Stories Tom Krell Tells

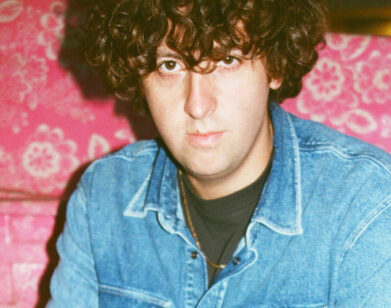

ABOVE: TOM KRELL, AKA HOW TO DRESS WELL

The title of the gorgeous new How to Dress Well album is a question: “What Is This Heart?”, complete with quotation marks. When we met Tom Krell, the Chicago-based solo electronic R&B musician behind the project, for coffee last month, he explained that the quoted aspect of the title is especially important. “It’s not a written question, it’s a spoken question,” he said. “It’s either spoken to no one or to someone, anticipating some kind of answer.”

We asked whether, in his view, the question was addressed to someone. He paused, as he does every so often—Krell speaks carefully, and usually in paragraphs—and said yes. “To the whole world,” he said. “But then, there’s also the willingness to attribute the question and not settle for an answer.”

After 2012’s Total Loss—a devastated, and devastating, album inspired by the death of Krell’s best friend—What Is This Heart?, his third, inspires all manner of contradictory description: it’s both lighter and deeper than the previous two. Krell lays bare his musical influences—handily, you can listen to them all at this Soundcloud, in fact—but finds as much or more inspiration from fiction and film, and from any endeavor that attempts to address the question of how to try to be a moral person in a world that isn’t.

ALEXANDRIA SYMONDS: I love the quote that you sample near the end of What Is This Heart?, from Stories We Tell, about how discovering some new truth can beget more of that kind of discovery. That film!

TOM KRELL: Yeah, it’s really profound.

SYMONDS: I think I left my brain in the back of that movie theater. But to talk about themes, it does seem like this album is very open about family.

KRELL: I put that quote in there after “Very Best Friend,” the “poppiest” song. Every time I think that I’ve pierced through the simulation, every time I feel like I’ve written something authentic, it feels like I then sort of lose my footing with it. “Very Best Friend” was an attempt to make a beautiful pop song, a bubblegum love song, but then it breaks down into this choral sevenths arangement that becomes a little bit menacing.

SYMONDS: Which happens a lot on the album, these eerie shifts.

KRELL: Yeah, that’s sort of the vibe. I can’t really stomach the simulation for too long. But I just love the way that the movie engaged with the possibility of telling the truth, and made it more complicated than: on the one hand, falsity and simulation; on the other hand, truth. The simulations end up being the bearers of a lot of the truth in the movie. I can say like a really grave lyric, and you think, “That’s going to be the one that really hits me,” but what actually hits you is the pop love of “Precious Love” or something like that. The whole record to me was an opportunity to experiment with the relationship between simulation and pop, on the one hand, and confession and being known and really questioning on the other hand. I love that film so much.

SYMONDS: When people talk about breaking down binaries, like, “Truth versus fiction is not a binary,” the easiest next step to go to is, “Oh, it’s a continuum.” But I think that’s often not true either—rather, there are many splintered versions of either of those binary categories. I think that’s something both Stories We Tell and your album deal with.

KRELL: It’s not a continuum—and fiction can produce truth, and truth can be false. What does it mean to say that it’s true that, what, two out of six people in this city are starving? That’s true, but that is only true because the conditions we live under are completely wrong—that should not be true, and it is. And in something like Sarah Polley’s film, her fictions deliver so much truth. The retellings and the simulations and the theatrical aspects are what deliver all the truth. It’s not like you break down the binary and there’s mixed versions; there are actually crazy hybrid versions, truth where you wouldn’t expect it, fiction where you wouldn’t expect it.

SYMONDS: On What Is This Heart?, you can boil down any of the songs to, honestly, pretty simple thematic kernels. But then what’s interesting is when, musically and lyrically, they do that act of splintering.

KRELL: The interesting thing about doing press is that I learn what the album is about—I now know, a year later, looking back, what was on my mind at the time. It’s cool, because on the one hand the songs are all indexes of a time in the past when I was writing them, but I also don’t remember when I wrote different parts. I’ll try to place a song, “Where was I working on it?” And I’ll remember, “Oh, we had a day off in Warsaw and I tried to sing these melodies,” but I can’t place when I got the drums together. So there’s this weird thing: after making this record, I look back and try to piece my past back together.

SYMONDS: The impulse is to look at it as something that sprang fully formed?

KRELL: Well, it feels like that. And I kind of return to things and see what I meant to mean, what I was feeling or dealing with. The same thing happened with Total Loss—I realized, after writing the record, that I was going through a process on it. This last year, we did like 200 shows; we spent so much time on the road, all over the world, and I just started to feel incredibly disoriented and decentered. The weird thing about Total Loss is that something really, really concrete and brutal happened—my best friend passed away—and then I ended up writing this record which, to me, ended up being pretty gauzy and weird and indirect–an indirect way of mourning that really concrete thing. This record comes out of more weird, indirect, decentered feelings—feeling placeless and groundless—and I ended up making something that, to me, feels really on the ground, super confident and really strong. Which is weird, because it didn’t come out of that space at all.

SYMONDS: Maybe there’s a way you have to act against what you’re feeling. Do you think there are people who are naturally nomadic? Sometimes you meet people who say their most natural state is with a few possessions in a bag, and a passport.

KRELL: I guess there are those people. They’re usually under the age of 20.

SYMONDS: Yeah, I don’t know to what extent that’s…

KRELL: Viable?

SYMONDS: A real way to live, yeah. How do you handle that aspect of the life that you’ve chosen for yourself?

KRELL: Not well. It’s totally different, also, being on the road, because you do so much waiting and so much traveling. It’s not the same thing as being in the same city for a week or two weeks and then another city. It’s really hard. I don’t think people understand this about being a touring musician, or a touring actor, or somebody who flies everywhere for business. It’s incredibly disorienting. Luckily, people come out to every show and make it 100 percent worth it. I reveal a lot at shows.

SYMONDS: Are there any sort of experiential talismans that you can grab onto? Can you read something you’ve read a hundred times before and feel at home no matter where you are, or is it not quite that easy?

KRELL: I don’t have one thing I go back to, but we listen to a lot of music in the bus, and we always get a few songs or a few records that end up being themes for the tour. I spent last year—and a major influence on the record is—I read all of George Saunders’ short stories and all of Alice Munro’s short stories. George Saunders is who has taught me about this question about whether or not love is possible in the contemporary world, with all of its simulations and all of its pop and divergences and all of the confusion and distraction. Whether or not contemporary reality is actually hospitable to love.

SYMONDS: He is a very comforting writer. A lot of the time when you read very dark, dystopian work, either a) that impulse is completely absent or b) it’s written in as a totally unbelievable afterthought. For him, it’s what almost grounds his stories: the ways in which that essential love, or connection between people, is getting fucked up, but is what we need to be getting back to.

KRELL: I think that a lot of dystopian literature tends to be really moralizing and just doesn’t tend to give credence to the importance of the sentimental. Maybe it says, “We need love in this world,” but it’s always this tough, strong [statement]. George Saunders is such a wimpy guy.

SYMONDS: [laughs] He’s such a softie! He’s in Chicago, too, right?

KRELL: He’s outside of Chicago too, yeah. I’ve met him a few times, actually. I really like him a lot. He’s a really sweet guy. He’s a big fan of my music now, too. I spent an enormous amount of time reading his work and Munro’s work, and also watching the Dardenne brothers’ films. Do you know these films?

SYMONDS: Yeah.

KRELL: The song “Pour Cyril” is for the little boy from The Kid with a Bike.

SYMONDS: Oh, I didn’t even make that connection.

KRELL: I love their work—it does something like Saunders, it shows that lining of love, still, in this totally-fucked world, but it’s never like a happy lining, it’s always desperation. It never ends with anything like a resolution. It always cuts off suddenly, like, “Oh no, this is the fate of the world.” There is some interesting story to tell about Saunders’ optimism versus their grittier realism.

SYMONDS: A word that gets bandied around a lot in association with their work is “humanity.” Which is true, but also such a strange way to categorize things—if you’re depicting a realistic and subtle story, as opposed to any other kind of narrative, that’s what it is to be a director full of humanity.

KRELL: It’s a really small kind of humanity. It’s not like the titanic “humanity” of humanism, it’s much more gritty and realistic. But again, humanity is what unites all the people I’m talking about, and in such different ways. The humanity is in that moment you glimpse someone and have a completely intimate moment with them, and that intimacy is connected to an extreme pathetic aspect. In The Boy, when he says, “Will you be my guardian?,” it’s the most beautiful moment of love imaginable; and then he falls asleep and jerks the wheel and his wife asks, “What are you doing?” He’s like, “I don’t know.” That’s like the moment of humanity that I love in Munro and the Dardenne brothers, that moment when you bear yourself out with a question mark.

Not confessional in the sense of Dashboard Confessional, singer-songwriter, “This is me, face it,” but: What is the status of a confession which confesses that it doesn’t know? That’s the meaning of the question for me. This is a very confessional record, but it’s not like I’m confessing either secrets or any positive content. What I’m confessing is that I’ve grown to a point where I feel like I should have more answers, and I don’t. And I still think that applies in the Saunders stuff. You know that story “My Flamboyant Grandson”? It’s so beautiful, right?

SYMONDS: [laughs] Oh my god, yes.

KRELL: [laughs] Remember the grandfather, he doesn’t know why he’s doing what he does, he just knows he doesn’t want to make his grandson feel the way his grandfather made him feel about his fat calves. So all he’s doing is moving away from something he knows was bad. He’s not moving toward something good, which has the character of capital-T truth; he’s just desperately trying to do something good in the face of a world that’s totally inhospitable to goodness and love. And in order to do it he ends up bleeding and broken. It’s beautiful.

SYMONDS: That acknowledgement of cruelties that are really tiny is also a thread among all the things we’re talking about. Alice Munro does tiny cruelty better than almost anyone. Maybe Lorrie Moore.

KRELL: I think what’s interesting about Alice Munro, too, is the extreme mundanity of things. And how even a life reduced to complete mundanity, like capitalism taking over rural Ontario or whatever, has complete sway over aspects of life. Nevertheless, people still have these moments of weird desperation, weird longing, weird true love, or weird, powerful lust, and that was a major inspiration for me, too.

SYMONDS: So if you’re writing through those kinds of things that you’re thinking about…

KRELL: Well, I was more living in the zone of all that stuff for about a year. Playing live is so weird because I go out there and I try so hard to give something, which will be recognized. And in turn, something will be given to me, there’ll be some kind of shared moment in that. So it’s very affectively intense–so much longing and lack of control. One of the things I’ve really loved about playing with Aaron, my bandmate, is that we’ve added more and more elements, which we can’t guarantee. A lot of electronic-based musicians give very low-risk performances, and it’s fun to hear your favorite band play live on a big speaker, but the live context is about the moment of risk and that moment of possible failure. And that’s another thing in Alice Munro: it’s always, like, some middle-aged woman who is going to cheat on her husband, and there’s that moment where she decides to take an extreme risk. It’s always after an extreme risk where life really happens for Alice Munro. So that story I’m thinking of was in Friendship of My Youth, but then there’s a new one in Dear Life where this young woman goes from a school she’s teaching at to meet a man, and then she gets there and it’s like kind of a weird letdown, but then also becomes a normal life again. But life happens after that moment of risk.

SYMONDS: It’s such a good title, too.

KRELL: Dear Life? It’s what I would have called the album if it weren’t taken, for sure.

SYMONDS: Just in quote marks would be fine.

KRELL: [laughs] Exactly, it’s such a beautiful title, and it’s so her, too. It’s so courageous. This is why I love her. Every time I see her face I just feel inspired, because she’s willing to love life even in those moments where it’s most pathetic, most desperate, and the most grown people doing completely juvenile things to one another and to themselves. And it’s still dear to her; she still writes with this love and care, with incredible tenderness.

I didn’t sit down and write a song like, “I want to write a song about this,” but I just spent so much time living in this affectively charged space of the live show, with its risks and the incredible reward that comes from people knowing me, recognizing me, affirming me. And then I would wake up in the morning and have an eight-hour drive where I would read Saunders and listen to Grouper and Pure X. And you bond so much with your tour-mates and your bandmates because it’s this weird, quite desperate way of living, kind of place to place, clawing around, looking for some good coffee or food or someone to talk to, something to ground life.

SYMONDS: Is What Is This Heart? an album you wrote about how you think the world is, or about how you think you are?

KRELL: I believe, and this is something I also learned from Alice Munro, that there’s a moment where the personal becomes totally universal. When you see that person in their pathetic moment, that’s the moment where the completely unifying sympathy with that person is possible—where you’re no longer a person here and they’re someone over there, and you can really feel like one, you can really feel like a human being. Or more like, you can really feel like flesh and blood, because I feel like that moment is the same thing with animals, too—when you see an animal starving, or when you see an animal in pain or in a joyous release. I have no trouble, at that moment, being completely the same as that cow. Have you seen this video of these cows who have been in a dairy farm, a really shitty one, their entire lives, and they’re let out into a field, and they’re literally jumping with joy? It’s crazy. I don’t have any trouble completely becoming that cow. There’s no “What is it really like to be a cow?” kind of question anymore. There’s no question at that moment whether I understand you completely. I think there is, in that moment, a possible total sympathy. Total sharing.

SYMONDS: It’s funny how physical a response sympathy is. It’s talked about as something emotional, but when you feel something like vicarious joy, or especially vicarious embarrassment, like when you see someone do something embarrassing and you feel it for them—

KRELL: Oh, yeah. I suffer this enormously all the time.

SYMONDS: What happens to you is not like a mental, like, “Oh, that poor person.” It’s heart palpitations and blood rushing to your cheeks for them.

KRELL: Well, I feel like real thoughts and emotions involve the whole being. And they also outstrip little personal quirks, and they outstrip biography. You end up on a really special, universal, shared terrain in those experiences. I think it’s available to absolutely every single thing made of flesh and blood. Interviewers like to ask me, “You sing these sad songs; do you have to, like, make yourself sad before you go onstage?”

SYMONDS: [laughs] How would you go about doing that?

KRELL: Yeah, script says, “Cry.”

SYMONDS: Just watch The English Patient every night before you go on stage.

KRELL: Every night. No, luckily, like for instance the song “Suicide Dream 1,” I wrote it out of such an incredibly powerful state that the melody carries that affect. So when I produce that affect, that melody, with my body, I’m immediately thrown into it.

On the one hand, this is my most personal record, but then I hope it also makes that turn—where it’s not, like, “Inside Tom Krell” or whatever. It’s inside the space of that question, What Is This Heart?, which to me is also the universal thing. That’s the question that—asking that question or refusing to ask that question or being unwilling to ask it or asking it and not really being aware that you’re asking it—that’s what leads all of Saunders’ and Munro’s and the Dardenne brothers’ characters to do what they do. We listened to a lot of Everything But the Girl on the road, Tracy Chapman. These artists are throwing themselves into the space of that question and trying to find something like an answer there. We listened to a lot of Prince, too, which I think is probably evident in the record. And a lot of Craig David.

SYMONDS: How do you tend to feel in the five to 20 minutes after a show?

KRELL: Completely ravaged. I have this problem where I get incredibly, miserably nervous every single show. This is part of why touring is so exhausting for me. I have not gotten to a place where it’s like, “All right, here’s another.” It just doesn’t feel workaday, at all, yet. Maybe it will eventually. That would be great, because it’s kind of killing me, being so nervous so many hours of the day. After the show—we try to end on an anthemic note, and I try and let that be decisive, and I will often come back out for an encore a cappella, and that’s where I try and take leave from the feelings of the stage. Trying, after I do that, to return to my life.

SYMONDS: So that’s the transitional space?

KRELL: Yeah, exactly, the threshold. But sometimes I’ll go out to say hi to people, and I’m just not ready for it. It feels too weird, too intense.

SYMONDS: This is something that probably ties in with a bunch of things that we have been talking about—I wanted to ask about the line on “Face Again”: ” I don’t really know what’s best for me,” which, in repetition, takes on this desperate quality, at least to a listener.

KRELL: That’s the vibe, for sure. “Face Again” is actually the most Saunders-y song. Basically the verses, I’m describing a world where love is being killed, and then in the first chorus, I’m sort of protesting it. It’s like, “I don’t think you know what’s best for me.” And then by the end, it’s like I’ve given in, and it becomes very desperate.

SYMONDS: How does that song fit into the album, for you? It would be my go-to if someone wanted to know what the album was about but could only listen to one song.

KRELL: That’s very much a centerpiece song, that and “House Inside.” They’re so worlds apart, but they’re both about struggling to find some kind of genuine experience. “Face Again” is about genuine love and living right as an individual. And then “House Inside” is about family and the future and the past and how to put them together in a way that honors the past but then doesn’t get bogged down and caught up in it. Our present era, to my mind, is characterized by a profound forgetting of the past. “The future, the future, the future.” The 21st century, all the technology obsession.

SYMONDS: Do you feel like that’s true in America or everywhere? It seems weird to me that you, as someone who lives in Berlin some of the time, think of our present era as one that’s obsessed with forgetting the past. Berlin is very concerned with…

KRELL: It’s actually maybe even more relevant in the German context. I have a German friend who works on memorialization. The last generation of Nazis and Holocaust survivors are now dying. So literally, we are threatened now for the first time ever, with memorializing that, with no first-person account of it left on earth. There’s a lot of worry amongst scholars in Germany about what comes next: “All the memorialization has been done, we’ve done with everything we can.” I was reading this book by this guy Jean Améry about the Holocaust about eight months ago. It was fucking so miserable and so amazing. He hates the idea that people feel like they have done enough to memorialize. They’ve made it part of their culture and he thinks they haven’t. He’s obsessed with resentment, holding on to the past. Yeah, I do think that we’re pretty future-obsessed right now, and I think that capitalism works best when we have a very short memory of the past, when we can just go forward seamlessly into a future of ever-new products and ever-new experiences—even though they’re exactly the same, just on a watch instead of on a phone or whatever.

SYMONDS: I saw a tweet a couple days ago that was like, “Look at this cool new smartwatch design!” And someone had just written on his wrist the words, “You already have a phone.”

KRELL: Yeah! Every new generation of smartphone just has a different-shaped button. It’s embarrassing. “Face Again” is a lot about, if there is no past, this sort of fear of the future. “House Inside” is way more literally about having a different relationship with the future than the one described in “Face Again.”

It was a weird thing to freestyle, by the way—that future going into the past thing. Also, like, “Childhood Faith in Love,” I freestyled that chorus word-for-word in one go. And then I listened back and I was like, “What the fuck?” I free-associate vocally, and I listen back and sometimes there’s bits and pieces; sometimes a whole phrase comes out. In that case, it was the whole chorus. “Everything must change, everything must stay the same.” Those are good words to have circling around in my head. I just wish that I was able to deal with them, not by singing, but by helping myself. But singing helps, too.

WHAT IS THIS HEART? IS OUT NOW. FOR MORE ON HOW TO DRESS WELL, PLEASE VISIT KRELL’S WEBSITE.