The Next Generationals

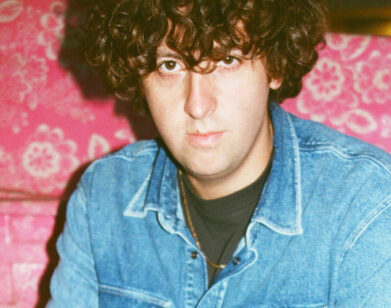

ABOVE: GENERATIONALS. PHOTO BY CARA ROBBINS

When high school friends Ted Joyner and Grant Widmer formed Generationals in 2008, it was on the heels of another, larger band’s breakup. “We knew we weren’t done making music together,” recalled Joyner when we met the pair at a Los Angeles café earlier this month. In conversation, it’s easy to gauge the New Orleans duo’s shared history—they banter like siblings and can finish each other’s sentences without missing a beat. But when it comes time to discuss their new record, Alix (Polyvinyl), both stress that getting out of the comfort zone was key.

Prior to recording, Generationals abandoned their old producer and struck out in search of something new. They found themselves at the doorstep of Richard Swift (The Shins, Damien Jurado), whose sonic fingerprint and storied persona loomed large in their collective conscious, and whose production tactics promised to shake loose whatever cobwebs had amassed over the years. Yet rather than reconstruct Generationals’ little world, Swift treaded lightly, nudging Joyner and Widmer along as they went.

What resulted is an album that builds on the band’s longstanding love affair with buoyant music and dark subject matter. On first listen, Alix‘s sunny, hook-laden pop looms large, but repeat visits underscore a sly mix of analog details and discreetly brooding lyrics delivered in bright falsetto harmonies. It’s inescapably catchy, and it just may be Generationals’ most nuanced record yet.

ALY COMINGORE: So, who’s Alix?

GRANT WIDMER: It’s actually a street in a neighborhood in New Orleans called Algiers where a lot of our friends live. I think the guy that set it up named it after his daughter or something, but we liked how it looked. We’re kind of more visual about the album titles. We like things that appeal more phonetically, rather than going for a direct reference point or some specific definition.

TED JOYNER: It’s a vibe.

COMINGORE: What led you guys to Richard Swift?

JOYNER: We met him years ago, but really briefly. He did a remix of one of our songs, but as time went on we became a little bit more familiar with some of the stuff that he worked on.

WIDMER: He came to a show in Portland that we played and we met him and he seemed very enigmatic, like a comic book character or some semi-fictional guy. One of the things that everyone kept telling us was that, yeah, he’s great at his job, but when he gets on a jag, he’s so funny it almost overwhelms everything else. He’s kind of a force of nature. We were looking for a new producer and a new direction for this record and he was our first choice, so when he was into it, it was like duh, yes, easy.

COMINGORE: Do you feel like the experience lived up to your expectations?

JOYNER: I don’t know if we knew what to expect. I’ll probably look back on it as kind of a shift in how I think about making stuff. He’s nonstop creative, so just being around someone like that is inspiring.

WIDMER: I think we were bracing for a gruff guy. You know how some genius-type godhead people are like, “You’re not here because I’m nice; you’re here because I’m good.” We were kind of expecting this bold personality that would suck our songs up into his gravitational pull and chew them up and spit them out.

JOYNER: But that didn’t happen.

WIDMER: Immediately he made us feel at home and he dispelled any fear or anxiety we had about working with him. Then we got sent on this whole other rodeo ride of crazy things happening in his little world in Cottage Grove. It defied our expectations, but for different reasons than we thought.

COMINGORE: Did you want someone to come in and completely transform things?

WIDMER: I think we were definitely interested in his fingerprint and his spin. That’s why you hire a guy like that, which is kind of the irony of the whole project. We got a call from him when we landed in Portland and he says, “I’m pretty sure this is good to go. We’re not gonna change a lot of it. I like the direction you’re headed. I like the sounds you picked out. I think I like where this is already.” I remember telling Ted and being like, “Oh shit, what does that mean?”

JOYNER: I think we were open to it. If he wanted to destroy those songs and build them back up, we were open to wherever he was going to take us. We were down for the adventure of it, because we had been so comfortable with our previous producer.

COMINGORE: Whose idea were the horns on the final track?

WIDMER: That was Ted.

JOYNER: Yeah. I mean, they’re synths, but…

WIDMER: We hadn’t done that in a while, actually. Our first record had a bunch of horns on it.

JOYNER: Real ones.

WIDMER: But it kind of bit us in the ass because we didn’t tour with horns.

JOYNER: That’s always weird, re-rendering that for the live setting if you can’t get horn dudes, which you usually can’t.

COMINGORE: I was talking to someone recently who told me that when you hire string players you usually get aces, but when you hire horn players you tend to get drunks.

WIDMER: Yeah. There’s all kinds of wisdom out there about how to do that. We used to go through the promoter of the show and say, “Hey, we’d like a few trumpet players. Do you know anyone in your area that can play?” Usually three or four guys would show up and they’d have various levels of aptitude. The thing is, our parts were so easy that we were confident that if you volunteered—

JOYNER: Or if you were very drunk—

WIDMER: You were probably good enough. But you do get people who want to, like, put their own spin on it.

JOYNER: There was that dentist guy we were using for a while. He was in his 60s.

WIDMER: He’s in New Orleans, right?

JOYNER: Yeah. I’m still friends with him on Facebook. He actually hit me up recently… Johnny!

WIDMER: I can’t even remember how we found him in the first place.

JOYNER: I think you found him online, but the way he was communicating, he’d say things like, “Now don’t go around my back and find anotha’ horn player on me. Don’t double-cross me, ya’ hear?” We couldn’t figure out what his deal was. He sounded like an old-timer. But then he showed up and he was great. When we did shows in New Orleans with him girls would always come up and be like, “I love that guy!”

WIDMER: He was so into it! It was really infectious.

COMIGORE: I do want to talk a little bit about New Orleans, just because I feel like so many people romanticize that city.

JOYNER: It can be romanticized to death. It has a weird sort of intoxicating mystery to it because of the architecture, the physical environment.

WIDMER: I feel like in almost any city there’s a block or a vantage where you can walk and when the light hits just right and you go, “Whoa, this is really something special.” You can find it lots of places, but I feel like New Orleans has an extra amount of it. There are a lot of places where if you had been unconscious and you came to right there you’d think you were in a different era.

COMINGORE: Have either of you had any ghost encounters?

JOYNER: I really wish I did, because there are so many hauntings.

WIDMER: The ghost economy is a real thing there. There are lots of people whose full-time job is explaining ghosts—ghost tours, horse drawn carriage ghost tours…

JOYNER: Ghost tours stop at my building. One time I walked past the window and caught the eye of someone on the street and they were like, “Oooh, look look look! There’s a man up there!” I was the ghost for a gaggle of tourists.

WIDMER: I was reading an interview with a poltergeist expert and he was talking about the geography of it. You have your different genres—there’s your Wild West cowboy ghosts, your New England witch ghosts—and he was just saying that Louisiana, New Orleans specifically, is the most dense ghost region in the nation. The combination of the voodoo Haitian influence on top of the horrific ways in which all the slaves were treated there, and the orphanages and the Catholic iconography, you grind all that up and it creates a weird ghost stew.

COMINGORE: I also wanted to ask you about the music scene down there. Specifically, I’m fascinated with the whole bounce culture thing.

WIDMER: It is a fascinating thing. You probably know more about it than I do.

JOYNER: I don’t think I know more about it than most people, really.

WIDMER: Correct me if I’m wrong, but I think it was called “sissy bounce” before it was this massive national trend. I think I first heard the term in 2007 or 2008 and it was referring to a certain transgender element—guys that dressed up like women and certain musical touchstones that are true to all bounce music, like the “ca ca ca…”

JOYNER: [sings] “I want that gin in ma system.”

WIDMER: Yeah. And Big Freedia and Katey Red are the big names. I mean, Big Freedia is huge now.

JOYNER: I definitely saw my first bounce show by accident. I was standing there, mouth agape, wondering what was going on.

COMINGORE: Were there other band names you guys tossed around before you chose Generationals?

WIDMER: Yes. Porpoise Police.

COMINGORE: Did you say Porpoise or Corpus?

JOYNER: Porpoise. Do you think we picked the right one? [laughs]

COMINGORE: Do you have a favorite distinctly Southern food item?

JOYNER: Sometimes I have a fried chicken “problem.” I’ve cut down a lot. But I realize it’s one of those things that may haunt me for my entire life. Is that an unfair one? I mean, everyone has fried chicken.

WIDMER: I like grits with jelly. But grits are everywhere.

JOYNER: Shrimp and grits, love it. But that’s kind of a Carolina thing versus Louisiana. The fact that we’re not saying state-specific stuff might get us in trouble.

WIDMER: I’ve got one. There’s a distinctly New Orleans-style presentation of fish called “almondine”—you get trout almondine, catfish almondine. It’s a famous dish that’s really good.

COMINGORE: If you could magically learn one instrument overnight, what would it be?

JOYNER: Piano? Piano properly.

WIDMER: Yeah. Ted probably knows more than I do, but I would love to be incredible at it, just for like—

JOYNER: Parties. The shock value of waltzing into a room and having someone go, “Oh Ted, play a song.” And then you go, “No, no, no, no.” And then finally they get you up there and you just rip it up and everyone is like, “Oh jeez, he’s amazing!”

WIDMER: Like Jerry Lee Lewis it.

JOYNER: But you have to be fighting it the whole time. Like, “Oh man, I’m so rusty,” and then you just race up the keys.

COMINGORE: Do you guys have any hidden talents?

WIDMER: I can juggle.

JOYNER: [whistles]

COMINGORE: Birdcalls?

JOYNER: Cricket sounds, for when someone makes a bad joke and no one laughs.

WIDMER: I’m pretty good at trivia. I don’t know if that’s a talent, but I keep up with lots of interviews, shows, podcasts. Deep cuts, I pay attention to deep cuts.

JOYNER: Mine is just the cricket sound.

COMINGORE: Do you tend to get anxious around album release time?

JOYNER: I guess so? But it’s concurrent with this excitement about getting out on the road.

WIDMER: And there’s usually so much prep work that goes into the tour that it totally decentralizes any anxiety about the release.

COMINGORE: Do you have any hopes for what you want people to take away from Alix?

WIDMER: I guess I just hope that people take it for what it’s trying to be and not anything else.

JOYNER: I think the more you put out the more context people have, as opposed to starting from zero. So, hopefully, there’s an ever-growing amount of people who are following along. Those are the people lately that I guess I’m most interested in, because I feel like we started a conversation there. When you start from zero, that’s anybody’s game.

COMINGORE: Are you guys still excited at the prospect of going on tour?

WIDMER: Yeah. I feel like the goal for this tour and the last few tours has been to make the previous tour look like garbage.

JOYNER: And I think we’ve accomplished that to some extent.

WIDMER: If I was at my show from two years ago I would not be impressed.

JOYNER: We’re still putting a lot of pressure on ourselves to make it way better, and that makes it fun. I still feel like our best shows are ahead of us, and that’s exciting.

ALIX IS OUT TOMORROW ON POLYVINYL RECORDS. FOR MORE ON GENERATIONALS, PLEASE VISIT THE BAND’S WEBSITE.