SUMMIT

Inside Artist Ryan Trecartin’s Aspen Art Week Ensemble

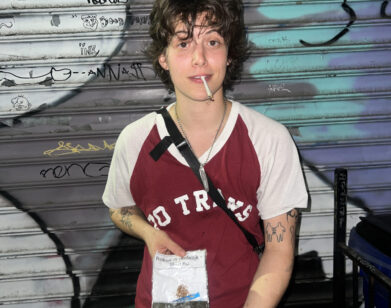

In the liner notes for the concert AUDIENCE PLANT 2024, artist and musician Ryan Trecartin asked his accompanying musicians to play in a spirit ranging from “hot dog salad” and “because I’m pretty” to “fuck off, join us, we’re fun.” Organized by the Aspen Art Museum, Trecartin was joined by his trusted band of collaborators—including artists and musicians Lizzie Fitch, Ashland Mines, Aaron David Ross, and Michael Beharie—amongst a wider group of guest musicians. The performance, which premiered atop Aspen Mountain at dusk last month, featured a newly composed score of electronic and orchestral music interspersed with jazz improvisations. The resounding climax of sound flowed from the tower from which the musicians played, which Trecartin described as a visual manifestation of musical stems. The project was first teased in 2016 when artist, jazz pianist and composer Jason Moran invited the group to collaborate with him during his residency at The Park Avenue Armory in New York and was further developed for The Last Jazz performance at the Walker Art Center in 2021. Moran surprised the group in Aspen and played with them for the entire set. In their first group call post-plant, we spoke with Trecartin and Co., plus curators Daniel Merritt and Eliza Ryan, about the ecstatic experience of hearing the show live for the first time.

———

SAM OZER: How’s everyone feeling post-plant?

RYAN TRECARTIN: So fun.

AARON DAVID ROSS: So good.

ASHLAND MINES: Yesterday, Aaron sent his mix of the live show. It was inevitable from how we designed the stage that we didn’t hear it at all, so it was only now that we had the full experience. We feel fucking fab about it right now.

MICHAEL BEHARIE: 100%.

ELIZA RYAN: You guys just had to trust what was going out into the audience.

OZER: From the audience, the stage is theatrical but also feels very inner circle. I can imagine there being a silo of sound.

TRECARTIN: Yeah, that second level was cozy. We were just hanging out and laughing the whole time and playing. It was so funny. I’m not as good at sounding out, so I’d walk over to Jason [Moran] and ask, “Wait, what are the notes being played?” He’d be like, “Look, it’s mostly these…”

MINES: Just to gush a little bit, it was really, really fun. My favorite part of the performance was how Ryan and I accidentally faced each other to be on the same level and physically fit all the equipment on the platform. Ryan, I don’t think you ever had an experience where your work was performed to you or with you. Getting to watch you experience your work with an orchestra performing your pieces was so beautiful to watch. The way you were just so happy, it was too much. I actually couldn’t take it.

RYAN: The joy of you guys performing together was palpable from the audience.

OZER: Can you talk about the stage design?

TRECARTIN: When Lizzie, Ashland, and I were working on the project at the Walker [Art Center] with Jason [Moran], we kept texting each other videos of people referencing jazz and TV shows and sort of the way jazz is used as a prop or a punchline. We were also talking about prepping culture and end-of-the-world stuff. I don’t know if I should use this phrase, but in a way, Jason has been like our jazz daddy–we’ve been learning so much from him. He was laughing about the jazz references we shared, which were more pop. So we came up with this concept of the “last jazz fest” related to jazz festivals and the way jazz is used in culture versus how it emerged and what it is. With a deep love of the genre, we were exploring all the ways jazz can function—and we were learning from Jason about the history of jazz and how it has functioned and can function and does function. This put all the ways we were seeing it used in pop culture into this sort of wild divorce relief. So we made this tower, which is kind of like an editing software, with the tracks sort of stems on top of each other. We wanted to isolate the band members as if they were in a music program. So the drums were on top, the piano was in the middle, and the bass was on the bottom. And then the effects channel, which is Ashland, was on the side. The layout changed a bit to fit everything.

MINES: While we were designing it, I thought it was really important that it be dangerous. We went through a few different designs that were built off of musician abuse a little bit, but the piano being elevated on this scaffolding, like a feeble-looking structure, was a big part of it, too. Moving that to the mountaintop was a different experience than doing it in a black box theater, where we intended for it to be built initially.

OZER: Lizzie, I read in the performance text that you “equate the composition of sonic loops and patterns to weaving textiles.” Can you elaborate on this?

LIZZIE FITCH: When Ryan and I first started making music together, we were using this program called Fruity Loops. I have a really non-traditional relationship to writing music. I took piano lessons when I was tiny, but other than that, I had no knowledge. However, for me, using 3D Loops became about looking at patterns and thinking about weaving. I was such a visual music writer. I was just thinking, “Here’s a note and here’s the jump, and then here’s a jump that looks the same as the jump.” And so I was just writing music that way. And Ryan’s an amazing piano player. So, my approach to writing music was to make these things that sounded crazy and felt like textiles for me and then give them to Ryan, who could make the greater form from it.

TRECARTIN: The files always looked like drawings, and every instrument, whether a guitar, sax, or anything, was treated like a drum.

MICHAEL BEHARIE: It sounds great. A lot of her “Fruity Loops” are in their Any Ever films.

FITCH: Lately, my approach to writing music has been very different because, with all the new software you can get, it’s much easier to make things fit together properly, which frustrates me. I don’t like that.

TRECARTIN Lizzie made a country album in 2014 that was never released. It’s really good.

OZER: Maybe it’s about time.

ASHLYN: Drop it.

LIZZIE: It needs some work, but—

ROSS: We put a lot of it in the welcoming music when the audience first came up to the mountain.

OZER: How was your working process? Was it this continuous process of sharing and translation, or did you meet as a group?

TRECARTIN: We had periods of coming together in New York, and then otherwise, a lot of development happening in our studios.

MINES: Ryan made so many compositions, so a big part of the initial process was for Michael, Aaron, Ryan, and me to go through everything for a really long time and try to figure out which songs we wanted to do, which ones made the most sense, which ones we could even possibly translate to an orchestra.

TRECARTIN: When Aaron and Michael translated stuff, they’d ask, “How do you want this to be played?” I would say a sentence, and then Aaron would say, “Those should be the articulations.” I don’t read music, so I didn’t really know what articulations exactly were, except for where it’s like staccato and legato and stuff like that…

ROSS: That’s usually what they are. They’re not normally the way we did it. I was getting these notes from Ryan during some 38-hour period where he didn’t sleep, and I think he was just doing them all at once, so I could almost track his state of mind as he wrote them. It would just be like a quick little idea that came to mind about how it should be performed, like the spirit of it. It’s a really fun meta layer to all the music I only got to see, as it’s the conductor’s score where all of them are.

OZER: What were some of the articulations?

TRECARTIN: At one point, I told a musician to play the section “like you are a mom with a wine glass dance walking on cobblestone.”

DANIEL MERRITT: One of my favorites is “work a body roll into a hallway conversation.”

BEHARIE: I feel like that’s one of the articulations that the band really got.

TRECARTIN: Aaron and Michael, I’d be curious to hear about what it was like translating the drums. Also, you spoke about the quantized aspect of computer sounds versus the human ability to play certain things…

ROSS: The drum stuff was a very manual process where we took the stems from Ryan’s compositions, which were drum tracks in many cases. Sometimes, it was easy just to take a midi file representing the performance and translate it to the different positions on the drum kit. But other times, we manually cut things up and figured out where things looped so that we could use the same samples in multiple places and save space on their instruments for other samples. So it’s this kind of reverse-engineering what a performable version of the part would be.

MINES: It also wasn’t just drums. It was any electronic samples that were happening in the compositions that were translated being played by drummers. So you hear stuff that sounds like it’s maybe just a backing track happening, but actually, each piece is being played by the drummers who were all playing electronic sounds…

ROSS: They’re playing little scream sounds or something. I guess the scream sound might’ve also come from Ashland. There were multiple scream distribution points in the show, but I think in one of our original meetings Ryan said, “We should get a choir of screamers for the show,” so we technically did. All of the weird electronic sounds and stuff like that needed to come from the ensemble because we decided that we didn’t want to do a backtrack, which was ambitious, and I am really glad that we did it that way because I think the recording sounds so live. It would have been much easier, but it wouldn’t have pushed us to go 100% of the way there, and I’m glad we did.

ROSS: There are certain things in Ryan’s music where two events will happen really, really close together. In the computer world, that sounds like what that is, but in the human world, that sounds like two people trying to play together but accidentally just being slightly apart–so it sounds loose instead of tight. There are moments when we want to accentuate it, stretch it out, and make it a little clunky. And then there’s stuff that we want to smooth and make tighter with ensemble playing. So we were figuring out those tolerances. Humans are never going to sound like the computer, and that’s the good thing.

OZER: Did you use a lot of samples and past projects, or is the music original?

TRECARTIN: Almost all of the songs were originally written during summer ’21 or ’22 when I was doing a lot of gardening and tree sculpting. I was writing songs to play with plants and was sharing things with Aaron. We were working on an album when this opportunity presented itself, so we wrote new songs.

OZER: To play for you while gardening or for the plants? Who was the audience?

TRECARTIN: Both.

OZER: And the title, AUDIENCE PLANT 2024?

TRECARTIN: We wanted that title to be open to interpretation. Still, I was thinking about how you don’t get to pick your audience once something is out in the world. We’re also living in an era where the response is sometimes planted, and you’re not quite sure if a reaction to something was orchestrated or if it’s an invention that came from something existing in the world. Also, in an election year, I was thinking about the way responses can be planted and how an audience for an event can be planted.

RYAN: People may not know, but there were a lot of improv sections. It was wild.

MINES: Yeah, the jams were these improvised moments in between. The compositions were something we started at The Armory, and not to sound crazy, but they might have worked best there because of the situation and how much preparation we had. We wanted to bring that through to this performance as well. We invited these super talented musicians and then we’d give them very funny pieces to play where they can’t actually show any of their actual talent. Or, it’s not as legible, because they’re reading something crazy or they’re playing some crazy sound effect or whatever.

ROSS: Like JK [Kim] not having a drum kit and playing his little sounds back and forth. When he got on a drum kit, he became this octopus.

MINES: We wanted to have moments where those artists we had with us could bring out their true powers. We also wanted to have these moments juxtaposed to the structure of Ryan’s compositions as a kind of palate cleanser.

ROSS: I’m not sure which one was the palate cleanser.

MINES: I feel like the interstitial jams kind of draw attention to the bizarreness and specialness of Ryan’s compositions and make it clearer, in my head anyway, how much work went into it and how much work the musicians are doing to make these songs happen, as opposed to freestyle loose moments.

ROSS: Matthew’s [Jamal] improv was insane. He did not do that in rehearsal. He saved something.

MINES: His solo happened just as the sun dipped, so the light changed and it opened something. It sent something somewhere.

OZER: Which instrument was Matthew?

TRECARTIN: The bass player.

BEHARIE: He turned to me before the show like, “Oh, I’m going to go in.”

MERRITT: Our knees buckled. We were like, “Oh my god.” It was so insane.

RYAN: There were people enjoying it near them. And remember, Daniel, you were like, “Let’s clear those people.”

MERRITT: Well, these people who came, they were next to the truck, and the entire performance was powered by this guy’s electric truck. I didn’t want to harsh their mellow, but it all could have been over in an instant.

OZER: That’s such a good hack.

TRECARTIN: Aesthetically, it’s great to power a concert with a pickup truck. Also, Jason improvised on top of the songs in such a beautiful way.

MINES: We had pictured that Jason might do a special feature but not want to be on stage for the whole time. We had planned for him to be in the audience and then come up halfway through and have his solo moment. But he came to a rehearsal and then the dress rehearsal we had on-site and chose to perform with us. He didn’t need the score; he just played with us the whole time. It’s crazy what he did.

ROSS: It’s really exciting hearing those additions too, because we’re so used to the songs in their sort of fixed versions that when there’s this crazy left-field layer that’s intersecting everything through the middle, it’s so exciting to have that kind of break of the repetition of the idea that we’ve heard many times. This final stage is so rewarding as a result of that.

MINES: I feel like, low-key, Jason could feel how much we had been working and trying to get everything right, and low-key, he was like, “Loosen up a little bit.” He kept goading me to make more noise or whatever. During the scored pieces, I tried to stay as far away from it as possible. And he was just like, “Come on.”

BEHARIE: Yes. Like, “Get in there.” Yeah.

TRECARTIN: He was like a live doctor. He doctored all the songs.

OZER: I love it. So he’s a doctor and a jazz daddy. Those are two really good titles.

ROSS: Dr. Jazz Daddy.