?

WHITE: That’s uh . . . That’s a good question. [laughs] I ask myself that all the time. Sometimes things last for a finite period, and I just didn’t feel like it was the right thing to keep playing anymore, so we had to put a stop to it. But also, I didn’t want to go out and make solo records if The White Stripes still existed. I thought that people would be too confused by the two ideas and a lot of people wouldn’t be able to get their head around it. So, in a sense, it was something that was bound to happen one day. But I’m sad about it all the time.

ALDRIN: Who is this lady called Meg?

WHITE: I ask myself that question all the time as well. [White and Ehrlich laugh]

ALDRIN: I understand that back in the White Stripes days, you and Meg played a concert that was just one note. Is that right?

WHITE: Well, we’d done this whole tour of Canada where we played in every province, and almost every day we would do a free show. I would decide each morning what kind of show we would do. For example, in Winnipeg, I said, “Let’s play on a city bus today. We’ll get on a bus and play a couple songs.” So when we were in Newfoundland, the idea that I came up with at breakfast was, “Let’s play one note today. So we’ll put on a show and tell people it’s a free show, but we’re only going to play one note.” I told Meg as we were getting out of the car. I said, “Make sure you grab your cymbal—when you hit the cymbal, grab it so that the note only lasts a millisecond.” I was thinking that afterwards we could contact the Guinness World Records people and see if we could get the record for shortest concert of all time. So we did it, but ultimately they turned us down. They would not give us the record for the shortest concert.

EHRLICH: Why? Did someone else have a shorter concert than that? John Cage might have for his four minutes and 33 seconds of silence.

ALDRIN: See, I think that the way you get that record is that you just don’t show up.

WHITE: I like that-just don’t show up. [laughs] The thing is, though, that the Guinness book is a very elitist organization. There’s nothing scientific about what they do. They just have an office full of people who decide what is a record and what isn’t. I mean, there is some stuff like Olympic records where they have a committee. But most of the records in there-who has the biggest collection of salt-and-pepper shakers or whatever-are just whatever they want them to be. So with something like the shortest concert of all time, they didn’t think whatever we did was interesting enough to make it a record. I don’t know why they get to decide that, but, you know, they own the book . . . Maybe this will help us get the word out.

ALDRIN: So after you tossed out The White Stripes you formed The Raconteurs?

WHITE: Well, both bands existed at the same time.

ALDRIN: And then you have a third band, The Dead Weather. What’s that supposed to mean?

WHITE: Maybe it’s that vibe that you had on the moon. We wanted to pick a name for that band that conveyed a mood to people, and we thought The Dead Weather kind of felt like what we were imagining—a sort of a moment when there is no wind and no sunshine, where you can’t feel any weather at all, and you’re wondering what the next moment might feel like when the weather changes.

ALDRIN: Karen Carpenter said, “Rainy days and Mondays always get me down.”

WHITE: Well, when you’re living in California, you don’t have to worry about the weather.

EHRLICH: So you’ve played in all these bands, and you’ve also collaborated with a bunch of different people. What do you get out of these different kinds of creative interactions?

WHITE: For some reason, I don’t like the word collaboration. It makes me think of some silly compilation tribute album for sale at a bookstore. When I produce someone’s recordings, that’s all it is: I’m producing. When I’m in a band like The Dead Weather, I’m not “collaborating”—I’m in a band with other people. When I wrote with Danger Mouse on the Rome record, that would be a collaboration—people writing together for a reason but who aren’t in a band together. I don’t really write with people that I produce. I have to feel like I can add something to the mix, bring something out of an artist by working on the record. Sometimes I turn down working with people I’ve loved since childhood because I can’t find my place in the production.

EHRLICH: Do you find anything liberating—or constraining—about working on your own now?

WHITE: I’ve finally allowed myself the ability to orchestrate other musicians—sometimes up to a dozen at a time—with ideas. When you’re in a band, you don’t really walk around telling people what to play. Now I can construct each note and harmony exactly how I imagine it without the worry that someone is going to label me controlling, egotistical, or something just because I’m asking him to play an F-flat. I’ve kept my mouth shut for ridiculous reasons like that for far too long. The music is in charge, not the producer.

ALDRIN: Jack, you know, I read in Rolling Stone that you ranked number 17 out of the 100 greatest guitarists of all time. That’s quite an accomplishment.

WHITE: Thank you.

ALDRIN: But tell me: Why do you think you didn’t rank a little closer to the top?

WHITE: I thought for sure I was going to be No. 15. But you know how it goes . . . Maybe it’s politics.

ALDRIN: Well, I’m going to be No. 2 on the moon for the rest of my life, so I know how you feel. [White laughs] I’ve also read that you refer to your guitars as girlfriends. Why is that?

WHITE: You know, I really think that all relationships that are beautiful and lasting are a struggle. I think when things are too easy, it’s harder to appreciate the beauty, and it’s the same thing with the guitar. I mean, they’re also this inanimate object that I take on stage. It’s just a tool in one sense, but I’m trying to make friends with it, and I struggle with it. I really need to sort of identify with it as a sort of personality at the same time.

EHRLICH: Do your girlfriends mind when you refer to the guitars as girlfriends?

WHITE: Yes, I guess so . . .

ALDRIN: Guitars don’t talk back to you, though. Or do they talk back all the time?

WHITE: Both. [laughs]

ALDRIN: What does the number 3 mean to you, Jack?

WHITE: It sort of means perfection to me. I think there is some mathematical beauty to it, where it means one too many in mathematics. And I think that in art, it keeps me confined at all times. I need to confine myself in order to create things, so I try to base most of the things that I do off of that number, even in secretive ways and ways that people would never notice. But I have to have that in order to create things—that number around me.

ALDRIN: You know what’s interesting? You musician guys count up, “One, two, three . . . ,” but we rocket guys count down, “Three, two, one . . .“

WHITE: You and I should go on tour together, Buzz. We should do a two-man act.

ALDRIN: You can say that again. [all laugh]

WHITE: I did want to ask you something, Buzz, that I’ve often wondered about. What did the moon feel like to you? Did it feel like it was alive? I think, to most people, the moon seems like a dead rock in the sky.

ALDRIN: It was one of those things where you could just look out and think that nothing had changed in what you were looking at in hundreds of thousands of years—just a lot of little meteorites adding more dust. I use the words magnificent desolation to describe it—it was magnificent because of the human achievement to be able to go there, but it was just such a desolate, lifeless place with no air, very hot when the sun is high up, and then very cold when it’s nighttime . . . I wish I could tell you that the face on the moon was winking and blinking, but it’s about as dead as things get . . . It’s not a good place to set up housekeeping. We’ll let the Chinese do that. [all laugh]

WHITE: Well, I’ve always been fascinated by what you’ve done for humanity. I also write a lot about the moon—I even wrote a song about it on this new record. So it was important for me to speak to somebody who has actually been there.

ALDRIN: As far as space travel goes, I’ve been focused more lately on the steps that we need to take in order to mine the moon for water and convert it into hydrogen, oxygen, rocket fuel. If we do that commercially, then I think that we ought to be able to set up a permanent growing colony on Mars within 25 to 30 years. Would you want to visit Mars, Jack? Would that interest you?

WHITE: I read somewhere that they think there might be ice or water under the topsoil on Mars.

ALDRIN: Yeah, supposedly there was an ocean there billions of years ago—at least that’s what we’re hoping we’ll discover because it means that there might have been some kind of life. But if you want to go to Mars, then you’ve got to realize that we’re not going to be bringing people back. When people start traveling there, they’re going to have to spend the rest of their lives there.

EHRLICH: It’ll be a one-way ticket, so going there will be a big decision.

ALDRIN: They won’t call it “one-way”—they’ll call it a “second habitat for Earthlings.” Human Martians is a term I’m using. So where do you hang out when you’re not on tour, Jack?

WHITE: Well, I have two kids now, so I spend a lot of time with them. So there’s that. And then I really like to hear other people play music, so I try to get involved with listening to other people play and working on music with other people. I’m kind of obsessed with music, so it takes up most of my time.

ALDRIN: Have you ever been to The Blues Ball there in Memphis?

WHITE: No, I haven’t. But the last time I was here, I finally got to Graceland. I had never been to Elvis’s house, so I finally got to do that.

ALDRIN: My goodness—that’s like me. I grew up in New Jersey and never went up the Statue of Liberty. I was just in Paris, though, and my lady and I went up to watch the full moon from the top of the Eiffel Tower.

WHITE: Wow. That sounds beautiful.

ALDRIN: Well, there were a lot of lights. It was a beautiful night. When you come out to Los Angeles, we’ll have a full-moon party—whether it’s a full moon or not.

WHITE: That would be amazing.

EHRLICH: Buzz, you said you were going to take a Bentley to West Point, but you’re not driving the Bentley from California, are you?

ALDRIN: No, I’m going to borrow a Bentley from a car dealer in New Jersey and drive up from there. What do you drive, Jack?

WHITE: I have a 1960 Thunderbird that I dusted off and a Mercedes S-55. It’s got about 500 horsepower.

ALDRIN: I had a Mercedes 560 SL.

WHITE: Those are nice.

ALDRIN: Yeah, it was nice. Red. Unfortunately, though, it’s in the condominium that my ex-wife is in now.

WHITE: If you want me to help you sneak in there and repossess it, I’d be in for that.

ALDRIN: You’re on, Jack. You’re on.