POET

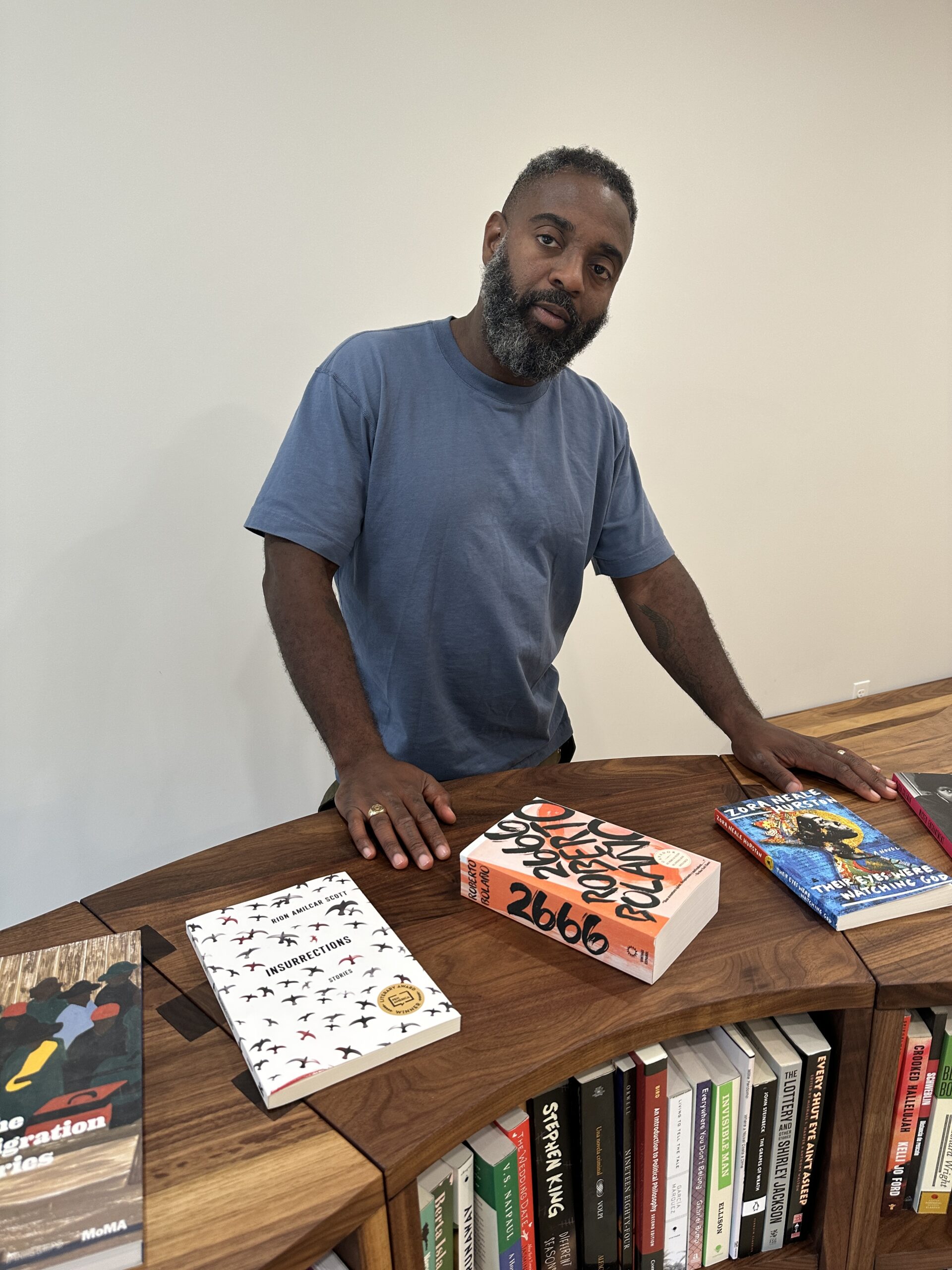

“I Always Wanted to Be a Witness”: Dwayne Betts on House of Unending

In his new album of poems, House of Unending, Reginald Dwayne Betts shares his harrowing experiences of incarceration, painting a lucid picture of the dark realities of prison life and the injustices many Black men face. The poet, truth-teller, and legal scholar has been through the system himself, so he profoundly understands the emotional toll it can take on an individual’s liberty, sense of identity, and personal autonomy. His album, scored by friend and musician Reed Turchi, reflects that. Betts also founded Freedom Reads, a nonprofit that converts prison cells into makeshift libraries to exchange books. “I think part of the loneliness that comes with being incarcerated and motivates us to do the work of building libraries in prison is that we’re sort of singing into the darkness,” said the author of Felon and A Question of Freedom, who won an NAACP Award in 2010 for his debut. “Becoming a poet was a way for me to sing into the darkness.”

Our Zoom earlier this month was interrupted by a phone call. Immediately, Betts hung up and answered, letting me know he had to put me on hold. When he got back on, he told me who the call was from: an inmate who Betts is advocating for as he awaits a decision from the Virginia Parole Board, a searing reminder of the daily strain of the criminal justice system and the quiet tenacity of people like Betts, working to fix it. After the brief interruption, Betts went on to tell me about fatherhood, voyeurism, and how prison shaped his world view.

———

REGINALD DWAYNE BETTS: Can you hear me?

MALIK PEAY: Yeah, I can hear you. I’m so excited to be speaking with you today, Dwayne. How have you been?

BETTS: I’ve been looking forward to this.

PEAY: I’m going to jump right in because I really want to talk about House of Unending. How did you first approach this project compared to other kinds of performance, like poetry and spoken word? This feels new and fresh.

BETTS: In some ways, we thought of it like old school improvisation. You got somebody with a guitar, you got somebody with some words, and we come together to make something happen. Between what Reed [Turchi] does with the guitar and what I was doing with words, we can let the poetry live in a different space.

PEAY: How long did it take to make?

BETTS: Really, you’re talking about spending two days in the studio. And everything we recorded, we kept.

PEAY: Oh, wow.

BETTS: We got some other stuff that we aren’t going to release on this album. But it really does feel like a live album in that what we get in that session is it. It’s my first time doing this, but it really set me up for a different kind of experience.

PEAY: It does feel very experimental.

BETTS: I’ve known Reed for a while. His father was the director at the school where I got my MFA, and we carried the vibe from that school into this project. I remember one of the earliest times me and him were kicking it, we were playing basketball years ago. I was like 27, he was still a teenager, and we were playing two older guys. And it’s strange how the basketball court captures so much of what this collaboration means, because it really is like a game of two-on-two. You’re playing off the other person, but you don’t necessarily know them as well as if you were on a team with them. So this became us playing off of each other and producing something that we felt was magical and worthy of a studio session in the old sense of the word. We put it out on the album and then let it linger in the world.

PEAY: You painted this visual and really in-depth texture of what it was like to be convicted and to be in prison, but also, of the systems that impact marginalized people and keep them in prison. I found it really powerful. I really liked one of the songs about the underground libraries that exist in prisons. I feel like some people don’t expect the degree to which knowledge is shared between cellmates.

BETTS: Yeah. When I think about how these songs exist in the world, it’s a man singing out to a community. I think part of the loneliness that comes with being incarcerated and motivates us to do the work of building libraries in prison is that we’re sort of singing into the darkness. And becoming a poet was a way for me to sing into the darkness. This album is a different kind of singing, and the guitar becomes a kind of special sauce that you get with this particular project.

PEAY: Yeah, I agree. I feel like the listener is kind of peeking into the life of an incarcerated. “Essay On Reentry” feels very intimate, there are these personal collected calls that you give. How did it feel orienting that with Reed and layering his guitar on top of the tracks?

BETTS: I think that he’s always been the musical arranger of the group. His skill gives me the freedom to just show up and hear the effects. Often, I can’t even hear what’s going on because I’m doing my thing. So it’s only later when I hear it and I’m like, “Oh, man, that actually sounds good.”

PEAY: Yeah, your voice really sounded powerful on top of the riffs. I feel like you’ve shared this wide-eyed experience of existing as a Black man in America. On “Going Back,” you talked about reminders of mortality—of half-a-dozen Black boys sitting on crates, passing words, of HIV victims, or men being robbed.

BETTS: It’s confronting a bit of tenderness that exists in those moments as well. Some of my earliest recognitions of the tenderness that men in really violent circumstances show for each other are from scenes like that. So I’m trying to capture that complexity of emotions.

PEAY: It really showed how we alleviate our own stresses and find camaraderie between people. On “Losing Her,” though, you talk about both blooming romance and thoughts of suicide. You have this metaphor of God throwing dice at your school. Were you exploring the idea of difficulty finding love after being impacted by the prison system?

BETTS: Yeah. I was thinking about how to talk about things that are troubling. One of the things that’s really troubling that prison sometimes produces in us is domestic violence. Sometimes we have it before we go to prison, a kind of violence that leads us to hurt the people that we love. I want to be the kind of artist that creates some space for us to have really difficult conversations. Because it’s those difficult conversations that go a long way towards changing something about how we do things in this country and our communities.

PEAY: Yeah, and in “Blood History,” too, which I felt was one of the most compelling tracks, you talk about Black men and their relationships with their fathers. What does your own blood history and lineage mean to you?

BETTS: That’s a really good question. I think about what it means to be my father’s son and how it has to mean something about who I am to my own children. It’s something that I grapple with a lot, because being a father is one of those things that’s really important to me.

PEAY: It is the legacy that really does follow suit. Even with my own father, it’s a very intense relationship, but I do really appreciate his perspective and am inspired by him. Going back to the vivid imagery you paint of living in prison, like on “Missouri,” when you talk about overcrowding and lack of human essentials, is talking about these experiences healing work for you?

BETTS: That’s an interesting question, because what do we mean by “healing”? I try to contribute work that heals my community. I always wanted to be a witness, because a witness survives. That’s what it means for me to be a storyteller, to be a witness to what needs to be said about and to my community. And being that is nourishing, because I feel like I’m serving my purpose. But doing this work doesn’t address any of the real pain that comes from the experiences that I’ve had in prison. Whether or not that will heal is a different conversation and sadly is one that my writing plays very little role in.

PEAY: Have you ever had instances with other prison mates where you made them feel seen or healed?

BETTS: Yeah. But I think one of the real challenges in this work is that once people think of you as an in-group, they say stuff to you that they wouldn’t otherwise say. And that’s frustrating because it teaches you something about the world that you didn’t know. But the other challenge is admitting what you can’t do. And that’s a little humbling. That ain’t easy.

PEAY: It definitely takes a very strong mind. You also mention addiction in former prisoners in some of the songs, can you speak to that?

BETTS: Sadly, some people develop habits inside. I mean, people live whole life cycles in prison. Sometimes we forget that. We think that their soul is just held and suspended in animation, but it’s still living. I know people who have helped create methadone clinics and help bring AA and NA to prisons. But to tell you the truth, I’m fortunate. I was a young kid, so I didn’t have any addictions when I went inside. But I’ve seen other people deal with it, and it’s a struggle, because narcotics and alcohol can just frustrate everything else you are already struggling with.

PEAY: Yeah, you paint these visceral life cycles that these men go through in prison while lacking autonomy. You mentioned this in “A Man Drops a Coat on the Sidewalk.”

BETTS: Man, you listened to all of these songs.

PEAY: Yeah, I went in. But that song really took a while for me to decipher.

BETTS: Look, some of these poems actually happened. I think music is the same way. But some of these joints, straight up, they happened. And some of it is really crafted, and it’s a story, pulling things from different places. As a poet, you’re trying to contain multitudes. If I really want to give you what I see of the world, I can’t just put my life on an album. You know what I mean? I carry around the lives and the stories of a lot of men with me. And I’m trying to put all of that onto a record.

PEAY: Right.

BETTS: Sometimes though, the muse gives it to you clean. At the time, I lived at an apartment complex right in front of the old Winchester gun factory. And it was a fascinating scene, because it represented for me the destruction of guns, but also the line that divided one part of New Haven from another part. It also represented this part of New Haven that had disappeared. The factory work was good employment for Black folks, and it had disappeared, and in some ways, what was left was just the violence that the idea of a gun armory represents. So I’m driving by there, and I see these two dudes, and they’re obviously high. And I’m entranced watching them, because they’re two lovers moving in slow motion. The whole scene became transfixed with them, including somebody else that was driving past and reached out their arm to take a picture. It fucked with me that we’re often entranced by ruin, but not enough to imagine doing something for the people that we are watching. So the poem is both a confession and me trying to capture that moment. The confession is that I’ve been there, looking lovingly at the disaster that I’m not willing to pause to help fix. And it’s also about the disaster that’s there that we should be thinking about. It’s weird trying to both play the role of witness, but also confess the ways in which sometimes witnessing ain’t enough.

PEAY: So many people are enamored by the idea of a spectacle, even if that dehumanizes the people they’re observing. I do want to speak more largely about what creating House of Unending feels like for you and how you think others will attach themselves to it.

BETTS: I think you do something and you sit on it. I mean, while we’ve been having this phone call, I got a call from somebody that’s locked up. I think the House of Unending is chronicling stories you want people on the inside to have and also recounting some of what matters to folks who haven’t seen it all. Being a witness is telling stories for them too, not just stories about them.

PEAY: And making sure they feel seen. I’m so thankful to have been able to speak with you today. I wanted to have a very in-depth conversation with you about this work, because it deserves that.

BETTS: Oh, man, it’s my pleasure. It was cool.

PEAY: Take care.

BETTS: Thank you.