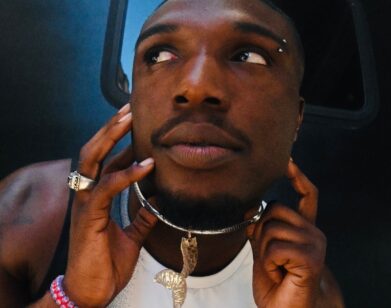

Get to know the breezy pop of British artist to watch Westerman

Sometimes artists appear to exist in a bubble of their own making, concerning themselves with just their own thoughts and their work, leaving the world at large to make of it what they will. Many successful writers, as their career matures, develop a working method like this, which deliberately isolates them from distractions and helps them stay productive. But it is rare to find a young musician who already seems to have constructed those barriers and writes from that studious self-exile.

Will Westerman, who performs under his second name, is 26 years old, lives in London, and is only a short journey from the rest of the capital’s thriving scenes. But his music and his character are so thoroughly removed from the world around him that he comes across as a songwriter slightly out of sync with the city. He talks about recent work with producer Bullion as if the very idea of a communal studio process struck him as a novel and radical experiment, “It opened up a completely different way of making music, to be working with a sound other than your own.”

If it was an experiment, it was a very successful one. Westerman produced some sparse folk songs a few years back that built upon his intricate guitar playing and quiet vocal lines. It offered a brief glimpse of an artist thinking hard about song-writing in a very simple and precise form. It’s that same thoughtful minimalism which has been harnessed to produce a new set of glowing pop songs that have, for the first time in Westerman’s life, attracted him a great deal of attention. Recent single “Confirmation” clicks along on a neat synth pulse and, although its chords warp in pleasingly surreal directions, nothing overpowers the near perfect hook at the centre of it all.

Westerman’s lyrics dwell on his worries and his loves but are too tenebrous to feel biographical. Asked about his writing process he only says, “I spend a lot of time analyzing what’s going on, sometimes to my detriment. Trying to make sense of things that often I can’t make sense of.” He repeatedly returns to the idea of a fragile connection that can only exist between him and a listener if they happen to feel something when they hear his music. He is loath to even consider actively seeking these connections out, saying, “There are just pieces of music that connect with you. As an artist you just try to find some thread which conveys something and follow it and hope people understand it. Music is such a special expression of something. I don’t know if I even believe in a soul but whatever that would be, it’s an expression of that.”

Westerman worked as a teacher after graduating from university but found that the pressure on the pupils to succeed produced severe anxiety in him. “I found myself far too invested in teaching,” he recalls. “I was just really hoping that each of the students did well. It was hard for me not to become too emotionally invested because it really feels like, at the end of the day, it all comes down to you.”

He notes that school was difficult for him as a teenager and that he used his music as an escape. It is no coincidence then, that he returned to that outlet as a young adult. Again, he dwells briefly on the idea that his music might form a subtle connection between him and his listeners. “It is an isolating experience, school. If anyone has ever felt othered in any way, that is something we would have in common. There’s that thread to the listener but I try not to think about it too much.”

Westerman seems to spend a lot of time trying not to think about things too much. In his music he sings about the art of not overanalyzing yourself: “Confirmation’s easy, when you don’t think too much about it,” he sings in “Confirmation.” But he is at his brightest in conversation when he begins to discuss the art of writing good pop music, and he has a lot to say about it. He explains that, for him, the defining trait of pop is its love of a repeated phrase and that he tries to let that guide him. “The motif is what you hang your hat on each time you try to create something good. You can be clever, of course, with how you dress it up, how you invert it. But if that central idea isn’t strong enough it will never be good enough.”

As refreshingly focused as Westerman’s approach is, that search for a genuinely brilliant chorus or hook isn’t always easy. On his bright and wistful new single, “Edison,” he sings that “these lightbulb moments rarely come.” He explains, “Very occasionally, something comes out reasonably well formed. But more often it’s like fishing. It’s there on the line, but you have to really work to bring it out. It’s there, but its muffled, and imperfect. You have to help it communicate clearly, perfect it.” Once again, Westerman talks about a fine connecting line, the thread which runs out from him and through his music to another person or another idea. It’s hard not to see that concern, for the imperfect idea which needs help developing into something brilliant, as a teacher’s concern; that same feeling of responsibility which he felt towards his students. But more often than not these days, Westerman is developing imperfect ideas into something brilliant, and there are increasing numbers of people listening at the other end of the line.